Bay Bridge for Everyone: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' ''by Cycle-Analysts for Fair Access, 2012'' Next year [2013] the new...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

[[category:Bridges]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:transit]] [[category:2010s]] [[category: | [[category:Bridges]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:transit]] [[category:2010s]] [[category:Bicycling]] | ||

Revision as of 12:18, 20 October 2022

Historical Essay

by Cycle-Analysts for Fair Access, 2012

Next year [2013] the new east span of the Bay Bridge will open. Thanks to the diligent and dogged efforts of cyclists and sustainable transport advocates in the 1990s, Caltrans was required to build a bike-and-pedestrian path as part of the new structure.

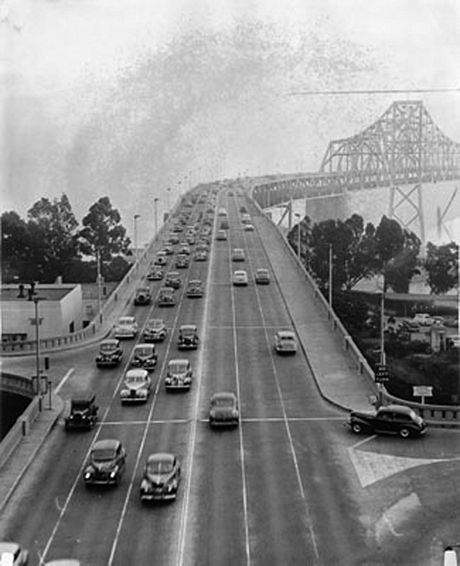

Where are the bikes? The 5-lane configuration was established to feed high speed traffic into a high-speed freeway system that was never built! Go back to 6 lanes, add a bike/ped lane at north (right) side!

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Caltrans (known as the California Department of Highways for most of its existence) has always been biased in favor of automobiles and freeways, and has never shown any interest in providing bicycling infrastructure. It’s obvious that Caltrans bureaucrats were angered by the requirement to include a bike path. How could it be that in 2012 the primary statewide agency in charge of transportation infrastructure neglects its responsibility to provide fair and equal resources to California’s cycling citizens? Are they trying to prove that nobody wants to cycle across the bay by making it unpleasant? So it seems.

Instead of being put on the north side of the new span, with great views of Marin and the North Bay—and the steady rush of clean fresh air that generally comes with the prevailing northwesterly winds, the new bike lane:

- • has been placed on the south side of the new bridge, subjecting everyone to car exhaust

- • faces the old bridge until it is demolished

- • will face the hazy view south toward the Port of Oakland

Worse still, the new lane arrives in mid-Bay at Yerba Buena Island with NO current prospect of continuing to San Francisco.

A 2001 Caltrans study concluded that a continuation of the path was possible, for a cost of $160-387 million. A September 12, 2012 article on SFGate.com suggests it could cost $800 million or even a billion to build new decks hanging off both sides of the west span. This is a calculated effort to stop talk, in this time of fiscal crisis, of full bicycle access to the Bay Bridge.

Daily bicycling has increased by upwards of 70% on both sides of the Bay Bridge but as far as Caltrans is concerned, their only mission is to maintain the bridge as a motor-vehicle-only freeway. It is a sad commentary on the nature of our government that the only way the state transit agency will take bicycling seriously as everyday transportation is when pressured by demonstrations and organized public demands.

Why don’t they take the lead in opening space for cycling instead of doing everything to obstruct, deny, and prevent cycling? Why do we cyclists have to waste our time going to endless bureaucratic meetings and trying to decipher the Byzantine system of transit planning just to get what should be an obvious priority, fair access to the main trans-bay bridge?

Luckily there is a relatively easy solution that doesn’t even require a reduction in motor vehicle lanes, just a simple narrowing of them.

Six lanes on top deck of Bay Bridge in this 1946 photo.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

When the Bay Bridge opened in 1936, the top deck carried 6 lanes of automobile traffic, 3 lanes each way. The lower deck had truck lanes and two railroad tracks that carried Key System streetcars and intercity trains that went all the way to Sacramento. After the 1962 reconfiguration of the Bay Bridge into five lanes inbound on the top deck and five outbound on the bottom, reserved for motorized traffic only, the lanes were widened to match the new freeways that were supposed to crisscross San Francisco—but those freeways were halted by outraged San Franciscans. Caltrans’ insistence that the Bay Bridge is a motorized-traffic-only conduit is a legacy of plans they were never able to complete—and never will be completed! Now it’s time to reverse their wrong-headed approach and open the Bay Bridge to all types of transportation, including bicycles and pedestrians.

What would it take to re-stripe the western span and lower the speed limit to make space for cyclists and pedestrians? Maybe a few days of painting and $50,000? Twice that? The western Bay Bridge approach to SF currently has a speed limit of 50 mph and traffic often moves much more slowly than that.

- • The lanes are super wide and can easily be narrowed by two feet each, freeing up ten feet of space for a dedicated bike-and-pedestrian path along the north edge of the top deck.

- • The speed limit on the famous drive into SF can be reduced to 35 mph so traffic in the narrower lanes will be safer.

- • At the slower speed motorists won’t lose more than a minute or two compared to current speeds (in clear traffic) on their drive from Yerba Buena Island into the City.

Maybe it’s the ease and low cost that makes it a non-starter for the Caltrans behemoth. But Caltrans can’t be left in charge of this decision, having proven again and again that they are beholden to a narrow automobilistic vision of their mission.

Our plan maintains current capacity for auto traffic on the bridge while opening up a path across the entire Bay for cyclists and pedestrians. Isn’t it high time that sustainable transit users get equal access to the most important Bay crossing, especially since it can be done easily and cheaply and at no one else’s expense?