CELLspace: 1996-2012: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' ''By Russell Howze, with Jonathan Youtt and Devin Holt'' CELLspace wa...") |

(added link) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

''By Russell Howze, with Jonathan Youtt and Devin Holt'' | ''By Russell Howze, with Jonathan Youtt and Devin Holt'' | ||

CELLspace was founded on the Spring Equinox of 1996 when a group of artists and educators leased a former screen-printing warehouse — a 10,000 square foot bay in a larger building that had three more bays of industrial and arts businesses — at 2050 Bryant Street to develop a communal workspace for collaborative and community-based arts. Jonathan Youtt, Justin Bondi and Tryntje Rapalje were living in a dusty, illegal unit attached above the warehouse at 2048 Bryant Street, in what was then called the North East Mission Industrial Zone. It was a vibrant scene, with live music, puppet shows and independent film nights. The unit also had a tiny window in their bathroom that looked out into the screen-printing shop. In the quieter moments, they would gaze out the bathroom window and watch the T-shirts dry. They would imagine a better world. A world with art. A world with community. | [[Image:CELLspace-bboy-and-bgirl-jam-c.jpg]] | ||

'''CELLspace bboy and bgirl jam, a regular event for many of the years CELLspace existed.''' | |||

''Photo: Russell Howze'' | |||

[[CELLspace|CELLspace]] was founded on the Spring Equinox of 1996 when a group of artists and educators leased a former screen-printing warehouse — a 10,000 square foot bay in a larger building that had three more bays of industrial and arts businesses — at 2050 Bryant Street to develop a communal workspace for collaborative and community-based arts. Jonathan Youtt, Justin Bondi and Tryntje Rapalje were living in a dusty, illegal unit attached above the warehouse at 2048 Bryant Street, in what was then called the North East Mission Industrial Zone. It was a vibrant scene, with live music, puppet shows and independent film nights. The unit also had a tiny window in their bathroom that looked out into the screen-printing shop. In the quieter moments, they would gaze out the bathroom window and watch the T-shirts dry. They would imagine a better world. A world with art. A world with community. | |||

One morning, the window showed the business moving out down in the warehouse. At a time when you could still find a room in the Mission for $300 a month, and the Dotcom Boom hadn’t turned empty warehouses into prime real estate, the artists soon signed a lease with landlord Barnie Klein. They quickly recognized Klein as the group’s “first supporter” since he allowed rag-tag artists with big ideas and almost no financial resources to rent a huge warehouse with no credit check. | One morning, the window showed the business moving out down in the warehouse. At a time when you could still find a room in the Mission for $300 a month, and the Dotcom Boom hadn’t turned empty warehouses into prime real estate, the artists soon signed a lease with landlord Barnie Klein. They quickly recognized Klein as the group’s “first supporter” since he allowed rag-tag artists with big ideas and almost no financial resources to rent a huge warehouse with no credit check. | ||

| Line 18: | Line 24: | ||

Burning Man’s Associate Director of Community Events Steven Raspa held his first interactive art exhibit in that gallery. “Cell has played a vital and significant role in the underground creative community in the Bay Area for many years,” he said, adding that he could recall, “numerous mad-capped happenings that defied explanation.” | Burning Man’s Associate Director of Community Events Steven Raspa held his first interactive art exhibit in that gallery. “Cell has played a vital and significant role in the underground creative community in the Bay Area for many years,” he said, adding that he could recall, “numerous mad-capped happenings that defied explanation.” | ||

[[Image:CELLspace-with-event-c.jpg]] | |||

'''Big event at CELLspace, the financial mainstay of the space.''' | |||

''Photo: Russell Howze'' | |||

Most people who went there, went to those mad-capped happenings: all-night dance parties that began with a yoga lesson and ended with the Extra Action Marching Band, literary events with David Byrne, beats from Bassnectar when he was DJ Lorin, breakdancing competitions, mechanical bull riding, hip hop theater, live chainsaw massacres, puppet circus suppers, blindfolded transcendental meditation workshops, and youth hip hop nights where gang members from the Nortenos, Surenos, Westmob and Big Block all danced together. | Most people who went there, went to those mad-capped happenings: all-night dance parties that began with a yoga lesson and ended with the Extra Action Marching Band, literary events with David Byrne, beats from Bassnectar when he was DJ Lorin, breakdancing competitions, mechanical bull riding, hip hop theater, live chainsaw massacres, puppet circus suppers, blindfolded transcendental meditation workshops, and youth hip hop nights where gang members from the Nortenos, Surenos, Westmob and Big Block all danced together. | ||

| Line 24: | Line 36: | ||

Managing these “clusters” were initially pulled off by 100% volunteer time, creativity and labor. By 2000, there were only three paid employees, called The Office Troika, that kept the office and administrative duties locked down. Even when the doors had to be locked for lack of people to keep the space open, volunteering was encouraged, and work trade was possible during the off hours at the space. | Managing these “clusters” were initially pulled off by 100% volunteer time, creativity and labor. By 2000, there were only three paid employees, called The Office Troika, that kept the office and administrative duties locked down. Even when the doors had to be locked for lack of people to keep the space open, volunteering was encouraged, and work trade was possible during the off hours at the space. | ||

[[Image:Cell-Space-DSC00097.jpg]] | |||

'''The ever-evolving facade of the space along Bryant Street.''' | |||

''Photo: Russell Howze'' | |||

Before the Troika, no one was getting paid to work at the Cell, and the folks living in the 2048 apartment began to call themselves Caretakers. Much of the energy in the space was driven by the 2048 Caretakers, and not all of it was positive. The caretaker system — where members traded “20 hours” of work in exchange for cheap rent upstairs — led to burnout, and monetary theft. Along with the regular volunteers (“Anyone can be a member of CELLspace… if they put the time in!” was a frequent saying in the space. “Safety Third” and “Safety Break” — time to smoke pot — were just as popular), the space was run by collective consensus, which involved painfully long meetings. One irate member could freeze decision making, and some meetings ended in screaming matches and tears. The Crucible’s Sturtz had heard the CELLspace horror stories, so decided not to allow his new organization to be collectively-run. While at times dysfunctional, CELLspace continued to grow and help anyone with an idea make it happen in the space. | Before the Troika, no one was getting paid to work at the Cell, and the folks living in the 2048 apartment began to call themselves Caretakers. Much of the energy in the space was driven by the 2048 Caretakers, and not all of it was positive. The caretaker system — where members traded “20 hours” of work in exchange for cheap rent upstairs — led to burnout, and monetary theft. Along with the regular volunteers (“Anyone can be a member of CELLspace… if they put the time in!” was a frequent saying in the space. “Safety Third” and “Safety Break” — time to smoke pot — were just as popular), the space was run by collective consensus, which involved painfully long meetings. One irate member could freeze decision making, and some meetings ended in screaming matches and tears. The Crucible’s Sturtz had heard the CELLspace horror stories, so decided not to allow his new organization to be collectively-run. While at times dysfunctional, CELLspace continued to grow and help anyone with an idea make it happen in the space. | ||

| Line 70: | Line 88: | ||

Mission Urban Arts — a Cell-founded after school program — used the extra building to teach breakdancing, DJing, and other skills to Mission youth. Bike-education group The Bike Kitchen taught their first free workshops at the Mission Village Market. Graffiti and Street Art also thrived at the Mission Village Market, as did studio rentals for video and sound media. As the Mission Village Market thrived, the lot was slated to get developed into mixed-income housing. | Mission Urban Arts — a Cell-founded after school program — used the extra building to teach breakdancing, DJing, and other skills to Mission youth. Bike-education group The Bike Kitchen taught their first free workshops at the Mission Village Market. Graffiti and Street Art also thrived at the Mission Village Market, as did studio rentals for video and sound media. As the Mission Village Market thrived, the lot was slated to get developed into mixed-income housing. | ||

[[Image:2002c-CELLspace-Birthday-04.jpg]] | |||

'''CELLspace birthday party, c. 2002.''' | |||

''Photo: Russell Howze'' | |||

Financial issues grew heavy. With the Main Space at 2050 Bryant shut down, the collective only allowed events for up to 49 people (CELL’s record attendance was most likely over 600 when people packed it in for a rave held by the Santa Cruz Raindance crew). The bills were being paid by the money raised with the flea market in the square block asphalt lot back on Florida Street, and the end was near as the lot headed towards development. | Financial issues grew heavy. With the Main Space at 2050 Bryant shut down, the collective only allowed events for up to 49 people (CELL’s record attendance was most likely over 600 when people packed it in for a rave held by the Santa Cruz Raindance crew). The bills were being paid by the money raised with the flea market in the square block asphalt lot back on Florida Street, and the end was near as the lot headed towards development. | ||

Latest revision as of 10:46, 14 July 2020

Historical Essay

By Russell Howze, with Jonathan Youtt and Devin Holt

CELLspace bboy and bgirl jam, a regular event for many of the years CELLspace existed.

Photo: Russell Howze

CELLspace was founded on the Spring Equinox of 1996 when a group of artists and educators leased a former screen-printing warehouse — a 10,000 square foot bay in a larger building that had three more bays of industrial and arts businesses — at 2050 Bryant Street to develop a communal workspace for collaborative and community-based arts. Jonathan Youtt, Justin Bondi and Tryntje Rapalje were living in a dusty, illegal unit attached above the warehouse at 2048 Bryant Street, in what was then called the North East Mission Industrial Zone. It was a vibrant scene, with live music, puppet shows and independent film nights. The unit also had a tiny window in their bathroom that looked out into the screen-printing shop. In the quieter moments, they would gaze out the bathroom window and watch the T-shirts dry. They would imagine a better world. A world with art. A world with community.

One morning, the window showed the business moving out down in the warehouse. At a time when you could still find a room in the Mission for $300 a month, and the Dotcom Boom hadn’t turned empty warehouses into prime real estate, the artists soon signed a lease with landlord Barnie Klein. They quickly recognized Klein as the group’s “first supporter” since he allowed rag-tag artists with big ideas and almost no financial resources to rent a huge warehouse with no credit check.

The 2048 group became a collective and named the space C.E.L.L. (Collectively Explorative Learning Labs). People instantly began calling the space Cell, the Cell, or simply 2050 Bryant. A bit later, the collective settled with naming the warehouse CELLspace, run by the Cell collective. The early years at Cell were marked by chaos and construction. With limited resources and no permits, the collective set out with the almost impossible task of manifesting the vision of creating a cooperative community art space while embracing the values of Playfulness, Sustainability, Art, Creativity, Collectivity, Respect, Education and Diversity. Many people pitched in their blood, sweat, and tears to manifest this shared vision.

Unpermitted events were held with minimal promotions, only giving out the address as the venue. These larger events paid the rent and allowed other activities to flourish. While the buildouts and events happened, Dave X was known to test his flamethrowers behind the building on Florida Street, Jojo La Plume created an open craft loft in the homemade mezzanine, and the Sisterz of the Underground offered free breakdancing lessons for aspiring b-girls on the main space floor. On some days, you might have seen all three happening at the same time.

During its first five years, there was no better place to see the Mission District’s artistic, multicultural vibe than the CELLspace. San Francisco prankster Chicken John was known to decorate the warehouse as a Las Vegas casino; the Flaming Lotus Girls created their first large scale fire installations in the CELLspace metal shop, and during Carnaval, the space would burst at the seams from the ritual drumming, colorful rattling costumes and sheer number of teenagers involved in groups like Loco Bloco and Danza Azteca.

Michael Sturtz was so impressed by CELLspace that in 1999 he named his industrial arts school, The Crucible, after their art gallery.

“The name was inspired by the Crucible Steel Gallery, which was the CELLspace gallery at the time,” he said.

Burning Man’s Associate Director of Community Events Steven Raspa held his first interactive art exhibit in that gallery. “Cell has played a vital and significant role in the underground creative community in the Bay Area for many years,” he said, adding that he could recall, “numerous mad-capped happenings that defied explanation.”

Big event at CELLspace, the financial mainstay of the space.

Photo: Russell Howze

Most people who went there, went to those mad-capped happenings: all-night dance parties that began with a yoga lesson and ended with the Extra Action Marching Band, literary events with David Byrne, beats from Bassnectar when he was DJ Lorin, breakdancing competitions, mechanical bull riding, hip hop theater, live chainsaw massacres, puppet circus suppers, blindfolded transcendental meditation workshops, and youth hip hop nights where gang members from the Nortenos, Surenos, Westmob and Big Block all danced together.

There were also classes, art shows, benefits, and smaller events that added to the breadth of culture developing at CELLspace. A regular bboy and bgirl jam started soon after the arts space opened, and became the longest running class/event/collaboration in the space. An arts gallery developed, as did a woodshop and metal welding shop. Studios began to be built out and rented.

Managing these “clusters” were initially pulled off by 100% volunteer time, creativity and labor. By 2000, there were only three paid employees, called The Office Troika, that kept the office and administrative duties locked down. Even when the doors had to be locked for lack of people to keep the space open, volunteering was encouraged, and work trade was possible during the off hours at the space.

The ever-evolving facade of the space along Bryant Street.

Photo: Russell Howze

Before the Troika, no one was getting paid to work at the Cell, and the folks living in the 2048 apartment began to call themselves Caretakers. Much of the energy in the space was driven by the 2048 Caretakers, and not all of it was positive. The caretaker system — where members traded “20 hours” of work in exchange for cheap rent upstairs — led to burnout, and monetary theft. Along with the regular volunteers (“Anyone can be a member of CELLspace… if they put the time in!” was a frequent saying in the space. “Safety Third” and “Safety Break” — time to smoke pot — were just as popular), the space was run by collective consensus, which involved painfully long meetings. One irate member could freeze decision making, and some meetings ended in screaming matches and tears. The Crucible’s Sturtz had heard the CELLspace horror stories, so decided not to allow his new organization to be collectively-run. While at times dysfunctional, CELLspace continued to grow and help anyone with an idea make it happen in the space.

Much of this healthy energy was genuine DIY. After Jonathan Youtt discovered local youth spray painting the exterior walls of the warehouse, he encouraged them to bring their culture inside the building. A young neighbor organized the first graffiti art mural exhibition as part of his Indigenous Peoples Day Celebration in 1996. It was the first of many youth oriented shows, teach-ins, political organizing events, and cultural expressions undertaken in conjunction with the conscious youth organizations that began to work with CELLspace: Olin, Homey, United Playaz, Brown Enterprises, Loco Bloco, and the Third Eye Movement to name a few. These orgs strategically organized to bring youth together and curb racial and gang violence through cultural intervention.

“We were the only community space for a while that would even touch youth [programming], and youth hip hop shows,” Youtt said. “We provided a place for the Third Eye Movement, United Playaz, and other groups to organize against Prop 21,” a 2000 ballot initiative that made it easier to try juveniles as adults. These organizations kept renting the space for rehearsal, benefits and shows, sometimes launching long-lasting projects from their initial events at CELLspace.

After that early mural project, Cell’s outside walls also stayed painted, serving as a long-running graffiti spot and eventually an early legal spot for street art styles (stencils, stickers, wheatpastes/posters) and murals. When the warehouse finally came down much later the walls had hosted artists such as Jet Martinez, SPIE, TIE, Swoon, Icy and Sot, Jeff Aerosol, Regan Ha-Ha Tamanui, Joker, CUBA, Adam Feibelman, Jesus Barraza, Melanie Cervantes, Claude Moller, Josh MacPhee, AmandaLynn, Cy Wagoner, and Joel Bergner. Joel Bergner painted his first outdoor mural, “De Frontera a Frontera,” on 2050 Bryant, for which he won Best Public Mural from Precita Eyes in 2004.

Around 2000, new ideas and energy kept coming into CELLspace’s doors. A dedicated staff of volunteers had nurtured and developed their vision over the years, and eventually filed for 501c3 (non-profit) status. The new digital arts volunteers began the CELLtv cable access show and put a cellspace.org website up on the booming word wide web. One of the only free computer lounges in San Francisco was set up for public use.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/9XHnxzE67BA" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

CELLtv Episode 1

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/_e9j8Mi3JPY" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

'CELLtv Episode 2

Large events kept paying the bills, allowing many free, pay what you can, and no one turned away (NOTA) events to happen. Circus arts began to book the space since it was easy to rig aerial equipment in the main space’s rafters. Roller skating and skateboarding groups transformed the large Main Space into a wheeled paradise in an era where skateboarding was an outlaw sport.

The art gallery took their name from the World War II era business that existed in the multibay warehouse: The Crucible Steel Gallery. The Crucible Steel Gallery didn’t take any cut in arts sales, spending more time inspiring and incubating artists with group shows than worrying about renting space or making profits. They would book shows three-months in advance and have to turn away artists who wanted to show at the gallery.

As the space became a solid partner and ally in the arts and activist communities, the Dot Com Boom began to affect many of the projects, programs, and ideas that were flowing through the space and organization. As the local pushback intensified, the space was opened up for local organizing against gentrification, and shows were created and hosted on the themes of displacement. CELLspace became a location for “Mission Movie”, a bilingual film touching on themes of gentrification and community, which also had Cell co-founder Jonathan Youtt in a few scenes.

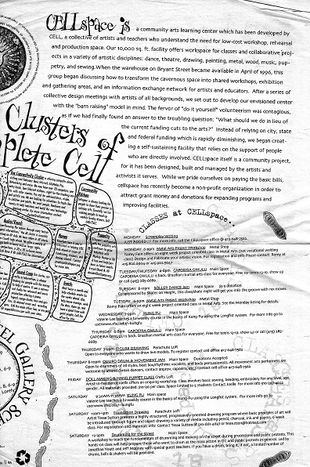

In response to the new and disturbing digital paradigm, including the “live work” condos that were getting built in the Mission, several CELL collective members decided to create a DIY newsletter to distribute and hand out in the Mission District. “The Blurb ran for a few issues, highlighting what was going on within the space. Putting the nonprofit mission and all the many ways to get involved on tabloid paper with printed ink was a bit of a defiant push back at the mad rush to get online and connected through computers.

Cellspace Blurb, a basic informational tabloid published in March 2000.

In any of a number of their regular newsletters, CELLspace always emphasized their strong connections to the community, and highlighted how easy it was to connect with the space.

Courtesy Jonathan Youtt

With growing notice and influence, the San Francisco Police Department started showing up and shutting down events at CELLspace. The building and fire inspectors showed up soon after, and began to enforce safety issues in the warehouse. With a little bit of grants funding thanks to the nonprofit’s grant-writing committee, and the development of professionally-run permitted building projects, some progress was made in getting the warehouse up to code. Events programming was eventually shut down while the collective scrambled to get a Place of Entertainment permit. The energy and loss of events profits was a huge blow to the collective.

In the midst of the wave of international protest post-Seattle WTO, the Dot Com Boom and Bust, and the NYC World Trade Center attacks, CELL pivoted in 2003 and took over the vacated truck rental lot and warehouse behind CELLspace on Florida Street. The collective turned the new space into the Mission Village Market. After squatters had set fire to the back lot’s warehouse, Jonathan Youtt convinced the owner to let Cell have fundraisers there. The Mission Village Market grew to be Cell’s biggest moneymaker, and rivaled the Alemany Flea Market as a destination for vendors.

Mission Urban Arts — a Cell-founded after school program — used the extra building to teach breakdancing, DJing, and other skills to Mission youth. Bike-education group The Bike Kitchen taught their first free workshops at the Mission Village Market. Graffiti and Street Art also thrived at the Mission Village Market, as did studio rentals for video and sound media. As the Mission Village Market thrived, the lot was slated to get developed into mixed-income housing.

CELLspace birthday party, c. 2002.

Photo: Russell Howze

Financial issues grew heavy. With the Main Space at 2050 Bryant shut down, the collective only allowed events for up to 49 people (CELL’s record attendance was most likely over 600 when people packed it in for a rave held by the Santa Cruz Raindance crew). The bills were being paid by the money raised with the flea market in the square block asphalt lot back on Florida Street, and the end was near as the lot headed towards development.

Continuing to pivot, CELLspace grew in its scope and outreach, expanding into more youth services that offered after school arts classes, tutoring, counseling, off-site workshops, leadership opportunities, and vocational training. A three year capital campaign helped a city-mandated renovation project needed to obtain our Place of Entertainment permit in 2005. As Cell grew up, the culture changed.

The space relied less on volunteers, artists and live-in caretakers, and more on paid staff. Collective consensus gave way to weekly staff meetings, and monthly board meetings, as nonprofit status required by law. During this transition, most of the original members left.

“In the '90s it was, live there for nothing, work your ass off,” said Russell Howze, a longtime CELLspace member. But by the time Howze quit volunteering in 2005 he said, “the culture of making art for participation’s sake was pretty much gone.”

CELLspace’s notoriety peaked, but the financial difficulties didn’t stop. Cell’s tenth birthday party in 2006 was attended by a who’s who of Mission nonprofit workers, and politicians like Tom Ammiano and Chris Daly. But later that year, CELLspace lost the Mission Village Market, and had to move all of it’s programs into one building, and the needs of the competing programs clashed.

Tension grew between the events department and the staff who ran the youth program, leading to subtle accusations of racism on both sides. The dream of becoming an above ground event space was ignored as the managers and employees continued to focus on its growing, and funded, youth support and services. As artists began to migrate out of the Mission District and San Francisco, the CELL studios were converted to offices.

Grants helped to cover the loss of income from the market, but a lot of the money was wasted. After one of the larger grants was received, the staff were given cell phones for conducting CELLspace business. Within one year, they would have no business to conduct. The bills got ahead of the funding, and the nonprofit began a free-fall into debt and unpaid bills.

“Essentially, large amounts of money were mismanaged, one grant in particular from DCYF (Department of Children Youth and Families). Money was spent on things it shouldn’t have been, there were gang dynamics in place — it became a high risk situation in some of the decisions that were made, programmatically and financially,” said one former employee who preferred to remain anonymous.

In 2007, paychecks for employees of Def-Ed, the Adult Art Education Program and Mission Urban Arts started bouncing. After months of assurances, waiting, and mystery from management, everyone was laid off. Classes were cancelled, events business fell off, and a locked door at 2050 Bryant St. became the norm. Distraught by the upheaval, former employees Helen McGrath, Lizbett Calleros, and former Board President Dorian Johnson reached out to older members and formed a small coalition of volunteers to save CELLspace.

Headed by Johnson and Dave X, a group of the early collective members came back to try to help the remaining Cell folks steer the CELLspace ship back on the proper course.

“Dave X and Dorian Johnson really gave it a go,” said Howze, who also came back to volunteer after the crash.

But in 2009, the fire department told CELLspace that even though they had a Place of Entertainment permit, they would now need a separate Place of Assembly permit. That meant construction, and Cell didn’t have the money, or the volunteer base, to get it done.

As financial burdens grew, several businesses and organizations also stepped up to support the organization. Artists came back to rent the studios and the 2048 Loft was remodeled into an artist in residency program. The Crucible Steel Gallery found new energized organizers and became SpaceCraft. The bboys and bgirls continued to jam, and there was a wildly successful tango night that consistently filled the main space one night a week. The Church of 8 Wheels packed the house for roller skating benefits. Vau de Vire, a well-funded circus troupe, began to rent space to develop and rehearse shows.

But the pain continued. The police and inspectors kept showing up, the plan to build out a legal event space couldn’t get a self-contained fire exit project totally funded, and the debt from the now-dissolved nonprofit could not be overcome. The scars of the first tech boom, and the beginnings of another one, cut the interest in generating a new and younger volunteer base to fill all the laborious needs for a sustainable version of Cell. This lack of interest, combined with the ongoing financial difficulties and the impact of the Great Recession, forced CELLspace to dissolve as an organization in 2012.

Dave X felt that the space could, and would have survived, if more people had pulled together to finish the final construction project for the POA — an enclosed exit in the back.

“In the end it went down not because it was getting shut down by the cops or whatever, but it closed because of our own incompetence,” he said.

2050 Bryant was still leased to CELLspace until December 31st, 2012. As the lease renewal came due, Vau de Vire took over the space and renamed it Inner Mission. They continued to support the exterior wall mural projects, the many classes and rehearsals that booked the space, SpaceCraft, and the remaining rented studios. The vision was to turn Inner Mission into a totally funded and permitted above ground space.

Russell Howze and Jonathan Youtt saw the transfer of CELLspace from a non-profit community center to a for profit entertainment business, as another symbol of the Mission district’s gentrification, and the decline of the arts culture in San Francisco.

“In the long run, the spirit had moved to Oakland,” Youtt said.

After the final demise of CELLspace as a nonprofit, group, and space, Inner Mission had successful lease negotiations with now-owner Lloyd Klein. They were about to sign the lease and invest a huge amount of money to finally legalize the space, when Klein ended negotiations. Before they could sign a new lease Klein announced that he had sold his whole four-bay building to local developer Nick Podell.

As Podell began to submit plans for his new building, neighbors and artists began to wake up to the new Tech Boom. Huge condo developments began to get approved across San Francisco, especially in the western neighborhoods like the Mission, and fierce pushback by communities soon followed. Podell’s plan to tear down the old warehouse and build a majority market rate development with boutique retail was dubbed “The Beast on Bryant” by neighbors, artists and activists. A group of artists began to squat the 2048 apartment mostly to cause legal problems for the new owner.

Vau de Vire was hit hard by the backroom deal between the landlord and developer, and, like many artists and arts groups, left San Francisco for the East Bay.

The local resistance to the Beast on Bryant was effective. Podell revised his original plans, and he eventually donated 33% of the block to the city's affordable housing department to avoid having to build affordable units in their luxury housing development. Later, MEDA (Mission Economic Development Agency), a local nonprofit developer, won the contract from the City to build mixed-income dwellings with a CELLspace-inspired 10,000 square foot community arts space. The rest of the block was slated for market-rate condos.

In late 2017, the warehouse that held CELLspace, the A.C.T. prop shop, Barnie Klein’s machine shop, and an automobile mechanic shop was torn down. A few other small businesses and private residences in the remaining buildings on the block were also torn down. As of this writing, the mixed-income housing on the corner of 18th and Bryant is nearing completion.

New apartment building nearing completion at Bryant and Mariposa on the old site of Cellspace, 2020.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

CELLspace’s inspiration, drive, and DIY ethic lives on! The Crucible, American Steel, SPACE, The Box Shop, and many other spaces are directly influenced by the CELLspace. The ideals also live on in artist's projects and hearts and minds of the thousands who created and spectated at the warehouse space. CELL provided affordable space for artists to work on many types of media, including events and exhibits, puppetry, circus arts, welding, machine arts, fine arts, performing arts, craft making, digital arts, graffiti and street art, and music recording.

The myriad troupes, groups, crews, and posses that grew out of this space went on to inspire culture and future art spaces around the world. Let this remind us of the power of an idea whose time has come....