Mission Miracle Mile: Difference between revisions

Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>"I was there..."</font></font> </font>''' ''by Robert Anderson, 2025'' <big>'''The Great Good Place Then and Now'''</big> :::''To the memory of my parents'' 792px '''22nd and Mission Streets, 1950s.''' ''Photo: provenance unknown'' The Miracle Mile began at Army and Mission, at the big Sears Store, and ended at 16th and Mission, at Lachman Brothers Furniture Store, w..." |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 13:19, 7 November 2025

"I was there..."

by Robert Anderson, 2025

The Great Good Place Then and Now

- To the memory of my parents

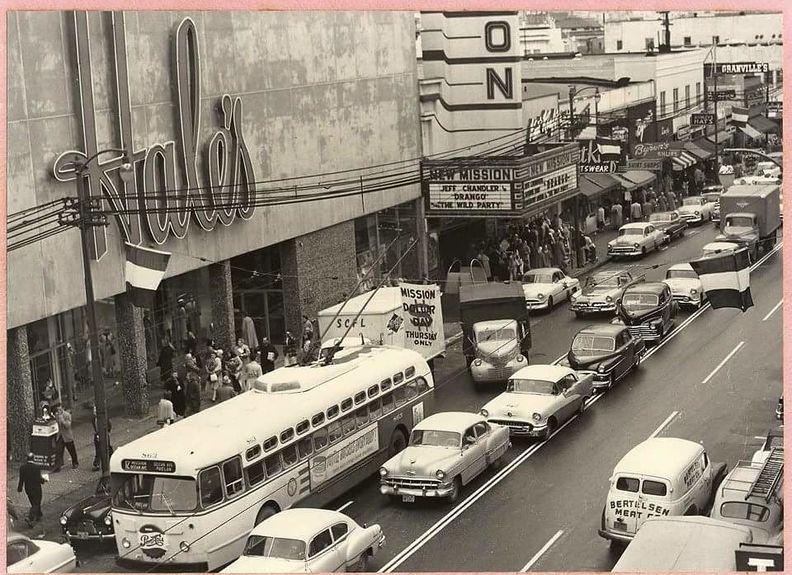

22nd and Mission Streets, 1950s.

Photo: provenance unknown

The Miracle Mile began at Army and Mission, at the big Sears Store, and ended at 16th and Mission, at Lachman Brothers Furniture Store, where my father worked as a warehouseman. Rarely would my mother get past the New Mission Theater though. Just in time for the matinee. In fact I don’t recall a time when we visited my father at work, who got a daily lift home after a beer or two at the Old Corner, on 17th and Capp.

Women sales clerks picketing Sears at Mission and Army in the 1940s.

Photo: Labor Archives and Research Center, SFSU

Sears picket line c. 1948.

Photo: Labor Archives and Research Center, SFSU

My mother loved a long walk, any excuse would do, need shoes, so off we went, down Fairmount to 30th and Mission, hence to Army and first-stop the Sears, passing the short-lived Lyceum Theater, which packed them in for a three feature Saturday matinee, only a dime for instant bedlam. A sugar high for a thousand shrill kids. Once past McBlaine’s Toy Store (lay-away for Christmas) Mission Street became a horn-of-plenty, a bevy of stores and markets and movie palaces and restaurants catering to those of us living in the fable that was San Francisco in the halcyon years (1945-63).

San Francisco then was a blue-collar paradise and a blue blood bell jar. The bluebloods shopped at Union Square—the City Of Paris the acme of the good life in Pacific Heights—while the Avenues-bound middle-class shopped on Market Street—The Emporium stands-out. But the Mission Miracle Mile belonged to blue-collar San Franciscans. It was our street of mercantile record, our boulevard of boyhood passage, our boulevard of modest dreams.

You could find everything you ever needed—shoes, school uniforms, funeral suits and wedding dresses, home furnishings, trophies, eyeglasses, jewelry, gypsy readings, a banana split (my mother’s favorite), an afternoon spent watching The Vikings on the big screen in the spotless New Mission Theater, where my best friend’s father worked as a janitor. You could also find everything—sporting goods much in demand—that equipped you for the turnstile rush of a great sports town, the Dons, the Seals, the 49ers, the Giants.

The miracle of deliverance that was V-J Day gave new life to the Street, and the surge of postwar prosperity brought a baby boom that crowded Mission Street with pent-up demand. Let the good times roll. Baby furniture and a new couch and a dining room table and a host of marvels that made housekeeping easier. Miraculous inventions. Washing machines and refrigerators and gas stoves and television sets. For fifteen years the furniture stores—Lachman Brothers on 16th and Redlicks (17 Reasons Why) on 17th —couldn’t keep up with the demand. My father worked hard shipping and receiving, off the truck to the showroom, on the truck for home delivery.

Every month, thanks to that MMM paycheck, my mother and I would go to the Bank Of America branch in Glen Park and pay the mortgage on the small house on the 200 block of Whitney. Those were flush times, and everybody I knew was in the same socioeconomic boat. Egalitarian folkways made the Street a communal property. Everybody flocked to Mission Street; everybody flocked to Seal’s Stadium; everybody flocked to the New Mission Market; everybody flocked to the Grand or Tower or El Capitan or New Mission Theater; everybody flocked to this realization of the great good place.

Omnes Habitare in Civitati Sancti Francisci Volunt. The Civitati came with a civil religion and a dress code. You didn’t go downtown unless you wore your Sunday best, and you didn’t hang out on Mission Street venerating the Miracle unless you could translate that latin truism in your sleep. Everyone wanted to be in your shoes. The Mediterranean city-state hard by the fog-bound Pacific wore its nimbus well, and the sacred and profane were entwined, fused really (the dome of Saint Peters atop City Hall) by a joint celebration of good fortune.

Nowhere was that truer than in the Mission, the banana belt, where the sun burned off the fog—voila, a California summer day after all—and little Central America basked in the good times afforded by Mission High School and Mission Dolores Park and Mission Dolores Basilica and Mission Pool and the Mission Branch of the SF Public Library.

Since my parents were born and raised in the Mission, and met at Cogswell Poly off Army Street, I felt at home there too, and fairly reveled in the native ground. The Mission Branch and Seals Stadium and the New Mission Theater and Mission Dolores Park were frequent haunts of my boyhood.

Cogswell Polytechnical College, 3000 Folsom Street at 26th Street, Bernal Heights visible in background, looking south, during 1984 demolition.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp32.3396

For 50 cents you sat in the right-field bleachers and bantered with No. 24 between innings. For a quarter you sat spellbound at the wonders of Cinemascope in the El Capitan, and you sat in terror at The Thing in the small confines of the Grand. The august high-arched branch library was imposing, serious readers only, and the glee of tumbling down the step-down slope of Dolores Park a lark of a feral boyhood made possible by the Mission District at peak comity. Peak veneration.

Willie Mays playing centerfield in Seals Stadium, c. 1959.

Photo: Provenance unknown

A blue-collar paradise by definition is one that exists only as a fever dream, a fugitive past, a post-mortem. By the early 60s the MMM had run out of miracles. Out of congested foot traffic. Out of spendthrift purchasing power. Prosperity and the lure of the good life in the blue-collar suburbs saw the Valleys (Castro, Cole, Eureka, Noe) empty out and the diaspora, to the fog belt of San Bruno and Westlake saliently, eat away at the vitals of the Civitati. The Mission Miracle Mile was spent. Done. A Fire Sale.

The seedy, the transient, the down on their luck became the watchword, watch your purse, as the great furniture stores struggled and the movie theaters went dark and Seals Stadium was demolished and BART tore up the street and the influx from Central America and Mexico gave the Mission a pronounced Spanish inflection. Introducing class bondage in a number of patois. Introducing day laborers on Army. Introducing gangs. Introducing the social entropy of paradise lost.

My father stuck it out at Lachman’s—the Follies burlesque palace next door kept Sixteenth Street from hitting the skids entirely. Six months after my father retired at 62 he was hit with a massive stroke, and by some miracle—the doctors were amazed—survived only because he had done hard labor. The MMM had saved his life. He lived another twenty years.

It will take a miracle to restore 16th and Mission to its former glory. Now a SFPD encampment pending the return of civic engagement on the heroic scale. An iron will with staying power. The Mission in particular could use a revival of the civic religion. Once upon a time all right.

Gone was the Miracle but the miracle of The Mission soldiers on. Still the best weather in The City. Still the best place to secure a foothold in The City. Still the best place to combat gentrification. Still the best place to see The City whole, as the City of Memory—the one I call home now—attempts to breathe new life in the City of Destiny, make it the great good place once more.