Redevelopment in South of Market: Difference between revisions

m (Text replacement - "category:Gay and Lesbian" to "category:LGBTQI") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 137: | Line 137: | ||

[[Introduction to the SOMA|Prev. Document]] [[Former Residents of SOMA |Next Document]] | [[Introduction to the SOMA|Prev. Document]] [[Former Residents of SOMA |Next Document]] | ||

[[category:SOMA]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:redevelopment]] [[category:housing]] [[category:LGBTQI]] | [[category:SOMA]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:redevelopment]] [[category:housing]] [[category:LGBTQI]] [[category:Reclaiming San Francisco]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:50, 21 November 2021

Historical Essay

by Gayle S. Rubin

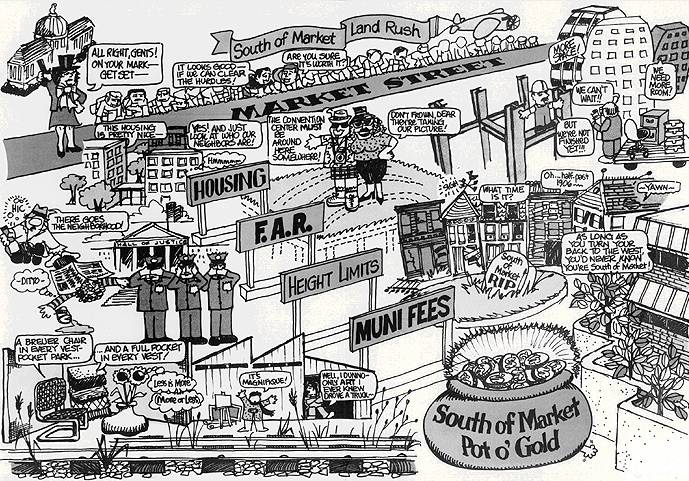

SPUR Graphic: The South Of Market Land Rush.

| Redevelopment in San Francisco began in the early 1950s, targeting so-called "blighted" areas for "slum clearance" and new construction. San Francisco’s South of Market (SOMA) redevelopment process was planned early and combined with hotelier Ben Swig's plans for the area, eventually led to today's Yerba Buena Gardens, itself a contested outcome. The Redevelopment juggernaut rolled over other neighborhoods in the 1960s and 1970s in addition to SOMA, but by the 1990s SOMA redevelopment resulted in conflicting social uses in the western South of Market, where gay leather bars persisted next to straight night clubs and Costco. |

"This land is too valuable to permit poor people to park on it."

--Justin Herman, Executive Director, San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, 1970 (cited in Chester Hartman, The Transformation of San Francisco, 1974)

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/CarloMiddioneOnWorkingForJustinHerman" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Former Redevelopment Agency official Carlo Middione describes getting hired at the Agency and what working for/with Justin Herman was like.

Video: Shaping San Francisco

The South of Market area for many years has been recognized as an area of blight producing a depressing, unhealthful, and unsafe living environment, retarding industrial development, and acting as a drain on the city treasury. This study of 86 blocks is concerned with the problems of blight and with ways and means of improving the area through the use of the redevelopment process. . . . The South of Market Area ranks among the most severely blighted sections of the city, along with Chinatown and the Western Addition. . . . [T]he conditions of blight are such as to be highly conducive to social disintegration, juvenile delinquency, and crime. . . . The present wasteful use of potentially valuable land must be stopped if the South of Market area is to become a well functioning part of the city's environment.

--Redevelopment Agency of the City and County of San Francisco 1952, 12

Dreams of urban renewal drove a great deal of postwar urban planning and politics. Redevelopment promised cleaner, more livable, and more prosperous cities; in practice, it often eliminated low-cost housing occupied by poor and working people and replaced light industry, warehousing, and wholesaling with high-rent offices, fancy hotels, and expensive restaurants. Urban renewal also provided opportunities for large and politically well-connected developers to amass huge fortunes, often subsidized by public funds.

Some of San Francisco's biggest redevelopment projects have been in the Western Addition, the Embarcadero just north of Market, and in the South of Market. The Western Addition, then one of the city's largest concentrations of African American residents, was targeted for redevelopment in 1954. In 1959, the old wholesale produce district and waterfront area north of Market were designated as the Golden Gateway/ Embarcadero/Lower Market Redevelopment Project Area. As early as 1953 large sections of the South of Market were approved for redevelopment by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. At that time, the South of Market still contained light industry. It housed the bus terminals and the cheap hotels for transients, seamen, and other single working men. While the main streets were lined with low-rent commercial businesses, a working-class residential population occupied the smaller side streets and alleys. Many of the charities serving the urban poor were located in the South of Market, which had a substantial concentration of homeless, drug-addicted, or alcoholic street people. The district, with its lower rents and physical proximity, was ideal for housing the service businesses for the large downtown firms. These factors made it a juicy redevelopment plum. (Hartman 1974, 1984; Hoover 1979)

In 1952 the Redevelopment Agency of the City and County in San Francisco released its first comprehensive proposal, which called for displacing the residential population in favor of more industry. Then, in 1954, today's Yerba Buena and Moscone Convention Center were foreshadowed when local developer Ben Swig unveiled a San Francisco Prosperity Plan. Swigs plan included a convention center, a sports stadium, and several high-rise office buildings. Much of that ambitious agenda has been accomplished, and the sports stadium now also looms as inevitable. One obvious prerequisite to South-of-Market development was the removal of the 4,000 residents and more than 700 small businesses. . . . In 1966, following final official approval of the plans by the Board of Supervisors, land acquisition and relocation began in earnest. (Hoover 1979, ix)

Then in 1969, local residents and owners formed Tenants and Owners in Opposition to Redevelopment (TOOR) and filed the first of the many lawsuits that delayed redevelopment and reshaped its ultimate manifestations. During the period of political and legal wrangling, the old neighborhood was significantly dismantled. Housing was demolished and entire streets disappeared. But the construction of new office towers and public buildings awaited the outcome of litigation, so the new neighborhood remained largely unrealized. In the interregnum, different kinds of residents and enterprises flowed into the disrupted niche. There were plenty of vacant buildings, both residential and commercial. Rents and land values were cheap, until speculation and resurgent redevelopment activity began to drive them higher. Street life at night was sparse. The streets emptied out when businesses closed and the daily work force departed. Parking at night was plentiful. The South of Market became a kind of urban frontier. The area began to attract artists looking for affordable studio space, musicians in search of practice venues, squatters who occupied the abandoned factories, and gay men. The relative lack of other nocturnal activity provided a kind of privacy, and urban nightlife that was stigmatized or considered disreputable could flourish in relative obscurity among the warehouses and deserted streets.

Redevelopment had suddenly escalated in the late 1970s. As Chester Hartman observes, South of Market redevelopment spanned the political lives of five mayors George Christopher, John Shelley, Joseph Alioto, George Moscone, and Dianne Feinstein. (Hartman 1984, 24) Moscone was elected in 1975. His administration was more oriented to neighborhood concern and consequences of downtown growth, and his appointments to the Planning Commission reflected these priorities. (xvii)

Dianne Feinstein became Mayor when George Moscone was assassinated by Dan White in 1978. Feinstein's friendlier stance toward development was reflected in an unprecedented building boom and in a marked increase in the pace of urban renewal in the South of Market. Among Dan White's legacies is a measure of responsibility for the accelerated Manhattanization of San Francisco in the 1980s. The convention center named after Moscone, who might have opposed its construction, was completed in 1981. That year, the San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR) released a report on South of Market development and held a conference to promote its findings. The flier for the conference showed Mayor Feinstein about to fire a starters pistol for the developers preparing to sprint across Market Street in quest of the South of Market Pot O' Gold. Sticking out from under the Pot O' Gold is the hand of someone crushed beneath, an apt image for the fate of the old neighborhood. Leather bars in old Victorian houses were not suited to compete with new high-rise, high-rent buildings or even the mid-level eateries and other enterprises that would service them. Long before AIDS was a factor, conversion to straighter, more respectable, more expensive bars and restaurants was well underway in the South of Market. Redevelopment is now rapidly invading and encircling the Folsom. At the northeast corner is the Moscone Center and the Yerba Buena complex, which includes two new museums and a performance center. More large civic projects and many private developments are planned. What remains of the leather bar area is within a few blocks of Yerba Buena. At the southeast corner is a large and growing retail complex which now includes Toys R Us, the Bed and Bath Superstore, Trader Joe's, and an entire city block devoted to a huge Price-Costco warehouse store. An Office Max store has recently opened just behind the San Francisco Eagle, one of the remaining leather bars. The back of the Costco parking lot faces the Eagle on one corner and the Lone Star, another leather bar, on the other. Shoppers laden with carts of paper towels and a year's supply of Windex are not a promising mix with gay men dressed in leather. The potential for conflict and violence along these ruptured territorial membranes is immense.

In October 1995, three men attacked and severely beat a patron leaving the Lone Star. He dragged himself over to the Eagle to obtain assistance, and his assailants were soon apprehended as they stood in line to get into a nearby music club, the DNA Lounge, which had once been a leather bar named Chaps. It is difficult to imagine how these businesses and populations can continue to coexist. The differences of scale between Costco and the leather bars in size, capital investment, and mayoral benediction are extreme. It is quite evident that if anything gives, it will not be Costco.

--excerpted from "The Miracle Mile, South of Market and Gay Male Leather 1962-1997" © 1997 by Gayle S. Rubin, in Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, Culture (City Lights Books, 1998)

REFERENCES

Averbach, Alvin. 1973. "San Francisco's South of Market District, 1858-1958: The Emergence of a Skid Row." California Historical Quarterly 52(3):196223.

Bean, Joseph W. 1988. "Changing Times South of Market." Advocate (California supplement) (29 March) 47.

Bérubé, Allan. 1984. "The History of the Baths." Coming Up! (December).

--1988. "Caught in the Storm: AIDS and the Meaning of Natural Disaster." Outlook (Fall).

--. 1993. "Dignity for All: The Role of Homosexuality in the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union (1930s-1950s)." Paper presented at Reworking American Labor History: Race, Gender, and Class conference. Madison.

--. 1996. "The History of the Bathhouses." In Dangerous Bedfellows, eds. Policing Public Sex: Queer Politics and the Future of AIDS Activism. Boston. South End Press.

--. Forthcoming. Shipping Out. New York: Houghton-Mifflin.

Bloomfield, Anne B. 19956. "A History of the California Historical Society's New Mission Street Neighborhood." California History (Winter 98).

Bolton, Ralph. 1992. "Aids and Promiscuity: Muddles in the Models of HIV Prevention." Medical Anthropology 14:145223.

Brandt, Allan M. 1988. "AIDS: From Social History to Social Policy." In Elizabeth Fee and Daniel M. Fox, eds.,

--. AIDS: The Burdens of History. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Caen, Herb. 1964. Column. San Francisco Chronicle (July 3).

Caffee, Mike. 1997. The Story of the Fe-Be's Statue, As Told by Its Sculptor, Mike Caffee. Unpublished manuscript.

Chauncey, George Jr. 1985. "Christian Brotherhood or Sexual Perversion? Homosexual Identities and the Construction of Sexual Boundaries in the World War One Era." Journal of Social History 19 (Winter):189211.

--. 1994. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay World, 1890-1940. New York: Basic Books

--.The Death of Leather. 1985. San Francisco Focus (November).

D'Emilio, John. 1983. Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

--. 1989a. "Gay Politics and Community in San Francisco Since World War II." In Duberman, Martin Bauml, Martha Vicinus, and George Chauncey, Jr., eds., Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past. New York: New American Library.

--. 1989b. "The Homosexual Menace: The Politics of Sexuality in Cold War America." In Kathy Peiss, Christina Simmons, and Robert Padgug, eds., Passion and Power: Sexuality in History. Philadelphia: Temple University.

Evans, Arthur (aka The Red Queen). 1982. Milk Milked. Letter to the editor, Bay Area Reporter (24 November) 6.

Freedman, Estelle. 1987. "Uncontrolled Desires: The Response to the Sexual Psychopath, 1920-1960." Journal of American History 74(1):83106.

Fritscher, Jack. 1991. "Artist Chuck Arnett: His Life/Our Times." In Mark Thompson, ed., Leatherfolk. Boston: Alyson.

Garber, Eric, and Willie Walker. 1997. "Queer Bars and Other Establishments in San Francisco." Gay and Lesbian Historical Society of Northern California. Unpublished data.

Gregersen, Edgar. 1983. Sexual Practices: The Story of Human Sexuality. New York: Franklin Watts.

Hartman, Chester. 1974. erba Buena: Land Grab and Community Resistance in San Francisco. San Francisco: Glide Publications.

--. 1984. The Transformation of San Francisco. Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Allanheld.

Hoover, Catherine. 1979. Introduction. In Ira Nowinski, No Vacancy: Urban Renewal and the Elderly. San Francisco: Carolyn Bean.

Issel, William, and Robert W. Cherney. 1986. San Francisco 1965-1932: Politics, Power, and Urban Development. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Knapp, Don. 1983. "A 20 Year Cycle." Bay Area Reporter (10 March) 13.

Mains, Geoff. 1984. Urban Aboriginals: A Celebration of Leathersexuality. San Francisco: Gay Sunshine Press.

Murray, Stephen O., and Kenneth W. Payne. 1988. "Medical Policy Without Scientific Evidence: The Promiscuity Paridigm and AIDS." California Sociologist 11(1/2):1354.

--. "Off-Beat Rough Toward Chic Very Fine." 1988. New York Times (September 15).

Patton, Cindy. 1985. Sex and Germs: The Politics of AIDS. Boston: South End Press.

Port of San Francisco. 1997. "Waterfront Design & Access: An Element of the Waterfront Land Use Plan." Draft (May 7).

Redevelopment Agency of the City and County of San Francisco. 1952. "The Feasibility of Redevelopment in the South of Market Area" (June 1).

Rubin, Gayle. 1994. "The Valley of the Kings: Leathermen in San Francisco, 1960-1990." Doctoral dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Michigan.

--. 1997. "Elegy for the Valley of the Kings: AIDS and the Leather Community in San Francisco, 1981-1996." In Martin Levine, Peter Nardi, and John Gagnon, eds., In Changing Times: Gay Men and Lesbians Encounter HIV/AIDS. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Shilts, Randy. 1987. And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic. New York: St. Martins Press.

Starr, Kevin. 1995-6. "South of Market and Bunker Hill." California History (Winter).

Thompson, Mark. 1982. "Folsom Street." Advocate (8 July) 2831, 57.

--. 1991. Leatherfolk: Radical Sex, People, Politics, and Practice. Boston: Alyson.

Triechler, Paula. 1988. "AIDS, Homophobia, and Biomedical Discourse: An Epidemic of Signification." In Douglas Crimp, Cultural Analysis, Cultural Activism.

Walker, Willie. 1997. "Gay Bars, Bathhouses and Restaurants in San Francisco 1930-1969." Gay and Lesbian Historical Society of Northern California. Unpublished data, charts, and graphs.

Welch, Paul, and Bill Eppridge (photographer). 1964. "Homosexuality in America." Life (26 June) 66-80.