Employment of People 1849: Difference between revisions

(PC) |

(moved byline to top) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Primary Source</font></font> </font>''' | '''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Primary Source</font></font> </font>''' | ||

—from ''Annals of San Francisco, 1855'' | |||

[[Image:annals$charcoal-vendor.jpg]] | [[Image:annals$charcoal-vendor.jpg]] | ||

| Line 11: | Line 13: | ||

All things seemed in the utmost disorder. The streets and passages, such as they were, and the inside of tents and houses, were heaped with all sorts of goods and lumber. There seemed no method in any thing. People bustled and jostled against each other, bawled, railed and fought, cursed and swore, sweated and labored lustily, and somehow the work was done. A spectator would have imagined the confusion inextricable, but soon had reason to change his opinion. Every- body was busy, and knew very well what he himself had to do. Heaps of goods disappeared, as if by magic, and new heaps appeared in their place. Where there was a vacant piece of ground one day, the next saw it covered with half a dozen tents or shanties. Horses, mules and oxen forced a way through, across, and over every obstruction in the streets; and men waded and toiled after them. Hundreds of rude houses and tents were daily in the course of erection; they nestled between the sand-hills, covered their tops, and climbed the north and west of the town. | All things seemed in the utmost disorder. The streets and passages, such as they were, and the inside of tents and houses, were heaped with all sorts of goods and lumber. There seemed no method in any thing. People bustled and jostled against each other, bawled, railed and fought, cursed and swore, sweated and labored lustily, and somehow the work was done. A spectator would have imagined the confusion inextricable, but soon had reason to change his opinion. Every- body was busy, and knew very well what he himself had to do. Heaps of goods disappeared, as if by magic, and new heaps appeared in their place. Where there was a vacant piece of ground one day, the next saw it covered with half a dozen tents or shanties. Horses, mules and oxen forced a way through, across, and over every obstruction in the streets; and men waded and toiled after them. Hundreds of rude houses and tents were daily in the course of erection; they nestled between the sand-hills, covered their tops, and climbed the north and west of the town. | ||

Latest revision as of 11:57, 17 April 2021

Primary Source

—from Annals of San Francisco, 1855

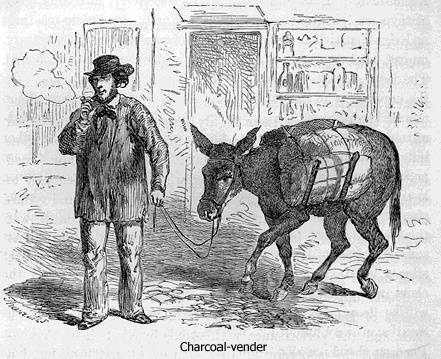

Charcoal Vendor

In those miserable apologies for houses, surrounded by heaps and patches of filth, mud and stagnant water, the strange mixed population carried on business, after a fashion. It is not to be supposed that people could or did manage matters in the strict orderly manner of older communities. Very few were following that particular business to which they had been bred, or for which they were best fitted by nature. Every immigrant, on landing at San Francisco, became a new man in his own estimation, and was prepared to undertake anything or any piece of business whatsoever. And truly he did it; but it was with a deal of noise, bustle and unnecessary confusion. The great recognized orders of society were tumbled topsy-turvy.

Doctors and dentists became draymen, or barbers, or shoe-blacks; lawyers, brokers and clerks, turned waiters, or auctioneers, or perhaps butchers; merchants tried laboring and lumping, while laborers and jumpers changed to merchants. The idlest might be tempted, and the weakest were able, to do something--to drive a nail in frame buildings, lead a burdened mule, keep a stall, ring a bell or run a message. Adventurers, merchants, lawyers, clerks, tradesmen, mechanics, and every class in turn kept lodging-houses, eating and drinking houses, billiard rooms and gambling saloons, or single tables at these; they dabbled in "beach and water lots," fifty-vara blocks, and new town allotments over the whole country; speculated in flour, beef, pork and potatoes; in lumber and other building materials; in dry goods and soft, hard goods and wet; bought and sold, wholesale and retail, and were ready to change their occupation and embark in some new nondescript undertaking after two minutes' consideration.

All things seemed in the utmost disorder. The streets and passages, such as they were, and the inside of tents and houses, were heaped with all sorts of goods and lumber. There seemed no method in any thing. People bustled and jostled against each other, bawled, railed and fought, cursed and swore, sweated and labored lustily, and somehow the work was done. A spectator would have imagined the confusion inextricable, but soon had reason to change his opinion. Every- body was busy, and knew very well what he himself had to do. Heaps of goods disappeared, as if by magic, and new heaps appeared in their place. Where there was a vacant piece of ground one day, the next saw it covered with half a dozen tents or shanties. Horses, mules and oxen forced a way through, across, and over every obstruction in the streets; and men waded and toiled after them. Hundreds of rude houses and tents were daily in the course of erection; they nestled between the sand-hills, covered their tops, and climbed the north and west of the town.