Twist: Difference between revisions

(Wrote an Abstract) |

No edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

[[Image:Twist-4-heads.jpg]] | [[Image:Twist-4-heads.jpg]] | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | {| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | ||

| Line 36: | Line 37: | ||

[[Rigo 90-something | Prev. Document]] [[Reminisce | Next Document]] | [[Rigo 90-something | Prev. Document]] [[Reminisce | Next Document]] | ||

[[category:Public Art]] [[category:1980s]] | [[category:Public Art]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:Reclaiming San Francisco]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:44, 21 November 2021

Historical Essay

by Timothy W. Drescher

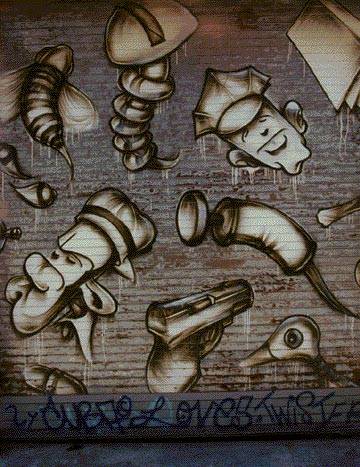

Clarion Alley, Twist Mural Detail

| Graffiti artist Twist hopes to engage the public and encourage non-conventional thought by using humor in his art and contesting traditions of other graffiti artists and muralists. His art rejects realism by spontaneously claiming private and public spaces, thus challenging mainstream conceptions of institutions and traditionalism by turning what is static into an "instant dialogue." |

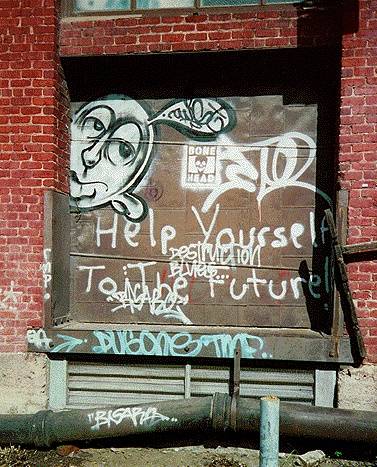

Barry McGee (aka 'Twist') explains that he "never wanted my graffiti to be absolute, 'this is the way it is.' I wanted to bring a smile--empty shirts with ties for example. I want a dialogue, so the most effective work is humorous because it engages the viewer, as does leaving the meaning a little bit unclear." For McGee, a plain drawing style makes his work accessible, and positive because it is non-threatening. This allows him to develop irony simply by means of where geographically in the city, and urbanistically relative to other buildings, a figure is placed. Figures looking world weary elicit wry smiles when placed where they can be seen by freeway commuters, for instance.

In McGee's case, the comic book style developed somewhat differently. He favors a monochrome style which grows out of the two color throw-ups (large, balloon lettering outlines with a single color filling in the letters) of spray can graffiti tags. This style, of course, in its simplicity allows for spontaneity, which in McGee's case enables him to work quickly in non-permissional circumstances. As it turns out, he values the spontaneity in any case, feeling that the sense of immediacy contributes significantly to the meaning of his figures. The drips falling from the bottom of his figures announces both the spontaneity and his subtle challenge to graffiti writers, among whom no drips is an unstated rule.

McGee's spontaneity, which he retains even in permissional projects, can be compared with the Ramona Parra Brigade in Chile during the Pinochet regime, which developed a quick style of painting because of the very real dangers of being caught by the military thugs and beaten, tortured, certainly jailed. Although McGee works alone, and there is not the same political immediacy that there was in the Chilean murals, and the consequences of being caught spray painting are not as severe in this country (although reports of police beatings are common enough among writers), it is still preferable not to be caught.

Perhaps the clearest departure from traditional murals is the rejection of realism. Traditional murals are thoroughly planned. Indeed, the planning process is often a key element in the subversion by the art form in that its provision of a touch of genuinely democratic experience runs so counter to the normal experience of the murals audiences. But the spontaneous spray can artists contest for public space simply by doing it, by taking it and then leaving it up to "the authorities" to challenge their appropriation. This contestation has a more dynamic aspect to it than traditional murals precisely because it is an ongoing process of challenge and response played out publicly on the walls of public space, albeit often on private property. Some graffiti art thus becomes, as McGee puts it, a type of performance art, whereas traditional murals exist more as artworks, as static expressions (except for their manipulation of perspectives and the relationships to their visual environments embodied in their designs).

For McGee, graffiti may be a kind of "striking back" at any excess or injustice of any powerful institution. It thus creates an "instant dialogue," which is carried out in actions, if not verbally. Traditional murals may oppose institutional positions (such as U.S. intervention in Central America, in the Balmy murals, or the marginalization of ethnic cultures in any number of "ethnic pride" murals), but such dialogue is rare unless provided by the mural itself, as in the case of a 1995 Chicago work by Olivia Gude, Where We Come From, Where Were Going, which incorporates substantial portions of text into the mural, quoting passersby to the site who comprise the figures represented in the mural.

Oddly for a style that communicates so readily a joie de vivre, McGee's figures are clearly world weary. This offers yet another avenue for passersby to identify with, and, again, contrasts with the generally high-energy figures of traditional murals. The tendency of McGee's pieces to bring a smile to the faces of his audience also illuminates the lack of humor in traditional murals.

--Excerpted from the essay "Street Subversion: The Political Geography of Graffiti and Murals" by Timothy W. Drescher in Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, Culture City Lights Books, 1998.

Twist art (the head in the upper left) in a doorway