Television invented in San Francisco!?: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(added new image) |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | |||

''by Art Peterson'' | |||

[[Image:CoverTv.jpg]] | |||

[[Image:norbeach$philo-t-farnsworth-photo.jpg]] | [[Image:norbeach$philo-t-farnsworth-photo.jpg]] | ||

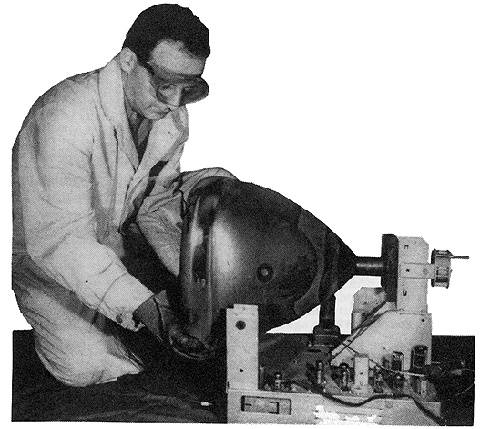

'''Philo T. Farnsworth at work.''' | '''Philo T. Farnsworth at work.''' | ||

<font size=4>The Edison of Green Street: How a 21-Year-Old Genius Invented the Television—In the Shadow of Telegraph Hill</font size> | |||

It may be just a book blurb but those of us who live on Telegraph Hill have reason to take notice. On the back cover of Even Schwartz’s recent biography of Philo T. Farnsworth, Walter Issacson, the chairman of CNN, calls Farnsworth “probably the most influential unknown person in the past century.” | |||

The basis for this claim springs from the work that Farnsworth did at 202 Green Street, at the corner of Sansome. On September 7, 1927, 75 years ago this month, Farnsworth invented television. When Farnsworth began his work a year earlier he was 21 years old, roughly the age of many of the skateboarders one sees performing in front of the Waterfront restaurant these days. By the time Farnsworth came to the neighborhood, he had been carrying his television idea around for seven years. At 14, plowing his father’s potato field in Idaho, he noticed the furrows lined up in neat parallel rows. For the rest of us a furrow is a furrow is a furrow, but the young Farnsworth saw something else. He saw the furrows as lines in a picture that could be broken down, transmitted, then reassembled into a complete picture. Just like television. | |||

This idea became his life. He married at 20 and on his wedding night said to his wife Elma, who was known as Pem: “Pemmie, I have to tell you. There is another woman in my life and her | |||

name is television.” | |||

Farnsworth’s break came when, while working as a temp for the Community Chest in Utah, he met George Everson, a successful fundraiser and Californian. Everson understood that Farnsworth was onto something. Using his San Francisco connections, he arranged to get Farnsworth $25,000 in funding through the Crocker Bank as well as use of the Green Street “laboratory.” Meeting Farnsworth for the first time, Crocker’s Roy Bishop told the young man, “This is the first time anyone has come into this room and got anything out of us without laying something on the table for it.” | |||

<font size=4>Green Street Genesis</font size> | |||

Farnsworth was disappointed when, visiting his laboratory for the first time, discovered it was far from the state-of-the-art facility he had been expecting. 202 Green, known as the Giusti Building after the owner of the carpentry shop on the ground floor, also housed a ground-level garage. Farnsworth was to occupy the upper floor, an area of 600 square feet with a raftered ceiling. | |||

[[Image:Farnsworth-historic-plaque-and-building 6972.jpg]] | |||

'''Historic marker outside the 202 Green Street building.''' | |||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | |||

Location was also a problem. Farnsworth had anticipated a space near the top of Telegraph Hill, where he could conduct his work free of interfering power lines. Instead, the Green Street building abutted the very bottom of the hill, where there was always a danger of rock slides. David Myrick describes one slide in February 1927 in which “rock and earth plunged from Calhoun Terrace, carrying along small sheds, chicken houses and fences.” But, except for a few broken windows, the lab was unharmed. | |||

Farnsworth and Pem, along with Pem’s brother, Cliff Gardner, who came to work for Farnsworth, settled briefly in Berkeley, taking the ferry each day to San Francisco. But the commute was taking up to three hours a day so they soon moved to Vallejo Street on the west side of Telegraph Hill. Farnsworth bought a dilapidated Maxwell touring car to shorten the distance to work. One night, Farnsworth discovered he was out of gas, but this was a mere trifle for a man with his talents. He simply went back into the lab, mixed up a concoction of alcohol and ether, filled the tank and drove home. | |||

Except for the skylights that still grace the building, Farnsworth’s work space, with its rigged electric fittings and wooden braces, was a primitive affair, looking as much like Dr. Frankenstein’s secret lab as anything else. But Farnsworth and his crew, which now included Pem, forged ahead. Then came that September day in 1927 when Farnsworth was able to transmit an image from one room—containing his “dissector unit” — to another, where the image was received on a blue screen. “That’s it folks,” he said, “There you have electronic television.” | |||

[[Image:Farnsworth 01.jpg]] | |||

'''Philo T. Farnsworth and his invention''' | |||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | |||

These embryonic beginnings, however, left Farnsworth a long way from producing a marketable product. His backers, who by this time had invested far more than their initial $25,000, were getting nervous. One day, James Fagan, one of the money men, showed up at Green Street asking for a demonstration. “When are we going to see the dollars in this thing?” he wanted to know. As if on cue, Cliff Gardner slid an image in front of the image detector in one room and on the glowing blue screen in the adjoining room appeared a thick black dollar sign. Fagan could see his dollars. | |||

By 1929, Farnsworth was [[Philo Farnsworth and the Invention of Electronic Television|transmitting visual signals]] as far the as the Hobart building, a mile from the lab. But the investors were feeling the crunch. “It will take a pile of money as high as Telegraph Hill to pull this off,” one of them said. There was talk of selling off Farnsworth’s patents to a large electronics company. | |||

<font size=4>Sarnoff Steals the Show</font size> | |||

Meanwhile, word of Farnsworth’s work had leaked out, attracting prominent visitors to Green Street. In 1930, the radio pioneers Guglielmo Marconi and Lee De Forest visited the lab. They were followed by actress Mary Pickford and her husband Douglas Fairbanks Sr. | |||

The couple, along with Charlie Chaplin, had recently formed United Artists Studios and wanted to find out about this new phenomenon that could send their venture in a different direction. Farnsworth’s most important visitor however, was not well known. He was Vladimir Zworkin, another television pioneer, whose own work led to a dead end. At the time of his visit, however, Zworkin was employed by David Sarnoff, the president of RCA who himself was obsessed with winning the race to turn television into a marketable product. | |||

Farnsworth, believing that all his patents were protected, welcomed Zworkin as a fellow scientist, demonstrating his entire bag of tricks. Zworkin was mightily impressed, so it should come as no surprise that in 1931 the impeccably dressed David Sarnoff himself came knocking on the door at Green Street. Farnsworth was out of town, so his old patron, George Everson, conducted the demonstration. What Sarnoff saw was much closer to a marketable product than anything he had on the drawing boards. But Sarnoff left Green Street saying, “There’s nothing here we’ll need.” | |||

Sarnoff later offered Farnsworth $100,000 for his patents. Farnsworth rejected the offer, not only because it was a puny sum considering what he had to sell, but because like his role model Thomas Edison, he did not want to sell his patents. What he wanted was to establish a licensing agreement with RCA. But Sarnoff was not interested in licensing agreements; he wanted to own the rights. | |||

By late 1931, the Green Street operation was bleeding red ink. It was so bad that Farnsworth and his employees, which by now included Russell Varian, who would go on to become a household name in Silicon Valley, packed up and went to Philadelphia. There, Philco—which was out to beat RCA in the race for a marketable television—set him up in a laboratory. | |||

In 1934, unable to win Farnsworth over, Sarnoff and RCA challenged all 14 of his patents. In every case the U.S. Patent Office ruled in Farnsworth’s favor. RCA finally settled with Farnsworth in 1939, agreeing to pay $1 million for the rights to his main patents. But by then it was too late. Drink and depression were already taking their toll on Philo Farnsworth. He lingered until 1971, dying flat broke and largely forgotten. | |||

The current tenant at 202 Green Street, Philo Television, is a post-production TV company specializing in corporate videos and infomercials. Farnsworth’s memory is honored there by the naming of various editing rooms after people close to him. There is a Cliff Room and an Elma Room. The only other reminder that Farnsworth ever worked there is a charred beam which survived a 1930 fire that destroyed much of what Farnsworth was working on. As it turned out, the building and its contents were fully insured. It was one of Farnsworth’s few lucky breaks. | |||

''—Art Peterson'' (originally published in [http://www.thd.org/semaphorearchives.html The Semaphore] #161, Fall 2002) | |||

'''Bibliography''' | |||

Myrick, David ''San Francisco’ Telegraph Hill'', (San Francisco: City Lights Foundation, 2001) | |||

The | Schwartz, Evan ''The Last Lone Inventor: A Tale of Genius Deceit and the Birth of Television'' (San | ||

Francisco: HarperCollins: 2002) | |||

Stashower, ''Daniel The Boy Genius and The Mogul: The Untold Story of Television'' (New York: Broadway Books, 2002) | |||

[[Jack LaLanne|TV Fitness Pioneer!]] | [[Jack LaLanne|TV Fitness Pioneer!]] | ||

[[ | [[Coit Tower National Historic Site |Prev. Document]] [[The Sentinel Building |Next Document]] | ||

[[category:North Beach]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category: | [[category:North Beach]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:Famous characters]] [[category:Technology]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:06, 26 February 2023

Historical Essay

by Art Peterson

Philo T. Farnsworth at work.

The Edison of Green Street: How a 21-Year-Old Genius Invented the Television—In the Shadow of Telegraph Hill

It may be just a book blurb but those of us who live on Telegraph Hill have reason to take notice. On the back cover of Even Schwartz’s recent biography of Philo T. Farnsworth, Walter Issacson, the chairman of CNN, calls Farnsworth “probably the most influential unknown person in the past century.”

The basis for this claim springs from the work that Farnsworth did at 202 Green Street, at the corner of Sansome. On September 7, 1927, 75 years ago this month, Farnsworth invented television. When Farnsworth began his work a year earlier he was 21 years old, roughly the age of many of the skateboarders one sees performing in front of the Waterfront restaurant these days. By the time Farnsworth came to the neighborhood, he had been carrying his television idea around for seven years. At 14, plowing his father’s potato field in Idaho, he noticed the furrows lined up in neat parallel rows. For the rest of us a furrow is a furrow is a furrow, but the young Farnsworth saw something else. He saw the furrows as lines in a picture that could be broken down, transmitted, then reassembled into a complete picture. Just like television.

This idea became his life. He married at 20 and on his wedding night said to his wife Elma, who was known as Pem: “Pemmie, I have to tell you. There is another woman in my life and her name is television.”

Farnsworth’s break came when, while working as a temp for the Community Chest in Utah, he met George Everson, a successful fundraiser and Californian. Everson understood that Farnsworth was onto something. Using his San Francisco connections, he arranged to get Farnsworth $25,000 in funding through the Crocker Bank as well as use of the Green Street “laboratory.” Meeting Farnsworth for the first time, Crocker’s Roy Bishop told the young man, “This is the first time anyone has come into this room and got anything out of us without laying something on the table for it.”

Green Street Genesis

Farnsworth was disappointed when, visiting his laboratory for the first time, discovered it was far from the state-of-the-art facility he had been expecting. 202 Green, known as the Giusti Building after the owner of the carpentry shop on the ground floor, also housed a ground-level garage. Farnsworth was to occupy the upper floor, an area of 600 square feet with a raftered ceiling.

Historic marker outside the 202 Green Street building.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Location was also a problem. Farnsworth had anticipated a space near the top of Telegraph Hill, where he could conduct his work free of interfering power lines. Instead, the Green Street building abutted the very bottom of the hill, where there was always a danger of rock slides. David Myrick describes one slide in February 1927 in which “rock and earth plunged from Calhoun Terrace, carrying along small sheds, chicken houses and fences.” But, except for a few broken windows, the lab was unharmed.

Farnsworth and Pem, along with Pem’s brother, Cliff Gardner, who came to work for Farnsworth, settled briefly in Berkeley, taking the ferry each day to San Francisco. But the commute was taking up to three hours a day so they soon moved to Vallejo Street on the west side of Telegraph Hill. Farnsworth bought a dilapidated Maxwell touring car to shorten the distance to work. One night, Farnsworth discovered he was out of gas, but this was a mere trifle for a man with his talents. He simply went back into the lab, mixed up a concoction of alcohol and ether, filled the tank and drove home.

Except for the skylights that still grace the building, Farnsworth’s work space, with its rigged electric fittings and wooden braces, was a primitive affair, looking as much like Dr. Frankenstein’s secret lab as anything else. But Farnsworth and his crew, which now included Pem, forged ahead. Then came that September day in 1927 when Farnsworth was able to transmit an image from one room—containing his “dissector unit” — to another, where the image was received on a blue screen. “That’s it folks,” he said, “There you have electronic television.”

Philo T. Farnsworth and his invention

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

These embryonic beginnings, however, left Farnsworth a long way from producing a marketable product. His backers, who by this time had invested far more than their initial $25,000, were getting nervous. One day, James Fagan, one of the money men, showed up at Green Street asking for a demonstration. “When are we going to see the dollars in this thing?” he wanted to know. As if on cue, Cliff Gardner slid an image in front of the image detector in one room and on the glowing blue screen in the adjoining room appeared a thick black dollar sign. Fagan could see his dollars.

By 1929, Farnsworth was transmitting visual signals as far the as the Hobart building, a mile from the lab. But the investors were feeling the crunch. “It will take a pile of money as high as Telegraph Hill to pull this off,” one of them said. There was talk of selling off Farnsworth’s patents to a large electronics company.

Sarnoff Steals the Show

Meanwhile, word of Farnsworth’s work had leaked out, attracting prominent visitors to Green Street. In 1930, the radio pioneers Guglielmo Marconi and Lee De Forest visited the lab. They were followed by actress Mary Pickford and her husband Douglas Fairbanks Sr.

The couple, along with Charlie Chaplin, had recently formed United Artists Studios and wanted to find out about this new phenomenon that could send their venture in a different direction. Farnsworth’s most important visitor however, was not well known. He was Vladimir Zworkin, another television pioneer, whose own work led to a dead end. At the time of his visit, however, Zworkin was employed by David Sarnoff, the president of RCA who himself was obsessed with winning the race to turn television into a marketable product.

Farnsworth, believing that all his patents were protected, welcomed Zworkin as a fellow scientist, demonstrating his entire bag of tricks. Zworkin was mightily impressed, so it should come as no surprise that in 1931 the impeccably dressed David Sarnoff himself came knocking on the door at Green Street. Farnsworth was out of town, so his old patron, George Everson, conducted the demonstration. What Sarnoff saw was much closer to a marketable product than anything he had on the drawing boards. But Sarnoff left Green Street saying, “There’s nothing here we’ll need.”

Sarnoff later offered Farnsworth $100,000 for his patents. Farnsworth rejected the offer, not only because it was a puny sum considering what he had to sell, but because like his role model Thomas Edison, he did not want to sell his patents. What he wanted was to establish a licensing agreement with RCA. But Sarnoff was not interested in licensing agreements; he wanted to own the rights.

By late 1931, the Green Street operation was bleeding red ink. It was so bad that Farnsworth and his employees, which by now included Russell Varian, who would go on to become a household name in Silicon Valley, packed up and went to Philadelphia. There, Philco—which was out to beat RCA in the race for a marketable television—set him up in a laboratory.

In 1934, unable to win Farnsworth over, Sarnoff and RCA challenged all 14 of his patents. In every case the U.S. Patent Office ruled in Farnsworth’s favor. RCA finally settled with Farnsworth in 1939, agreeing to pay $1 million for the rights to his main patents. But by then it was too late. Drink and depression were already taking their toll on Philo Farnsworth. He lingered until 1971, dying flat broke and largely forgotten.

The current tenant at 202 Green Street, Philo Television, is a post-production TV company specializing in corporate videos and infomercials. Farnsworth’s memory is honored there by the naming of various editing rooms after people close to him. There is a Cliff Room and an Elma Room. The only other reminder that Farnsworth ever worked there is a charred beam which survived a 1930 fire that destroyed much of what Farnsworth was working on. As it turned out, the building and its contents were fully insured. It was one of Farnsworth’s few lucky breaks.

—Art Peterson (originally published in The Semaphore #161, Fall 2002)

Bibliography

Myrick, David San Francisco’ Telegraph Hill, (San Francisco: City Lights Foundation, 2001)

Schwartz, Evan The Last Lone Inventor: A Tale of Genius Deceit and the Birth of Television (San Francisco: HarperCollins: 2002)

Stashower, Daniel The Boy Genius and The Mogul: The Untold Story of Television (New York: Broadway Books, 2002)