Gay Shame and the Politics of Resistance: Difference between revisions

added more gay shame posters from 2015 |

added new photo |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | ''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | ||

[[Image:Gay-shame-clean-up-the-streets 20150401 105415.jpg]] | |||

[[Image:Gay-shame-tech-is-not-culture 20150401 105121.jpg]] | [[Image:Gay-shame-tech-is-not-culture 20150401 105121.jpg]] | ||

| Line 174: | Line 176: | ||

The Matt Gonzalez campaign demonstrates what anti-establishment activists get when we compromise our values and vote for change: nothing. The real potential of the election was not that a Green Party candidate might get elected, but that conflict might erupt. In a divided city, hope lies in embracing, sculpting, and furthering the divide. We can always build houses in the ruins. | The Matt Gonzalez campaign demonstrates what anti-establishment activists get when we compromise our values and vote for change: nothing. The real potential of the election was not that a Green Party candidate might get elected, but that conflict might erupt. In a divided city, hope lies in embracing, sculpting, and furthering the divide. We can always build houses in the ruins. | ||

Latest revision as of 22:44, 25 June 2022

Historical Essay

by Mattilda, a.k.a. Matt Bernstein Sycamore

Originally published in The Political Edge" in 2004 under the title "Furthering the Divide

Gay Shame poster on Valencia's Democracy Wall, June 2017.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The Golden Age

As a radical queer fleeing to San Francisco in search of hope, the early nineties were a formative time for me. Nevertheless, I would not have guessed that scarcely a decade later, people would look upon that period with nostalgia bordering on delusion. No one is immune to such lapses in judgment. I too remember a time of cheap rent, artistic possibility, and radical direct-action activism, a time when there were almost as many freaks as yuppies, and “community” felt more like a possibility than an advertising gimmick. But I also re-member that, even if no one I knew in 1992 paid more than $300 rent, this felt exorbitant and unaffordable.

Everyone was way too depressed and/or strung out on drugs to do much art. Direct action was certainly far more prevalent than today, but in the early nineties most queer activists looked back wistfully to the late eighties, when a hundred people would show up at an ACT UP meeting (of course, that was because all their friends were dying). In 1992, the city was still filled with freaks of all sorts, but we felt overwhelmed and desperate—we saw the gentrification of the early nineties as a tidal wave we’d unwittingly helped cause, but nonetheless did not know how to stop (little did we know what was to come).

And community? In the early nineties, there was more interconnection between activist groups, as well as more coordination across divides of race, class, and sexuality. With so many queers dying of AIDS, drug ad-diction, and suicide, there was a sense in outsider queer circles that we were bonded together. I felt a palpable sense of potential in embracing a sluttiness infused with the romance of collective desire. But all of these possibilities dissolved quickly when tensions erupted. Small questions of process cracked most activist coalitions. Radical queers betrayed each other as quickly as the families who raised us, and the sluttiness I cultivated left me more heartbroken than healed.

I fled San Francisco just before the hypergentrification that wracked the mid-late nineties (I fled despair and drugs, not gentrification). I came back for eight months in 1996–1997, then left again (the same demons). For three years, I lived in Giuliani’s New York, which offered little more than a rabidly consumerist, commodified, careerist monoculture that drained and disgusted me. In the winter of 2000, I returned to a San Francisco that mimicked all the worst aspects of New York. Entire neighborhoods had been bulldozed to make way for the ugliest luxury housing I’d ever seen. The radical outsider queer culture that I craved, which had nurtured, scarred, and transformed me in the early nineties, had suffered demolition as well, re-placed by high-fashion hipsters looking for the coolest parties.

The winter of 2000 was still the height of the dot.com frenzy, at least as far as the rental market was concerned. I found myself entering Tenderloin buildings with no front doors, walking up bare hallways lit by exposed bulbs, to enter dank thousand-dollar studio apartments filled with numerous preppy blond women all vying for the manager or realtor’s attention: Is the neighborhood safe? (not for you). Is there anything nearby? (a ticket out of town).

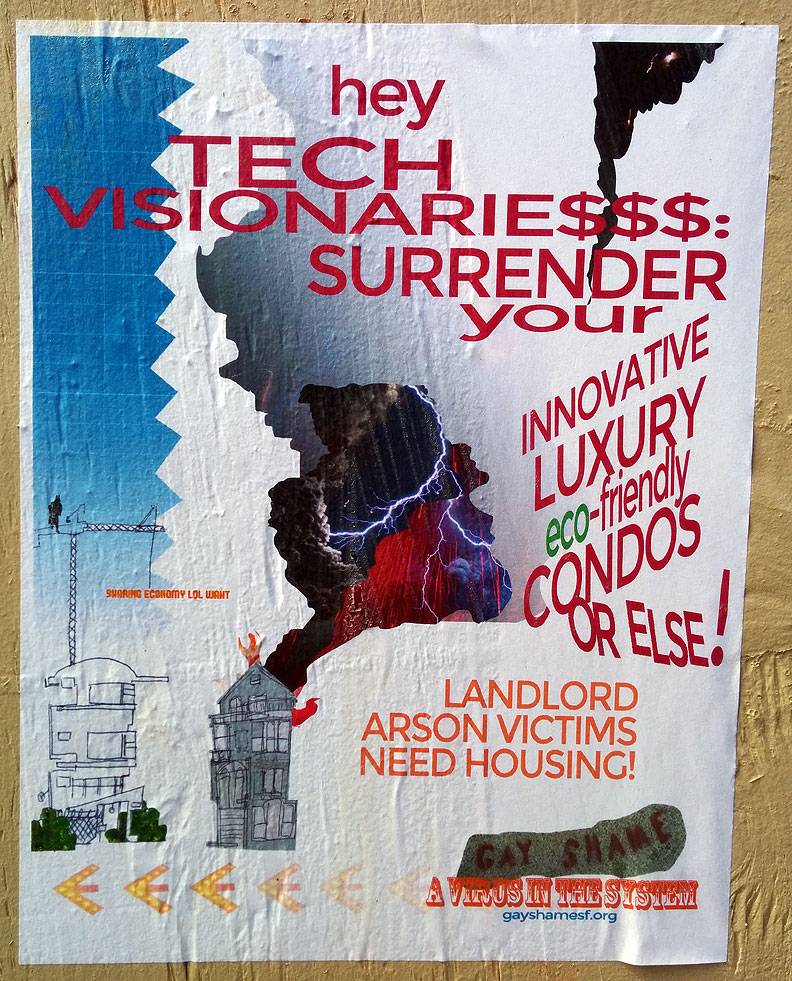

Gay Shame campaigning against tech and condos in 2015.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

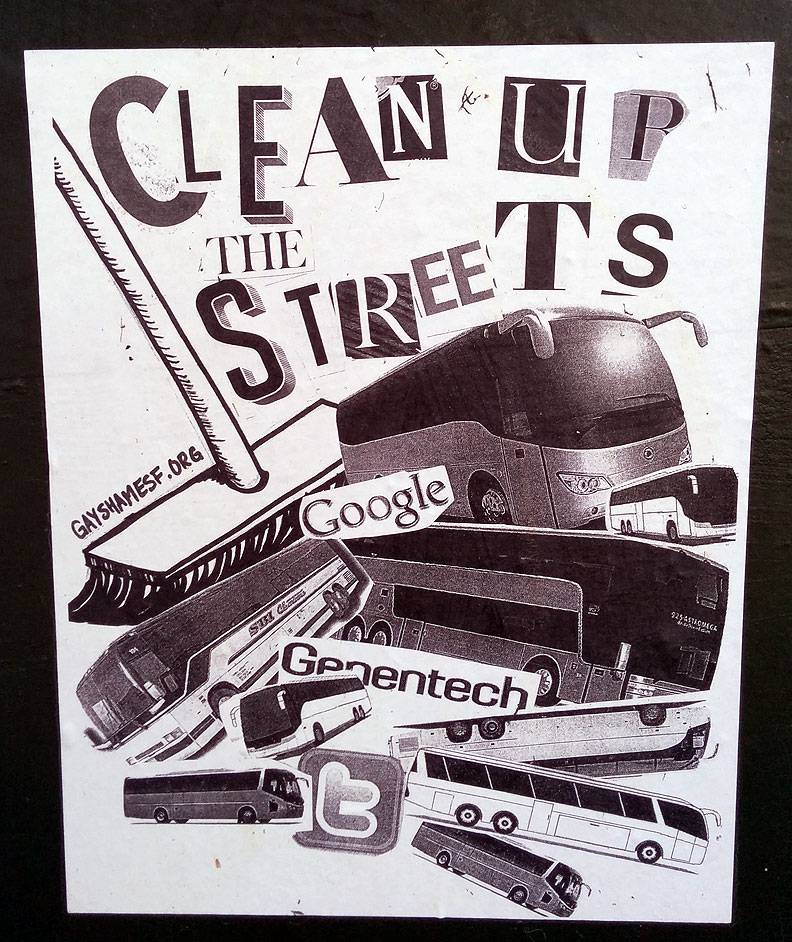

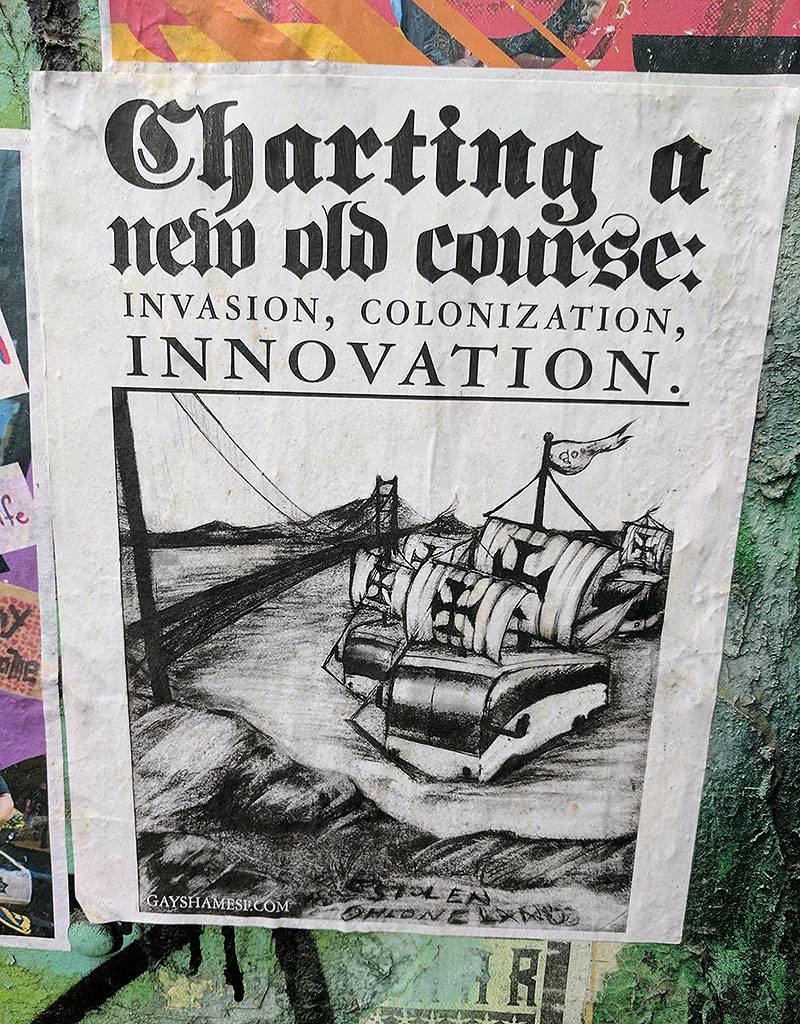

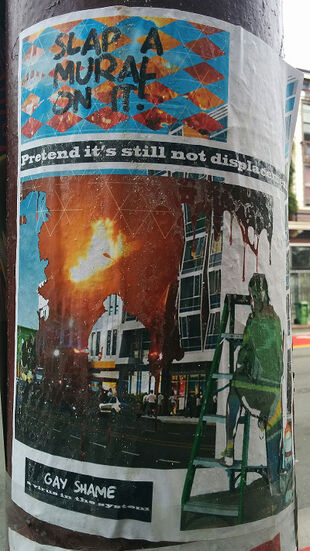

2015 produced an epic outpouring of creative street flyers from Gay Shame.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

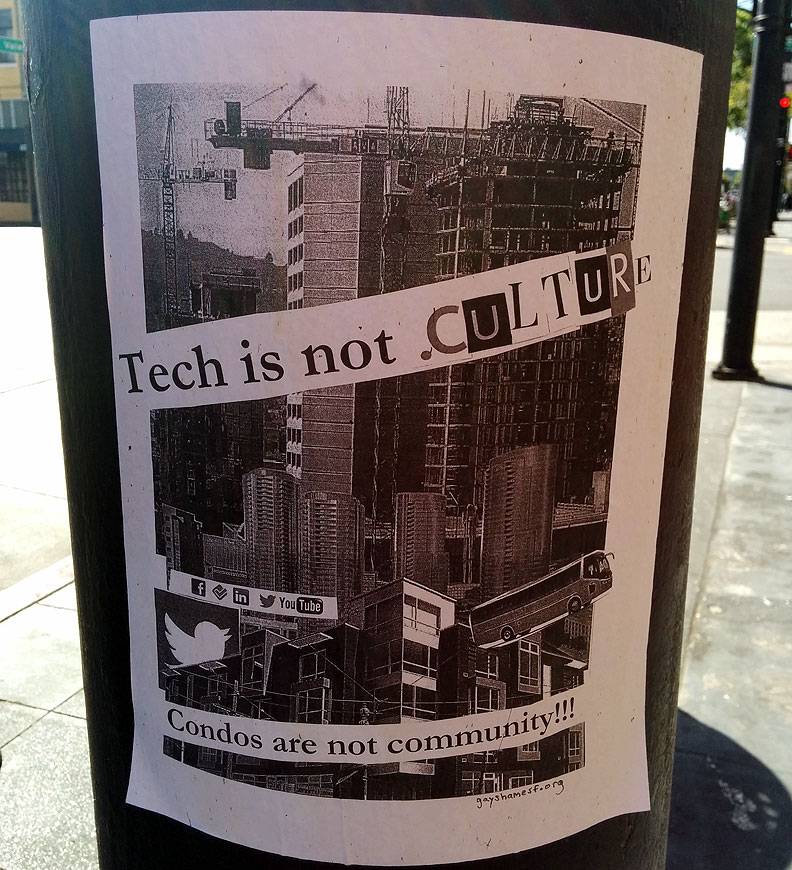

More public shaming directed at the tech influx.

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2015

Gay Shame against the eventually defeated "Monster in the Mission" at 16th and Mission Streets.

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2018

When I finally did get an apartment (yes, a thousand-dollar Tenderloin studio), everything on my rental application was fake—references, former addresses, current job—except my name and social security number. I was magically transformed into a “technical writer” who made $4,800 a month.

At the crest of the dot.com boom (or just before the fall, depending on how you look at it), my technical writing consisted of giving blow jobs in plush off-white hotel beds (you can buy the bed at the W!) while TV sets flashed stock prices (I’m serious). I remember one Tuesday night, after my third trick and on my way to a fourth, stepping into the W Hotel and finding so many people in the lobby that they spilled into the elevators to make deals on their cell phones, cocktails in hand. Outside the Ritz-Carlton one night, there was a couple no older than twenty-five stepping out of a Rolls. The guy wore a waist-coat and held a cigar in one hand and an attaché in the other; the woman wore a full-length fur and gold slip-on heels—they were dressed like someone’s ruling-class grandparents. Stepping into a taxi, all I could think was: at least I’m making cash.

At the height of the dot.com boom, hordes of drunk yuppies crowded the sidewalks in front of posh bars, restaurants, and clubs in “fringe” neighborhoods. It became all too clear who controlled the streets. Hummers sped down side streets like they were at Burning Man (once a neo-hippy festival in the desert, now featured in lavish spreads in Men’s Fitness and Details). The suburbanization of San Francisco was not just a transformation of attitude, it was a decimation of the urban imagination.

Against this disheartening backdrop, in March 2001 I found out about a “squat party” on Market Street be-tween Fifth and Sixth Streets. I was laughing all the way there: a squat party on Market Street, who were they kidding? Would it last longer than ten minutes? Coming from Guiliani’s New York, where activists could hardly march in the street without getting beaten up, I couldn’t imagine a squat on Market Street—in an area filled with boarded-up buildings, yes—but still just blocks from the financial district.

I walked up a flight of stairs into a cavernous room full of brightly painted murals and hundreds of people dancing to live music. Many people I knew from different circles were there, including people I hadn’t seen for ten years. The crowd, mostly young and white, was nonetheless populated by numerous weirdos dressed to the nines in mix-and-match glamour. There was a wide range of class aspirations and social skills. I couldn’t remember a squat party like this in San Francisco. It lasted for hours, without interruption, and without the arrival of the cops. I felt a heady sense of potential that I hadn’t experienced since I’d moved back to San Francisco, and I wondered what else might be possible.

Gay Shame

At some horrible party in the spring of 2001, Oakie, a new friend, asked me, half-joking, what I was doing for Pride.

That was all I needed to hear. Pride? Hiding inside my apartment—what else was there to do? I talked (somewhat wistfully) about Gay Shame, a radical queer alternative to Pride that a bunch of us threw in New York for three years at a collective living/performance space called dumba. I wanted to take it further, hold it in an outdoor public space like Tire Beach, a rotting industrial park on the San Francisco Bay where dis-carded MUNI streetcars are dumped and a concrete factory borders a small grassy area.

Oakie was excited—let’s do it, he urged. He was drunk. We had three weeks until Pride. I’d embarked on way too many projects in which my co-conspirators were flakes, yet I’d come back to San Francisco to find home and all I’d found was a new desperation. I explained what it would take to put on the event—scouting the location, making flyers, wheat-pasting and flyering all over town, getting all the performers and speakers together, finding a sound system and DJs, and so on. That sounds great, Oakie said. I was skeptical, but Oakie’s enthusiasm turned on my manic button and we were a pair.

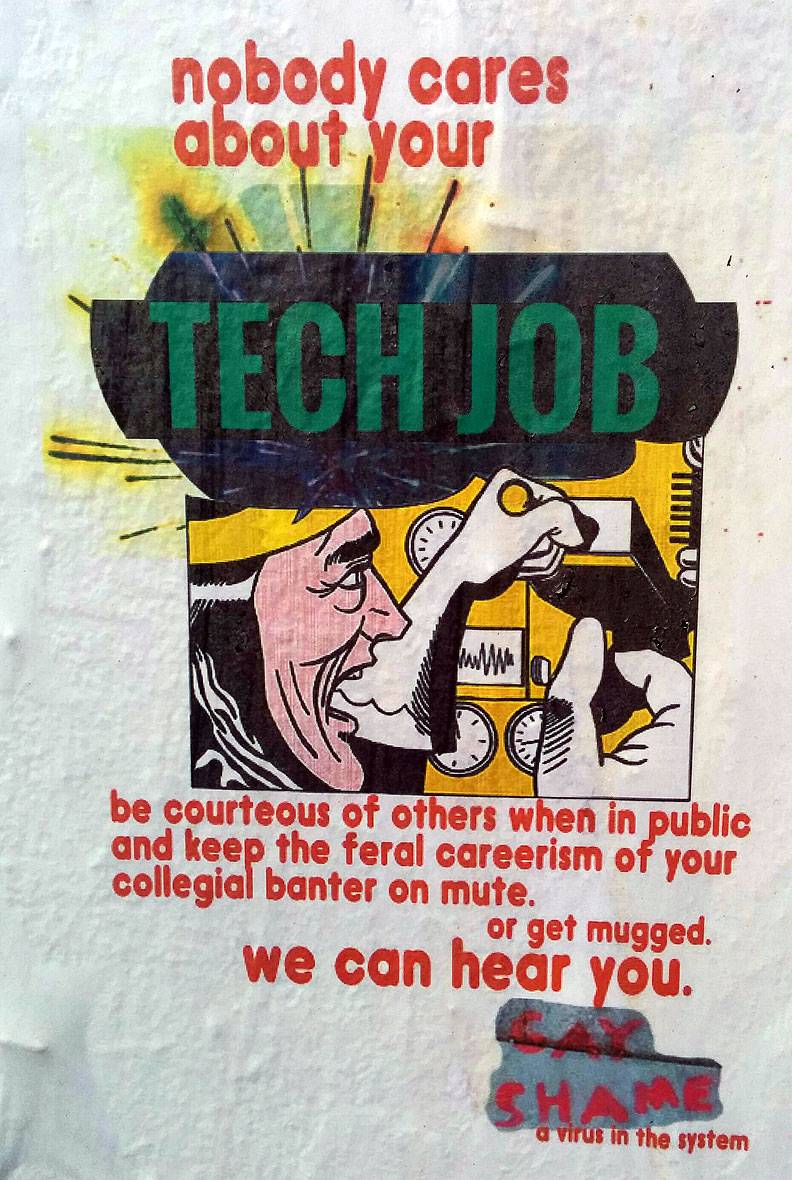

Gay Shame against the "common twitter"!

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2015

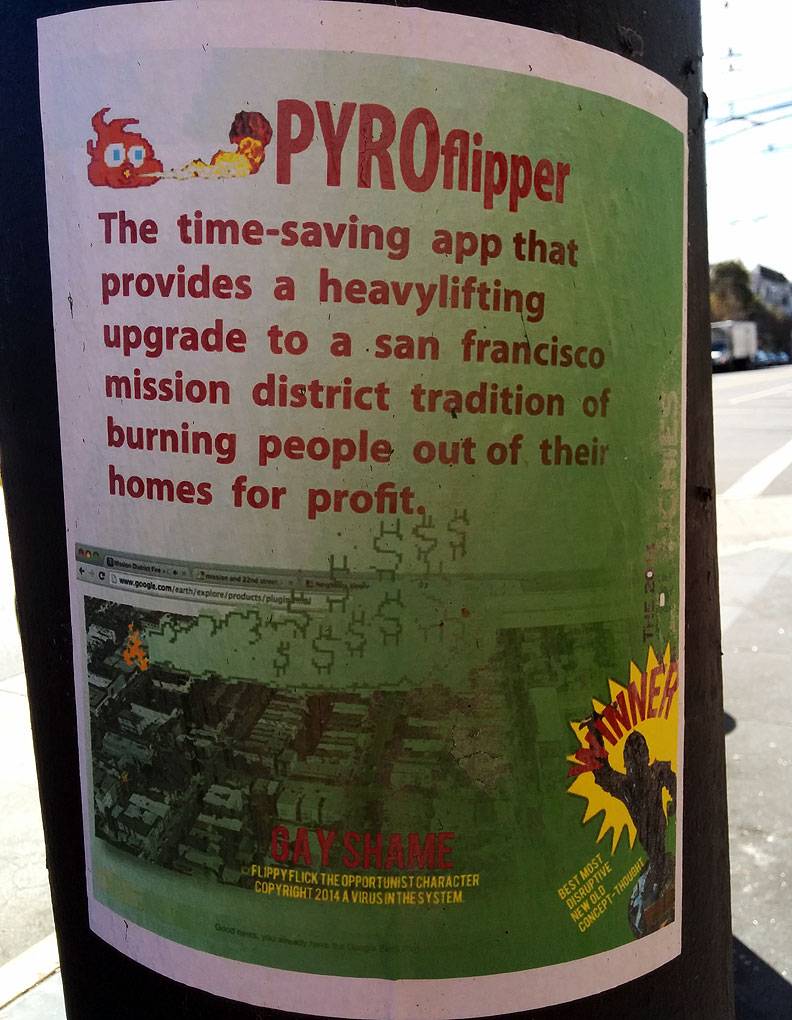

A new app!

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2015

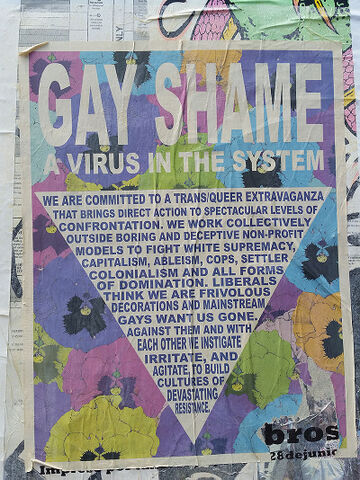

Gay Shame poster, 2017.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Oakie and I called everyone we knew, and about ten of us—queer freaks of all genders (but mostly white and all in our twenties and thirties)—met for three weeks, and then a week before Pride, we held our alter-native. Our hand-written flyers were grandiose—over a photo of the San Francisco general strike of 1934, we proclaimed, “Are you choking on the vomit of consumerist “gay pride?”—Darling spit that shit out—Gay shame is the answer.” We encouraged people to “dress to absolutely mesmerizing ragged terrifying glamorous excess,” and to “create the world you dream of.”

Several hundred people trekked out to Tire Beach and made it our queer autonomous space for the day, which included free food, t-shirts and various other gifts, bands, spoken word, DJs (and dancing), a kid space for children, and speakers on issues including San Francisco gentrification and the U.S. colonization of the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, as well as prison, youth, and trans activism. We encouraged people to participate in creating their own radical queer space and culture instead of just buying a bunch of crap (like at Pride), and people argued about political issues, painted, poured concrete and made a mosaic, dyed hair, and mud-wrestled naked.

In spite of our efforts to create a politicized space, many participants were rude to the speakers and seemed uninterested in anything beyond partying and socializing with their friends. We realized that, as organizers, by separating the “politics” from the “partying,” the speakers from the bands, we unwittingly helped participants ignore our radical intentions. We resolved to be more confrontational in the future, to make our political agenda clear.

Ten months later, we came up with the Gay Shame Awards, where we would reward the most hypocritical gays for their service to the “community.” We sought to expose both the lie of a homogenous gay/queer “community,” and the ways in which the myth of community is used as a screen behind which gay people with power oppress others and get away with it.

Some of the Gay Shame posters on Democracy Wall on Valencia in 2017.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

We held the Gay Shame Awards in Harvey Milk Plaza, at the center of the white-washed gayborhood of the Castro, and bestowed awards in eight categories, including “Best Target Marketing” and “Making More Queers Homeless. ” We served free food and gave out homemade patches and artwork, Gay Shame buttons with the image of Rosie O’Donnell or George Michael, and various other delicacies. As requested, people dressed to excess, in exaggerated, smeared makeup and glitter, torn ball gowns, and crumpled dress shirts—one participant wore a dress made entirely out of shopping bags—the Gap, Starbucks, Abercrombie and Fitch, and other gay mainstays—and stiltwalkers dressed in garbage bags added to the festivities.

We burned a rainbow flag after each award was announced, and the climax of the event occurred when we moved sofas and the sound system into the streets for a dance party. This was a fiery moment—I think we were a little in disbelief that it all went so smoothly. As police negotiators handled the cops, we held Castro and Market Streets for several hours before packing up, with no arrests. The crowd included many queers both a generation older and a generation younger than us, and even straight tourists gaped in disbelief, and wondered: is it always like this?

The Gay Shame Awards inseparably connected spectacle and politics. We started to think seriously of Gay Shame as a direct-action group that fused the theatricality and pageantry of the seventies drag troupe the Cockettes (The Cockettes movie was premiering at the Castro Theater), the militance of late-eighties/early-nineties ACT UP, and the anticapitalist direct action of Reclaim the Streets.

The Pride Parade adapted the Budweiser advertising slogan for its official theme: “Be Yourself—Make It a Bud” became “Be Yourself—Change The World.” We prepared to confront this assimilationist monster by installing our festival of resistance inside the barricades. Two months of planning culminated in volunteer parade marshals instigating violence against us, and the bashing and arrest of two Gay Shame participants. We placed our official Budweiser Vomitorium outside the parade gates and resolved to be more prepared in the future.

If Gay Shame’s first major transition moved us from festival of resistance to direct action extravaganza, our second transformation involved broadening our scope, from focusing primarily on Gay Pride to challenging all hypocrites, and specifically to confronting the racist policies of a “gay-friendly” politician. This politician was none other than the illustrious Gavin Newsom, soon to catapult to national fame, but at this point merely your average straight, white ruling-class city council (Board of Supervisors) member busy criminalizing homeless people for getting in the way of tourist dollars.

Just before Halloween 2002, Gay Shame went to Newsom’s Marina district with a Haunted Shanty-town, which we installed on the block alongside his campaign headquarters and four businesses he owned (a bar, a café, a restaurant, and a wine store). We then rolled down a “bloody” carpet and held the Exploitation Runway in the middle of bustling Fillmore Street. This was a scripted event in which impersonators of key exploiters walked the runway in several categories, including Gentrification Realness (Old School and New School), More Blood for Oil, Displacement Divas, Gavin Authenticity, Luxurious Liberals, and Eviction Couture.

The Marina action was another example of how our spectacle served to draw spectators in rather than al-ienate them. Marina yuppies gathered around to observe our glamour and we distributed a pamphlet ex-posing Newsom’s antihomeless policies. The cops harassed us so we made an emergency decision to take the runway up to Pacific Heights and confront Newsom at a nearby campaign function. Our frantic decision turned out to be the most beautiful and symbolic moment of the evening, as 150 of us pushed the sound system and our shantytown up a steep incline to Pacific Heights, the richest part of San Francisco.

Months later, in February 2003, Gavin Newsom held a lavish fund-raiser for the LGBT Center, a blatant (and successful) attempt to pander to San Francisco’s gay elite in order to bolster his looming mayoral campaign against several gay candidates. Our banner read, “Gavin Newsom Comes Out of the Closet—As a Fascist!” We gathered not only to protest Newsom’s closeted right-wing agenda, but to call attention to the hypocrisy of the center for welcoming Newsom’s dirty money instead of taking a stand against his blatantly racist and classist politics.

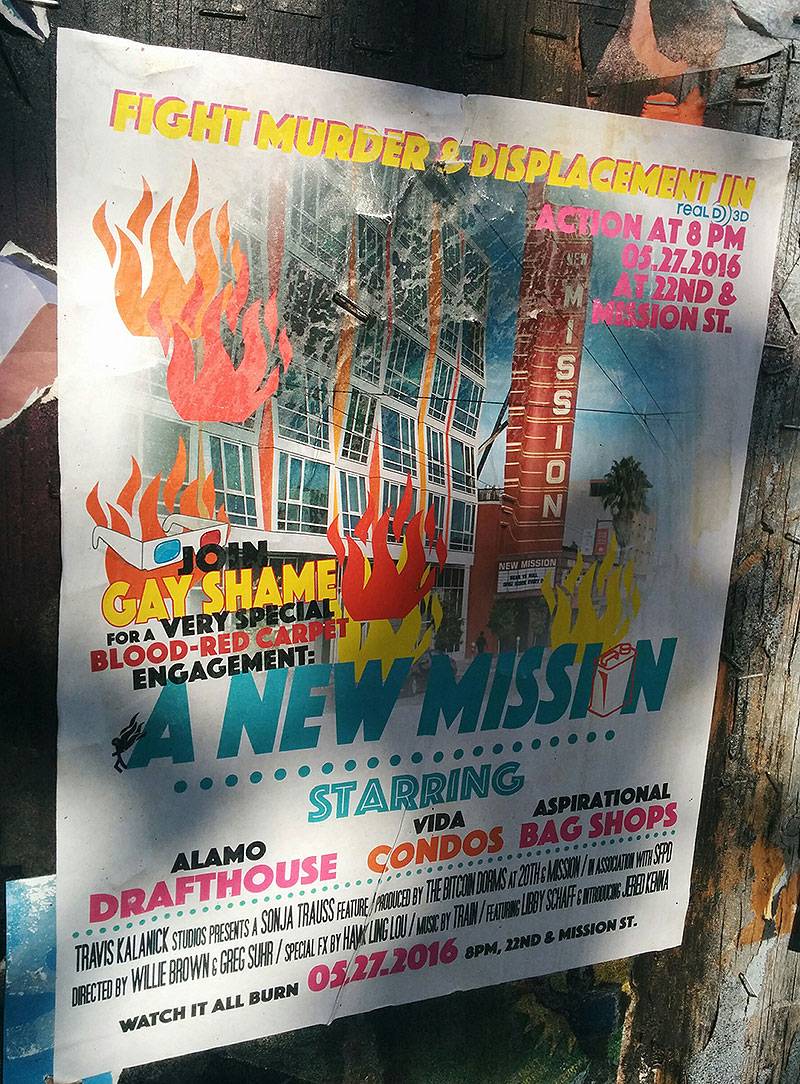

In 2016, Gay Shame was fully engaged in campaigning against gentrification in the Mission.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

We found out about the event at the last minute, and therefore had little time to plan much more than a banner drop and a flyer. In a flourish we handed out hot-pink bags of garbage to smiling patrons. Attendees, thinking perhaps we were part of the festivities, even agreed to pose for pictures while holding the delicate-ly arranged trash. In spite of the tame nature of our protest, police officers called by “our” center began to bash us as soon as they escorted Newsom inside. One officer hit a Gay Shame demonstrator in the face with his baton, shattering one of her teeth and bloodying her entire face. Four of us were arrested; one arrestee was put into a chokehold until he passed out.

The press loves blood, and the spectacle of the SFPD bashing queers outside of San Francisco’s LGBT Cen-ter was not lost on local media. Police violence became a cover story in local gay papers and even corporate newspapers, as well as on network news channels. With the arrest of antiwar protesters ten days later, we were unable to use this public outcry much to our advantage in indicting either the police or the center. Those arrested at the center were held in jail for up to three days and faced charges as ridiculous as assault on a police officer (four counts for me) and felony “lynching,” an antiquated term for removing someone from arrest. Our court cases lasted eight months and charges were only reduced to infractions after our publicized subpoena of Gavin Newsom.

Just preceding the official start of the U.S. war against Iraq, Gay Shame meetings swelled from around a dozen participants to thirty or forty. We participated as an affinity group in the mass direct action organized for the day the war against Iraq began. Our goal was to block a specific exit ramp from the highway, and on March 20, 2003, we gathered furniture, a refrigerator, huge pieces of metal, and construction barricades for this purpose. Nonetheless, we were unable to secure the ramp for long, and instead turned into a roving band of marauders, supporting various affinity groups throughout the city. The next several days were a volatile time of public protest and arrests of 2,100 protesters—though perhaps these arrests would have been more effective if they’d occurred before the official start of U.S. aggression. The crackdown was shocking. Police helicopters flew overhead all night and protesters were thrown into police vans for marching on the sidewalk. It seemed war had broken out in San Francisco as well.

By the time of the Second Annual Gay Shame Awards, we were back to less than a dozen at meetings. Perservering, we added several new awards, including the Wargazm Award and Best Front-Row Seat to Watch Police Brutality (the center). We held a Walk of Shame, where we marched to the Castro and bestowed our prizes, including a rainbow phallus as the Gender Fundamentalism Award, and a framed picture of Dan White, the murderer of Harvey Milk, as the Auntie Tom Award. The highlight of the ceremony occurred when we burned an effigy of Newsom in the middle of 18th and Castro Streets (the location of numerous Newsom for Mayor signs). People danced in jubilation as the effigy burned to the ground and a fire truck arrived to disperse us.

Pride once again involved arrests, as Gay Shame participants who attempted to enter the parade ahead of Newsom were attacked by Newsom staff, and then sent to jail with felony charges—only dropped after in-tense pressure. As the mayoral election loomed, and Newsom held an enormous lead in public opinion polls, Gay Shame came up with the Mary for Mayor Campaign, in which a new candidate—Mary—entered the mayoral race and delivered a truly radical platform that included converting members of the SFPD to nutritious compost, supporting terrorism in all forms, and advocating forced relocation of loft condominium owners into the San Francisco Bay. In addition to a fictitious candidate with grandiose plans, we created numerous organizations who wholeheartedly supported Mary in her campaign: Terrorists Against Gavin (TAG), Fashionistas Against Gavin (FAG), and Riff-Raff Against Gavin (RAG). TAG resurrected the image of Patty Hearst, a.k.a Tania, in the 1970s Symbionese Liberation Army, gun in hand, and FAG pronounced: “Gavin Newsom is so last season.”

The Mary for Mayor action included all of the Gay Shame hallmarks. First, a festival of resistance, this time outside a Newsom fund-raiser in the heart of the theater district. Second, a ceremony, in this case the delivery of Mary’s platform, including a campy theme song resurrected from mid-nineties club culture (“Tyler Moore/Mary”). Third, elaborate and disastrous costumes that included construction site material, bloody underwear, and a stuffed snake. Fourth, a ’zine that detailed both the vicious platform of Gruesome Newsom and the liberatory absurdity of Mary’s largesse. Fifth, the usual assortment of hand-painted signs, free food, banners, and buttons. And sixth, an event that markedly differed both in scale and scope from our original intentions.

The Mary for Mayor Campaign Kick-Off commenced down the block from the Newsom fund-raiser. The police had already arrived in order to prevent us from moving closer, and immediately threatened to confiscate the sound system and arrest anyone who disobeyed their orders. Of course, we quickly took to the street, blocking traffic in front of the gala. When cops began to surround us we moved a block away, in front of the luxurious and fashionable Clift Hotel, and finished our ceremony in the middle of the street. We occupied the whole block for over an hour while burning effigies, delivering Mary’s platform, attempting to enter the Clift, and—of course—dancing, prancing, and romancing.

The Mary for Mayor Campaign Kick-Off was both more and less participatory than any of our previous events. We recruited people on the spot to improvise Mary’s campaign pronouncements, and encouraged the crowd to join us in everything from blocking the street to doing runway outside the Clift Hotel. We organizers wanted the crowd to engage in the same level of risk-taking as we did. But by the time we marched through the Tenderloin to City Hall, our numbers had dwindled from about 150 to 40. The Mary for Mayor Campaign arrived at City Hall to a rude rebuff by members of the sheriff’s department. Of course, Mary had plenty to do outside.

The Divide

Gavin Newsom was annointed mayor way before the official campaign had begun. Both the San Francisco Chronicle and the San Francisco Examiner ran story after story about how Gavin Newsom was “solving” the homeless issue (that is, getting rid of homeless people). Newsom’s high-fashion wife, Kimberly Guilfoyle-Newsom, former Victoria’s Secret model and assistant district attorney, appeared as a “legal expert” on Fox News, Entertainment Tonight and CNN. As the election approached, Details ran a glowing appraisal of San Francisco’s ascendant first couple. National news focused on how wacky it was that a candidate such as Newsom, who was in favor of gay marriage and medical marijuana, could be cast as “conservative”—only in San Francisco, they cooed. It’s conventional wisdom in the mainstream press that politicians considered “moderate” or “conservative” in San Francisco would be flaming liberals anywhere else. This ignores the reality that big-money, prodevelopment candidates have dominated the mayor’s office for the entire history of San Francisco.

As gay “progressive” Tom Ammiano moved swiftly to the center, prodevelopment “moderate” Susan Leal (Willie Brown lackey—and lesbian!) entered the race in order to split the “gay vote.” When former supervisor (and daughter of a former mayor) Angela Alioto entered the race, she portrayed herself as a more “serious” (read: rich) challenge to Gavin Newsom. But the candidate portrayed as the savior of progressive causes was the last to enter the race, Board of Supervisors president (and Green) Matt Gonzalez.

After the mayoral election was whittled down to two candidates—Gavin Newsom and Matt Gonzalez—progressives, hipsters, and formerly apolitical fringe types all united behind the banner of Matt for Mayor. Bars throughout the city became sites of voter registration drives, and scenesters usually intent on getting their cheap liquor into a bar unseen were suddenly frantically adoring Matt. In the month leading up to the election, every night there was a different fund-raiser for Matt Gonzalez at some hip (but not too hip) venue. Matt for Mayor buttons became the new fashion statement for the downwardly mobile. Punx Against War, the same people who had thrown the squat party on Market Street two years earlier, organized their own Matt for Mayor get-out-the-vote drive at UN Plaza.

While some championed this new interest in electoral politics by usually “apathetic” nonvoters, it de-pressed me to see activists I admired and respected (for trying to create outsider culture) encouraging people to vote. I planned to vote for Matt Gonzalez, but had no illusion that this would lead to any lasting change. Seeing the fringe hipoisie uniting with such fervor around the alleged possibilities of voting exposed the lack of commitment in “anti-establishment” subcultures to actually challenging mainstream morals and the sham of electoral politics.

Gavin Newsom barely defeated Matt Gonzalez at the polls—in spite of outspending him 10 to 1 and uniting every big-money Democrat across the country in a desperate quest not to “lose” San Francisco to a Green (Bill Clinton, Al Gore, and Jesse Jackson all campaigned for Newsom). On the eve of the election, Gay Shame put out a call for a mobilization at Gavin Newsom’s victory party. This was an informal call, and not an official Gay Shame action. Still, we fliered several hundred people at the Matt Gonzalez for Mayor party and also posted on Indymedia. In total, only twenty people showed up—two from the Matt Gonzalez “victory party.” It was depressing to realize that doing something as basic as protesting the election of a ruling- class hypocrite had now become so marginal. As Gonzalez supporters “celebrated” Matt’s loss by boozing it up (free beer!), we stood out in the rain and attempted to harass the luminaries as they basked in the reflected glow of money and power.

Gay Shame has always had an uneasy relationship to hipster culture. To be sure, we have benefited from a certain cachet among the taste makers and deal breakers of the indie white Mission scene. Nonetheless, by Gavin Newsom’s election, our initial popularity among the jaded had essentially collapsed—we were seen as too bitter, too judgmental, too white, too confrontational, too serious, too young, too cliquish, too angry, too whiny, too disorganized, too elitist, and too extreme. Our brazen challenge to “community” lies was seen as brash and unnecessary when the “community” was closer to home than the wealthier and more blatantly hypocritical targets in Gaylandia. As we consistently faced police harassment and brutality, participants at our demonstrations became increasingly jittery. When Gay Shame wasn’t quite so new, and once we started taking bigger risks, we were no longer a hot commodity in a subculture attuned to the latest trend. Perhaps, as well, it became clearer just what Gay Shame actually was: not so much a movement as a small group of alienated queers trying desperately to do something.

If the fringe was divided, then so was the city. While Gavin Newsom’s election was no surprise to me, his slim margin of victory blatantly revealed the existence of two San Francisco's that rarely meet. I confess that I’ve spoken to only one person who expressed any intent to vote for Gavin Newsom, and that was someone I met on a phone sex line. The beauty (and danger) of San Francisco is that you can choose to interact only occasionally with people you hate. I’m sure I’ve sucked off plenty of Gavin Newsom supporters, but I’ve rarely interacted with them otherwise (except, of course, at protests).

When Newsom immediately began talking about bridging the gap between two cities, everything could have exploded. Instead, Gonzalez demonstrated his “skills” as a politician, and echoed Newsom’s rhetoric. Other than a small “funeral” Gay Shame held at the Newsom inauguration, no one seemed to care—Gavin Newsom had won fair and square, right? Even when it was exposed that city workers were paid to walk precincts for Newsom, Gay Shame was called “immature” for daring to challenge Newsom’s rule.

Three months after the election Newsom pulled the ultimate risk-free political stunt and “legalized” gay marriage. Throngs of gay people from across the country descended upon City Hall day and night, camping out, sharing snacks and wine, and toasting Gavin Newsom as the vanguard leader of gay civil rights. This was a brilliant maneuver by a ruling-class politician with national ambitions and enough capital to hire only the best political consultants (many of them gay). What had formerly been a divided city was now a city united around marriage “rights.”

The gay marriage hoopla paralyzed Gay Shame. If we already felt marginalized for continuing to protest Newsom after his election, now we felt like pariahs. It was obvious to us that if gay marriage proponents wanted real progress, they’d be fighting for the abolition of marriage (duh), and universal access to the services that marriage can sometimes help procure: housing, healthcare, citizenship, and so on. Instead, gay marriage proponents want to fundamentally redefine what it means to be queer, and erase decades of radical queer struggle in favor of a sanitized, “we’re-just-like-you” normalcy (with marriage as the central institution, hmm . . . sounds familiar). Just the fact that challenging the gay marriage bandwagon became immediate heresy exposes the silencing agenda of gay marriage proponents as they move steadily toward assimilation into the imperialist, bloodthirsty status quo.

As Newsom’s popularity surged, Gonzalez announced that he would retire from public office after his term as president of the Board of Supervisors. One can only assume that Gonzalez felt he’d gotten as far as he could, and it was time to call it quits—fuck “the movement”! Some argued that he was never a “real” politician, that he’d been recruited just a few years earlier (by Tom Ammiano) to run for the Board of Supervisors, and that he’d become caught up in a system he viewed with increasing distaste. Yet Gonzalez’s acceptance of contributions from some of the city’s most notorious slumlords, and his immediate capitulation to Newsom’s call for “unity,” suggest that Gonzalez was far more seasoned in the less savory aspects of politics than his most ardent supporters would like to imagine.

Two more Gay Shame posters on poles near 22nd and Mission, 2016.

Photos; Chris Carlsson

If the dot.com era left outsider queers, artists, and activists feeling helpless and hopeless, then the crash opened up a window of opportunity as rents lowered (slightly) and resistance felt (slightly) less futile. The Matt Gonzalez campaign/Gavin Newsom victory may be closing that window. With Newsom continuing the Willie Brown legacy of hyperdevelopment and the dismantling of systems of care, gentrification continues unabated, especially in the Bayview, Mission, and Tenderloin, and things look a lot less rosy.

For non-mainstream queers, these are especially dangerous times. Just two blocks from my apartment, a block of Polk Street known for street hustling and speed dealing has been transformed into the site of not one, not two, but four yuppie straight (or “mixed”) bars—all replacing lower-end gay bars. My Place, a South of Market gay bar known for decades as a cruising hole, was shuttered by the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control, sending shock waves through South of Market leather bars that now police their premises to root out sex deviants. As gay people of all political affiliations, ethnicities, and social backgrounds (including the publisher of my novel and my ex-boyfriend) rush to tie the knot, what is being discarded is a queer identity that demands fundamental changes in the dominant culture, not inclusion.

The debate over gay marriage presents only two sides to the story: foaming-at-the-mouth conservatives who think gay marriage marks the death of Western civilization (I wish), and rabid gay assimilationists who act as if gay marriage is the best thing since Will and Grace. When anti-assimilationist queers are mentioned (which is rare), we’re presented as rebels within the “community.” But when gay landlords evict people with AIDS to get higher rents, when Castro residents fight a queer youth shelter because it might get in the way of “community” property values, when gay bar owners call the cops to arrest homeless queers—this exposes the lie of a queer “community” that serves only those in power.

The fight between pro-marriage and anti-marriage queers is not a disagreement between two segments of a community, but a fight over the fundamental nature of queer struggle. When Newsom weighed in on one side, he gained not only the loyalty of the rich gays who got him elected, but the support of liberals across the sex-and-gender spectrum (especially straight lefties who were suddenly happy to support gays, even though they’ve never had much interest in queer lives). As former foes of Newsom capitulate to this new-found “unity,” resistance can seem all the more useless.

The Matt Gonzalez campaign demonstrates what anti-establishment activists get when we compromise our values and vote for change: nothing. The real potential of the election was not that a Green Party candidate might get elected, but that conflict might erupt. In a divided city, hope lies in embracing, sculpting, and furthering the divide. We can always build houses in the ruins.

published originally in The Political Edge ed. Chris Carlsson (City Lights Foundation: 2004)