Up Against the Bulkhead: Difference between revisions

(fixed audio link) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

''by Stephen Rees and Peter Wiley, excerpted from their photo essay "Up Against the Bulkhead,'' in the anthology "Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-78" (City Lights Foundation: 2011), edited by Chris Carlsson.'' | ''by Stephen Rees and Peter Wiley, excerpted from their photo essay "Up Against the Bulkhead,'' in the anthology "Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-78" (City Lights Foundation: 2011), edited by Chris Carlsson.'' | ||

[[Image:Ten Years small 87286100958430M.gif]] Find the book at [ | [[Image:Ten Years small 87286100958430M.gif]] Find the book at [https://citylights.com/foundation-books/10-years-that-shook-the-city-sf-68-78/ City Lights]! | ||

Revision as of 21:54, 23 November 2021

"I was there..."

Listen to an excerpt from "Up Against the Bulkhead" read by co-author Peter Wiley:

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/8TenYears--upAgainstTheBulkhead" width="500" height="30" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

by mp3.

![]()

Previous stop: Earth-shattering and heaven-startling event

Next Stop #9: Ntozake Shange in the Mission

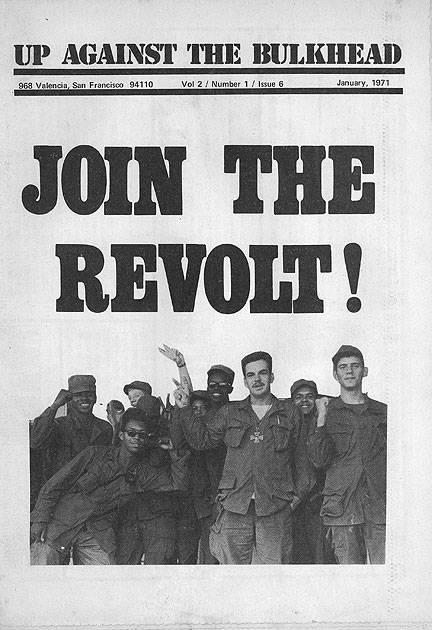

In 1971 a handful of sailors from the USS Coral Sea, an aircraft carrier based at the Alameda Naval Air Station, showed up at the Leviathan office at 968 Valencia Street, which also served as a maildrop for The Bulkhead. The Navy’s carrier strike force, including ships that sailed from San Diego and Alameda to their duty station in the South China Sea, was subjecting tiny Vietnam to an aerial bombardment more intense than the bombing of Europe during World War II. Ultimately, a million citizens, many of them the victims of aerial bombardment, would die in Vietnam and neighboring Cambodia and Laos. The sailors had read The Bulkhead, specifically stories about about anti-war organizing on aircraft carriers. They were ready for action and were particularly interested in meeting David Harris, the Stanford draft resister who was working with civilians and anti-war sailors on the carrier Constellation, which was homeported in San Diego.

Demonstrators support Coral Sea sailors attempting to stop their ship from sailing to Vietnam.

Photo: Stephen Rees

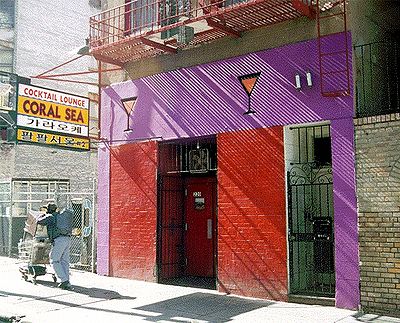

We were pleased, but not surprised that these sailors had tracked us down. On any given night, people from The Bulkhead collective and the Pacific Counseling Service (PCS) could be found at the San Francisco Airport or on Market Street where GIs drifted between the seedy bars in the Tenderloin, including one called The Coral Sea, and the United Service Organization’s drop-in center nearby on Market St.

The Coral Sea bar at 220 Turk Street, seen here in the late 1990s.

Photo: Dimitri La Marea

We were handing out Bulkheads and information about the legal support offered by the PCS to GIs. Invariably the GIs were friendly and receptive. The Coral Sea sailors were a colorful lot, veritable hippies in uniform. (As a concession to growing dissension among sailors, Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, who became Chief of Naval Operations in 1970, issued his famous “Z grams,” permitting sailors to wear beards, mustaches, sideburns, and longish hair as long as they were well-groomed.) The Coral Sea brothers considered themselves freaks and were more than eager not only to investigate ways to oppose the war, but also ways to sample the offerings of countercultural hedonism. In time some of them would join the network of interlocking political households that was spreading beyond Bernal Heights.

Veterans Against the War march on Market Street in San Francisco.

Photo: Stephen Rees

At the time we had no idea what impact the GI movement was having on military thinking. We did some of our research for The Bulkhead at the Presidio Base Library, no questions asked (not even a stare). In the summer of 1971, we came across an article by former Marine Colonel Robert Heinl in the Armed Forces Journal. “The morale, discipline and battle-worthiness of the US armed forces,” Heinl wrote, “are, with a few salient exceptions, lower and worse than at any time in the history of the United States.” Up until then it seemed that no matter how large and militant anti-war demonstrations became, no matter how many campus buildings were seized and draft boards were attacked or burned, the war machine rolled on like some demon Moloch up to its armpits in blood and body parts. With GIs, apparently, we were getting results.

Encouraged, we pushed on. We put together a sophisticated distribution system for The Bulkhead that reached as far as Vietnam via packages mailed to GIs who used Armed Forces Post Office addresses in San Francisco. We also received help from stewardesses who worked the chartered commercial aircraft that flew troops out of Travis Air Force base in Vacaville to Tan Son Hut near Saigon. We supplemented copies of The Bulkhead with packets of articles about Vietnam and Southeast Asia gleaned from the straight press. We pulled the articles from the files of the Bay Area Research Project, which was organized by Berkeley Professor Franz Schurmann and journalist Orville Schell when they founded Pacific News Service in 1969. From the Vietnamese we received black buttons depicting an Armalite rifle with its bayonet stuck in the ground. Inscribed on it in Vietnamese were words that were a signal to Vietnamese soldiers not to shoot at the US troops wearing the buttons. We sent them along to our contacts in Vietnam.

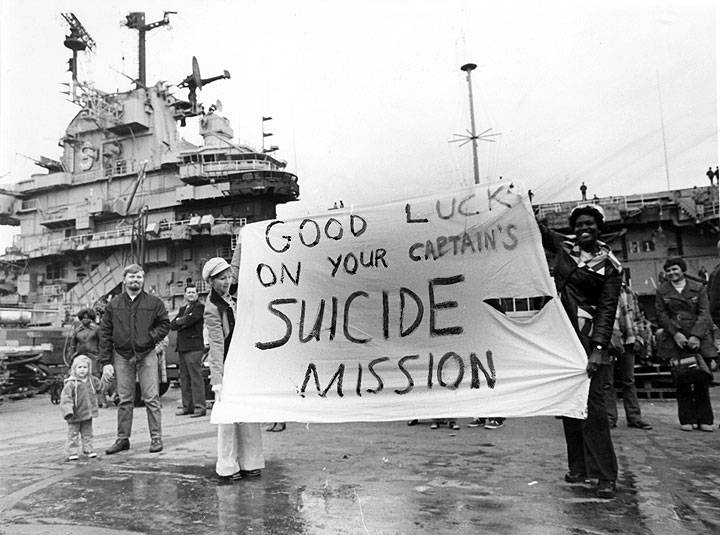

Vicki Kelly and Rose Hills display their banner in front of the USS Coral Sea, 1974.

Photo: Stephen Rees

It was only after the war ended in 1975, that we began to understand the truly vast nature of the GI movement and the impact this militancy would have on whether to remain in Vietnam or not. The immediate impact in the Bay Area was dramatic: in the first three months of 1970 during which The Bulkhead and PCS began an extensive schedule of leafleting, 1,200 soldiers scheduled to ship out through local facilities delayed their departure by seeking conscientious objector status. The Pentagon quickly retaliated, instructing West Coast base commanders to stop accepting applications for CO status. Still, the GI movement rolled on. In 1971 Heinl estimated that there were 144 underground newspapers published on or near US military bases. These papers, which ranged from broadsheets on newsprint to mimeographed newsletters on standard 8x11 paper, provided The Bulkhead with news from around the movement while we, acting as a kind of news service along with the GI News Service, provided them with content. In 1972 the Department of Defense estimated that there were 245 GI newspapers. In his carefully researched book, David Cortright lists 259 publications. The Department of the Army reported that the number of “acts of insubordination, mutiny and willful disobedience” increased from 252 in 1968 to 382 in 1970 and then to 450 in 1971, according to the New York Times. Before the war ended there were ten reported “major incidents” of mutiny within Vietnam itself.

by Stephen Rees and Peter Wiley, excerpted from their photo essay "Up Against the Bulkhead, in the anthology "Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-78" (City Lights Foundation: 2011), edited by Chris Carlsson.

Find the book at City Lights!

Find the book at City Lights!