Bay Area Collectives in the Early 1980s: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>"I was there..."</font></font> </font>''' ''A Discussion Between Geoff Kozeny and John Curl, 1986'' 350px|left On March 8, 1986, I sat with Geoph Kozeny, primary editor of the ''Grapevine/Collective Networker Newsletter'', on the back porch of Stardance House in San Francisco and, between scattered showers, we discussed our experiences. This dialogue was...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

Another heated issue was that we defined ourselves as an "open collective". To some of us this meant we were "open" to all ideas, that we encouraged participation and feedback from anyone involved or interested in the broader community. To the advocates of internal struggle, being "open" meant that anybody who wanted to be involved, could be involved. If somebody showed up at production they had to be plugged in. | Another heated issue was that we defined ourselves as an "open collective". To some of us this meant we were "open" to all ideas, that we encouraged participation and feedback from anyone involved or interested in the broader community. To the advocates of internal struggle, being "open" meant that anybody who wanted to be involved, could be involved. If somebody showed up at production they had to be plugged in. | ||

[[ | [[Image:THE-INTERCOLLECTIVE-classes-and-workshops-spring-1983.jpg|350px|left]] | ||

The less radical faction, I’d say the more practical faction, wanted a group in which a new person had to establish a track record before having a full say and jumping into the middle of production. We wanted to know who was a member of the group and who wasn’t, and wanted members who could be depended on. It felt like we weren’t really able to move forward, as though at each meeting we were always reinventing the wheel. | The less radical faction, I’d say the more practical faction, wanted a group in which a new person had to establish a track record before having a full say and jumping into the middle of production. We wanted to know who was a member of the group and who wasn’t, and wanted members who could be depended on. It felt like we weren’t really able to move forward, as though at each meeting we were always reinventing the wheel. | ||

Revision as of 19:42, 29 May 2023

"I was there..."

A Discussion Between Geoff Kozeny and John Curl, 1986

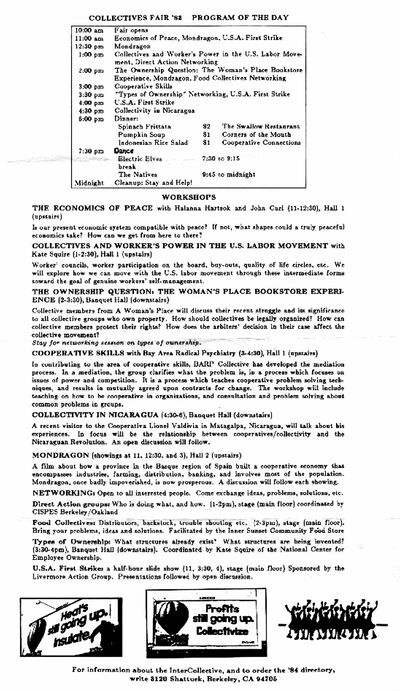

On March 8, 1986, I sat with Geoph Kozeny, primary editor of the Grapevine/Collective Networker Newsletter, on the back porch of Stardance House in San Francisco and, between scattered showers, we discussed our experiences. This dialogue was printed in the Collective Networker #97, June 1986.

GEOPH KOZENY: Though the current wave of collectives had its roots in the 60’s, my first real contact with the network came early in 1978, when I found a newly-formed housing group in Berkeley and North Oakland, the Communal Grapevine. They organized monthly meetings for people who wanted to live communally. One woman active in the group, Yana Parker, started a monthly newsletter about what was going on. The first issue of the Grapevine (which later became the Collective Networker Newsletter) was in March 1978. I randomly went to a few meetings. I was peripherally involved with the network and the newsletter, and I subscribed to it. But my connection was more a personal one with Yana.

Soon thereafter we got our communal house, Stardance, going here in San Francisco. With a couple of friends in other houses, I began working to launch a San Francisco version of the Grapevine. We put out one or two simple fliers before we took on a monthly column in the other Grapevine, in effect merging the focus from both sides of the bay.

Early in 1980 Yana put out the word that she wanted to retire as editor. She’d been doing the newsletter about group living for two years, but was still pretty much the only person doing it. It seemed inappropriate to her — she wanted it collectivized. In no time there were about twelve people working on it, and it jumped from eight or ten pages to a twenty-four page production. I got involved with the second collectivized issue. We didn’t have any organizational structure, any system for coordinating our efforts. There was a lot of chaos. After two months of this, Yana felt so frustrated by our process — needing everything planned by consensus of a big group that didn’t know what it was doing — that she dropped out. So it was left in the lap of the group, some of who had very little connection with what the newsletter had been in the past, or who the subscribers were.

Quickly the focus changed from housing to self-management, third-world issues, things like that. A more political and economic focus. I tried to make sure that the group living focus wasn’t entirely abandoned. I started taking responsibility for the Community Calendar and for perpetuating the monthly "housing raps." At first a lot of people had lots of enthusiasm. After producing a few more issues without developing a smoother system of organization, people started to get burned out and the number of staff dwindled.

At about this same time I got involved with the Directory, in the spring of 1980. I hadn’t heard of it until then, although two previous editions had come out, in 1976 and ‘77. I was invited to participate by some of the people I was working with on the Grapevine. I remember the first meeting I attended, to discuss the focus and content of a new Directory, and to brainstorm ways to involve more of the collectives in the area, to generate a dialog. I think that’s where I met you, too, at that meeting.

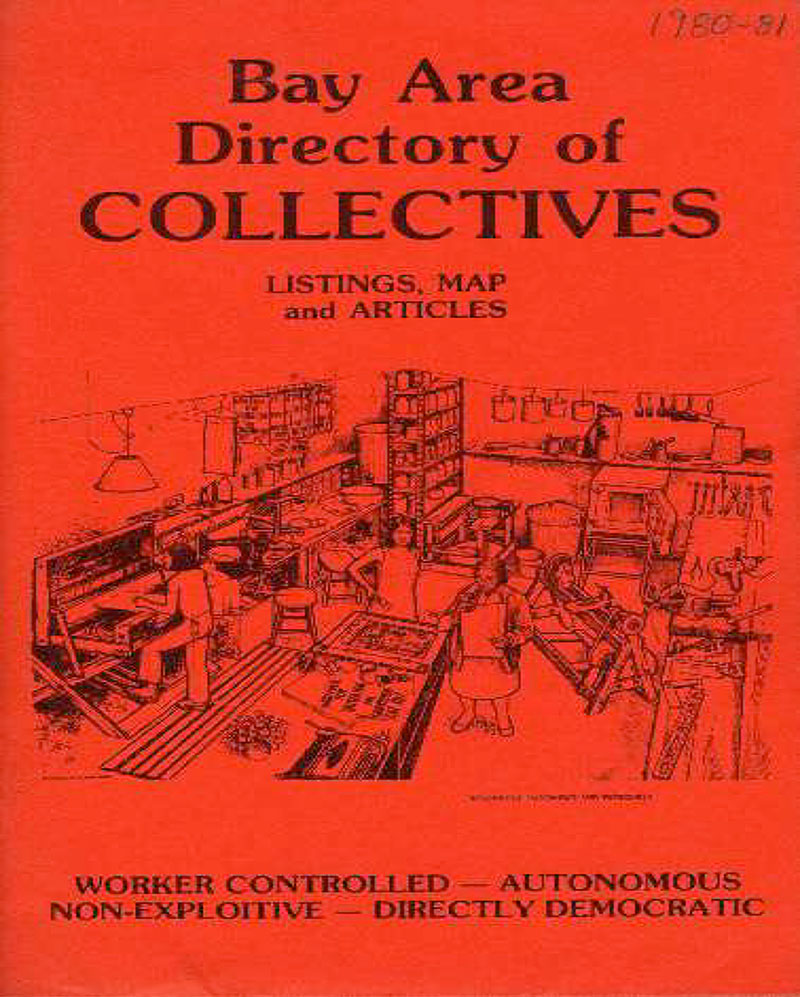

1980-81 Directory

JOHN CURL: You’re right. I became involved with publishing the Directory, I attended the very first organizing meeting, back in ‘76, and had an article in the ‘77 booklet. I didn’t hear about the Grapevine until later, probably through you, although I’d been involved with an earlier phase of the local network.

During the years that the Food System rose and fell, since I was working collectively in a non- food industry, I was not connected with what happened, although I heard a lot about it. The issues of centralism and decentralism, "third world" questions, and connections with the prisoners’ movement in those radicalized times of the mid-70s, broke it into factions, and in 1977 it split at the seams, clouded by charges that the disruption was done intentionally as part of Richard Nixon’s Cointelpro undercover operation, that was destroying many other organizations at the time.

The dust had not yet settled on the Food System disaster when I became involved with the 1980 Collectives Directory. The first Directory, in 1976, was just a poster with a little over a hundred listings. The second Directory was also a poster, with a map and alphabetical listings on one side, and categorical listings on the other. There was also a little newsprint booklet that accompanied it, with articles. The problem with the 1977 edition was that the articles, listings, and map were not really connected. We wanted to include all three in the new 1980 edition, and we came up with a folded cover flap that the map tucked into.

We planned on running a group of articles, each on a different Bay Area collective. But some people in the group were dissatisfied with it, and thought it wasn’t political enough. We came up with the idea of tape recording a conversation in which we — and other people we’d invite — would discuss controversial issues of the collective movement. We would edit the tape down so that the final result would be a dialog of different points of view. We hoped that this would fill the gap.

GEOPH: I remember what a major issue the dialog question became. We kept looking for ways to broaden the participation, to get feedback. I don’t think we were really very good at that, and really didn’t follow through. So the process of getting it together dragged on for months, and seemed to be getting nowhere. The meager response was discouraging. We started having personal conflicts within the group Should we get into this?

JOHN: I guess we have to. The problems we had aren’t unique to us they crop up in lots of groups when people are trying to share responsibility and make collective decisions.

GEOPH: Several of the same people worked on both the Grapevine and the Directory, and the conflicts we had in one spilled over to the other. The issues weren’t exactly the same, but similar. Later the same people butted heads in the Intercollective.

One main difference was reflected in our different approaches for bringing about social changes, the old debate of "reform or revolution?" But that question wasn’t really the problem, it was more that we disagreed about process, and that prevented us from getting the work done. One group of people very involved in the production of both the Grapevine and the Directory, were always rewriting and re-editing and changing things at the end. Some of us felt it was hard to get anything accomplished, and if you did, it might all be changed at the last minute.

JOHN: I certainly was frustrated by the lack of progress. Once you thought you had an agreement and you started working on a plan, they would come up with what they thought was a better plan or a better idea... and all prior agreements went out the window. Some of the same people who had wanted to include "the dialog" in the Directory decided they were not satisfied with the way it turned out, and blocked production.

We were functioning by consensus, which we had not clearly defined, and we had no precedent for how to deal with the situation. What does a consensus group do when one or two people are constantly blocking, or when it has broken into factions? In this instance, we brought out the 1980 Directory by a compromise — adding two articles at the end which more or less described our internal struggles and tried to draw a parallel to the factionalism that was undermining the broader "movement".

GEOPH: Right. The self-critical article, "The Reincarnation of the Rebel Spirit," was really a very thoughtful and moving call for everyone to examine their priorities and their daily lives, to drop self-limiting fears, to pool resources and create a dynamic support network — in effect, to really identify our values and goals, to set clear priorities, and to mount an all-out effort to live up to them.

The response article, "A Reformist’s Postscript", which I [Geoph] wrote, endorsed much of the first article while noting that our "good" ideas would certainly alienate rather than unite people, because we were presenting ourselves as having "The Answer" rather than simply sharing our experiences and our insights. My other criticism, not unrelated to the first, was that our own internal process had been so frustrating, so overwhelmingly full of conflict, that I could hardly point to us as a shining example of the cooperative spirit. We didn’t seem capable of following our own standards.

Meanwhile, we were having related problems in the Grapevine staff, involving some of the same people. There were aspects of factions, but there were really no consistent groupings or lines.

There were major tendencies that were pretty easy to see. It came to be centered around the more revolution-oriented people on one side, who mostly lived together. They embraced the struggle of conflict between people as a growth process. They encouraged it. They discussed things among themselves beforehand, and at our meetings it felt like we were dealing with a block while the rest of us acted as individuals. On any given issue others would line up either with them or against them. After a while some individuals would line up against them pretty consistently, but a real opposing faction never formed.

Soon after the 1980 Directory came out, the first Intercollective meetings were held. This was in the fall. The earliest ones were held at the Swallow, a collective restaurant in Berkeley, and primarily food-related groups attended. The original idea was simple: to hold regular meetings to discuss common problems and experiences, and ways that collectives might help each other.

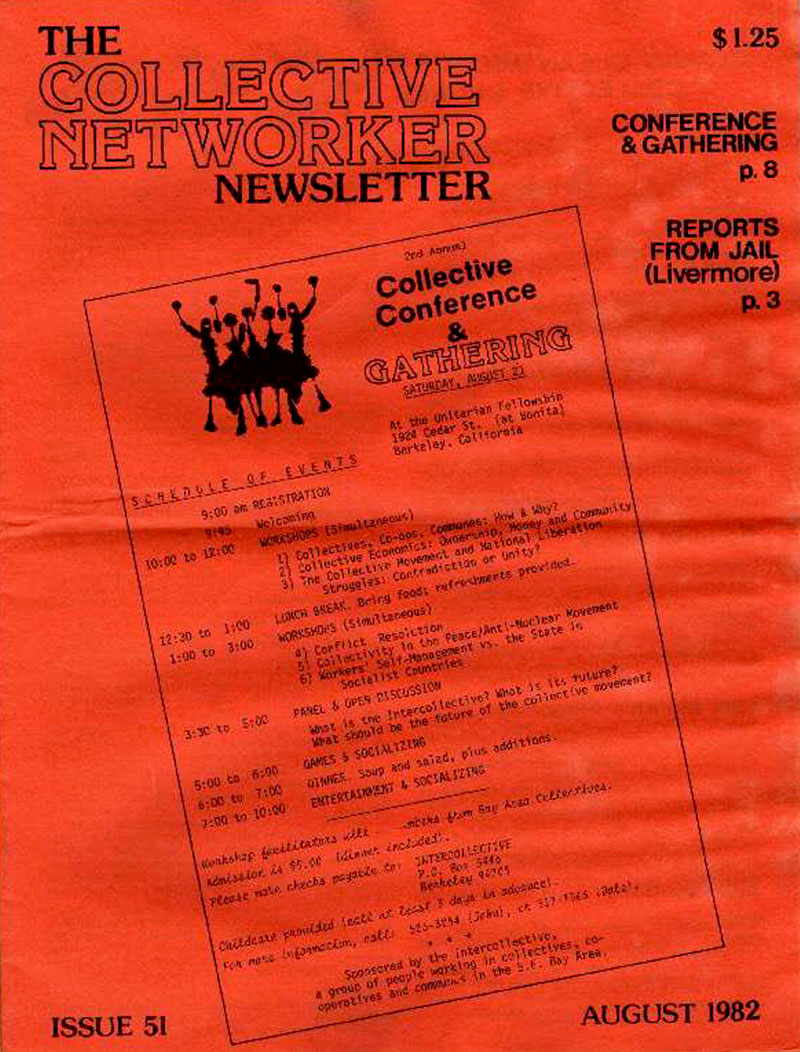

All the members of the Directory Group soon became involved, and the Grapevine began publishing monthly Intercollective minutes and news. It wasn’t long before people from all different types of groups besides food-related collectives began to show up at IC meetings. The Intercollective’s first major project was a conference scheduled for Spring ‘81.

GEOPH: At this same time the Grapevine Network began organizing a series of retreats, mostly at Harbin Hot Springs, where we combined play with networking business. These were very successful. The main focus was on sharing our group living experiences, encouraging participants to offer spontaneous workshops on what they had done or learned by living communally or working collectively, on their personal areas of interest, or to share and brainstorm on their basic needs and resources.

A lot of people showed up, many more than we could ever get to work on the newsletter or to help coordinate the housing meetings. It became clear that there were a lot of interested people out there, people willing to come to events and to support the network, but who were not much interested in doing the organizing work.

JOHN: And the Collective Conference confirmed this, as we had a capacity crowd. After the conference there was a great attendance at Intercollective meetings. People wanted to become more organized. We debated the type of organization we wanted to become, and decided we had to work out a statement of purpose and a decision-making process that we all agreed to.

The struggle over writing these took up a lot of time and energy, and were very frustrating to a lot of people. Most of the same people struggling over the Directory and the Grapevine now started struggling over these. A lot of others who came wanted more practical interaction, not just talking about ideas. They started to drift away, and attendance dropped. But we finally did set up a basic structure in which people could work in autonomous project committees, which would report to the larger group (and to the collective community) in these open monthly meetings.

GEOPH: It was in the fall of that year that the Grapevine problems came to a head. About half of us were totally frustrated with what was happening. It was impossible to be in a process encouraging constant internal struggle, and at the same time meet deadlines which were necessary because of the calendar and housing ads.

Another heated issue was that we defined ourselves as an "open collective". To some of us this meant we were "open" to all ideas, that we encouraged participation and feedback from anyone involved or interested in the broader community. To the advocates of internal struggle, being "open" meant that anybody who wanted to be involved, could be involved. If somebody showed up at production they had to be plugged in.

The less radical faction, I’d say the more practical faction, wanted a group in which a new person had to establish a track record before having a full say and jumping into the middle of production. We wanted to know who was a member of the group and who wasn’t, and wanted members who could be depended on. It felt like we weren’t really able to move forward, as though at each meeting we were always reinventing the wheel.

So six of us decided we’d had enough of it. What we wanted was to do a monthly, focused around the housing and calendar stuff, along with a few articles. The people in the other group wanted to do a major publication of at least twenty-four pages, and they-began talking about doing a quarterly instead of a monthly so that they could really get into the issues of self- management and social change.

The six of us decided to split off and do our own project. The remaining group was obviously against the idea of splitting, but could do nothing to stop us. They questioned whether we even had the right to split off and start a new group. We agreed they could keep the name of Grapevine for their quarterly, and we’d take a new name. We did take the questionable step of continuing the issue numbers from the old Grapevine series — the first Collective Networker (December 1981) read: "Issue 43... Formerly Part of the Grapevine." We felt we deserved at least that continuity, since we were taking over the monthly calendar, housing referrals, and subscription list. We gave subscribers a choice of remaining with either or both publications. The quarterly, however, never came out.

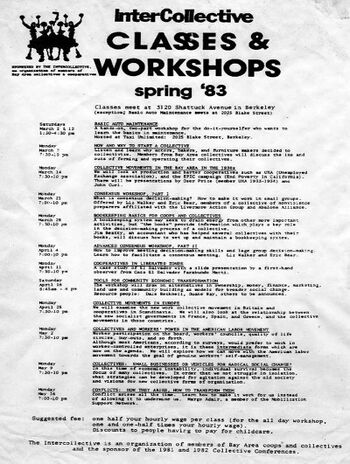

JOHN: The Intercollective hit a low period that winter. Attendance at monthly meetings dropped to a small core group, but that group decided to plan a second conference, which ended up being just as successful as the first. It led to two more main projects: a weekly class and workshop series planned for Spring ‘83, and a new edition of the Directory, now sponsored by the Intercollective. The "internal struggle" advocates, who had pretty much dropped out by that time, were drawn back in by the prospect of doing a new directory.

Some of the old conflicts began immediately. We decided to have a mediation, and brought in two experienced, community-oriented mediators to facilitate this at an open meeting — Margo Adair and Starhawk. They did a great job helping us resolve the negative charge — enough to come out with a small edition of updated listings, including for the first time some west coast out-of-town and out-of-state listings. It also included a promise of a forthcoming larger edition, and solicited articles and descriptive paragraphs about each collective (to be included with the listings).

Well, it took a second mediation before we were able to put out the 1984 Directory, and it was listings only... no articles. The 1985-'86 edition was perfect bound, with 201 Bay Area groups, 65 other California collectives, and 71 between Oregon and Alaska — and with six articles. It was, brought out, I am happy to say, by most of those same people, almost harmoniously. The mediation was a success.

In the interim, the Intercollective did some events that were really exciting, like the workshop/class series, the Collectives Fair, last year’s Co-op Harvest Fair, and two campout retreats. These brought people together from the collectives and the broader community, to have fun, to celebrate the desire to be an alternative, to exchange information and to develop the network.

Between the major events almost all we’ve had going have been the open monthly meetings, which aren’t for everyone. Talk and business.

GEOPH: I know. When attendance dwindles, it’s easy to get discouraged. We forget that most people aren’t willing to sit through meetings, that they’d rather spend their time actually doing something. Yet every time we get an event together, the attendance is great... the interest and support is really there.

A similar situation had existed with the Networker. There had been many times in the past four years when the work tended to fall in my lap — I was the only person really willing to put in the extra work to make it come out on time, if at all.

But over the past year a more solid collective has materialized. Responsibility is being divided better, and collectively delegated. The people who have come in have been more insistent on collective process (hooray!) which has been helpful in creating guidelines and an operations manual so that all the information of the production details isn’t locked up in one person’s head. We’re still needing more "solid" members on our staff, but we’ve made definite progress.

JOHN: Now the Intercollective is going through another period of change.

GEOPH: All in all, it’s pretty exciting to be in the midst of things here in the Bay Area. Seems like every day I run across a new group or a new project that addresses some important issue, that solves a new piece of the puzzle. There’s still loads of work to be done, but look how far we’ve come....