Bike the Bridge Coalition: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

<font size=4>Introduction</font><br /> | <font size=4>Introduction</font><br /> | ||

The pathway which would become the biggest bike-related expenditure in the history of the Bay Area was not expected to happen. In 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake had damaged the eastern span of the Bay Bridge, and seven years later, the decision had finally been made to demolish the old bridge. The cost of replacing the span had already quadrupled from initial estimates, and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) had voted 22-0 against including a bike path in the project. But a small band of activists willing to put their bodies on the line found a way to change the conversation through direct action. | The pathway which would become the biggest bike-related expenditure in the history of the Bay Area was not expected to happen. In 1989, the [[Loma Prieta Earthquake, 1989|Loma Prieta earthquake]] had damaged the eastern span of the [[Bay Bridge Artery|Bay Bridge]], and seven years later, the decision had finally been made to demolish the old bridge. The cost of replacing the span had already quadrupled from initial estimates, and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) had voted 22-0 against including a bike path in the project. But a small band of activists willing to put their bodies on the line found a way to change the conversation through direct action. | ||

<font size=4>Background</font><br /> | <font size=4>Background</font><br /> | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

Meggs and others passed out flyers advertising BTBC at Critical Mass rides, set up a web site for the group, and began publishing a zine, the ''Bike the Bridge Bugle'', to document their efforts. CalTrans and the CHP largely allowed these demonstrations to go on as long as they didn’t get on the bridge itself, although Eisen led a quiet Sunday morning ride from the Richmond side which successfully made the crossing, resulting in possibly the first-ever bike crossing of the North Bay. In February 1997, nine other cyclists entered the Richmond Bridge from the San Rafael side, making it almost to Richmond before being stopped by the CHP and forced to ride back to San Rafael, receiving 18 citations. A protest ride in March 1997 to “free the Richmond 9,” documented in the Bike the Bridge Bugle zine, successfully crossed the entire length of the bridge.[2]<br /> | Meggs and others passed out flyers advertising BTBC at Critical Mass rides, set up a web site for the group, and began publishing a zine, the ''Bike the Bridge Bugle'', to document their efforts. CalTrans and the CHP largely allowed these demonstrations to go on as long as they didn’t get on the bridge itself, although Eisen led a quiet Sunday morning ride from the Richmond side which successfully made the crossing, resulting in possibly the first-ever bike crossing of the North Bay. In February 1997, nine other cyclists entered the Richmond Bridge from the San Rafael side, making it almost to Richmond before being stopped by the CHP and forced to ride back to San Rafael, receiving 18 citations. A protest ride in March 1997 to “free the Richmond 9,” documented in the Bike the Bridge Bugle zine, successfully crossed the entire length of the bridge.[2]<br /> | ||

At the same time, Critical Mass was starting to explode. Tensions between bikes, drivers and the city kept rising, until on July 25, 1997, 5000 cyclists defied Mayor Willie | At the same time, [[Critical Mass|Critical Mass]] was starting to explode. Tensions between bikes, drivers and the city kept rising, until on July 25, 1997, 5000 cyclists defied [[Mayor Willie Brown|Mayor Willie Brown]]’s plan to have an orderly, police-escorted ride, and instead scattered all over the city. Brown, desperate to appear as taking positive action after the debacle, asked Dave Snyder, then head of the SF Bike Coalition, “what do these people want?”[3] A month later, the first San Francisco Bike Plan was approved by the city, and bike advocacy was on its way from marginal to mainstream in the Bay Area. | ||

<font size=4>The Bay Bridge</font><br /> | <font size=4>The Bay Bridge</font><br /> | ||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

A much less expensive option would be to fit the bike lane on the existing roadway. The Bay Bridge road deck is 58’ wide, only 4’ narrower than the six-lane Golden Gate, and the Bay Bridge upper deck handled six lanes of auto traffic when it opened. A bike path could take eight feet of the existing space, leave 10’ lanes for cars, and save hundreds of millions of dollars, though that design may be problematic for pedestrian and wheelchair access.[9] <br /> | A much less expensive option would be to fit the bike lane on the existing roadway. The Bay Bridge road deck is 58’ wide, only 4’ narrower than the six-lane Golden Gate, and the Bay Bridge upper deck handled six lanes of auto traffic when it opened. A bike path could take eight feet of the existing space, leave 10’ lanes for cars, and save hundreds of millions of dollars, though that design may be problematic for pedestrian and wheelchair access.[9] <br /> | ||

[[ | [[Image:San-Rafael-bridge-bike-lane 20210317 002454043.jpg]] | ||

''' | '''Richmond Bridge bike path with movable barrier, 2021.''' <br /> | ||

''Photo: | ''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | ||

On BTBC’s original target, the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge, a design with a moveable barrier providing a two-way bike lane on the road deck is slated for installation by 2018.[11] Before long, there will be connectivity through most of the Bay for bikes for the first time ever, all because of a strong and slightly crazy coalition of planners, advocates, and activists. | On BTBC’s original target, the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge, a design with a moveable barrier providing a two-way bike lane on the road deck is slated for installation by 2018.[11] Before long, there will be connectivity through most of the Bay for bikes for the first time ever, all because of a strong and slightly crazy coalition of planners, advocates, and activists. | ||

<font size=4>Notes:</font size> | |||

[1] Interview with Robert Raburn by author, November 22, 2016. <br /> | [1] Interview with Robert Raburn by author, November 22, 2016. <br /> | ||

Latest revision as of 12:40, 20 October 2022

Historical Essay

by Tom Holub

Bike the Bridge Coalition ride supporting rail on the new bridge

Photo: Jason Meggs, Bike the Bridge Coalition

| After seven years of debate, the decision had been made to replace the Bay Bridge which had been damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. The Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) had voted 22-0 against including a bike path in the project, but a small band of people willing to put their bodies on the line by riding the bridges found a way to change the conversation. A coalition of activists (“door bangers”) and advocates (“hand shakers”) led MTC to reverse their decision, and provide bikes and pedestrians with their first-ever access across the bay. |

Introduction

The pathway which would become the biggest bike-related expenditure in the history of the Bay Area was not expected to happen. In 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake had damaged the eastern span of the Bay Bridge, and seven years later, the decision had finally been made to demolish the old bridge. The cost of replacing the span had already quadrupled from initial estimates, and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) had voted 22-0 against including a bike path in the project. But a small band of activists willing to put their bodies on the line found a way to change the conversation through direct action.

Background

There had never been a legal way to bike from the East Bay into San Francisco or Marin County. The nearest legal bay crossing for bikes was the Dumbarton Bridge, 30 miles to the south. During commute hours, bikes were not allowed on BART, and a CalTrans rush-hour shuttle service was slow and unreliable. As cycling rates rose in the Bay Area during the 1990s, advocates clamored for additional options for bike commuters. At the same time, Critical Mass rides were gaining in popularity (amongst cyclists) and notoriety (amongst drivers), building a large and growing community of bike advocates who were comfortable being at odds with the authorities.

Richmond Bridge “feasibility rides”

In 1996 Jason Meggs, a Critical Mass participant and founder of the Bicycle-Friendly Berkeley Coalition, organized a ride up to the eastern toll plaza of the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge which included over 100 cyclists. The Richmond Bridge includes a breakdown lane along its entire length, so could easily accommodate a bike lane without significant additional infrastructure; it seemed like a more feasible target than the Bay Bridge.

It was possible to ride all the way to the base of the Richmond Bridge on both shorelines, so the rides were doable for bike advocates like Alex Zuckerman, Victoria Eisen, and Robert Raburn who didn’t much want to get arrested, as well as the more activist riders like Jason Meggs and Dave Cohen. The CHP attempted to block the first ride, but the group stayed entirely on bike-legal roads and pathways, and the CHP eventually let them through. Their success led Meggs to form the Bike the Bridge Coalition (BTBC), which would hold these “feasibility rides” every month to advocate for bike access to the bridge. [1]

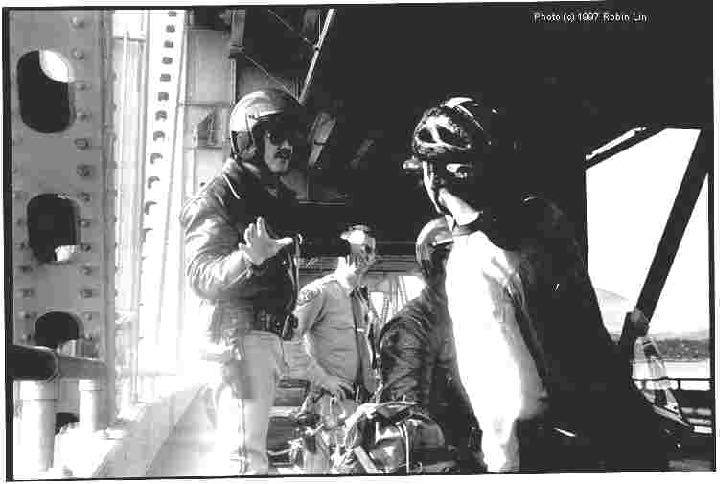

BTBC stopped on the Richmond Bridge

BTBC stopped on the Richmond Bridge

Photo: Robin Lin

Meggs and others passed out flyers advertising BTBC at Critical Mass rides, set up a web site for the group, and began publishing a zine, the Bike the Bridge Bugle, to document their efforts. CalTrans and the CHP largely allowed these demonstrations to go on as long as they didn’t get on the bridge itself, although Eisen led a quiet Sunday morning ride from the Richmond side which successfully made the crossing, resulting in possibly the first-ever bike crossing of the North Bay. In February 1997, nine other cyclists entered the Richmond Bridge from the San Rafael side, making it almost to Richmond before being stopped by the CHP and forced to ride back to San Rafael, receiving 18 citations. A protest ride in March 1997 to “free the Richmond 9,” documented in the Bike the Bridge Bugle zine, successfully crossed the entire length of the bridge.[2]

At the same time, Critical Mass was starting to explode. Tensions between bikes, drivers and the city kept rising, until on July 25, 1997, 5000 cyclists defied Mayor Willie Brown’s plan to have an orderly, police-escorted ride, and instead scattered all over the city. Brown, desperate to appear as taking positive action after the debacle, asked Dave Snyder, then head of the SF Bike Coalition, “what do these people want?”[3] A month later, the first San Francisco Bike Plan was approved by the city, and bike advocacy was on its way from marginal to mainstream in the Bay Area.

The Bay Bridge

So, while BTBC was building a community of advocates with a specific policy goal of bridge access, and while the relative power of cyclists was shifting, the project to rebuild the east span of the Bay Bridge started moving. The initial design concept, published in December 1996, was a simple viaduct which included a bike lane, but not a tower, at a cost estimate of $1.2 billion, compared to a retrofit cost of $915 million to fix the existing bridge. It took another year to finally make the decision to choose replacement over retrofit, by which time the cost estimate had risen to $1.5 billion, and the bike lane had disappeared. Governor Pete Wilson (R-San Diego) laid out the proposal as a choice; CalTrans would build a simple viaduct, and if the Bay Area wanted anything better, they’d have to tax themselves to pay for it. [4]

Because of resistance to CalTrans’ design, which was called a “glorified freeway on-ramp,”[5] the project was handed over to MTC to work out the design elements. According to Raburn, Mary King, MTC’s lead on the project, told him that MTC was considering three amenities for the bridge: a signature tower, a rail line, and a bike path, and that “your path is the one that has the least chance of success.” [1]

Regional Measure 1, a bridge toll approved by voters in 1988, included language requiring all new Bay Area bridges to have bike and pedestrian access. The Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) required “maximum feasible public access” for new projects along the shoreline. BTBC wanted to use that leverage to push for a bike path on the new span. Raburn and Meggs saw the Bay Bridge project as a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” for advocacy, and they knew that if they didn’t get the path into the design that it would never happen. [6]

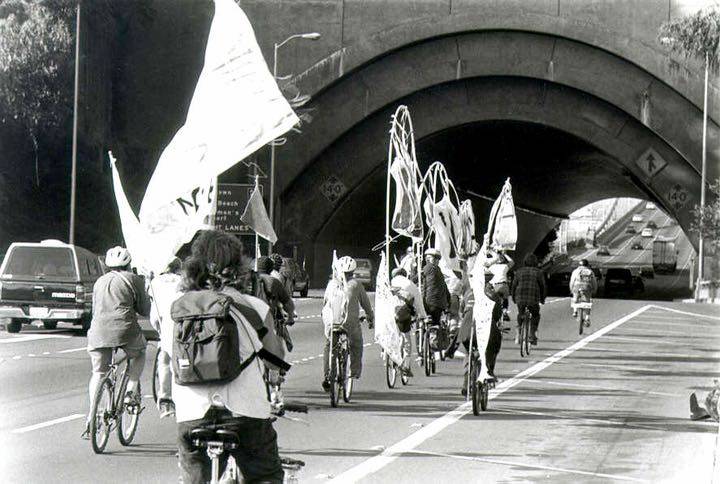

First Bay Bridge ride: BTBC entering the bridge from Burma Road

First Bay Bridge ride: BTBC entering the bridge from Burma Road

Photo: Jason Meggs, Bike the Bridge Coalition

The first publicized bridge ride came on September 10, 1997, coinciding with a BART strike that snarled commutes all over the Bay Area. A group of six riders, led by Meggs, found a way to access an old bus entry to the bridge on Burma Road. Burma Road lacked any signage prohibiting bikes or pedestrians, so their entry to the bridge was technically legal. The group triumphantly made it all the way across, though one rider got her front wheel stuck in the expansion joints between bridge sections. They were arrested and charged with "conspiracy to commit a misdemeanor of crossing the bridge illegally, or with unauthorized vehicles," though the charges later were dropped. Dave Campbell, now advocacy director for Bike East Bay, said that the group came to the next BFBC meeting in their orange prison jumpsuits, giddy over the success.[7]

Possibly because of the evolving status of bike advocacy in the Bay Area, the press surrounding the ride was mostly positive, which energized the movement. The mix of activists and advocates went to work. Meggs said “I was the door-banger; Alex [Zuckerman] was the hand-shaker.”[6] Campbell told Meggs, “I’ll get a bike path to the bridge--you get a bike path on the bridge.”[7] Zuckerman, Raburn, Campbell, and Eisen worked their inside connections with MTC and CalTrans, while Meggs continued to agitate through direct action. Raburn notes, “The word ‘Coalition’ really meant something; it brought together Critical Mass, bike advocates, and lycra riders” to push for a single goal. “It’s on the agenda...let’s go fill out some more speaker cards.” [1]

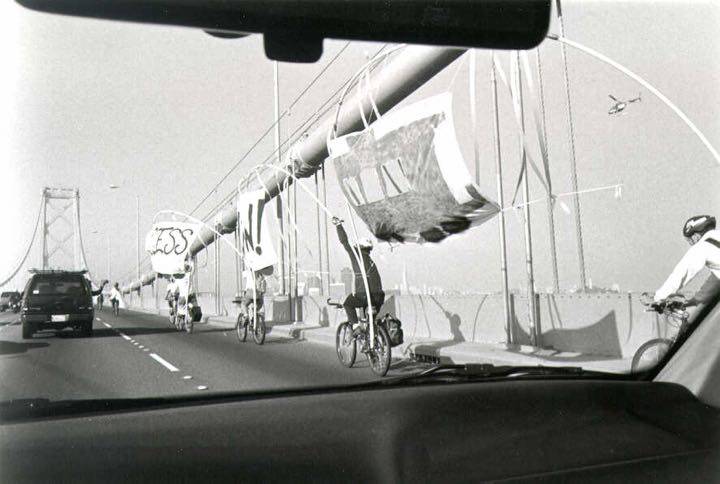

BTBC ride promoting rail on the Bay Bridge

BTBC ride promoting rail on the Bay Bridge

Photo: Jason Meggs, Bike the Bridge Coalition

A year after the initial ride, with project costs still ballooning and little progress being made, BTBC organized another ride, this time to advocate for including both a bike path and rail on the new span. Campbell followed this ride in his pickup truck, keeping the lane clear and filming it, and the CHP response was less friendly this time. The group was stopped on the off-ramp to the Transbay Terminal, blocking bus access from the bridge for some time as they were gender-segregated, handcuffed, and arrested on charges of felony conspiracy to block traffic (later dropped). The men and women sang songs to each other from their jail cells, and Meggs told Campbell, “Today you became a real bike advocate.”[7]

Members of BTBC arrested on the Bay Bridge off-ramp

Members of BTBC arrested on the Bay Bridge off-ramp

Photo: Jason Meggs, Bike the Bridge Coalition

The press for this ride was less favorable, with coverage focusing on the traffic problems ostensibly caused by the protest.[8] Raburn felt at the time that the controversy was a setback; CalTrans had formed the Bicycle/Pedestrian Advisory Committee to work out design issues for the path; it felt like progress was being made, and now EBBC had to do some damage control. Eisen felt that the BTBC’s antics may have been undermining the attempts to work within the system. “It was uncomfortable for us...while we were going to meetings in business clothing, Jason was showing up in one piece spandex suits.”[9] Still, Eisen acknowledges, “they made us look reasonable.”[9] BTBC’s direct action kept the issue in the spotlight, and in late 1998, MTC voted unanimously to approve the new east span, at a cost of $50 million.

Campbell said, “BTBC made all the difference. MTC voted 22-0 against the path at one point, and then 22-0 for it.” Raburn opines, “Jason and Chris (Carlsson, co-founder of Critical Mass) was essential in giving a voice to so many people who weren’t lycra riders. That became a lot of political clout--the ‘heroistic’ aspect of bicycling. They were good players to work with; they created a whole structure without a structure. Mutual respect, and one common goal.” [1]

The Bay Bridge eastern span path

The Bay Bridge eastern span path

Photo: Tom Holub

Biking the Bridge today

The east span Bay Bridge project itself saw years of delays and cost overruns (eventually costing over $6 billion), and the bike path took even longer. A partial path was opened in 2015, but removal of the old bridge, and other construction concerns kept it from being connected to Yerba Buena Island for some time. Finally, in October 2016, just over 20 years after the foundation of BTBC, the Alex Zuckerman Bike Path opened, and for the first time it became possible to legally ride a bridge from the East Bay towards San Francisco. The hours are still limited by construction, and there is no (legal) way to ride to San Francisco from Treasure Island, but BTBC is still at work. In February 2010, State Senator Loni Hancock introduced a bill to allow the Bay Area Toll Authority to use toll revenues to pay for a path on the western span.[10]

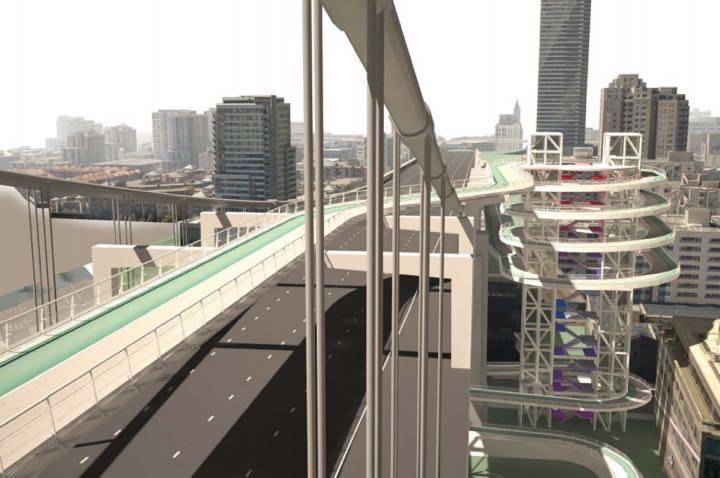

Conceptual design for western span bike path ramp

Conceptual design for western span bike path ramp

Photo: San Francisco Bike Coalition

MTC is evaluating the options, which face a number of engineering challenges, especially with the touchdown on the San Francisco side, where the bridge is over 160’ above ground at landfall. Spiralling ramps down to the waterfront are projected to cost in the hundreds of millions of dollars. But Eisen believes that there is enough momentum that the west span path “is just a matter of time.”[9] As Campbell puts it, “That’s a $1 bridge toll for 3 years. Can you sit here with your grandchildren and tell them it was a bad idea to spend that money?”[7]

A much less expensive option would be to fit the bike lane on the existing roadway. The Bay Bridge road deck is 58’ wide, only 4’ narrower than the six-lane Golden Gate, and the Bay Bridge upper deck handled six lanes of auto traffic when it opened. A bike path could take eight feet of the existing space, leave 10’ lanes for cars, and save hundreds of millions of dollars, though that design may be problematic for pedestrian and wheelchair access.[9]

Richmond Bridge bike path with movable barrier, 2021.

Richmond Bridge bike path with movable barrier, 2021.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

On BTBC’s original target, the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge, a design with a moveable barrier providing a two-way bike lane on the road deck is slated for installation by 2018.[11] Before long, there will be connectivity through most of the Bay for bikes for the first time ever, all because of a strong and slightly crazy coalition of planners, advocates, and activists.

Notes:

[1] Interview with Robert Raburn by author, November 22, 2016.

[2] Meggs, Jason, 1997. “Bike the Bridge Bugle Newsletter #2.” April, 1997.

[3] Interview with Dave Snyder by author, September 30, 2015

[4] Frick, Karen Trapenberg. 2016. Remaking the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge : A Case of Shadowboxing with Nature.Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire ; New York, NY : Routledge, 2016.

[4] Lucas, Greg. "New Year Bringing Higher Tolls to Bay Area Bridges / Fee Will Double to $2 on State-Owned Spans." SFGate., last modified 1997-12-26, accessed Dec 16, 2016.

[4] Interview with Dave Campbell by author, November 15, 2016

[6] Interview with Jason Meggs by author, November 16, 2016

[7] Interview with Dave Campbell by author, November 15, 2016

[8] Delgado, Ray. "Bicycle Protest Snarls Commute on Bay Bridge." SFGate., last modified September 10, accessed September 22, 2016.

[9] Interview with Victoria Eisen by author, January 13, 2017

[10] Goebel, Bryan, “Hancock Introduces Bill to Allow Toll Funds for Bay Bridge Bike Path”, StreesblogSF, February 22, 2010.

[11] Metropolitan Transportation Commission, “Richmond-San Rafael Bridge Bike/Pedestrian Path Project”, MTC, accessed February 20, 2017.