Crocker's Spite Fence: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(added photo) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | |||

''by James Sederberg'' | |||

[[Image:Rulclas1%24spite-fence-photo.jpg]] | [[Image:Rulclas1%24spite-fence-photo.jpg]] | ||

| Line 4: | Line 8: | ||

''Photo: Edweard Muybridge, 1877'' | ''Photo: Edweard Muybridge, 1877'' | ||

[[Image:Charles Crocker Mansion from California Street near Taylor 1870s wnp37.00877.jpg|800px]] | |||

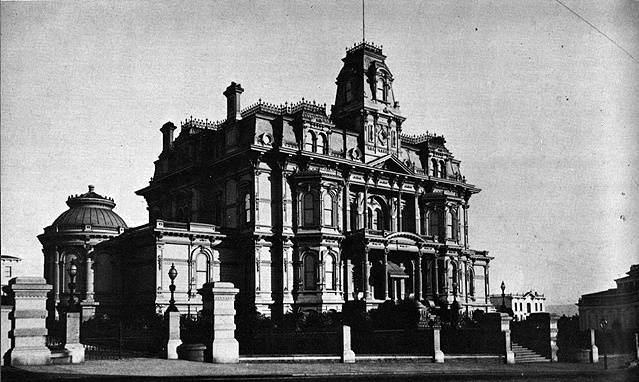

'''Charles Crocker mansion from California Street near Taylor, 1870s.''' | |||

''Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.00877'' | |||

Charles Crocker was a man who was used to getting what he wanted. A former dry-goods merchant, the six-foot tall, three-hundred pound Crocker had made his fortune by overseeing and financing the Central Pacific Railroad. In order to find enough labor for this grueling and monumental task, Crocker (along with the other members of the [[The Octopus and the Big Four|Big Four]]) shipped over thousands of low-wage Chinese workers (derogatorily called "coolies"). He acquired the land on which to lay the tracks by simply buying the right-of-way at the appraised value with or without the consent of the owner. No obstacle was going to get in the way of Crocker or the progress of Capitalism. | Charles Crocker was a man who was used to getting what he wanted. A former dry-goods merchant, the six-foot tall, three-hundred pound Crocker had made his fortune by overseeing and financing the Central Pacific Railroad. In order to find enough labor for this grueling and monumental task, Crocker (along with the other members of the [[The Octopus and the Big Four|Big Four]]) shipped over thousands of low-wage Chinese workers (derogatorily called "coolies"). He acquired the land on which to lay the tracks by simply buying the right-of-way at the appraised value with or without the consent of the owner. No obstacle was going to get in the way of Crocker or the progress of Capitalism. | ||

| Line 32: | Line 42: | ||

'''Grace Cathedral at California and Taylor on the former site of the Crocker Mansion and Spite Fence.''' | '''Grace Cathedral at California and Taylor on the former site of the Crocker Mansion and Spite Fence.''' | ||

[[BAY AREA COUNCIL | Prev. document]] [[Mayors 1850-1897 | Next document]] | [[BAY AREA COUNCIL | Prev. document]] [[Mayors 1850-1897 | Next document]] | ||

[[category:Power and Money]][[category:Nob Hill]] [[category:1870s]] [[category:1880s]] [[category:1900s]] [[category:Famous characters]] [[category:buildings]] | [[category:Power and Money]][[category:Nob Hill]] [[category:1870s]] [[category:1880s]] [[category:1900s]] [[category:Famous characters]] [[category:buildings]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:17, 25 December 2021

Historical Essay

by James Sederberg

The Spite Fence built by Crocker to block light to a neighbor is seen in this picture. The fence is just behind the large white building in the center, partly blocking the street; it's held up with wooden beams.

Photo: Edweard Muybridge, 1877

Charles Crocker mansion from California Street near Taylor, 1870s.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.00877

Charles Crocker was a man who was used to getting what he wanted. A former dry-goods merchant, the six-foot tall, three-hundred pound Crocker had made his fortune by overseeing and financing the Central Pacific Railroad. In order to find enough labor for this grueling and monumental task, Crocker (along with the other members of the Big Four) shipped over thousands of low-wage Chinese workers (derogatorily called "coolies"). He acquired the land on which to lay the tracks by simply buying the right-of-way at the appraised value with or without the consent of the owner. No obstacle was going to get in the way of Crocker or the progress of Capitalism.

Nicholas Yung was a native of Germany who had arrived in the U.S. in 1848. He established himself in the mortuary business and in 1855 he and his wife bought a corner lot at the top of the California Street Hill and built a modest home. In those days the treacherous climb made Yung's hilltop home seem almost isolated and removed from the hustle and bustle of Gold Rush San Francisco. The location offered Yung and his family a stunning view: to the north, they could look out to the Golden Gate; to the east there was the Bay and the Berkeley Hills; and to the south they could watch the sprawling, teeming city below. All around the house was a great flood of fresh air and sunlight.

In April, 1878 the California Street Line Cable Cars commenced operations. The newfound accessibility turned the once remote California Street Hill into San Francisco's most exclusive real estate area. Leland Stanford and Mark Hopkins both built palatial mansions on what had become -- almost overnight -- Nob Hill. Charles Crocker, never one to be outdone, planned to build his house even higher up the hill than his rivals. He planned a grand spectacle of his wealth and power including a 75-foot tower from which he could view the goings-on of San Francisco.

Money, of course, was no object to Crocker -- but Nicholas Yung (who owned the northeast corner of Crocker's block) was. Crocker made several offers to buy out Yung at the market price but Yung refused. As progress on the mansion continued, Crocker became more and more desperate to have Yung and his house removed. When dynamite was used to level the craggy hilltop for his home, Crocker apparently ordered his workmen to aim the flying debris towards Yung's house. But the undertaker held his ground.

With the mansion just about completed, Crocker made one final attempt to buy Yung's property, doubling his original offer. Yung however, because of the beautiful view, the wishes of his family or his own sense of defiance and pride, refused Crocker yet again. This time the Railroad Baron had a plan: he ordered his workmen to construct a three-sided wood fence around Yung's house. The fence rose forty feet into the sky and the view, the sunshine, and the fresh air that the Yung's had enjoyed were all but completely taken away. With only northern exposure left to them, the Yungs felt as if they were living at the bottom of a well. The fence was in place and the battles over it and what it represented were just beginning.

"There are uglier buildings in America than the Crocker House on Nob Hill, but they were built with public money for a public purpose; among architectural triumphs of private fortune and personal taste it is peerless." --Ambrose Bierce

Crocker's Spite Fence, as it was known, became one of The City's most popular sight-seeing attractions. People would ride the cable car to the top of Nob Hill to stare at and to talk about this symbol of Capitalist power over the "little man." Californians loved to be shocked into loathing Crocker and all that he represented. The newspapers, echoing the ire of most San Franciscans, began calling the fence "Crocker's Crime."

Enter Denis Kearney. The late 1870s were a time of nationwide economic depression and high unemployment. In San Francisco rage was directed toward not only the Railroad Barons but against the low-wage Chinese laborers who, many felt, were threatening the jobs of "white Americans." Kearney, capitalizing on this rage, formed the Workingman's Party of California (WPC). The party's slogan was "The Chinese Must Go." Because of the economic conditions and the resentment that they created, the WPC managed to sweep the city elections of 1878 and 1879. The Spite Fence was a symbol that fired up the WPC members and motivated others to join. Although racism was one of the platforms of the WPC, many members joined more for the labor issues than for the politics of hate.

On October 29th, 1878 the WPC held a mass rally on top of Nob Hill. The setting was perfect for inciting the rage of the laborers. Lime barrels were set on fire and cast their light upon the ostentatious display of the Capitalist's wealth. Hundreds of armed men lined the halls of Crocker Mansion ready to defend him and his million dollar art collection if violence were to break out. Over two-thousand WPC members stood out in the cold night air to hear Kearney, in his incendiary oratorical style, rally them against the supposed enemies:

"When the Chinese question is settled," he roared, "we can discuss whether it would be better to hang, shoot, or cut the capitalists to pieces." He told the crowd that if Crocker didn't remove the Spite Fence by Thanksgiving Day, Kearney and the WPC would tear it down themselves. The battle lines had been drawn. Unfortunately, that particular battle never took place. Two days after the Nob Hill rally, Kearney was arrested for attempting to incite a riot. Although he was released before Thanksgiving, the WPC didn't climb up the hill that day and Kearney, seemingly more anti-Chinese than anti-Capitalist, never made good on his promise to tear down the fence.

The Spite Fence stayed in place until, a few years later, Yung eventually sold out to Crocker and the fence was torn down. Just a few years after that, in 1906, the Great Fire made cinders of all but one of the millionaire's digs. Today the impressive Grace Cathedral stands where Crocker and Yung once lived.

Grace Cathedral at California and Taylor on the former site of the Crocker Mansion and Spite Fence.