Gratitude for Nail House in Diamond Heights: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>I was there . . .</font></font> </font>''' ''by Fernando Martí, November 2022'' ''Originally published at [htt...") |

m (Protected "Gratitude for Nail House in Diamond Heights" ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite))) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 13:05, 5 December 2022

I was there . . .

by Fernando Martí, November 2022

Originally published at Justseeds

Nail House in Luoyang, Henan province, China, in middle of new roadway.

Photo: Creative Commons, via boingboing.net

We think sometimes that cities are defined by their castles and towers, their highways and skyscrapers. But they are also defined by their exceptions: their nail houses and holdouts, scavenged gardens and squatted apartments, spaces carved out in opposition to the forces of state and capital that create ever-taller monuments to marketing brands and to the conformity of aggregated “units.” Against seemingly overwhelming pressure from developers and bureaucracies to buy up or evict and redevelop entire areas, there are always those who hold out: a farm in the middle of Narita Airport in Tokyo, simple holdout houses dwarfed by towers from Manhattan to Washington DC to Seattle, or nail houses amidst the explosive urbanization of state-capital China.

Nail houses: supposedly named for nails that get stuck in the wood. They can’t be pounded in, and they can’t be pulled out. This isn’t a function of the nail, or the hammer. It’s the wood, the ground, that holds on and refuses to let go. It’s a relationship that may have begun violently, like the initial colonization and settlement that created our cities, but is now inseparable. These are fights as old as the enclosures of the commons, or older, as old as the first accumulation of properties by the lords of land. And as everyday as every eviction where a tenant refuses to go quietly into the night.

In Albuquerque, our friend Marisol takes us to her old haunts in Barelas, to the Hispanic Cultural Center’s tree-shaded parking lot to show us the house where Adela Martinez died, tucked away under the massive stucco walls of the fortress-like Cultural Center. This corner of Barelas was planned for destruction by the powers of urban renewal in the 1970s, when the city leaders envisaged an industrial park (jobs for the community!); then in the 1990s, in the name of cultural preservation, the city used its powers of eminent domain to evict the remaining Hispanic families. Ah, the irony. But Adela held out, fought back, and sued. Her son Orlando Lujan Martinez recounted that she would say “No, a million dollars is not enough. Not now, not ever…” Her house is still there, and her family remains, hanging on generation by generation, living culture under the shadow of official “Culture.”

Adela Martinez house, Albuquerque

Photo: Fernando Martí

Here in San Francisco, I often bike past a two-story Victorian on 12th and Folsom, dwarfed by two massive new South of Market developments on either side. I don’t know if this was a neighbor who held out against the developers offers, or a property owned by a trust that couldn’t make a decision, or simply passed over by developers. It sits as a reminder on my rides to the faceless Mission Bay and Transbay Redevelopment Areas that the “urban renewal” of our cities is uneven and contradictory, that little houses, like the people that occupy them, will survive even in the face of catastrophic change from above.

12th Street Victorian in the shadow of its neighbors.

Image: courtesy Fernando Martí

These fights are more than about preserving a particular physical relic frozen in amber, but about the lives for which those objects were a vessel. They are the reenactments of ages-old struggles of two world views: the incremental development of communities driven by the agency, the loves and desires and hopes of the individuals who make up those communities; and an opposing world view of real estate development driven by the capitalists and the planners and policy-makers who, whether with intention or not, serve as their tools.

Now my family will be part of one of those stories. Two weeks ago we finally got the email we had been waiting for for five months: that we were “conditionally approved” (pending a new income certification next year) for an affordable apartment in an 8-unit building under construction in Diamond Heights. When the Victorian we had lived in for twenty-four years was sold, and the inevitable eviction papers were served, we put up a fight to stay. We kept the fight up for three years, through house sales and organizing, through the pandemic and shelter-in-place, through demonstrations and lawyering (thank you SF’s tenant right to counsel). We knew we were lucky even as we faced what every tenant fears: we were lucky that we knew we would land on our feet, even if we had to leave the city that had become unaffordable to most of the people we knew. The entire working class of San Francisco would be gone now, if not for the victories of rent control and funding for affordable housing. This city was the community we knew, that had nurtured us as organizers and artists; we believed, in Henri Lefebvre’s phrase, that we had “a right to the city,” because we were part of making it what it was. As we read the writing on the wall, the unfairness of the laws that allowed a landowner to evict a tenant who had always paid their rent on time, we began to look at affordable housing options, what we qualified on our nonprofit/artist incomes, and how the misfortune of our eviction could give us a “displaced tenant preference” on the housing lotteries.

In May, right around my birthday, we got in the lottery for this Diamond Heights building: we were one of five households applying with an eviction preference for one of the units; in total there were 466 applicants who lived or worked in SF who applied for the 8 units. Every time I think of that lottery, I think of the other four evicted households who applied at the same time as us, and the other 460 households still searching for housing in the city. Over the next year our family and friends will be will be helping construct the Habitat for Humanity building, putting our sweat equity into it. It’s a sweet full-circle, as my graduate school thesis was a proposal for high-density low-rise sweat equity housing in San Francisco, just like this project. But the history of this particular site hits me at a deeper level: the only reason this little lot, surrounded by condo buildings and $2 million Eichlers, would even be affordable housing is the tenaciousness of people who refused to give in to the Redevelopment bulldozers. Like the owners of the nail houses in China, the farmers at Narita, or Adela Martinez in Albuquerque, they hold out, and in the process maintain the human face and histories of their neighborhoods.

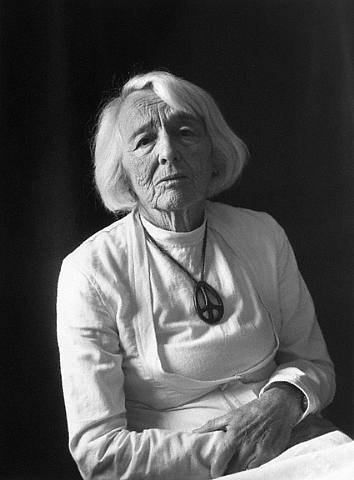

Maria “Mitzi” Kolisch

Photo: Imogen Cunningham

Maria “Mitzi” Kolisch was an artist, activist and medical researcher from Vienna whose family emigrated to escape the Nazis before World War II. She taught in the Physics Department at UCLA, lost her job when she refused to sign McCarthy’s loyalty oaths, and moved to the ferment of SF in the 50s. She bought a little farmhouse in the Diamond Heights hills, built herself an artist’s studio, and entertained there a circle of avant-garde friends, people like Imogen Cunningham, Ruth Asawa, George Gershwin, Linus Pauling, and Bucky Fuller. The echoes of their gatherings still resonate on the hillside.

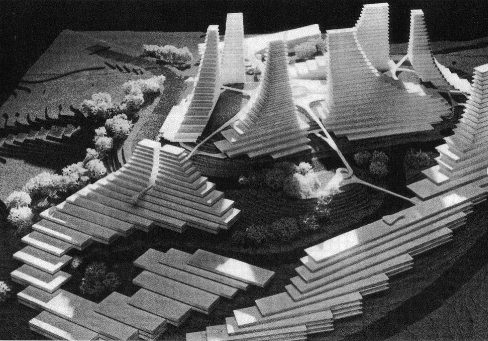

When San Francisco’s first Redevelopment Agency came with their bulldozers in the early 60s with plans for a hillside full of luxury condos and single-family homes, she held on. The [[Diamond Heights}Diamond Heights Redevelopment Plan Area]] became the model for the other redevelopment areas of the city that blazed their destruction through the 60s and 70s, destroying the city’s produce district along the Embarcadero, the SROs filled with veteran longshoremen in South of Market, and the Black neighborhoods of the Western Addition (and almost the Mission District as well). To take the land, whether by the residents’ choice or by eminent domain, the Agency had to claim that the 158 houses and 636 parcels on the hillside were “blighted.” The Redevelopment Agency wrote that Diamond Heights was “presently a predominantly open, blighted area, characterized by… economic disuse; faulty planning; the subdividing and sale of lots of irregular form and shape and inadequate size for proper usefulness and development; the laying out of lots in disregard to the contours and other physical characteristics of the ground and surrounding conditions; the existence of inadequate streets, open spaces and utilities; economic maladjustment to such an extent that the capacity to pay taxes is reduced and tax receipts are inadequate for the cost of public services rendered; and lack of proper utilization of area, resulting in a stagnant and unproductive condition of land potentially useful and valuable.” Elsewhere they wrote: “In land hungry, house hungry San Francisco very little other vacant land remains. It seems apparent, then, that the Diamond Heights area is one of ‘arrested development.’” The residents sued to stay or to be able to relocate back to their homes, but the California Supreme Court upheld the Agency’s position.

SF Redevelopment Agency unbuilt competition proposal for highrises on Diamond Heights

Image: courtesy Fernando Martí

Maria Kolisch was among those who fought back – and “fought like a tiger,” according to her son. Somehow she was able to stay. Her little cottage and art studio were among the few things left on the hillside from before Redevelopment.

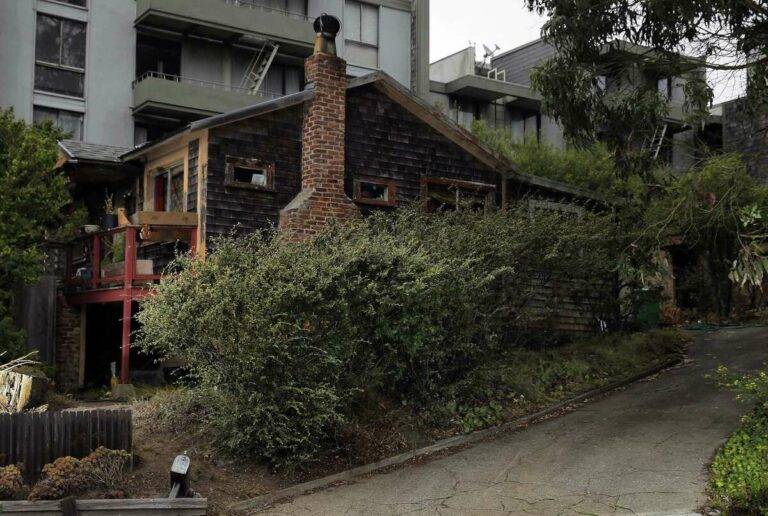

But she was not antidevelopment. Her vision was to give the land away for something other than luxury condos – initially homes for transitional aged youth, which she was working on when she passed away in 1987. Her son Mischa Seligman, in his 90s, continued to work on plans for affordable housing on the site. Ironically, even most nonprofits couldn’t get financing, despite the offer of free land, because lenders refused to finance a property with legally binding deed restrictions for permanent affordability. And the Mayor’s Office of Housing rarely funds anything smaller than 100 units – let alone a modest 6,500 s.f. odd-shaped lot on a hillside. Finally, after an article came out in the Chronicle about a man who couldn’t give away his house, Habitat got interested.

Maria Kolisch’s cottage at 36 Amber, before being demolished to build affordable housing.

Photo: Carlos Avila Gonzalez, The Chronicle

Now there’s an eight-unit first-time homeowner development under construction on Maria Kolisch’s little parcel that she fought so hard to keep from being turned into luxury condos. Remembering and forgetting history is a funny thing – used to justify one political story or another. The Mayor’s press release mentions simply that “In the 1950s, Maria was one of the first residents of the newly created Diamond Heights neighborhood.”

I feel lucky, blessed, to know we’ll finally have some stability in our home. But all our luck and blessings are built on what others have done: the activists who fought for rent control and eviction protections and condo conversion moratoriums, and the holdouts and nail houses who show us the way and create the opportunities for future generations to stay in their city.