A VISIT TO THE BAY AREA IN 1835: Difference between revisions

fixed navigation for new page |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

''by Richard Henry Dana'' | ''by Richard Henry Dana'' | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" | '''An excerpt from Richard Henry Dana’s work “Two Years Before The Mast.” in which the author describes his first experiences entering San Francisco bay as a sailor on the Boston trading rig Alert. Dana’s retelling of he and his crew’s arrival includes arriving with hopes to trade hide and tallow up and down the coast with the natives as well as his experiences and opinions regarding traders from “Russian America.” Dana’s account is a useful tool in grasping the ideas regarding the physical landscape of the area at the time as well as Northern California’s early potential as a center for trade and migration. ''' | |||

|} | |||

[[Image:transit1$merchant-ship-photo.jpg]] | [[Image:transit1$merchant-ship-photo.jpg]] | ||

Revision as of 12:12, 19 September 2016

"I was there..."

by Richard Henry Dana

| An excerpt from Richard Henry Dana’s work “Two Years Before The Mast.” in which the author describes his first experiences entering San Francisco bay as a sailor on the Boston trading rig Alert. Dana’s retelling of he and his crew’s arrival includes arriving with hopes to trade hide and tallow up and down the coast with the natives as well as his experiences and opinions regarding traders from “Russian America.” Dana’s account is a useful tool in grasping the ideas regarding the physical landscape of the area at the time as well as Northern California’s early potential as a center for trade and migration. |

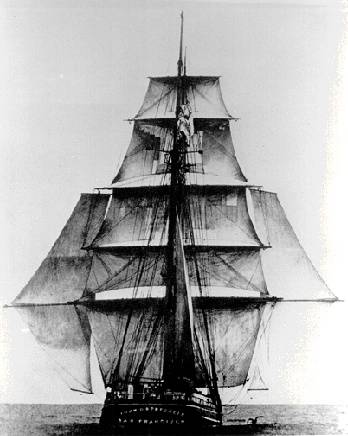

19th century merchant ship under sail.

Photo: San Francisco Maritime Museum

Richard Henry Dana (1815-1882) sailed into San Francisco Bay in December 1835. He was a sailor aboard the brig Alert which carried hide and tallow trade along the California Coast. The trading of animal hides and tallow (animal fat used to make candles, soap and lubricant) between the Indians and East Coast merchants was the dominant commercial activity along the California Coast from the 1820s to the 1840s. The Alert anchored in the bay for a three week period to gather supplies and to trade in hides as the missions of "San Jose, Santa Clara, and others, situated on large creeks or rivers which run into the bay, do a greater business in hides than any in California."

After returning to his hometown, Boston, Dana wrote about his travel experiences in "Two Years Before the Mast," a book which encountered great success and is still in print today. In this excerpt, Dana remembers meeting the crew of a Russian vessel, which came down to San Francisco Bay from Russian California to gather supplies of tallow and grain. Among other things, he also recalls spending two long, rainy nights in an open boat gathering wood on an island he and his mates called Wood Island, an island known today as Angel Island. The opening statement that Sir Francis Drake discovered the bay is erroneous and can be traced back to the common belief that San Francisco's Bay could be entered through Drakes Bay (the bay west of Point Reyes, discovered by Drake in 1579). The Bay of San Francisco was actually first sighted by Europeans during a land expedition led by Spanish explorer Gaspar de Portola in 1769.

This excerpt is valuable for its description of the natural landscape and the commercial activity of the San Francisco Bay Area at that period in time. Particularly noteworthy are also Dana's prophetic comments regarding the future of the region as the great metropolis of California. In Dana's 1835 assessment: "If California ever becomes a prosperous country, this bay will be the centre of its prosperity."

Excerpt

Friday, December 4th, after a passage of twenty days, we arrived at the mouth of the bay of San Francisco.

Our place of destination had been Monterey, but as we were to the northward of it when the wind hauled a-head, we made a fair wind for San Francisco. This large bay, which lies in latitude 37 deg. 58', was discovered by Sir Francis Drake, and by him represented to be (as indeed it is) a magnificent bay, containing several good harbors, great depth of water, and surrounded by a fertile and finely wooded country. About thirty miles from the mouth of the bay, and on the south-east side, is a high point, upon which the presidio is built. Behind this, is the harbor in which trading vessels anchor, and near it, the mission of San Francisco, and a newly begun settlement, mostly of Yankee Californians, called Yerba Buena, which promises well.

Here, at anchor, and the only vessel, was a brig under Russian colors, from Asitka, in Russian America, which had come down to winter, and to take in a supply of tallow and grain, great quantities of which latter article are raised in the missions at the head of the bay. The second day after our arrival, we went on board the brig, it being Sunday, as a matter of curiosity; and there was enough there to gratify it. Though no larger than the Pilgrim, she had five or six officers, and a crew of between twenty and thirty; and such a stupid and greasy-looking set, I certainly never saw before. Although it was quite comfortable weather, and we had nothing on but straw hats, shirts, and duck trowsers, and were barefooted, they had, every man of them, doublesoled boots, coming up to the knees, and well greased; thick woolen trowsers, frocks, waistcoats, pea-jackets, woolen caps, and everything in true Nova Zembla rig; and in the warmest days they made no change. The clothing of one of these men would weigh nearly as much as that of half our crew. They had brutish faces, looked like the antipodes of sailors, and apparently dealt in nothing but grease. They lived upon grease; eat it, drank it, slept in the midst of it, and their clothes were covered with it. To a Russian, grease is the greatest luxury. They looked with greedy eyes upon the tallow-bags as they were taken into the vessel, and, no doubt, would have eaten one up whole, had not the officer kept watch over it. The grease seemed actually coming through their pores, and out in their hair, and on their faces. It seems as if it were this saturation which makes them stand cold and rain so well. If they were to go into a warm climate, they would all die of the scurvy.

The vessel was no better than the crew. Everything was in the oldest and most inconvenient fashion possible; running trusses on the yards, and large hawser cables, coiled all over the decks, and served and parcelled in all directions. The topmasts, top-gallant masts and studding-sail booms were nearly black for want of scraping, and the decks would have turned the stomach of a man-of-war's-man. The galley was down in the forecastle; and there the crew lived, in the midst of the steam and grease of the cooking, in a place as hot as an oven, and as dirty as a piggy. Five minutes in the forecastle was enough for us, and we were glad to get into the open air. We made some trade with them, buying Indian curiosities, of which they had a great number; such as bead-work, feathers of birds, fur moccasins, etc. I purchased a large robe, made of the skins of some animals, dried and sewed nicely together, and covered all over on the outside with thick downy feathers, taken from the breasts of various birds, and arranged with their different colors, so as to make a brilliant show.

A few days after our arrival, the rainy season set in, and, for three weeks, it rained almost every hour, without cessation. This was bad for our trade, for the collecting of hides is managed differently in this port from what it is in any other on the coast. The mission of San Francisco near the anchorage, has no trade at all, but those of San Jose, Santa Clara, and others, situated on large creeks or rivers which run into the bay, and distant between fifteen and forty miles from the anchorage, do a greater business in hides than any in California. Large boats, manned by Indians, and capable of carrying nearly a thousand hides apiece, are attached to the missions, and sent down to the vessels with hides, to bring away goods in return. Some of the crews of the vessels are obliged to go and come in the boats, to look out for the hides and goods. These are favorite expeditions with the sailors, in fine weather; but now to be gone three or four days, in open boats, in constant rain, without any shelter, and with cold food, was hard service. Two of our men went up to Santa Clara in one of these boats, and were gone three days, during all which time they had a constant rain, and did not sleep a wink, but passed three long nights, walking fore and aft the boat, in the open air. When they got on board, they were completely exhausted, and took a watch below of twelve hours. All the hides, too, that came down in the boats, were soaked with water, and unfit to put below, so that we were obliged to trice them up to dry, in the intervals of sunshine or wind, upon all parts of the vessel. We got up tricing-lines from the jib-boom-end to each arm of the fore yard, and thence to the main and cross-jack yard-arms. Between the tops, too, and the mast-heads, from the fore to the main swifters, and thence to the mizen rigging, and in all directions athwartships, tricing-lines were run, and strung with hides. The head stays and guys, and the spritsail-yard, were lined, and, having still more, we got out the swinging booms, and strung them and the forward and after guys, with hides. The rail, fore and aft, the windlass, capstan, the sides of the ship, and every vacant place on deck, were covered with wet hides, on the least sign of an interval for drying. Our ship was nothing but a mass of hides, from the cat-harpins to the water's edge, and from the jib-boom-end to the taffrail.

One cold, rainy evening, about eight o'clock, I received orders to get ready to start for San Jose at four the next morning, in one of these Indian boats, with four days' provisions. I got my oil-cloth clothes, south-wester, and thick boots all ready, and turned into my hammock early, determined to get some sleep in advance, as the boat was to be alongside before daybreak. I slept on till all hands were called in the morning; for, fortunately for me, the Indians, intentionally, or from mistaking their orders, had gone off alone in the night, and were far out of sight. Thus I escaped three or four days of very uncomfortable service.

Four of our men, a few days afterwards, went up in one of the quarter-boats to Santa Clara, to carry the agent, and remained out all night in a drenching rain, in the small boat, where there was not room for them to turn round; the agent having gone up to the mission and left the men to their fate, making no provision for their accommodation, and not even sending them anything to eat. After this, they had to pull thirty miles, and when they got on board, were so stiff that they could not come up the gangway ladder. This filled up the measure of the agent's unpopularity, and never after this could he get anything done by any of the crew; and many a delay and vexation, and many a good ducking in the surf, did he get to pay up old scores, or "square the yards with the bloody quill-driver."

--Richard Henry Dana'