Shanghaiing: Difference between revisions

Texteradmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

(added Satty collage) |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

Of course, their whiskey was drugged. Bailey says that he and his pal woke the next day to a kick in the stomach and orders to heave hard, and they labored at sea for months. | Of course, their whiskey was drugged. Bailey says that he and his pal woke the next day to a kick in the stomach and orders to heave hard, and they labored at sea for months. | ||

[[Image:Satty-p-98-Shanghai-City.jpg]] | |||

''Collage depicting shanghaiing by [[Satty and the "North Beach U-Boat"|Satty]], from "Visions of Frisco" edited by Walter Medeiros, Regent Press 2007'' | |||

The history of the waterfront is buried under an encrustation of such local lore, and it demonstrates the power of anecdotes to perpetuate, and trivialize, a given version of history. Go look at the sign outside Shanghai Kelly's bar at the corner of Broadway and Polk Street, and you'll see the result of the trivialization process: a goopy caricature of a paunchy man with a sort of truncheon (maybe a blackjack, or maybe a rubber bath toy) who looks as if he might spank you. | The history of the waterfront is buried under an encrustation of such local lore, and it demonstrates the power of anecdotes to perpetuate, and trivialize, a given version of history. Go look at the sign outside Shanghai Kelly's bar at the corner of Broadway and Polk Street, and you'll see the result of the trivialization process: a goopy caricature of a paunchy man with a sort of truncheon (maybe a blackjack, or maybe a rubber bath toy) who looks as if he might spank you. | ||

Revision as of 00:13, 20 December 2011

Historical Essay

by Georgia Smith

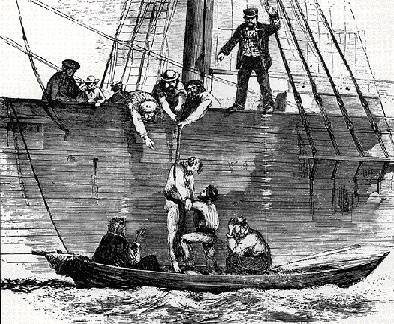

Shanghaied sailors being lifted onto a ship.

Image: Bill Pickelhaupt, Flyblister Press

One afternoon in the 1890s, Hiram Bailey and his friend Ben (neither one a sailor) went into a dive down on the waterfront:

“Over our drinks, I conveyed to Ben casually--for Ben knew nothing of sea-life, and I but a little more--that it was common talk about the harbour that the Benares had put to sea with two clergymen, three bar-tenders, four agricultural labourers -- all shanghaied. . .

‘But what is the meaning of shanghaied?’ inquired my companion, looking puzzled.

I was about to explain in detail when Ben turned and ordered from Calico Jim a small bottle of whiskey. ‘A little of it does your nerves good,’ he added to me. No whisky like Old Country whisky. I manfully agreed, as I closely examined the sealing of the cork. ‘New untouched bottle, no dope in this,’ I remarked to Ben intelligently and with the air of knowing a thing or two. I was eighteen.

The man in pulling the cork and joining in our conversation butted the matter of shanghaiing clean out of my mind. Calico Jim, who now sat at the same table with us, brought his glass and very suavely invited himself to join in our conversation. He gave us indeed from a special bottle a good swig -- ‘The best’ he said, complimentarily.

Though it is a long time ago now, I can still remember a strange but pleasant sort of drowsy feeling stealing over me whilst taking that swig and there is still silhouetted upon my mind that scoundrel's evil face intently watching me. It never occurred to me why.” (Bailey 1934)

Of course, their whiskey was drugged. Bailey says that he and his pal woke the next day to a kick in the stomach and orders to heave hard, and they labored at sea for months.

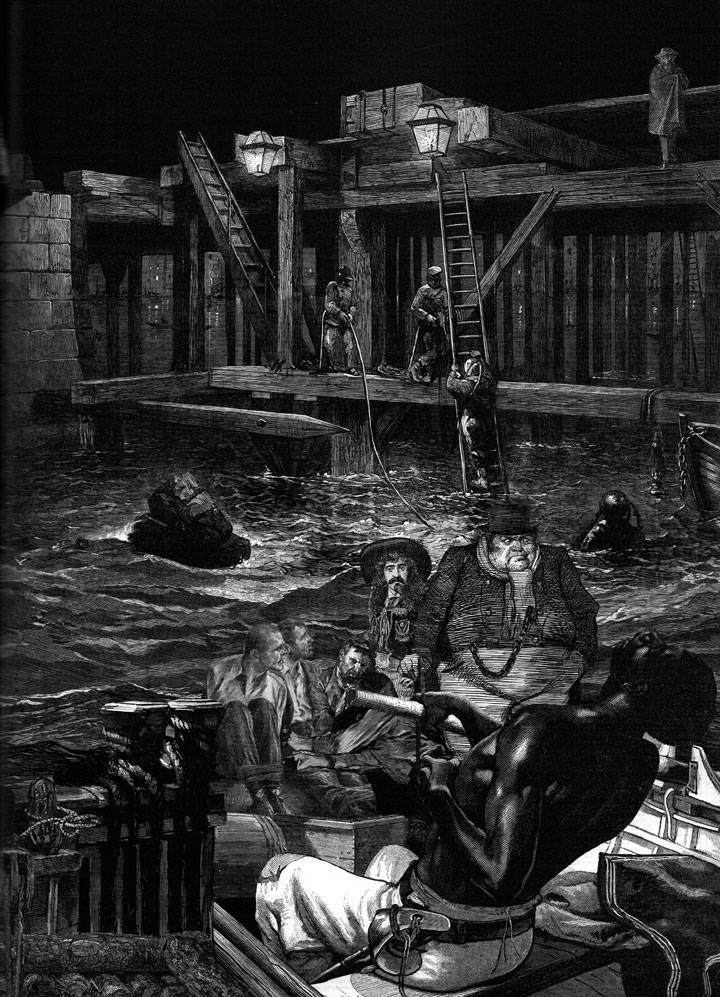

Collage depicting shanghaiing by Satty, from "Visions of Frisco" edited by Walter Medeiros, Regent Press 2007

The history of the waterfront is buried under an encrustation of such local lore, and it demonstrates the power of anecdotes to perpetuate, and trivialize, a given version of history. Go look at the sign outside Shanghai Kelly's bar at the corner of Broadway and Polk Street, and you'll see the result of the trivialization process: a goopy caricature of a paunchy man with a sort of truncheon (maybe a blackjack, or maybe a rubber bath toy) who looks as if he might spank you.

There was a real James “Shanghai” Kelly, who kept a boarding house (variously reported to be on Pacific or Broadway) and who later ran the Boston House at the corner of Davis and Chambers streets. He's highly mythologized: they say his saloon had three trapdoors through which unconscious sailors--whether drugged or knocked on the head--were dumped and then spirited away to waiting ships. They say that Chinatown cigar makers made up special brands for him, laced with opium, to give to unsuspecting Sailor Jack. They say he shipped out corpses and even, once, a cigar-store Indian. (A competitor, Nikko the Lapp, who was a runner for the shanghaiier Miss Piggott, supposedly specialized in sewing rats into a dead man's clothing, then dumping the corpse in a bag and delivering it to a ship as a dead-drunk sailor; the rats made it twitch in a reasonably lifelike manner. So they say.)

They say Shanghai Kelly was himself shanghaiied by fellow-crimp Johnny “Shanghai Chicken” Devine, and that Kelly was shot down in Peru, just as Calico Jim was supposedly shot down in Callao, or, in some versions, Valparaiso.

The most elaborate Shanghai Kelly anecdote runs like this: three ships lay anchored in the Bay waiting for crews, and Kelly decided to make a pile of money by getting crews for all three. He chartered a paddle-wheeler to throw a birthday bash for himself, and issued a blanket invitation along the waterfront. Ninety people packed the steamer. Then:

“Kelly, the story went, first ordered the boat south toward Alviso. But as the merrymakers drained the barrels of booze and grew more intoxicated, the steamer turned around and headed out the Golden Gate into the Pacific Ocean. By that time, the partygoers were in a stupor, drugged by the liquors knock-out potions.

“Kelly hoisted the drugged parties over the side onto each of the three waiting ships. On his way back to town--what extraordinary luck!

“By coincidence, a ship, the Yankee Blade, had wrecked shortly before and it was believed Kelly picked up some of the shipwrecked survivors. In the excitement when the boat returned to dock, no one questioned what had become of his original revelers.” (Pickelhaupt 1996)

The above has been carefully discredited by Bill Pickelhaupt in his thoroughly researched book, Shanghaied in San Francisco. The ships involved were apparently not in, or even near, San Francisco at the time the events were supposed to have taken place; in fact, Pickelhaupt finds that the Yankee Blade wreck was 300 miles south, off Point Conception.

But shanghaiing--drugging a man and then kidnapping him to work on a ship--was real. It was commonplace. A ninenteenth-century sailor's experience of San Francisco generally involved the process of being kicked back out to sea again.

There were good reasons for this: if ships needed crews they would pay so-called blood money for the necessary men. Certain voyages were difficult to staff even when men were available: for example, the run from San Francisco to Shanghai, China, was unloved because it was difficult to get a return trip; usually you had to ship all the way around the world to make it home to San Francisco, which could easily take more than a year. It was this phenomenon that gave birth to the nickname “shanghaiier” to denote the crimps of San Francisco.

Blood money (which, though outlawed partway through the century, continued to be paid when necessary) was just part of the crimps' inducement. Sailors were allowed two months advance on their wages before a trip, to pay off debts and to outfit themselves for the trip. The sailor wasn't given the money: he might abscond. His creditors got it directly from the ship. This was the taproot of the shanghaiing system. According to a former seaman:

“When sailors were scarce, the boarding-house master who supplied the ships with crews had recourse to the shanghaiing of any man who would sit and drink with him. Friends of the boarding-house master signed the ship's articles for the proposed victim, giving the man's name, if they knew it; but sometimes a man would wake up at sea and find himself with a new name. After the ship had sailed the boarding-house master would collect the advance made out in his favour for board and lodgings and clothing supplied. The game was very profitable. . . .” (Farmer n.d.)

Sometimes the captain got a kick-back from the crimps:

[T]he Pitcairn's cargo was discharged, her skipper secured a new charter, and two days before sailing he and the shipping-master said something to each other over a table in the Fair Winds saloon, where the shipping-master had his little private room. Here it was that he invited skippers to help him solve simple mathematical problems--easy, they consisted of subtracting something from something and dividing by two.” (Sonnichsen 1903)

A sailors wages could thus be shared by a fair number of people, excluding only the sailor himself.

The 1897 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Robertson v. Baldwin lays bare the foundations on which such a system could exist. The court excluded civilian sailors on merchant ships from the 13th Amendment's protection against involuntary servitude with the extraordinary rationale that Seamen are . . . deficient in that full and intelligent responsibility for their acts that is accredited to ordinary adults, and therefore must be protected from themselves in the same sense in which minors and wards are entitled to the protection of their parents and guardians. (Quoted in Pickelhaupt 1996)

The Rev. James Fell founded the Seamen's Institute, a social center and safe haven for sailors in San Francisco during the 1890s. In a report to the British Government on the situation of merchant seamen in San Francisco, Fell rails against the institutionalized abuse of sailors. When he tells an anecdote, he's convincing partly because he's so prissily cautious in his presentation. It's too bad he never named names:

One afternoon the large ship came into the bay, after being at sea for months. The crew, of course, knew nothing about the scarcity of sailors on shore, and the ships waiting in the bay for men. The crimps, as usual, boarded the ship, and extraordinary tales of the lucrative jobs on shore just waiting for men to fill them were told, the usual drinks flew round, and some of the men went with them. . . . The next morning, at 10 a.m., the writer was talking to the second officer of the ship which was waiting for men in the bay, and he remarked, “We've got our men; they're off the _______ , which came in yesterday afternoon.” He was asked, “Are they drunk?” and the answer was, “Yes, violent; we've got em locked up.” Then he was asked, “What time did they come on board?” and he said “Nine o'clock.”

Now, the British Consul's office where men sign articles on British ships closes at 3 p.m. and opens at 10 a.m. Even if these men did get ashore by 2.30 p.m., which was impossible, it is ridiculous to think that, fresh from a six months voyage, they would go within half an hour of landing and sign articles on another long-voyage ship going a four or five months trip. We all know that, easily taken in as sailors are, they would never do that. They were on board the by 9 a.m. in a drunken state, and the Consul's office did not open till 10 a.m. Who, then, signed the articles, and their two months advance away? On this and kindred subjects being mentioned to a shipping authority, his reply was that it was best not to mention these things, as they had to be done in busy times. (Fell 1899)

--from "About That Blood in the Scuppers" in Reclaiming San Francisco: History Politics and Culture, a City Lights Anthology, 1998

File:Labor1$33-pacific-st-.jpg

No. 33 Pacific between Drumm and Davis streets was once the home of Shanghai Kelly, whose victims were drugged, blackjacked and dropped through trap doors into a boat.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Book reference: Shanghaiing in San Francisco