Third Worldism in 1970s San Francisco: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

[[Image:15.gif|64px|left]] '''Listen to an excerpt from "With the Soul of a Human Rainbow" read by author Dr. Jason Ferreira:''' | [[Image:15.gif|64px|left]] '''Listen to an excerpt from "With the Soul of a Human Rainbow" read by author Dr. Jason Ferreira:''' | ||

< | <iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/15TenYears--losSieteBlackPanthersThirdWorldismInSf" width="500" height="30" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe> | ||

by [http://www.archive.org/download/15TenYears--losSieteBlackPanthersThirdWorldismInSf/15JasonFerreira23rdAndValenciaMastered2.mp3 mp3]. | |||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

[[Image:Tenyears-tour-02.gif|link=Managua North: San Francisco's Solidarity Movement]]<br> | |||

Previous stop: [[Womens Liberation Changed Medicine|Women's self-health]] <br> | |||

Next Stop #16: [[Managua North: San Francisco's Solidarity Movement| SF = Managua north]] | |||

<hr> | |||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" |'''As San Francisco’s working class population of people of color rose dramatically from the 60s to the 70s, so did racism-fueled acts of police brutality and legal injustice. Several “third worldist” organizations, organizations inspired by 20th century revolutionary movements around the third world, sprung up in the Bay Area to combat this state-sponsored apparatus of oppression. These organizations, such as the Black Panther Party and Los Siete, are often painted as racially segregated groups. What is largely forgotten, however, is the cooperation between these groups and their united effort to protect and serve the vulnerable. ''' | |||

|} | |||

Many narratives of the Sixties trace the now familiar transition of a domestic agenda of civil rights, guided by a philosophy of nonviolence and liberal interracialism, into a more radical politics rooted in human rights, racial liberation, and militant demands for deep structural change. The events of May 1, 1969, readily demonstrate these dynamics. Yet, individual moments or historic flashpoints, such as this particular public gathering, equally reveal other important processes underway. New forms of community were being established and expressed. Much has been written, for instance, of how as Black nationalism gained greater currency within “the Movement,” challenging the tenets of liberal interracialism, Black and White activists reexamined and renegotiated the terms of their working relationship. Yet, remaining largely overlooked in this moment, and thereby lost to our collective memory, are the profound political and personal ties that existed ''between activists of color''. The recognition of this unique relationship has been obscured by the tendency to discuss racial matters (and movements) in strictly White-non-White terms. Yet, the boundaries separating these different struggles were extremely porous and a profound cross-fertilization of both ideas and people occurred which has not been fully recognized. Instead, many scholars (even on the Left) continue to paint these movements as narrowly nationalist. For sure, there were those that articulated a parochial “identity politics,” contributing to what Elizabeth “Betita” Martinez humorously calls the “Oppression Olympics.” Yet, not every political project exhibited this narrowness—least of all in the Bay Area. Instead, many articulated an identity and a set of politics that were rooted within a particular community, yet simultaneously opened outwards to embrace the struggles of others. | Many narratives of the Sixties trace the now familiar transition of a domestic agenda of civil rights, guided by a philosophy of nonviolence and liberal interracialism, into a more radical politics rooted in human rights, racial liberation, and militant demands for deep structural change. The events of May 1, 1969, readily demonstrate these dynamics. Yet, individual moments or historic flashpoints, such as this particular public gathering, equally reveal other important processes underway. New forms of community were being established and expressed. Much has been written, for instance, of how as Black nationalism gained greater currency within “the Movement,” challenging the tenets of liberal interracialism, Black and White activists reexamined and renegotiated the terms of their working relationship. Yet, remaining largely overlooked in this moment, and thereby lost to our collective memory, are the profound political and personal ties that existed ''between activists of color''. The recognition of this unique relationship has been obscured by the tendency to discuss racial matters (and movements) in strictly White-non-White terms. Yet, the boundaries separating these different struggles were extremely porous and a profound cross-fertilization of both ideas and people occurred which has not been fully recognized. Instead, many scholars (even on the Left) continue to paint these movements as narrowly nationalist. For sure, there were those that articulated a parochial “identity politics,” contributing to what Elizabeth “Betita” Martinez humorously calls the “Oppression Olympics.” Yet, not every political project exhibited this narrowness—least of all in the Bay Area. Instead, many articulated an identity and a set of politics that were rooted within a particular community, yet simultaneously opened outwards to embrace the struggles of others. | ||

| Line 37: | Line 47: | ||

''by Dr. Jason Ferreira, from his essay "With the Soul of a Human Rainbow," in the anthology "Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-78" (City Lights Foundation: 2011), edited by Chris Carlsson.'' | ''by Dr. Jason Ferreira, from his essay "With the Soul of a Human Rainbow," in the anthology "Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-78" (City Lights Foundation: 2011), edited by Chris Carlsson.'' | ||

[[Image:Ten Years small 87286100958430M.gif]] Find the book at [ | [[Image:Ten Years small 87286100958430M.gif]] Find the book at [https://citylights.com/foundation-books/10-years-that-shook-the-city-sf-68-78/ City Lights]! | ||

[[category:Dissent]] [[category:Mission]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:Latino]] [[category:Ten Years That Shook the City]] [[category:African-American]] | [[category:Dissent]] [[category:Mission]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:Latino]] [[category:Ten Years That Shook the City]] [[category:African-American]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:58, 23 November 2021

Historical Essay

by Dr. Jason Ferreira

Listen to an excerpt from "With the Soul of a Human Rainbow" read by author Dr. Jason Ferreira:

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/15TenYears--losSieteBlackPanthersThirdWorldismInSf" width="500" height="30" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

by mp3.

![]()

Previous stop: Women's self-health

Next Stop #16: SF = Managua north

| As San Francisco’s working class population of people of color rose dramatically from the 60s to the 70s, so did racism-fueled acts of police brutality and legal injustice. Several “third worldist” organizations, organizations inspired by 20th century revolutionary movements around the third world, sprung up in the Bay Area to combat this state-sponsored apparatus of oppression. These organizations, such as the Black Panther Party and Los Siete, are often painted as racially segregated groups. What is largely forgotten, however, is the cooperation between these groups and their united effort to protect and serve the vulnerable. |

Many narratives of the Sixties trace the now familiar transition of a domestic agenda of civil rights, guided by a philosophy of nonviolence and liberal interracialism, into a more radical politics rooted in human rights, racial liberation, and militant demands for deep structural change. The events of May 1, 1969, readily demonstrate these dynamics. Yet, individual moments or historic flashpoints, such as this particular public gathering, equally reveal other important processes underway. New forms of community were being established and expressed. Much has been written, for instance, of how as Black nationalism gained greater currency within “the Movement,” challenging the tenets of liberal interracialism, Black and White activists reexamined and renegotiated the terms of their working relationship. Yet, remaining largely overlooked in this moment, and thereby lost to our collective memory, are the profound political and personal ties that existed between activists of color. The recognition of this unique relationship has been obscured by the tendency to discuss racial matters (and movements) in strictly White-non-White terms. Yet, the boundaries separating these different struggles were extremely porous and a profound cross-fertilization of both ideas and people occurred which has not been fully recognized. Instead, many scholars (even on the Left) continue to paint these movements as narrowly nationalist. For sure, there were those that articulated a parochial “identity politics,” contributing to what Elizabeth “Betita” Martinez humorously calls the “Oppression Olympics.” Yet, not every political project exhibited this narrowness—least of all in the Bay Area. Instead, many articulated an identity and a set of politics that were rooted within a particular community, yet simultaneously opened outwards to embrace the struggles of others.

Thus, the “Free Huey” rally on May Day 1969 reveals a convergence of diverse, overlapping spheres of insurgency that collectively constituted a wider polycentric social movement. Rooted in the racialized, lived experiences faced by urban working-class communities of color in San Francisco, this “community of resistance” took shape around a pre-existing web of social and political relations found amongst diverse activists of color and was animated by, and articulated itself through, Third Worldist concepts (self-determination, anti-imperialism, and Third World unity). The Black Panther Party, the Red Guard Party, the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF), and United Native Americans emerged as a few organizational expressions of this larger polycentric movement.

As with the Black Panthers, the Red Guard Party, and other Third Worldist organizations, the issue of the criminal justice system, from police and prejudicial courts to prisons, played a formative role in Los Siete’s political development. Growing up in the Mission District during the 1950s, Alvarado recalls what life was like for Latina/o youth in the rapidly changing neighborhood:

It was like, man, you didn’t have a chance. You’re just nothing, nothing! You [were] just used, abused…and you didn’t have any so-called status…. A homeless guy once said that people tell me to go away…. He says, ‘Now, they don’t mean just go away, they mean go away, they mean disappear, they mean fall off the face of the earth and die. That’s what they mean by ‘go away.’ ’ That’s what it was like in the Mission.

Oscar Rios, the older brother of Jose Rios and another founder of Los Siete, attests to Alvarado’s memories, “It was very rough in the Mission. If you were hanging around, riding around, [the police] would stop you. Whatever they felt like doing to you, they would do it.”8 Paul Harris, a community-based lawyer who worked as “in-house” legal counsel for Los Siete de La Raza in later years, describes the San Francisco Police Department in a similar fashion:

The Panthers called it an occupation army (that’s the way they described it in Oakland) and that’s what it was; it was all White. And there was no understanding of what it meant to be living in the community…. People would get beat up in the Mission Station, in the basement, on a regular basis. The level of harassment was such that a policeman would stop a client of ours on the street, on Mission Street, just walk up to them and say ‘take off your shoes I want to see if you got any pot on you.’ Or, then there were these incredible police riots, where the police would just come in to peoples’ houses. They wanted you to know that they had the power. They had the power to do whatever they wanted.

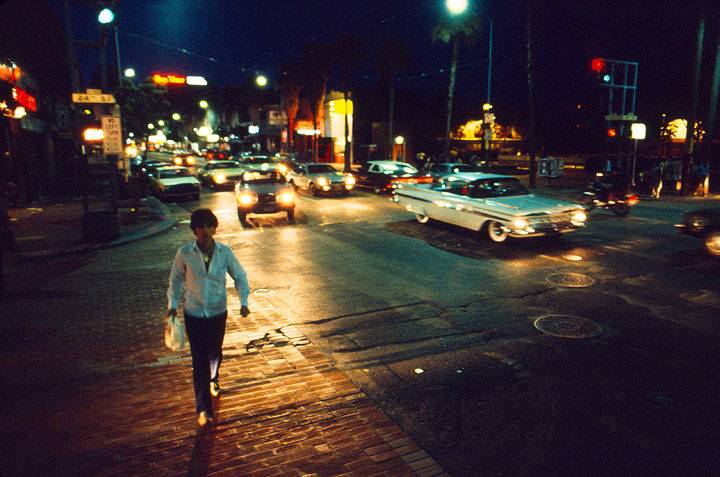

Mission and 24th during the Low Rider era, c. 1980.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

Some of this conflict clearly arose out of racist disapproval of the demographic changes occurring in San Francisco. By 1970, Whites only accounted for 57.2% of the City’s population, down from nearly 82% just a decade prior. More significant: the City’s youth population had become overwhelmingly “Third World.” With the increase of Latino, Black, Native American, and Asian-American families into the City—mostly poor and nearly all expecting their lives to improve—came a subsequent need and demand for jobs, housing, education, health care, recreational facilities, and greater political and cultural representation. San Francisco’s political economy, however, was undergoing a radical transformation itself, as a shrinking manufacturing and tax base directly impacted the provision of such necessary social services.9 Thus, aside from personal prejudice, these racial tensions between the police and members of the community reflected a deeper, more fundamental struggle over political, economic, and cultural power in an increasingly young, non-White city. Besides the public school system, the police formed the front-line of the City’s established institutions in dealing with these new realities and social pressures. Both failed miserably at containing these contradictions, as Third World student strikes shut down local educational institutions and police responded with ever-increasing levels of repression to preserve “law and order” and—in their eyes—to “keep the jungle at bay.”

It would be a mistake to claim that the idea of the Third World, as articulated by Los Siete and others in the Bay Area, was only an imitation of a more real political process underway in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Or, that activists of color carelessly imported ideas from the global arena into the local, simplistically drawing inspiration and imposing conclusions from classic revolutionary texts of the era, such as Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth, Albert Memmi’s The Colonizer and the Colonized, or Mao Tse-tung’s Red Book. Instead, as Karl Marx once observed, “it is not the consciousness of people which determines their existence, but on the contrary, it is their social existence which determines their consciousness.” The political analyses of different international revolutionaries were indeed influential, providing young radicals with a specific language and theoretical framework to interpret their realities, but the origins of the Third World consciousness in San Francisco—which activists creatively drew upon—was rooted deeper in the material conditions (and structural contradictions) that communities of color confronted in their post-war San Francisco neighborhoods.

by Dr. Jason Ferreira, from his essay "With the Soul of a Human Rainbow," in the anthology "Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-78" (City Lights Foundation: 2011), edited by Chris Carlsson.

Find the book at City Lights!

Find the book at City Lights!