The Diablo Canyon Blockade 1981: Difference between revisions

added original paper scan |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

''by Ward Young and Mark Evanoff, with help from many others'' | ''by Ward Young and Mark Evanoff, with help from many others'' | ||

''(article and photos originally published in | ''(article and photos originally published in'' It's About Times ''Oct.-Nov. 1981, the Abalone Alliance Newspaper)'' | ||

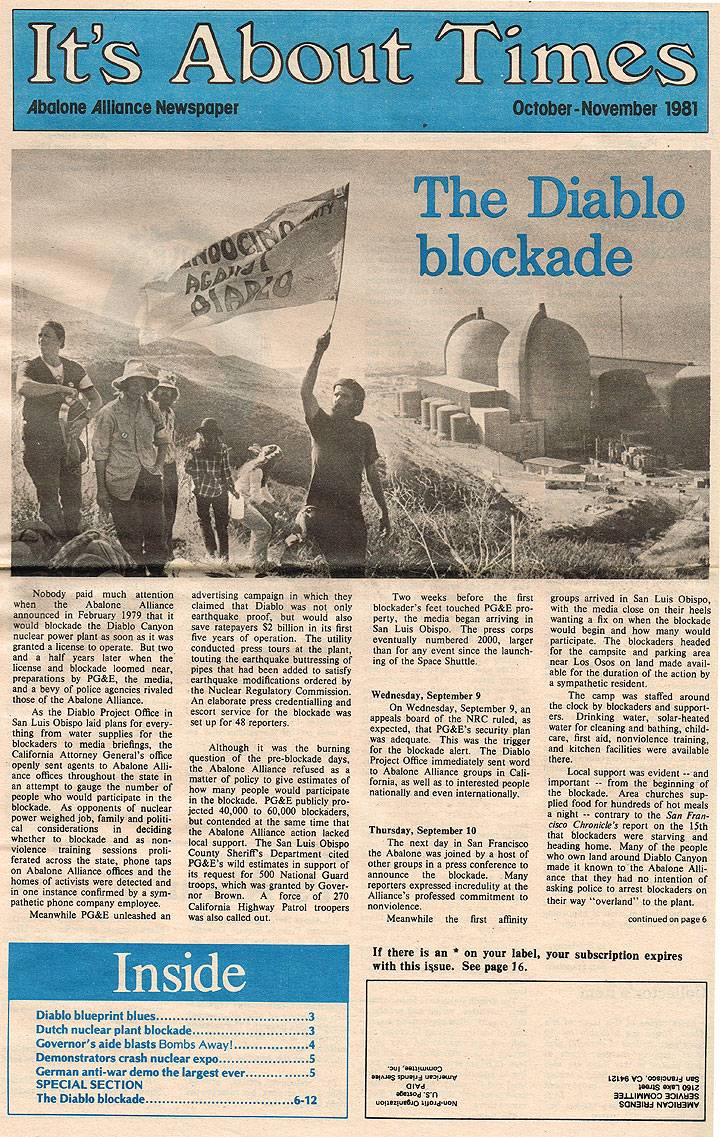

[[Image:Oct-nov-1981-IAT-cover-Diablo-Blockade.jpg]] | [[Image:Oct-nov-1981-IAT-cover-Diablo-Blockade.jpg]] | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

''Photo: Ken Chen'' | ''Photo: Ken Chen'' | ||

Nobody paid much attention when the Abalone Alliance | Nobody paid much attention when the Abalone Alliance announced in February 1979 that it would blockade the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant as soon as it was granted a license to operate. But two and a half years later when the license and blockade loomed near, preparations by PG&E, the media, and a bevy of police agencies rivaled those of the Abalone Alliance. | ||

As the Diablo Project Office in San Luis Obispo laid plans for everything from water supplies for the blockaders to media briefings, the California Attorney General's office openly sent agents to Abalone Alliance offices throughout the state in an attempt to gauge the number of people who would participate in the blockade. As opponents of nuclear power weighed job, family and political considerations in deciding whether to blockade and as nonviolence training sessions proliferated across the state, phone taps on Abalone Alliance offices and the homes of activists were detected and in one instance confirmed by a sympathetic phone company employee. | As the Diablo Project Office in San Luis Obispo laid plans for everything from water supplies for the blockaders to media briefings, the California Attorney General's office openly sent agents to Abalone Alliance offices throughout the state in an attempt to gauge the number of people who would participate in the blockade. As opponents of nuclear power weighed job, family, and political considerations in deciding whether to blockade and as nonviolence training sessions proliferated across the state, phone taps on Abalone Alliance offices and the homes of activists were detected and in one instance confirmed by a sympathetic phone company employee. | ||

Meanwhile PG&E unleashed an advertising campaign in which they claimed that Diablo was not | Meanwhile PG&E unleashed an advertising campaign in which they claimed that Diablo was not only earthquake proof, but would also save ratepayers $2 billion in its first five years of operation. The utility conducted press tours at the plant, touting the earthquake buttressing of pipes that had been added to satisfy earthquake modifications ordered by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. An elaborate press credentialing and escort service for the blockade was set up for 48 reporters. | ||

Although it was the burning question of the pre-blockade days, the Abalone Alliance refused as a matter of policy to give estimates of how many people | Although it was the burning question of the pre-blockade days, the Abalone Alliance refused as a matter of policy to give estimates of how many people would participate in the blockade. PG&E publicly projected 40,000 to 60,000 blockaders, but contended at the same time that the Abalone Alliance action lacked local support. The San Luis Obispo County Sheriff's Department cited PG&E's wild estimates in support of its request for 500 National Guard troops, which was granted by Governor Brown. A force of 270 California Highway Patrol troopers was also called out. | ||

Two weeks before the first blockader's feet touched PG&E property, the media began arriving in San Luis Obispo. The press corps eventually | Two weeks before the first blockader's feet touched PG&E property, the media began arriving in San Luis Obispo. The press corps eventually numbered 2000, larger than for any event since the launching of the Space Shuttle. | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

'''Thursday, September 10''' | '''Thursday, September 10''' | ||

The next day in San Francisco the Abalone | The next day in San Francisco the Abalone Alliance was joined by a host of other groups in a press conference to announce the blockade. Many reporters expressed incredulity at the Alliance’s professed commitment to nonviolence. | ||

Meanwhile the first affinity groups arrived in San Luis Obispo, with the media close on their heels wanting a fix on when the blockade would begin and, how many would participate. The blockaders headed for the campsite and parking area near Los Osos on land made available for the duration of the action | Meanwhile the first affinity groups arrived in San Luis Obispo, with the media close on their heels wanting a fix on when the blockade would begin and, how many would participate. The blockaders headed for the campsite and parking area near Los Osos on land made available for the duration of the action by a sympathetic resident. | ||

The camp was staffed around the clock by blockaders and supporters. Drinking water, solar-heated water for cleaning and bathing, childcare, first aid, nonviolence training, and kitchen facilities were available there. | The camp was staffed around the clock by blockaders and supporters. Drinking water, solar-heated water for cleaning and bathing, childcare, first aid, nonviolence training, and kitchen facilities were available there. | ||

Local support was evident—and important—from the beginning of the blockade. Area churches supplied food for hundreds of hot meals a night—contrary to, the San Francisco Chronicle's report on the 15th that | Local support was evident—and important—from the beginning of the blockade. Area churches supplied food for hundreds of hot meals a night—contrary to, the ''San Francisco Chronicle's'' report on the 15th that "blockaders were starving" and heading home. Many of the people who own land around Diablo Canyon made it known to the Abalone Alliance that they had no intention of asking police to arrest blockaders on their way "overland" to the plant. | ||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

'''Monday, September 14''' | '''Monday, September 14''' | ||

Before the blockade could begin, assessments of readiness by work groups | Before the blockade could begin, assessments of readiness by work groups such as transportation, legal, and on-site guides had to be completed. An attempt to reach consensus to begin the blockade on Monday failed. But on Monday afternoon, agreement was reached to begin the blockade Tuesday at noon. | ||

A subdued yet intense mood swept the encampment Monday evening as a few hundred blockaders left Los Osos to hike overland during the night. "Tomorrow morning we intend | A subdued yet intense mood swept the encampment Monday evening as a few hundred blockaders left Los Osos to hike overland during the night. "Tomorrow morning we intend to put ourselves between the workers' barracks and the fuel rods to prevent them from getting ready to load the fuel," said blockader Peter Lumsdaine. | ||

An Abalone Alliance collective of on-site guides had spent months slipping onto PG&E property to scout the area surrounding the Diablo plant. They had determined the best approaches to the reactor and built hidden trails to camouflage hikers. In the densely forested areas they had cut paths with machetes, leaving a canopy of foliage a la Ho Chi Minh trail. | An Abalone Alliance collective of on-site guides had spent months slipping onto PG&E property to scout the area surrounding the Diablo plant. They had determined the best approaches to the reactor and built hidden trails to camouflage hikers. In the densely forested areas they had cut paths with machetes, leaving a canopy of foliage a la Ho Chi Minh trail. | ||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

Several hundred reporters, photographers and spectators had gathered at the front gate in Avila Beach by 6:00 that morning. At 7:00 a.m., 700 PG&E construction workers entered by bus. As the hours wore on with no blockaders in sight, they grew frustrated and began to joke sarcastically about the action being a "media blockade." | Several hundred reporters, photographers and spectators had gathered at the front gate in Avila Beach by 6:00 that morning. At 7:00 a.m., 700 PG&E construction workers entered by bus. As the hours wore on with no blockaders in sight, they grew frustrated and began to joke sarcastically about the action being a "media blockade." | ||

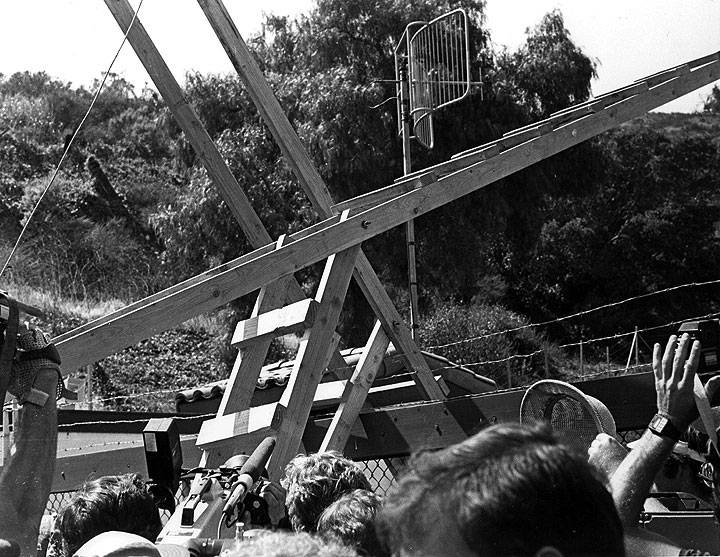

Finally, just after 1:00, three clusters of about 180 blockaders arrived at the main gate. Assault ladders were hoisted over the fence and about. 50 people jubilantly climbed over as cameras clicked and tape recorders rolled. As the blockaders hunkered down inside and outside the gate, 23 people | Finally, just after 1:00 p.m., three clusters of about 180 blockaders arrived at the main gate. Assault ladders were hoisted over the fence and about. 50 people jubilantly climbed over as cameras clicked and tape recorders rolled. As the blockaders hunkered down inside and outside the gate, 23 people who had entered the plant site a few hours earlier from nearby Wild Cherry Canyon or from the sea blockade popped up about 100 yards inside the main gate. | ||

The blockaders sat at the gate for several hours, singing songs and watching skits. Many reporters ventured onto PG&E property, some over the Abalone Alliance ladders and some through an opening in the barbed wire fence that led onto the roof of a PG&E guardhouse. In the late afternoon a PG&E employee chain sawed through the assault ladders and police brusquely told reporters to get outside the fence. | The blockaders sat at the gate for several hours, singing songs and watching skits. Many reporters ventured onto PG&E property, some over the Abalone Alliance ladders and some through an opening in the barbed wire fence that led onto the roof of a PG&E guardhouse. In the late afternoon a PG&E employee chain sawed through the assault ladders and police brusquely told reporters to get outside the fence. | ||

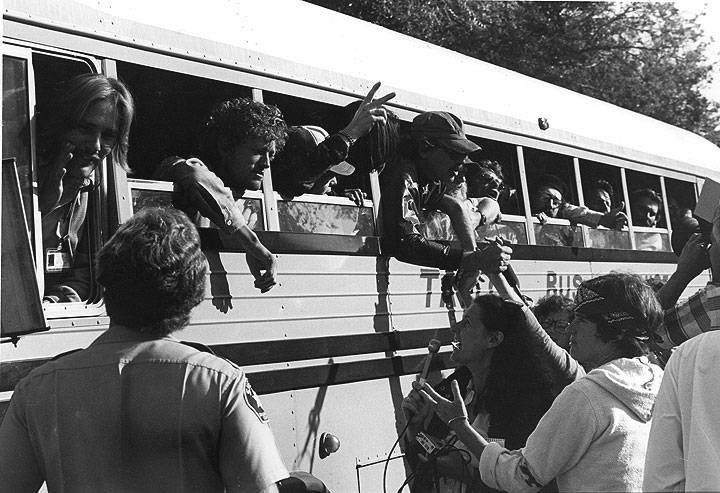

Shortly before 4:00 p.m., arrests began at the front gate. Hundreds were booked on the spot, and marked with numbers in indelible ink on their arms. They | Shortly before 4:00 p.m., arrests began at the front gate. Hundreds were booked on the spot, and marked with numbers in indelible ink on their arms. They were taken to a holding pen next to the reactor itself and kept on the buses until nearly midnight, when the men were taken to Cuesta College and the women to the California Men's Colony. Five hundred and sixty-five people in all were arrested on Tuesday. | ||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

Six hours later at 1:00 p.m., police arrested about 60 blockaders and the buses rolled in. More arrests at 5:00 p.m. allowed fourteen buses of workers and five full of arrested blockaders to exit. | Six hours later at 1:00 p.m., police arrested about 60 blockaders and the buses rolled in. More arrests at 5:00 p.m. allowed fourteen buses of workers and five full of arrested blockaders to exit. | ||

In the men's jail at Cuesta | In the men's jail at Cuesta College, forums were organized to consider different legal strategies and that evening Wavy Gravy emceed Cuesta's first "Tornado of Talent." | ||

[[Image:Diablo-prisoners-on-bus.jpg]] | [[Image:Diablo-prisoners-on-bus.jpg]] | ||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

'''Affinity group discussing their plans in camp, 1981.''' | '''Affinity group discussing their plans in camp, 1981.''' | ||

''Photo: It's About Times'' | ''Photo:'' It's About Times ''newspaper'' | ||

| Line 148: | Line 148: | ||

Roughly 100 blockaders camped Thursday night on PG&E property near See Canyon, 100 more in the hills above the plant, 150 in the Montana de Oro area and about 20 in Cherry Canyon. | Roughly 100 blockaders camped Thursday night on PG&E property near See Canyon, 100 more in the hills above the plant, 150 in the Montana de Oro area and about 20 in Cherry Canyon. | ||

No blockaders had been allowed to confer with attorneys until Thursday, the day of the first court appearances. Most of the 160 blockaders arraigned that day on charges of trespassing and blocking a public road entered pleas of not guilty | No blockaders had been allowed to confer with attorneys until Thursday, the day of the first court appearances. Most of the 160 blockaders arraigned that day on charges of trespassing and blocking a public road entered pleas of not guilty and opted to go to trial. Others pled no contest and received fines of $120 with credit of $30 a day for time already served. | ||

Two hundred and twenty-two people arrested on Tuesday had been held in jail longer than 48 hours in violation of state law, so the Abalone Alliance filed writs of habeas corpus to have them released. This action and another to change a policy of granting "own recognizance" (OR) releases only to San Luis Obispo County residents were denied. | Two hundred and twenty-two people arrested on Tuesday had been held in jail longer than 48 hours in violation of state law, so the Abalone Alliance filed writs of habeas corpus to have them released. This action and another to change a policy of granting "own recognizance" (OR) releases only to San Luis Obispo County residents were denied. | ||

| Line 160: | Line 160: | ||

Thirty sea blockaders were forced by police to climb a knotted rope to clear a beachfront cliff. Among them was Andrea Elukovich, a San Francisco deputy sheriff on leave from her job. "When I was just about to clear the tip of the bluff, a deputy kicked me so that I ended up spread-eagled in the dirt," Elukovich said. "I had dirt in my hand and I threw it in his direction. After I threw the dirt, someone grabbed me by my hair and dragged me along the bluff, while the deputy kicked me again three or four times. As I was being dragged, someone else punched me in the mouth." Elukovich was charged with a felony, which was later dropped to a misdemeanor. | Thirty sea blockaders were forced by police to climb a knotted rope to clear a beachfront cliff. Among them was Andrea Elukovich, a San Francisco deputy sheriff on leave from her job. "When I was just about to clear the tip of the bluff, a deputy kicked me so that I ended up spread-eagled in the dirt," Elukovich said. "I had dirt in my hand and I threw it in his direction. After I threw the dirt, someone grabbed me by my hair and dragged me along the bluff, while the deputy kicked me again three or four times. As I was being dragged, someone else punched me in the mouth." Elukovich was charged with a felony, which was later dropped to a misdemeanor. | ||

A bit of judicial turnabout put a snag in the district attorney's plans Friday when Judge Kenneth Lee Chatiner declined to follow the lead of previous judges who had tried to prevent demonstrators from returning to the blockade by requiring them to sign a statement. Chatiner was satisfied with the traditional | A bit of judicial turnabout put a snag in the district attorney's plans Friday when Judge Kenneth Lee Chatiner declined to follow the lead of previous judges who had tried to prevent demonstrators from returning to the blockade by requiring them to sign a statement. Chatiner was satisfied with the traditional OR promise to return for a court appearance. | ||

Chatiner also allowed defendants to be arraigned under fictitious names. At one point he asked Karen Silkwood to come forward and eight Silkwoods were arraigned at once. | Chatiner also allowed defendants to be arraigned under fictitious names. At one point he asked Karen Silkwood to come forward and eight Silkwoods were arraigned at once. | ||

| Line 172: | Line 172: | ||

More than 100 PG&E workers who had eaten and slept on the plant site since the beginning of the blockade returned home for the first time Friday night. | More than 100 PG&E workers who had eaten and slept on the plant site since the beginning of the blockade returned home for the first time Friday night. | ||

Meanwhile, in Berkeley about | Meanwhile, in Berkeley about 2,000 people demonstrated their support for the blockade in a candlelight march. | ||

[[Image:Diablo-SLO-rally.jpg]] | [[Image:Diablo-SLO-rally.jpg]] | ||

| Line 178: | Line 178: | ||

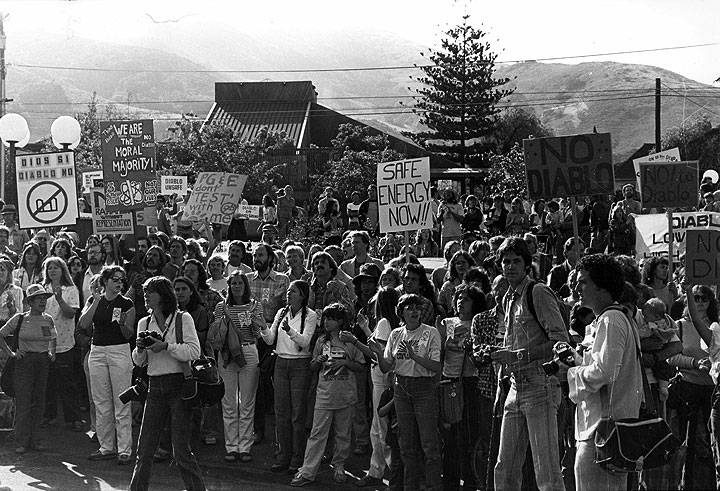

'''Local residents turn out in support of blockade, Sept. 20, 1981.''' | '''Local residents turn out in support of blockade, Sept. 20, 1981.''' | ||

''Photo: It's About Times'' | ''Photo:'' It's About Times ''newspaper'' | ||

[[Image:Diablo-not-safe.jpg]] | [[Image:Diablo-not-safe.jpg]] | ||

| Line 190: | Line 190: | ||

'''Media covering the spontaneous support demo of local citizens.''' | '''Media covering the spontaneous support demo of local citizens.''' | ||

''Photo: It's About Times'' | ''Photo:'' It's About Times ''newspaper'' | ||

'''Sunday, September 20''' | '''Sunday, September 20''' | ||

On Sunday a spontaneous and energetic demonstration in support of the blockaders drew about | On Sunday a spontaneous and energetic demonstration in support of the blockaders drew about 5,000 local residents, surprising the Abalone Alliance, PG&E, and the police alike. Older people, families with children, and engineers joined the young and hip in a march from Avila Beach to Diablo's main gate. No program of speakers and music had been organized; instead the marchers sang and talked for the rest of the afternoon. | ||

The rally had been organized in only four days. A local mother of three, Jeremy Wakefield, got the ball rolling by calling a few friends and producing a leaflet the previous Thursday. Local media picked up the story that a march unaffiliated with the Abalone Alliance would support the blockade without being part of it. | The rally had been organized in only four days. A local mother of three, Jeremy Wakefield, got the ball rolling by calling a few friends and producing a leaflet the previous Thursday. Local media picked up the story that a march unaffiliated with the Abalone Alliance would support the blockade without being part of it. | ||

| Line 210: | Line 210: | ||

Over the weekend blockade tactics were assessed and reconsidered. | Over the weekend blockade tactics were assessed and reconsidered. | ||

On Monday morning, demonstrators at the front gate divided | On Monday morning, demonstrators at the front gate divided into three groups about 100 yards apart and blockaded the road as buses full of PG&E workers escorted by National Guard trucks came driving up. | ||

The lead National Guard truck approached the first batch of blockaders without slowing down. Finally the driver slammed on his brakes, but the truck didn't stop until it was three or four feet past where the blockaders had stood until the very last second. National Guard and CHP officers then grabbed demonstrators and threw them into the back of their trucks. | The lead National Guard truck approached the first batch of blockaders without slowing down. Finally the driver slammed on his brakes, but the truck didn't stop until it was three or four feet past where the blockaders had stood until the very last second. National Guard and CHP officers then grabbed demonstrators and threw them into the back of their trucks. | ||

| Line 229: | Line 229: | ||

'''Tuesday, September 22''' | '''Tuesday, September 22''' | ||

On Tuesday arrests reached | On Tuesday arrests reached 1,483, making the Diablo blockade the largest antinuclear civil disobedience action ever in the United States. In an effort at jail solidarity, the blockaders were refusing either to be arraigned or to leave jail after serving their time until first-time offenders were released on unconditional OR. | ||

The National Guard and the CHP announced that they were leaving San Luis Obispo, confident that the sheriff's department could handle any future arrests. | The National Guard and the CHP announced that they were leaving San Luis Obispo, confident that the sheriff's department could handle any future arrests. | ||

At a hearing on jail conditions a representative of the district attorney's office argued that things couldn't be too bad since so many people were refusing to leave. He described the men's food as a smorgasbord arrangement including "vegetables, peanut butter, bologna, and bread." The women, he said, “get a hot roll and coffee for breakfast, a big lunch and a hot dinner." | At a hearing on jail conditions a representative of the district attorney's office argued that things couldn't be too bad since so many people were refusing to leave. He described the men's food as a smorgasbord arrangement including "vegetables, peanut butter, bologna, and bread." The women, he said, “get a hot roll and coffee for breakfast, a big lunch, and a hot dinner." | ||

Presiding judge William Freedman asked, "Is that chivalry or logistics?", and ordered an investigation into the possibility of providing hot meals for the men. | Presiding judge William Freedman asked, "Is that chivalry or logistics?", and ordered an investigation into the possibility of providing hot meals for the men. | ||

| Line 241: | Line 241: | ||

'''Diablo women singing and clapping.''' | '''Diablo women singing and clapping.''' | ||

''Photo: It's About Times'' | ''Photo:'' It's About Times ''newspaper'' | ||

'''Wednesday, September 23''' | '''Wednesday, September 23''' | ||

On Wednesday morning a spokes meeting at the campsite broached far the first time the subject of when and how to end the blockade. The majority reaffirmed their commitment to continue the action, and there seemed to be a general desire to hold out at | On Wednesday morning a spokes meeting at the campsite broached far the first time the subject of when and how to end the blockade. The majority reaffirmed their commitment to continue the action, and there seemed to be a general desire to hold out at least until Sunday when another local demonstration was scheduled. | ||

Members of the Revolutionary Communist Party were again ejected from the camp site, and long discussions ensued on how to cope with the RCP and other disruptive people in the camp. On Wednesday, Thursday and Friday, there were blockades and arrests at the main gate in the morning and afternoon as well as continuous actions in the back country. | Members of the Revolutionary Communist Party were again ejected from the camp site, and long discussions ensued on how to cope with the RCP and other disruptive people in the camp. On Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, there were blockades and arrests at the main gate in the morning and afternoon as well as continuous actions in the back country. | ||

'''Thursday, September 24''' | '''Thursday, September 24''' | ||

| Line 254: | Line 254: | ||

On Thursday the Public Utilities Commission and PG&E issued statements admitting that contrary to previous PG&E claims, Diablo may cost ratepayers money instead of saving them any. According to Harold Frank of PG&E, “In effect [Diablo] might increase the cost to electric companies and reduce the savings.” | On Thursday the Public Utilities Commission and PG&E issued statements admitting that contrary to previous PG&E claims, Diablo may cost ratepayers money instead of saving them any. According to Harold Frank of PG&E, “In effect [Diablo] might increase the cost to electric companies and reduce the savings.” | ||

Carol Hallet, minority leader of the California Assembly, announced a $1 million lawsuit against the Abalone Alliance, Mothers for Peace, Greenpeace and several individuals, which she said represented the cost to the state and taxpayers for extra security during the blockade. | Carol Hallet, minority leader of the California Assembly, announced a $1 million lawsuit against the Abalone Alliance, Mothers for Peace, Greenpeace, and several individuals, which she said represented the cost to the state and taxpayers for extra security during the blockade. | ||

Meanwhile, judges on the Diablo case agreed to arraign blockaders on unconditional OR. | Meanwhile, judges on the Diablo case agreed to arraign blockaders on unconditional OR. | ||

| Line 270: | Line 270: | ||

'''Sunday, September 27''' | '''Sunday, September 27''' | ||

A second rally of San Luis Obispo County residents | A second rally of San Luis Obispo County residents in support of the blockade took place at Avila Beach. About four thousand people attended. | ||

'''Monday, September 28''' | '''Monday, September 28''' | ||

On | On Monday, the final day of the blockade, two hundred people were arrested at 6:00 a.m. at the front gate. The sheriffs department was not in place and reinforcements had to be called in. Only members of the local media and Los Angeles radio station KFWB were present to report the clash. | ||

Thirty-six people in the back country hiked undetected up to the security fence that surrounds the reactor, illustrating again the vulnerability of the Diablo plant to sabotage. A PG&E Pinkerton guard finally spotted them and called police, who arrested them. | Thirty-six people in the back country hiked undetected up to the security fence that surrounds the reactor, illustrating again the vulnerability of the Diablo plant to sabotage. A PG&E Pinkerton guard finally spotted them and called police, who arrested them. | ||

| Line 296: | Line 296: | ||

'''Friday, October 2''' | '''Friday, October 2''' | ||

A second hearing was held on the issue of confiscated property. Judge Freedman had ruled earlier that the blockaders attorneys must | A second hearing was held on the issue of confiscated property. Judge Freedman had ruled earlier that the blockaders attorneys must name all defendants who wanted their property returned before he would hear the motion. The district attorney maintained that his office needed the blockaders' packs and sleeping bags in order to prove intent to trespass. | ||

But Presiding Judge Buchand told the district attorney that members of the Abalone had freely admitted their intent. “They’re glad they did it,” he pointed out. “I think your reasoning is bogus.” Buchand ordered the packs released. | But Presiding Judge Buchand told the district attorney that members of the Abalone had freely admitted their intent. “They’re glad they did it,” he pointed out. “I think your reasoning is bogus.” Buchand ordered the packs released. | ||

| Line 304: | Line 304: | ||

'''Tuesday, October 6''' | '''Tuesday, October 6''' | ||

On October 6, a court of appeals overruled the conditional OR required by San Luis Obispo judges. Unfortunately a written decision was not issued and no precedent will | On October 6, a court of appeals overruled the conditional OR required by San Luis Obispo judges. Unfortunately a written decision was not issued and no precedent will be set for future cases. | ||

'''Friday, October 16''' | '''Friday, October 16''' | ||

| Line 312: | Line 312: | ||

[[Diablo Canyon Blockade Tales|Personal accounts of blockading Diablo Canyon]] | [[Diablo Canyon Blockade Tales|Personal accounts of blockading Diablo Canyon]] | ||

<hr> | |||

[[Image:Foundsf-anti-nukes-icon.gif|link=Diablo Canyon Blockade Tales]] [[Diablo Canyon Blockade Tales| Continue Anti-Nuke Tour]] | |||

[[category:anti-nuclear]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:San Francisco outside the city]] | [[category:anti-nuclear]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:San Francisco outside the city]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:15, 3 July 2024

"I was there..."

by Ward Young and Mark Evanoff, with help from many others

(article and photos originally published in It's About Times Oct.-Nov. 1981, the Abalone Alliance Newspaper)

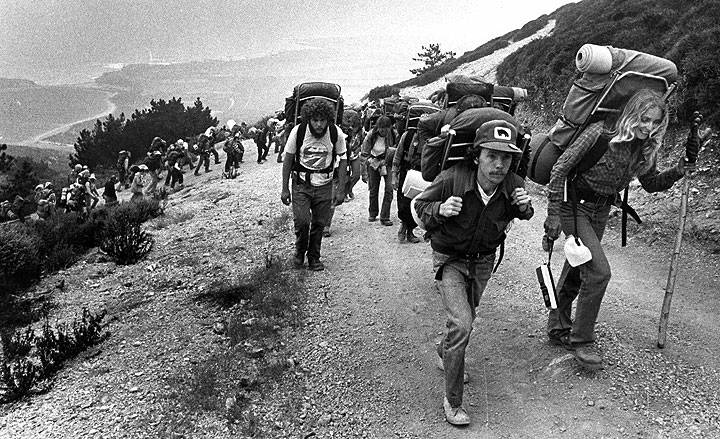

Diablo blockaders hike up dusty road to camp, 1981.

Photo: Ken Chen

Nobody paid much attention when the Abalone Alliance announced in February 1979 that it would blockade the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant as soon as it was granted a license to operate. But two and a half years later when the license and blockade loomed near, preparations by PG&E, the media, and a bevy of police agencies rivaled those of the Abalone Alliance.

As the Diablo Project Office in San Luis Obispo laid plans for everything from water supplies for the blockaders to media briefings, the California Attorney General's office openly sent agents to Abalone Alliance offices throughout the state in an attempt to gauge the number of people who would participate in the blockade. As opponents of nuclear power weighed job, family, and political considerations in deciding whether to blockade and as nonviolence training sessions proliferated across the state, phone taps on Abalone Alliance offices and the homes of activists were detected and in one instance confirmed by a sympathetic phone company employee.

Meanwhile PG&E unleashed an advertising campaign in which they claimed that Diablo was not only earthquake proof, but would also save ratepayers $2 billion in its first five years of operation. The utility conducted press tours at the plant, touting the earthquake buttressing of pipes that had been added to satisfy earthquake modifications ordered by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. An elaborate press credentialing and escort service for the blockade was set up for 48 reporters.

Although it was the burning question of the pre-blockade days, the Abalone Alliance refused as a matter of policy to give estimates of how many people would participate in the blockade. PG&E publicly projected 40,000 to 60,000 blockaders, but contended at the same time that the Abalone Alliance action lacked local support. The San Luis Obispo County Sheriff's Department cited PG&E's wild estimates in support of its request for 500 National Guard troops, which was granted by Governor Brown. A force of 270 California Highway Patrol troopers was also called out.

Two weeks before the first blockader's feet touched PG&E property, the media began arriving in San Luis Obispo. The press corps eventually numbered 2000, larger than for any event since the launching of the Space Shuttle.

The check-in desk at camp.

Photo: Bob Van Scoy

Wednesday, September 9

On Wednesday, September 9, an appeals board of the NRC ruled, as expected, that PG&E's security plan was adequate. This was the trigger for the blockade alert. The Diablo Project Office immediately sent word to Abalone Alliance groups in California, as well as to interested people nationally and even internationally.

Thursday, September 10

The next day in San Francisco the Abalone Alliance was joined by a host of other groups in a press conference to announce the blockade. Many reporters expressed incredulity at the Alliance’s professed commitment to nonviolence.

Meanwhile the first affinity groups arrived in San Luis Obispo, with the media close on their heels wanting a fix on when the blockade would begin and, how many would participate. The blockaders headed for the campsite and parking area near Los Osos on land made available for the duration of the action by a sympathetic resident.

The camp was staffed around the clock by blockaders and supporters. Drinking water, solar-heated water for cleaning and bathing, childcare, first aid, nonviolence training, and kitchen facilities were available there.

Local support was evident—and important—from the beginning of the blockade. Area churches supplied food for hundreds of hot meals a night—contrary to, the San Francisco Chronicle's report on the 15th that "blockaders were starving" and heading home. Many of the people who own land around Diablo Canyon made it known to the Abalone Alliance that they had no intention of asking police to arrest blockaders on their way "overland" to the plant.

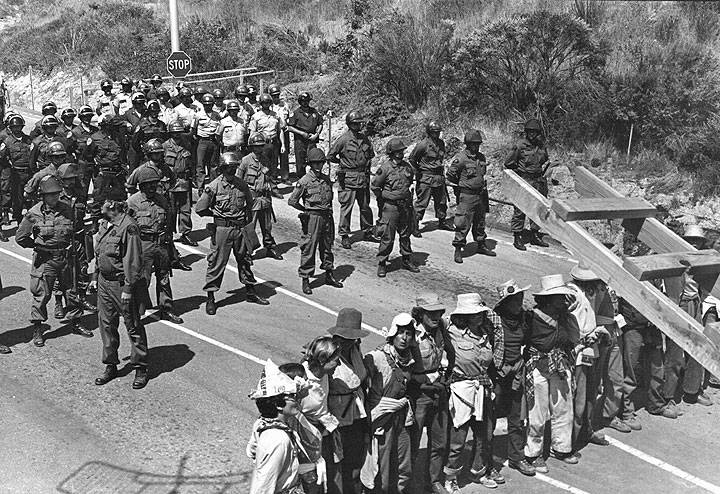

The Mother Bear Brigade meets the Sheriff's Department inside the main gate.

Photo: Steve Stallone

The weekend of September 11 to 13

Hundreds of blockaders and supporters streamed into the camp between Friday and Sunday. Affinity groups were briefed on the obstacles they might encounter on the three overland routes, at the main gate or as part of the sea blockade. On Sunday the affinity groups formed clusters of 50 to 100 people who would blockade together.

Among the dozens of affinity groups at the camp was one called Red Fox that was made up of members of the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). Red Fox very loudly made known their preference for responding in kind to any police violence. The RCP has tried repeatedly to gain entrance to the antinuclear movement, but its hortatory and hierarchical style have always turned off antinuclear activists. RCP members were asked to leave the campsite, and throughout the weekend groups of Abalone "peacekeepers" tried, sometimes unsuccessfully, to hustle them out. One result was heightened security and a touch of paranoia at the camp.

Monday, September 14

Before the blockade could begin, assessments of readiness by work groups such as transportation, legal, and on-site guides had to be completed. An attempt to reach consensus to begin the blockade on Monday failed. But on Monday afternoon, agreement was reached to begin the blockade Tuesday at noon.

A subdued yet intense mood swept the encampment Monday evening as a few hundred blockaders left Los Osos to hike overland during the night. "Tomorrow morning we intend to put ourselves between the workers' barracks and the fuel rods to prevent them from getting ready to load the fuel," said blockader Peter Lumsdaine.

An Abalone Alliance collective of on-site guides had spent months slipping onto PG&E property to scout the area surrounding the Diablo plant. They had determined the best approaches to the reactor and built hidden trails to camouflage hikers. In the densely forested areas they had cut paths with machetes, leaving a canopy of foliage a la Ho Chi Minh trail.

These preparations allowed hundreds of blockaders to roam the area freely for days, even approaching within shouting distance of the reactors themselves. Helicopters and infra-red scanners notwithstanding, the National Guard and police did not detect them. These successful breaches of PG&E's security illustrated the vulnerability of the Diablo plant to sabotage.

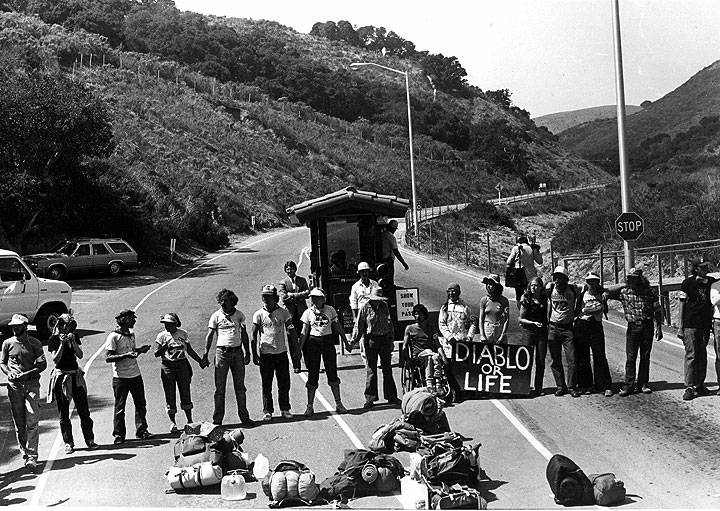

Blockading main road at main gate to the plant at Avila Beach.

Photo: Steve Stallone

Diablo police use a nose hold in making first arrest at main gate, Tuesday, September 15, 1981.

Photo: Steve Stallone

Tuesday, September 15

The sea blockade began early Tuesday morning when eight boats left Port San Luis. They rendezvoused with two more from Morro Bay and headed toward the eight-by-two-mile area of ocean around the plant that the Coast Guard had declared off limits, ostensibly for safety reasons. After a few maneuvers to avoid two Coast Guard cutters, 20 blockaders climbed into Zodiac rubber rafts and landed at 11:00 a.m. about a mile south of the Coast Guard's safety zone and five miles from the plant. Violators of the zone faced up to $50,000 fines, five years imprisonment and seizure of their boats.

Several hundred reporters, photographers and spectators had gathered at the front gate in Avila Beach by 6:00 that morning. At 7:00 a.m., 700 PG&E construction workers entered by bus. As the hours wore on with no blockaders in sight, they grew frustrated and began to joke sarcastically about the action being a "media blockade."

Finally, just after 1:00 p.m., three clusters of about 180 blockaders arrived at the main gate. Assault ladders were hoisted over the fence and about. 50 people jubilantly climbed over as cameras clicked and tape recorders rolled. As the blockaders hunkered down inside and outside the gate, 23 people who had entered the plant site a few hours earlier from nearby Wild Cherry Canyon or from the sea blockade popped up about 100 yards inside the main gate.

The blockaders sat at the gate for several hours, singing songs and watching skits. Many reporters ventured onto PG&E property, some over the Abalone Alliance ladders and some through an opening in the barbed wire fence that led onto the roof of a PG&E guardhouse. In the late afternoon a PG&E employee chain sawed through the assault ladders and police brusquely told reporters to get outside the fence.

Shortly before 4:00 p.m., arrests began at the front gate. Hundreds were booked on the spot, and marked with numbers in indelible ink on their arms. They were taken to a holding pen next to the reactor itself and kept on the buses until nearly midnight, when the men were taken to Cuesta College and the women to the California Men's Colony. Five hundred and sixty-five people in all were arrested on Tuesday.

Diablo blockaders go over the front gate on ladders.

Photo: Paula von Leewenfeld

Assault ladders are hoisted over the fence at the main gate.

Photo: Steve Stallone

Wednesday, September 16

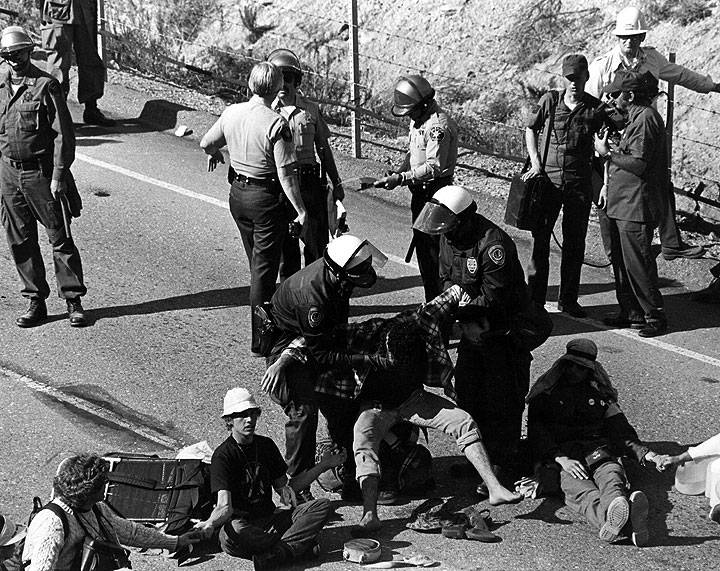

Police used a minimum of force throughout the first day of the blockade, although one woman got a fractured wrist during her arrest. But on Wednesday the tension heightened as police used choke holds and wrist locks and jabbed their batons against blockaders.

Early in the day, three Greenpeace Zodiacs outmaneuvered Coast Guard cutters and landed twelve swimmers in Stillwater Cove directly in front of Diablo Canyon, ignoring warnings to stay out of the area. Seven crew members were arrested at Port San Luis and their boats seized. Marshall Phillips, an AP reporter who had asked to accompany the flotilla, was also arrested.

At the main gate, a spontaneous action by a woman who hadn't planned to blockade succeeded in preventing 600 PG&E workers from entering the plant site for six hours. Itara Katherine O'Connell sat down in front of the gate when it was suddenly swung open to allow fourteen busloads of PG&E workers to enter. O'Connell stayed on the ground. "It was the only way I could think of to stop that bus," she explained afterward. "I thought he was going to run me over."

O'Connell held onto the front bumper as PG&E driver Joe Heck, wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the slogan "I ran the Diablo blockade," inched the bus forward until only O'Connell's head and shoulders were visible. Finally he stopped and the caravan turned around.

Six hours later at 1:00 p.m., police arrested about 60 blockaders and the buses rolled in. More arrests at 5:00 p.m. allowed fourteen buses of workers and five full of arrested blockaders to exit.

In the men's jail at Cuesta College, forums were organized to consider different legal strategies and that evening Wavy Gravy emceed Cuesta's first "Tornado of Talent."

Blockaders on a jail bus meet the press as they arrive for arraignment.

Photo: Bob Van Scoy

Affinity group discussing their plans in camp, 1981.

Photo: It's About Times newspaper

Thursday, September 17

Thursday saw arrests at the front gate, at the sea blockade and in the back country hills surrounding the reactor.

At dawn an unidentified CHP officer jumped out of his car, grabbed his shotgun and took aim at a group of blockaders at the front gate. But he put it away when confronted by a reporter. About 60 arrests were made at the front gate shortly after 5:00 a.m. and another 26 were arrested in the evening as police cleared the road for PG&E buses to leave.

Police were now routinely roughing up blockaders while making arrests or clearing pathways, more violently when no reporters were around. David Broadwater of Atascadero, who was recognized by police as an antinuclear (but unsuccessful) candidate for the county board of supervisors, reported that police threw him down an embankment and hit him in the head with a baton. His glasses were deliberately smashed.

A news team from Cable News Network and a photographer for the San Francisco Examiner were arrested as authorities cracked down on news media they claimed were uncooperative.

Roughly 100 blockaders camped Thursday night on PG&E property near See Canyon, 100 more in the hills above the plant, 150 in the Montana de Oro area and about 20 in Cherry Canyon.

No blockaders had been allowed to confer with attorneys until Thursday, the day of the first court appearances. Most of the 160 blockaders arraigned that day on charges of trespassing and blocking a public road entered pleas of not guilty and opted to go to trial. Others pled no contest and received fines of $120 with credit of $30 a day for time already served.

Two hundred and twenty-two people arrested on Tuesday had been held in jail longer than 48 hours in violation of state law, so the Abalone Alliance filed writs of habeas corpus to have them released. This action and another to change a policy of granting "own recognizance" (OR) releases only to San Luis Obispo County residents were denied.

Friday, September 18

A caravan of PG&E workers in buses and cars were briefly delayed Friday morning by two groups of blockaders who had earlier climbed the front gate fence. Thirty-seven arrests were made there, and 25 more at the Montana de Oro access route.

Ten blockaders in four boats left Port San Luis and arrived near Pecho Creek at 6:45 a.m. to set up a second base camp. The' boats were imperiled by police helicopters which buzzed them below mast height to create swells big enough to capsize them.

Thirty sea blockaders were forced by police to climb a knotted rope to clear a beachfront cliff. Among them was Andrea Elukovich, a San Francisco deputy sheriff on leave from her job. "When I was just about to clear the tip of the bluff, a deputy kicked me so that I ended up spread-eagled in the dirt," Elukovich said. "I had dirt in my hand and I threw it in his direction. After I threw the dirt, someone grabbed me by my hair and dragged me along the bluff, while the deputy kicked me again three or four times. As I was being dragged, someone else punched me in the mouth." Elukovich was charged with a felony, which was later dropped to a misdemeanor.

A bit of judicial turnabout put a snag in the district attorney's plans Friday when Judge Kenneth Lee Chatiner declined to follow the lead of previous judges who had tried to prevent demonstrators from returning to the blockade by requiring them to sign a statement. Chatiner was satisfied with the traditional OR promise to return for a court appearance.

Chatiner also allowed defendants to be arraigned under fictitious names. At one point he asked Karen Silkwood to come forward and eight Silkwoods were arraigned at once.

In response to these heresies the district attorney exercised his right to remove a judge from the case without cause. Undeterred, Chatiner continued to challenge the treatment of blockaders by the district attorney's office. He ordered the release of confiscated backpacks, but the district attorney took immediate steps to have the order stayed in Superior Court.

At the end of the arraignment Chatiner "twinkled" the defendants as he left the courtroom. "Twinkling" is a gesture of support developed by the Abalone Alliance. You shake your hands above your head as a silent form of applauding without disrupting a meeting.

Early arrestees who had pled no contest were released from jail beginning on Friday. Mass arraignments also began, with groups of 50 blockaders making pleas at once.

More than 100 PG&E workers who had eaten and slept on the plant site since the beginning of the blockade returned home for the first time Friday night.

Meanwhile, in Berkeley about 2,000 people demonstrated their support for the blockade in a candlelight march.

Local residents turn out in support of blockade, Sept. 20, 1981.

Photo: It's About Times newspaper

Local residents march in support of the blockade on September 20th.

Photo: Bob Van Scoy

Media covering the spontaneous support demo of local citizens.

Photo: It's About Times newspaper

Sunday, September 20

On Sunday a spontaneous and energetic demonstration in support of the blockaders drew about 5,000 local residents, surprising the Abalone Alliance, PG&E, and the police alike. Older people, families with children, and engineers joined the young and hip in a march from Avila Beach to Diablo's main gate. No program of speakers and music had been organized; instead the marchers sang and talked for the rest of the afternoon.

The rally had been organized in only four days. A local mother of three, Jeremy Wakefield, got the ball rolling by calling a few friends and producing a leaflet the previous Thursday. Local media picked up the story that a march unaffiliated with the Abalone Alliance would support the blockade without being part of it.

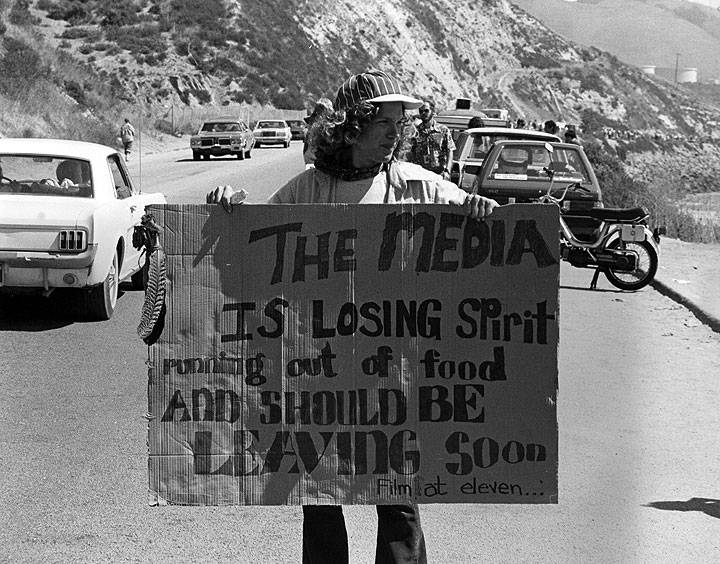

In the San Francisco area and elsewhere, news media had to backtrack a bit from earlier stories that portrayed local residents as hostile to the blockade. One marcher's sign read, "Media is losing spirit, running out of food and will be gone soon." Many at the rally expressed their thanks to the blockaders.

Photo: Steve Stallone

Monday, September 21

Over the weekend blockade tactics were assessed and reconsidered.

On Monday morning, demonstrators at the front gate divided into three groups about 100 yards apart and blockaded the road as buses full of PG&E workers escorted by National Guard trucks came driving up.

The lead National Guard truck approached the first batch of blockaders without slowing down. Finally the driver slammed on his brakes, but the truck didn't stop until it was three or four feet past where the blockaders had stood until the very last second. National Guard and CHP officers then grabbed demonstrators and threw them into the back of their trucks.

Later that day a cluster of affinity groups that had hiked in from Montana de Oro blockaded the Avila Road between the gate entrance and the plant. The sheriff's department, angered at their sudden appearance, roughed up the men in the group and threw everyone into trucks before formally charging them with resisting arrest. A PG&E employee who tried to give the blockaders a warning to leave was cut off by police.

Reverend Cecil Williams of Glide Memorial Church in San Francisco joined the blockade that afternoon. Newspapers reports described the scene as a "return to the sixties" because demonstrators handed flowers to the police.

Also on Monday, as anticipated, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission granted PG&E a low power test permit for the Diablo reactor. But unexpectedly, three of the commissioners voiced doubts about various safety aspects of the plant. One of them, Victor Gilinsky, called the security hearings held by the NRC appeals board "shoddy."

Diablo protester arrested.

Photo: Barbara Bowman

Tuesday, September 22

On Tuesday arrests reached 1,483, making the Diablo blockade the largest antinuclear civil disobedience action ever in the United States. In an effort at jail solidarity, the blockaders were refusing either to be arraigned or to leave jail after serving their time until first-time offenders were released on unconditional OR.

The National Guard and the CHP announced that they were leaving San Luis Obispo, confident that the sheriff's department could handle any future arrests.

At a hearing on jail conditions a representative of the district attorney's office argued that things couldn't be too bad since so many people were refusing to leave. He described the men's food as a smorgasbord arrangement including "vegetables, peanut butter, bologna, and bread." The women, he said, “get a hot roll and coffee for breakfast, a big lunch, and a hot dinner."

Presiding judge William Freedman asked, "Is that chivalry or logistics?", and ordered an investigation into the possibility of providing hot meals for the men.

Diablo women singing and clapping.

Photo: It's About Times newspaper

Wednesday, September 23

On Wednesday morning a spokes meeting at the campsite broached far the first time the subject of when and how to end the blockade. The majority reaffirmed their commitment to continue the action, and there seemed to be a general desire to hold out at least until Sunday when another local demonstration was scheduled.

Members of the Revolutionary Communist Party were again ejected from the camp site, and long discussions ensued on how to cope with the RCP and other disruptive people in the camp. On Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, there were blockades and arrests at the main gate in the morning and afternoon as well as continuous actions in the back country.

Thursday, September 24

On Thursday the Public Utilities Commission and PG&E issued statements admitting that contrary to previous PG&E claims, Diablo may cost ratepayers money instead of saving them any. According to Harold Frank of PG&E, “In effect [Diablo] might increase the cost to electric companies and reduce the savings.”

Carol Hallet, minority leader of the California Assembly, announced a $1 million lawsuit against the Abalone Alliance, Mothers for Peace, Greenpeace, and several individuals, which she said represented the cost to the state and taxpayers for extra security during the blockade.

Meanwhile, judges on the Diablo case agreed to arraign blockaders on unconditional OR.

Friday, September 25

Blockading continued at the front gate. William Bennett, the only member of the Public Utilities Commission to oppose the construction of Diablo Canyon in 1967, stopped by to offer his support of the blockade. Bennett is currently chairman of the State Board of Equalization. "Diablo Canyon was undemocratically approved," he said. "These people are to be commended."

Women arrestees' were removed from the Men's Colony on Friday and taken to the County Jail Honor Farm, where conditions were crowded with no space at all between mattresses. The men were taken from Cuesta College to the Men's Colony.

Saturday, September 26

After an eight-hour meeting on Saturday, consensus was reached to end what was called "Phase One" of the blockade. A last blockade attempt was scheduled for Monday.

Sunday, September 27

A second rally of San Luis Obispo County residents in support of the blockade took place at Avila Beach. About four thousand people attended.

Monday, September 28

On Monday, the final day of the blockade, two hundred people were arrested at 6:00 a.m. at the front gate. The sheriffs department was not in place and reinforcements had to be called in. Only members of the local media and Los Angeles radio station KFWB were present to report the clash.

Thirty-six people in the back country hiked undetected up to the security fence that surrounds the reactor, illustrating again the vulnerability of the Diablo plant to sabotage. A PG&E Pinkerton guard finally spotted them and called police, who arrested them.

An occupation of PG&E offices in San Luis Obispo was staged by members of the Feminist Cluster. They delivered a citizens arrest form to PG&E’s William Seavy. Eighteen were arrested there at the end of the day, bringing total arrests for the Diablo blockade to 1901.

The same day PG&E announced that a serious safety problem had been found in the plant. Engineers had discovered on Sunday that the blueprints for a piping support system in Unit One had been mixed up with those from Unit Two. The NRC ordered fuel loading halted, just as it was about to begin.

Tuesday, September 29

Faced with empty courtrooms as a result of jail solidarity, the courts agreed to extend unconditional release to everyone. They also said they would arraign people in the order of their arrest.

Wednesday, September 30

Sentences for first offenders were reduced to three days. Second time offenders were being sentenced to 14 days in jail and fined $300.

Thursday, October 1

The last remaining blockaders in jail were released after signing paper arraignments, with no court appearances necessary. That evening the women guards from the California Department of Corrections partied with their prisoners. They were presented with Stop Diablo T-shirts by the Running on Empty affinity group, and then bought their own complete sets of antinuclear T-shirts.

Friday, October 2

A second hearing was held on the issue of confiscated property. Judge Freedman had ruled earlier that the blockaders attorneys must name all defendants who wanted their property returned before he would hear the motion. The district attorney maintained that his office needed the blockaders' packs and sleeping bags in order to prove intent to trespass.

But Presiding Judge Buchand told the district attorney that members of the Abalone had freely admitted their intent. “They’re glad they did it,” he pointed out. “I think your reasoning is bogus.” Buchand ordered the packs released.

By this time most of the blockaders had left town and the blockaders had left town and the camp was almost completely dismantled.

Tuesday, October 6

On October 6, a court of appeals overruled the conditional OR required by San Luis Obispo judges. Unfortunately a written decision was not issued and no precedent will be set for future cases.

Friday, October 16

Charges against Greenpeace were dropped on October 16.

Personal accounts of blockading Diablo Canyon