Bill Sorro: Difference between revisions

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) part of Molly labor series |

fixed link |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

Born in 1939, Bill grew up in San Francisco's working-class and predominantly African American Fillmore District, long before working-class folk were pushed out by Justin Herman's notorious redevelopment schemes. Coming from a family that suffered as a result of antimiscegenation laws (his Filipino father was arrested and jailed for marrying a white woman), he consistently sought to connect the struggles against class exploitation and against racial oppression. | Born in 1939, Bill grew up in San Francisco's working-class and predominantly African American Fillmore District, long before working-class folk were pushed out by Justin Herman's notorious redevelopment schemes. Coming from a family that suffered as a result of antimiscegenation laws (his Filipino father was arrested and jailed for marrying a white woman), he consistently sought to connect the struggles against class exploitation and against racial oppression. | ||

He met Giuliana “Huli” Milanese on the second Venceremos Brigade journey to Cuba and the two subsequently married in the I-Hotel in 1973. | He met [[Giuliana "Huli" Milanese|Giuliana “Huli” Milanese]] on the second Venceremos Brigade journey to Cuba and the two subsequently married in the I-Hotel in 1973. | ||

He is best known as a founding member of the I-Hotel Tenants Union, which fought for years against the evictions of the mostly senior Filipino and Chinese tenants. [[The Battle for the International Hotel|The I-Hotel]] was located in the heart of San Francisco’s historic Manilatown in the Kearny/Jackson Street area. A property developer bought the hotel and sent eviction notices in January 1977. Thousands of people rallied to keep the tenants from being evicted night after night. But the sheriff and his deputies evicted the tenants in the middle of the night in August 1977. The closing of the I-Hotel was a pivotal moment in San Francisco politics, because it united progressives and immigrants to fight for affordable housing. The Hotel was razed but the hole it left in the ground remained empty for 23 years. Then the I-Hotel was rebuilt and as an SRO for the elderly, with a Filipino American cultural center on its ground floor in great part because of Bill Sorro. | He is best known as a founding member of the I-Hotel Tenants Union, which fought for years against the evictions of the mostly senior Filipino and Chinese tenants. [[The Battle for the International Hotel|The I-Hotel]] was located in the heart of San Francisco’s historic Manilatown in the Kearny/Jackson Street area. A property developer bought the hotel and sent eviction notices in January 1977. Thousands of people rallied to keep the tenants from being evicted night after night. But the sheriff and his deputies evicted the tenants in the middle of the night in August 1977. The closing of the I-Hotel was a pivotal moment in San Francisco politics, because it united progressives and immigrants to fight for affordable housing. The Hotel was razed but the hole it left in the ground remained empty for 23 years. Then the I-Hotel was rebuilt and as an SRO for the elderly, with a Filipino American cultural center on its ground floor in great part because of Bill Sorro. | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

''Read about other Bernal Heights labor activists [[Making the Hill Red: Bernal Labor Activists|here]]. Thanks to the SF Labor Archives and Research Center, a rich source of information about union movements and working class life in the Bay Area, and the families of our subjects.'' | ''Read about other Bernal Heights labor activists [[Making the Hill Red: Bernal Labor Activists|here]]. Thanks to the SF Labor Archives and Research Center, a rich source of information about union movements and working class life in the Bay Area, and the families of our subjects.'' | ||

[[category:Labor]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:Racism]] [[category:Housing]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:1990s]] | [[category:Labor]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:Racism]] [[category:Housing]] [[category:Filipino]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:1990s]] [[category:Famous characters]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:08, 5 September 2024

Historical Essay

by Molly Martin, Gail Sansbury, Elaine Elison, and the Bernal History Project

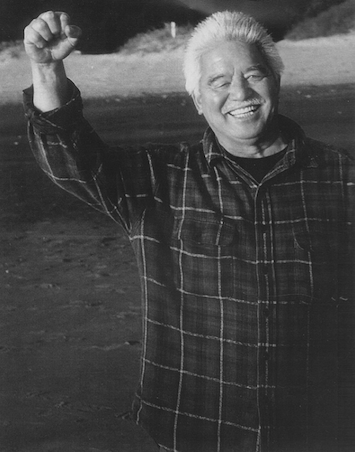

Bill Sorro, 1939-2007.

| Bernal Heights has been a center of labor activism for over a century; many prominent labor organizers can be traced there. This profile is part of a series put together by the Bernal History Project for Labor Fest in 2008 that tells the stories of six “reds” from Bernal Heights: Miriam Dinkin Johnson, Eugene Paton, Phiz Mezey, Dow Wilson, Bill Sorro, and Giuliana Milanese. |

Born in 1939, Bill grew up in San Francisco's working-class and predominantly African American Fillmore District, long before working-class folk were pushed out by Justin Herman's notorious redevelopment schemes. Coming from a family that suffered as a result of antimiscegenation laws (his Filipino father was arrested and jailed for marrying a white woman), he consistently sought to connect the struggles against class exploitation and against racial oppression.

He met Giuliana “Huli” Milanese on the second Venceremos Brigade journey to Cuba and the two subsequently married in the I-Hotel in 1973.

He is best known as a founding member of the I-Hotel Tenants Union, which fought for years against the evictions of the mostly senior Filipino and Chinese tenants. The I-Hotel was located in the heart of San Francisco’s historic Manilatown in the Kearny/Jackson Street area. A property developer bought the hotel and sent eviction notices in January 1977. Thousands of people rallied to keep the tenants from being evicted night after night. But the sheriff and his deputies evicted the tenants in the middle of the night in August 1977. The closing of the I-Hotel was a pivotal moment in San Francisco politics, because it united progressives and immigrants to fight for affordable housing. The Hotel was razed but the hole it left in the ground remained empty for 23 years. Then the I-Hotel was rebuilt and as an SRO for the elderly, with a Filipino American cultural center on its ground floor in great part because of Bill Sorro.

Sorro was also one of the first men of color to desegregate the ironworkers union under a consent decree. Before that the ironworkers union, like a lot of construction unions, discriminated against women and nonwhite men. Sorro organized a minority caucus in the union and published a newsletter called the Loadline as their communications method. Wrote Sorro and collaborator Leonard McNeil in the second issue of the newsletter, published in October 1980:

“This newsletter can be an important part of keeping our members informed about issues and questions that concern us as ironworkers in particular, and as members of the trade union movement. There are many things that affect us as workers such as racism, the non-union movement, safety, ballot measures, job conditions, affirmative action, employment, and the apprenticeship program to name a few. Those of us concerned about progressive and democratic change in our local, in the building trades, and in the labor movement need a voice to express our opinions, interests, and concerns. It is the intention of this newsletter to be a voice to unite the labor movement in the fight for jobs, for better wages, benefits and working conditions, for a more democratic union and to end race and sex discrimination.”

Legendary housing activist Bill Sorro leads an Eviction Defense rally in the late 1990s on the steps of City Hall.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Bill was also an inspirational anchor for a growing housing justice movement in San Francisco, from the Mission Anti-Displacement Coalition to the South of Market Community Action Network, as a member of the Kalayaan Collective and, later, of KDP (the Union of Democratic Filipinos), as a founder of the Manilatown Heritage Foundation, and as a mentor to countless Filipino youths — but equally among communities of color in general, for the working class in particular (as a longtime union activist and committed socialist), and ultimately for all who suffer and struggle against the indignities of oppression and exploitation.

Read about other Bernal Heights labor activists here. Thanks to the SF Labor Archives and Research Center, a rich source of information about union movements and working class life in the Bay Area, and the families of our subjects.