Moving Victorians in the Fillmore: Difference between revisions

added text resulting from Stanford assignment to fill out an Unfinished History |

m Protected "Moving Victorians in the Fillmore" ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite)) |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

''by Danielle Rubin, 2013'' | ''by Danielle Rubin, 2013'' | ||

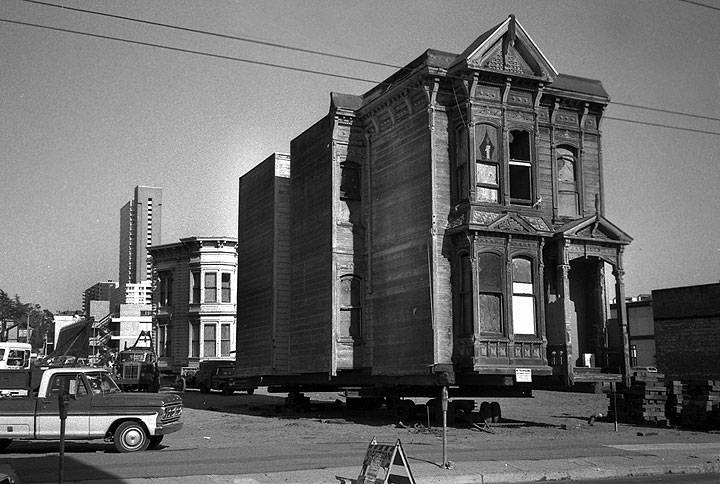

'' | [[Image:1976-victorian-on-stilts-now-moved-and-restored-Dave-Glass.jpg]] | ||

''Photo © [http://www.flickr.com/photos/daveglass/ Dave Glass], 1976-77'' | |||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" |'''In the mid-1970s the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency stopped the wholesale destruction of venerable Victorian buildings. Instead, they picked them up and moved them around the neighborhood. One well-known example is the building that housed [[Jimbo's Bop City|Jimbo's Bop City]] on Post Street which was moved to its current location on Fillmore near Sutter, housing Marcus Books.''' | |||

|} | |||

''' | <font size=4>'''Western Addition redevelopment galvanizes opposition'''</font size><br> | ||

In 1947, the San Francisco Planning Department issued a report with plans for [[Fillmore Redevelopment|redevelopment in the Western Addition]], including [[The Fillmore: Black SF|the Fillmore]]. The district had become a [[Fillmore Cultural Capital|center of jazz]] and grand Victorian architecture, but overcrowding and the high proportion of low-income black families led critics to declare the area as blighted. Besides, proximity to the financial district made the Fillmore ideal for new apartment buildings and high-rises. The San Francisco Redevelopment Agency promised to replace what was “considered a slum with a nice new neighborhood.”(1) | |||

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/CarloMiddioneOnEnidSalesAndMovingVictorians" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe> | |||

'''Former Redevelopment Agency official Carlo Middione describes the work of a key group, including [[Enid Sales, Preservationist|Enid Sales]], in the Agency to preserve some of the old Victorians in the Western Addition by getting them moved to new locations.''' | |||

''Video: Shaping San Francisco'' | |||

The redevelopment occurred in two phases: the A-1 and the A-2 projects. The A-1 project cleared entire blocks beginning in 1956, and quickly, the destruction of the neighborhood’s character, including its architecture, was apparent. As a result, when the [[The ILWU and Western Addition Redevelopment A-2|A-2 project]] was announced in 1964, there was more opposition by residents, sympathizers, and pioneers of historic preservation.(2) These protestors had a few successes, including the relocation of twelve Victorians homes; but ultimately, 2,500 Victorians were demolished.(3) Today, “there is hardly an example of noteworthy architecture in the area, particularly considering what the new buildings replaced..."(4) | |||

<font size=4>'''Rise of architectural preservation to save the Victorians'''</font size><br> | |||

[[Image:1977-Victorian-on-stilts-to-be-moved-Dave-Glass.jpg]] | [[Image:1977-Victorian-on-stilts-to-be-moved-Dave-Glass.jpg]] | ||

''Photo © [http://www.flickr.com/photos/daveglass/ Dave Glass], 1976-77'' | |||

Before the 1960s, rehabilitation and preservation of architecture was not the norm. In addition to demolition, the legacy of Victorian architecture was threatened by a “modernizing trend” of careless alterations and additions.(5,6) However, a newfound respect for the city’s architectural heritage began concurrent with the Fillmore’s redevelopment. In 1961, the Redevelopment Agency gained a new objective: to preserve buildings of architectural or historic significance. This was a remarkable shift, considering the Redevelopment Agency was in charge of the A-1 and A-2 projects. In fact, the program for the A-2 project included the rehabilitation of Victorian houses west of Fillmore Street—though this did not prevent the destruction of many others.(7) | |||

<font size=4>Heritage saves twelve Victorian homes</font size><br> | During the 1960s, the city’s first architectural surveys were performed, the Planning Department added preservation goals, and the Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board was created.(8) Yet, Charles Hall Page and Harry Miller were still unsatisfied. Landmark buildings needed greater protection, so in 1971, Page and Miller created San Francisco Architectural Heritage. They hoped to preserve the city’s architectural legacy, starting with the Victorian houses in the Western Addition.(9) | ||

<font size=4>'''Heritage saves twelve Victorian homes'''</font size><br> | |||

[[Image:1977-House-Movers-Dave-Glass.jpg]] | [[Image:1977-House-Movers-Dave-Glass.jpg]] | ||

With aid from the Landmarks Board, Heritage negotiated with the Redevelopment Agency to identify twelve Victorian houses that were scheduled for demolition but could be saved.10 The Redevelopment Agency agreed to sell, rather than demolish, the houses if they were moved to a new location.11 Thus, at a public auction in the summer of 1972, Heritage entered minimum bids as a purchaser of last resort and gained ownership of the houses. While waiting for the move, Heritage and the Redevelopment Agency began to identify new homeowners, who agreed to rehabilitate and help conserve the homes.12 | ''Photo © [http://www.flickr.com/photos/daveglass/ Dave Glass], 1976-77'' | ||

With aid from the Landmarks Board, Heritage negotiated with the Redevelopment Agency to identify twelve Victorian houses that were scheduled for demolition but could be saved.(10) The Redevelopment Agency agreed to sell, rather than demolish, the houses if they were moved to a new location.(11) Thus, at a public auction in the summer of 1972, Heritage entered minimum bids as a purchaser of last resort and gained ownership of the houses. While waiting for the move, Heritage and the Redevelopment Agency began to identify new homeowners, who agreed to rehabilitate and help conserve the homes.(12) | |||

In November 1974, the houses were moved in groups of four over three weekends. Most of the houses started from the block that currently houses Opera Plaza and traveled approximately one mile to their final destinations. Eight of the homes joined existing Victorians to form the Beiderman Place Historic Area. | In November 1974, the houses were moved in groups of four over three weekends. Most of the houses started from the block that currently houses Opera Plaza and traveled approximately one mile to their final destinations. Eight of the homes joined existing Victorians to form the Beiderman Place Historic Area. | ||

| Line 33: | Line 46: | ||

[[Image:1976-Victorian-on-stilts-being-moved-Dave-Glass.jpg]] | [[Image:1976-Victorian-on-stilts-being-moved-Dave-Glass.jpg]] | ||

''Photo © [http://www.flickr.com/photos/daveglass/ Dave Glass], 1976-77'' | |||

Onlookers compared the move to a military operation. Utility crews accompanied the houses to move power and telephone lines, cut trolley wires, and remove streetlights. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, there were also thirty motorcycle police and thirty tow trucks to clear the path.(13) As they moved, the houses appeared like great ships “moving through some inland waterway.”(14) | |||

<font size=4>After the move</font size><br> | This was the largest moving project in San Francisco’s history. It took eighteen months to reach an agreement, twenty months to begin relocation, and one month to move the houses, but the Victorians were saved.(15) | ||

<font size=4>'''After the move'''</font size><br> | |||

[[Image:1977-backing-in-3-story-victorian-Dave-Glass.jpg]] | [[Image:1977-backing-in-3-story-victorian-Dave-Glass.jpg]] | ||

The relocation of the Victorian homes was not without its problems. First, many of the homes were moved to lots where other Victorians had been demolished—a bittersweet victory.16 Second, relocation of individual buildings was not the ideal solution. Relocation did not preserve the character of the area, and a piecemeal strategy tends to be less effective than a comprehensive one.18 Third, the new homeowners and the members of the Landmarks Board, Heritage, and the Redevelopment Agency were predominately from the white, upper middle class.19 The homes may have been saved, but there was [[WACO Attacks Redevelopment|resentment among the Fillmore’s low-income black residents]].20 | ''Photo © [http://www.flickr.com/photos/daveglass/ Dave Glass], 1976-77'' | ||

The relocation of the Victorian homes was not without its problems. First, many of the homes were moved to lots where other Victorians had been demolished—a bittersweet victory.(16) Second, relocation of individual buildings was not the ideal solution. Relocation did not preserve the character of the area, and a piecemeal strategy tends to be less effective than a comprehensive one.(18) Third, the new homeowners and the members of the Landmarks Board, Heritage, and the Redevelopment Agency were predominately from the white, upper middle class.(19) The homes may have been saved, but there was [[WACO Attacks Redevelopment|resentment among the Fillmore’s low-income black residents]].(20) | |||

Yet amid the great tragedy of the Fillmore’s redevelopment, newspaper articles and books portrayed the move as an exciting event. In fact, newspaper articles appeared around the country, as far away as the east coast, and many people watched the relocation efforts. | Yet amid the great tragedy of the Fillmore’s redevelopment, newspaper articles and books portrayed the move as an exciting event. In fact, newspaper articles appeared around the country, as far away as the east coast, and many people watched the relocation efforts. | ||

Nonetheless, the relocation of twelve Victorian homes was a great victory for architectural preservation. The young organization gained a high level of visibility due to national press coverage, winning public support for future preservation efforts.21 | Nonetheless, the relocation of twelve Victorian homes was a great victory for architectural preservation. The young organization gained a high level of visibility due to national press coverage, winning public support for future preservation efforts.(21) | ||

'''Footnotes''' | |||

1) Peter Booth Wiley, National Trust Guide – San Francisco: America’s Guide for Architecture and History Travelers (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2000), p. 284-290 | 1) Peter Booth Wiley, National Trust Guide – San Francisco: America’s Guide for Architecture and History Travelers (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2000), p. 284-290 | ||

Latest revision as of 13:28, 22 February 2021

Historical Essay

by Danielle Rubin, 2013

Photo © Dave Glass, 1976-77

| In the mid-1970s the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency stopped the wholesale destruction of venerable Victorian buildings. Instead, they picked them up and moved them around the neighborhood. One well-known example is the building that housed Jimbo's Bop City on Post Street which was moved to its current location on Fillmore near Sutter, housing Marcus Books. |

Western Addition redevelopment galvanizes opposition

In 1947, the San Francisco Planning Department issued a report with plans for redevelopment in the Western Addition, including the Fillmore. The district had become a center of jazz and grand Victorian architecture, but overcrowding and the high proportion of low-income black families led critics to declare the area as blighted. Besides, proximity to the financial district made the Fillmore ideal for new apartment buildings and high-rises. The San Francisco Redevelopment Agency promised to replace what was “considered a slum with a nice new neighborhood.”(1)

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/CarloMiddioneOnEnidSalesAndMovingVictorians" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Former Redevelopment Agency official Carlo Middione describes the work of a key group, including Enid Sales, in the Agency to preserve some of the old Victorians in the Western Addition by getting them moved to new locations.

Video: Shaping San Francisco

The redevelopment occurred in two phases: the A-1 and the A-2 projects. The A-1 project cleared entire blocks beginning in 1956, and quickly, the destruction of the neighborhood’s character, including its architecture, was apparent. As a result, when the A-2 project was announced in 1964, there was more opposition by residents, sympathizers, and pioneers of historic preservation.(2) These protestors had a few successes, including the relocation of twelve Victorians homes; but ultimately, 2,500 Victorians were demolished.(3) Today, “there is hardly an example of noteworthy architecture in the area, particularly considering what the new buildings replaced..."(4)

Rise of architectural preservation to save the Victorians

Photo © Dave Glass, 1976-77

Before the 1960s, rehabilitation and preservation of architecture was not the norm. In addition to demolition, the legacy of Victorian architecture was threatened by a “modernizing trend” of careless alterations and additions.(5,6) However, a newfound respect for the city’s architectural heritage began concurrent with the Fillmore’s redevelopment. In 1961, the Redevelopment Agency gained a new objective: to preserve buildings of architectural or historic significance. This was a remarkable shift, considering the Redevelopment Agency was in charge of the A-1 and A-2 projects. In fact, the program for the A-2 project included the rehabilitation of Victorian houses west of Fillmore Street—though this did not prevent the destruction of many others.(7)

During the 1960s, the city’s first architectural surveys were performed, the Planning Department added preservation goals, and the Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board was created.(8) Yet, Charles Hall Page and Harry Miller were still unsatisfied. Landmark buildings needed greater protection, so in 1971, Page and Miller created San Francisco Architectural Heritage. They hoped to preserve the city’s architectural legacy, starting with the Victorian houses in the Western Addition.(9)

Heritage saves twelve Victorian homes

Photo © Dave Glass, 1976-77

With aid from the Landmarks Board, Heritage negotiated with the Redevelopment Agency to identify twelve Victorian houses that were scheduled for demolition but could be saved.(10) The Redevelopment Agency agreed to sell, rather than demolish, the houses if they were moved to a new location.(11) Thus, at a public auction in the summer of 1972, Heritage entered minimum bids as a purchaser of last resort and gained ownership of the houses. While waiting for the move, Heritage and the Redevelopment Agency began to identify new homeowners, who agreed to rehabilitate and help conserve the homes.(12)

In November 1974, the houses were moved in groups of four over three weekends. Most of the houses started from the block that currently houses Opera Plaza and traveled approximately one mile to their final destinations. Eight of the homes joined existing Victorians to form the Beiderman Place Historic Area.

Photo © Dave Glass, 1976-77

Onlookers compared the move to a military operation. Utility crews accompanied the houses to move power and telephone lines, cut trolley wires, and remove streetlights. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, there were also thirty motorcycle police and thirty tow trucks to clear the path.(13) As they moved, the houses appeared like great ships “moving through some inland waterway.”(14)

This was the largest moving project in San Francisco’s history. It took eighteen months to reach an agreement, twenty months to begin relocation, and one month to move the houses, but the Victorians were saved.(15)

After the move

Photo © Dave Glass, 1976-77

The relocation of the Victorian homes was not without its problems. First, many of the homes were moved to lots where other Victorians had been demolished—a bittersweet victory.(16) Second, relocation of individual buildings was not the ideal solution. Relocation did not preserve the character of the area, and a piecemeal strategy tends to be less effective than a comprehensive one.(18) Third, the new homeowners and the members of the Landmarks Board, Heritage, and the Redevelopment Agency were predominately from the white, upper middle class.(19) The homes may have been saved, but there was resentment among the Fillmore’s low-income black residents.(20)

Yet amid the great tragedy of the Fillmore’s redevelopment, newspaper articles and books portrayed the move as an exciting event. In fact, newspaper articles appeared around the country, as far away as the east coast, and many people watched the relocation efforts.

Nonetheless, the relocation of twelve Victorian homes was a great victory for architectural preservation. The young organization gained a high level of visibility due to national press coverage, winning public support for future preservation efforts.(21)

Footnotes

1) Peter Booth Wiley, National Trust Guide – San Francisco: America’s Guide for Architecture and History Travelers (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2000), p. 284-290

2) Ibid.

3) Leslie Fulbright, “Sad chapter in Western Addition history ending,” San Francisco Chronicle, 21 July 2008, http://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Sad-chapter-in-Western-Addition-history-ending-3203302.php.

4) Peter Booth Wiley, National Trust Guide, p. 291.

5) Rand Richards, Historic San Francisco: A Concise History and Guide (San Francisco: Heritage House Publishers, 1991, 1999), p. 248

6) San Francisco Planning Department, “Brief History of the Historic Preservation Movement in the United States and in San Francisco,” Preservation Bulletin, no. 14 (2003, 2011)

7) Peter Booth Wiley, National Trust Guide, p. 290-291.

8) Michael R. Corbett, Port City: The History and Transformation of the Port of San Francisco, 1848-2010 (San Francisco: San Francisco Architectural Heritage, 2011), p. 12-15

9) Peter Booth Wiley, National Trust Guide, p. 292.

10) San Francisco Architectural Heritage, “The Dawn of Heritage: Relocating Western Addition Victorians,” Heritage Newsletter, vol. XXIV, no. 1 (1996)

11) Peter Booth Wiley, National Trust, p. 292.

12) Michael R. Corbett, Port City, p. 15.

13) Karen Liberatore, “Moving Story of a Classic Victorian,” San Francisco Chronicle, 1 July 21 1992, http://iw.newsbank.com/iw-search/we/InfoWeb?p_action=doc&p_theme=aggdocs&p_topdoc=1&p_docnum=1&p_sort=YMD_date:D&p_product=AWNB&p_docid=0EB4F41EF761D2D5&p_text_direct-0=document_id=(%200EB4F41EF761D2D5%20)&s_lang=en-US&p_nbid=A68F52HNMTM2NzAwMTU3NC4yMjM3MDY6MToxMDoxMjguMTIuMC4w.

14) San Francisco Architectural Heritage, “The Dawn of Heritage.”

15) Ibid.

16) Chester Hartman, City for Sale: The Transformation of San Francisco (Ewing, NJ: University of California Press, 2002), p. 309.

17) Peter Booth Wiley, National Trust, p. 292.

18) Michael R. Corbett, Port City, p. 15.

19) Chester Hartman, City for Sale, p. 309.

20) Peter Booth Wiley, National Trust, p. 292.

21) Michael R. Corbett, Port City, p. 15.