Thomas Starr King: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

[[Image:View southeast across Temple Emanuel and Union Square c 1867 wnp37.0067.jpg]] | [[Image:View southeast across Temple Emanuel and Union Square c 1867 wnp37.0067.jpg]] | ||

'''View southeast | '''View southeast across Union Square, Temple Emanu-el in foreground and First Unitarian Church to the right and behind, circa 1867.''' | ||

''Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org, wnp37.0067.jpg'' | ''Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org, wnp37.0067.jpg'' | ||

Latest revision as of 15:42, 8 November 2020

Historical Essay

by Arnold Wood, October 2020

Reprinted from OpenSFHistory.org, courtesy Western Neighborhoods Project.

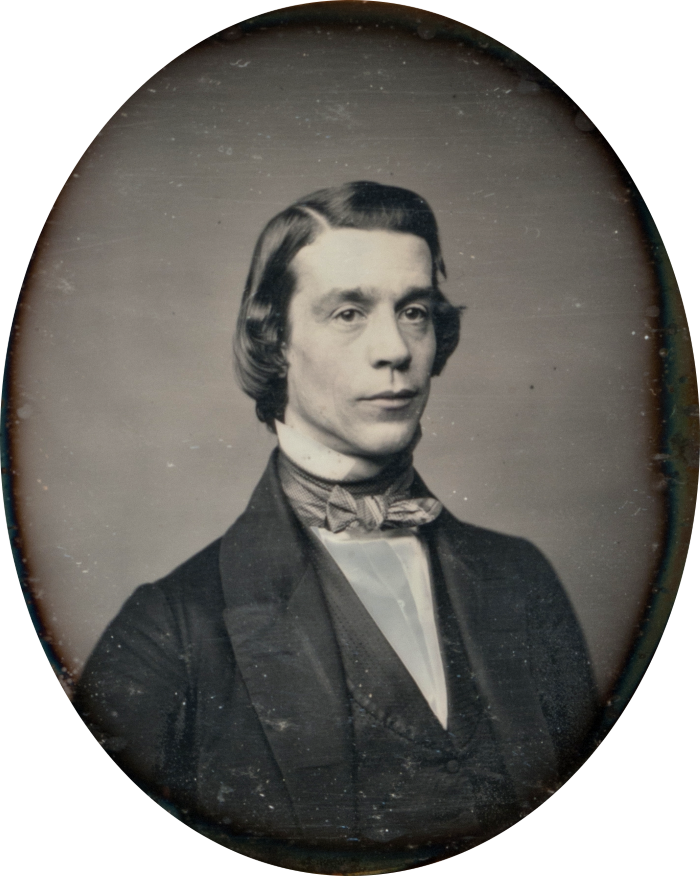

Thomas Starr King, c. 1855

Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org, Public Domain image.

Anyone who has driven east on Geary Boulevard from the Richmond District knows that, as you pass Gough, the road bends to the south and then east again to connect with O’Farrell. Not everyone knows that this one block crossover is called Starr King Way. Though perhaps not so well known today, the name honors one of the most influential men in early California history, Thomas Starr King, often just called Starr King.

Starr King was born in New York City in 1824, the song of a Universalist minister. He became a minister himself and took over his father’s then church in Charlestown, Massachusetts at the age of 20. During a stint at another Universalist church in Boston, Starr King became one of the most famous preachers in America. He joined the lyceum circuit, where famous speakers, such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, would talk to large crowds to educate them about the important issues of the day, and become one of the most popular speakers.

Thomas Starr King's sarcophagus at Geary and Franklin, c. 1900.

Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org, wnp27.3034

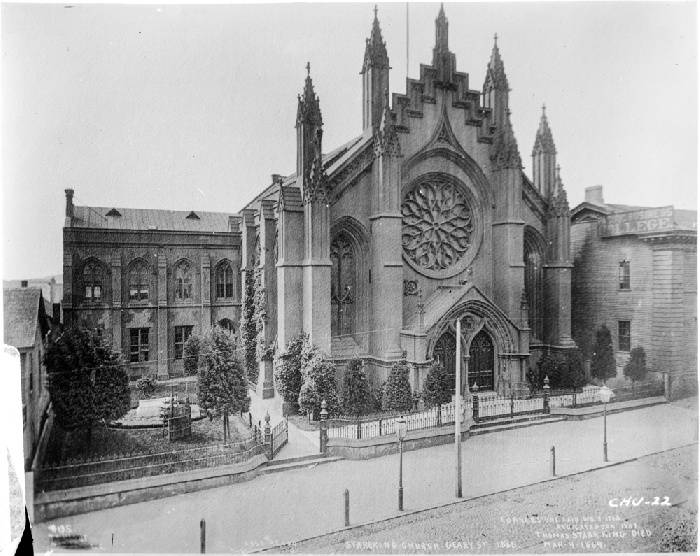

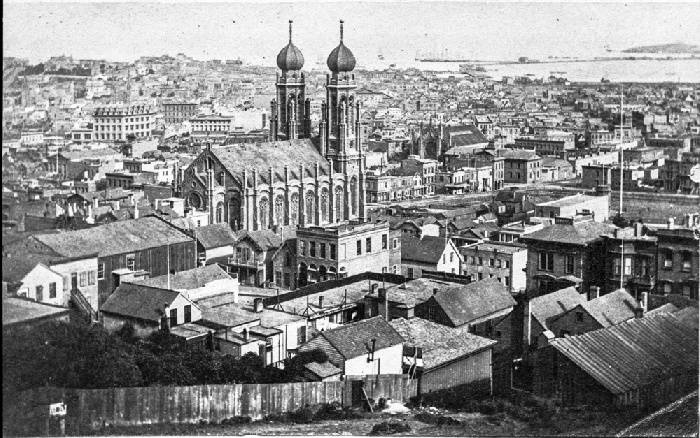

In 1860, Starr King agreed to come west to the First Unitarian Church in San Francisco, one of many locations that sought his ministerial services. Starr King believed he could be of more use in California as there were many Unitarian ministers in the Northeast at that time. First Unitarian was then located at 805 Stockton Street near Sacramento Street and was deep in debt. Starr King quickly raised enough money to pay off the debt and then began fundraising for a bigger facility. A new First Unitarian Church at 133 Geary Street near Stockton would be completed by January 1864.

Soon after Starr King arrived in San Francisco, he visited Yosemite. The experience was a moving one for him and, upon his return, he began advocating, in sermons and published letters, for Yosemite to be preserved. His campaign and the support of other prominent citizens would eventually lead to Congress passing a bill, signed by President Lincoln in 1864, to preserve Yosemite, the first time the United States set aside federal lands for use as a park for public use.

On August 1, 1860, Starr King gave a speech at a celebration for free black people. In his speech, he declared that the divine mission of the church was to “proclaim equality of the races.(1)”

First Unitarian Universalist Church on Geary near Stockton c 1865.

Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org, wnp71.0078.jpg

View southeast across Union Square, Temple Emanu-el in foreground and First Unitarian Church to the right and behind, circa 1867.

Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org, wnp37.0067.jpg

A year after Starr King’s arrival in San Francisco, the Civil War broke out. Starr King was a dedicated abolitionist and gave many passionate speeches around the state in favor of the Union. Abraham Lincoln allegedly credited Starr King with keeping California in the Union. Starr King also accompanied and spoke on behalf of his friend Leland Stanford, as he stumped around the state in 1861 as part of Stanford’s successful campaign to become governor. After California was safely on the side of the Union in the Civil War, Starr King began raising money and medical supplies for wounded soldiers through the Pacific Branch of the United States Sanitary Commission. Starr King’s efforts were extremely successful, raising more than $1.5 million dollars, an extraordinary amount at the time.

Starr King’s penchant for frequently giving speeches may have been his downfall. A small, frail man, his frequent trips around the state to give speeches resulted in exhaustion. In 1864, his exhaustion led to diphtheria and pneumonia. As Starr King lay dying, he dictated his will and told his wife that he saw the “privileges and greatness of the future.” On March 4, 1864, Starr King passed away. 20,000 people attended his funeral, flags around the City were flown at half-mast, and his friend, the author Bret Harte gave a moving eulogy. Starr King was entombed in a sarcophagus on the grounds of First Unitarian Church. He was just 39 years old at his death.

In 1889, the First Unitarian Church moved to its present location at 1187 Franklin Street at Geary. Starr King’s sarcophagus moved with the church to its new location. The new church suffered some damage in the 1906 earthquake, but fortunately, the new location was just outside of the fire zone. The bell tower and steeple you see in the image above were damaged resulting in their removal. The First Unitarian Church is now San Francisco Landmark #40.

In addition to the one block street named after him, Starr King has been memorialized in many ways. There is a mountain peak in Yosemite and a giant sequoia in Calaveras Big Trees State Park named for him. Several churches and a number of schools also carry his name, including Starr King Elementary School in the Potrero Hill neighborhood. That school is next to the Starr King Open Space Park. Starr King was considered such a vital piece of California history that he was voted one of the State’s two greatest heroes (along with Junipero Serra) to be added in statuary form in the National Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C.

In San Francisco, a statue of Starr King, sculpted by Daniel Chester French, was erected in Golden Gate Park. It was dedicated on October 26, 1892. A crowd of 2000 attended the dedication, including Starr King’s grandsons.2 The Park Band played the Coronation Grand March. J.B. Stetson of the California Street Cable Car Company told the crowd that “[t]here were none among the stanch friends of the Union who did more to save it with loyal and eloquent words than Thomas Starr King.” The patriotism of Starr King was a theme of several speakers. To learn a little more about Starr King statue in Golden Gate Park, listen to our Outside Lands Podcast on the Starr King Monument.

As this years elapsed, the memory of Starr King faded. When State Senator Dennis Hollingsworth sponsored legislation in 2006 to replace the Starr King statue in the National Statuary Hall with one of Ronald Reagan, he admitted that he did not know who Starr King was.(3) Although removed from D.C., the statue was relocated to the California State Museum and Park in Sacramento. Starr King also still remains at the First Unitarian Church today. Unlike most other gravesites in San Francisco that were removed from the City, his sarcophagus can still be found at the church in the corner of its lot near O’Farrell Street. His name may not be well-known now, but he will always be one of the great men of early San Francisco history.

Thomas Starr King gravesite at Franklin and Geary, 2018.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Historic plaque on site.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Notes:

1. “Looking Back – Starr King,” Richmond Review/Sunset Beacon, July 4, 2020. https://sfrichmondreview.com/2020/07/04/looking-back-starr-king/

2. “Thomas Starr King, Unveiling of His Memorial Statue,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 27, 1892, p. 8.

3. “Debate urged on Starr King eviction,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 25, 2006, p. B3.