Civic Beautification: Difference between revisions

Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' ''by William Issel and Robert Cherny'' Anti-Vice Campaigns in Early..." |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

''by William Issel and Robert Cherny'' | ''by William Issel and Robert Cherny'' | ||

[[Anti-Vice Campaigns in Early 20th Century San Francisco|continued from part | [[Anti-Vice Campaigns in Early 20th Century San Francisco|continued from part three]] | ||

[[Image:tendrnob$civic-center-1930.jpg]] | [[Image:tendrnob$civic-center-1930.jpg]] | ||

Revision as of 15:46, 19 November 2021

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

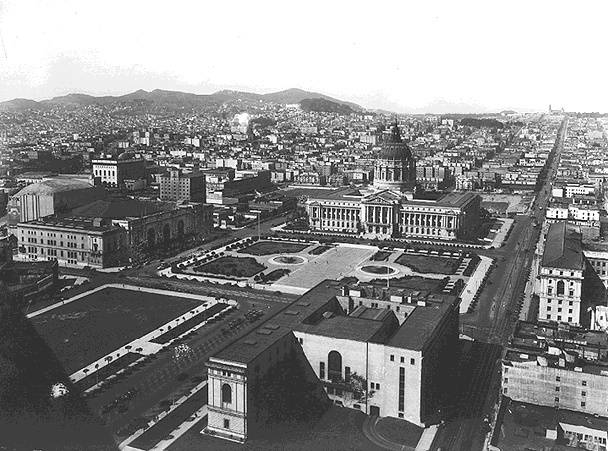

New City Hall, shown here around 1930, with the Civic Auditorium at left and Main Library lower right.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

San Francisco was no exception. The force of the “City Beautiful” movement struck San Francisco between the late 1890s and 1910 when James Phelan and the Association for the Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco worked to implement their belief that the redesign of the city's physical environment would increase social harmony and enhance San Francisco’s prosperity and growth. Phelan believed that San Francisco needed statues, monuments, parks, parkways, great plazas at the focal points of grand boulevards, and stately public buildings in the Beaux Arts style in order to dramatize its potential as “the capital of an empire.”(32) Phelan’s convictions grew out of his experiences as president of the Bohemian Club and the San Francisco Art Association, his vice-presidency of the California World’s Fair Commission in 1893, and his service as the manager of the California exhibition at the Chicago World’s Fair. He also helped inaugurate the Midwinter Fair in San Francisco (1894).

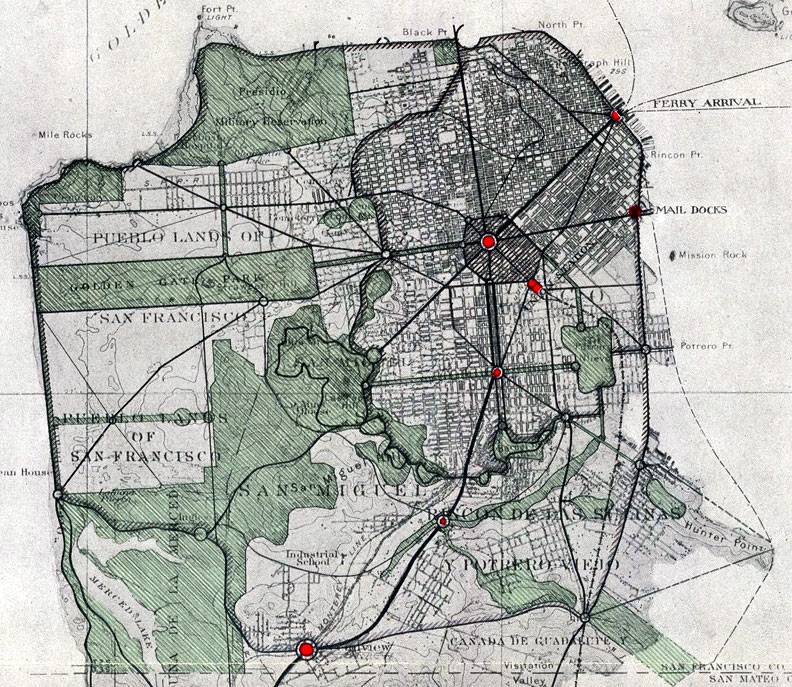

In 1899 Phelan unsuccessfully put his influence as mayor behind a proposal to extend the Panhandle of Golden Gate Park downtown to the intersection of Van Ness Avenue and Market Street. Five years later, no longer mayor, Phelan and the presidents of the Bohemian Club, the Pacific Union Club, and the Art Association organized the Adornment Association, which published a list of planning objectives for the city. The formation of the association coincided with Reuben Hale’s proposal that San Francisco host a world’s fair and with growing public discussion within the business community about San Francisco’s need to maintain its attractiveness to tourists and prospective investors in the face of competition from southern California. Even before Phelan began his term as first president of the association, he asked Daniel H. Burnham, the nation’s leading city planner, to provide a comprehensive design as the basis for a campaign to secure public support for an “imperial” San Francisco along the lines of Athens, Paris, and Washington, D.C.(33) Judd Kahn has shown that “founders of the association, by and large, were longtime San Franciscans and members of the city’s social and economic upper crust.” The Burnham plan that they commissioned included measures to reduce traffic congestion, increase commercial efficiency, and enhance aesthetic pleasure. In addition, elements in the plan provided citizens, in the view of the architect himself, “a lesson of order and system, and its influence on the masses cannot be overestimated.”(34)

A version of the Burnham Plan's reorganization of urban arterials and street patterns.

Burnham’s belief in the uplifting potential of his proposals never received a test. Neither the strongest supporters of the plan nor its staunchest opponents would agree that city government ought to exercise the sweeping powers over private property necessary for the implementation of a comprehensive city plan. Unwilling to trust the electoral process because they could not control the outcome, Phelan and his fellow reformers probably decided “to leave the Burnham plan as an inspiring ideal at which to aim [rather] than to try to enact it by a political process that might weaken the very basis of social stability.”(35)

Although the Burnham plan had come and gone by 1910, well-to-do San Franciscans continued to support policies designed to provide cultural uplift by contributing to the establishment and the support of public museums, art institutes, libraries, and concert orchestras. Like Phelan and the Adornment Association, and like their counterparts in New York, Boston, and Chicago, San Francisco’s leading cultural philanthropists turned to cultural policy primarily for social purposes. As Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz has put it in describing the Chicago case: “Disturbed by social forces they could not control and filled with idealistic notions of culture, these businessmen saw in the museum, the library, the symphony orchestra, and the university a way to purify their city and to generate a civic renaissance.”(36)

In San Francisco, as elsewhere, only a small proportion of individuals carried out the bulk of the cultural philanthropy. In San Francisco, as elsewhere, philanthropists exuded self-confidence as they assumed leadership roles that they regarded as properly their own. They turned to cultural policy with certainty in their conviction that the best people should shape the city’s culture rather than with anxiety about their status as arbiters of taste.(37) San Francisco did depart from the norm in the relatively large proportion of Roman Catholics and Jews who played key roles in the development of major cultural institutions. Chinese, Japanese, and black San Franciscans, however, played no more active a role in shaping the city’s cultural policies than they did in other American cities, and racial exclusion remained the norm throughout the period in this as in other aspects of public policy formation.(38)

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 5 “Culture and Moral Order”