Architectural Mission: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(added links) |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

'''Great diversity of styles''' | '''Great diversity of styles''' | ||

The diversity of Mission District building types and styles is great: characteristic flat-roofed Victorian, stick-style houses, and ornately gabled Queen | The diversity of Mission District building types and styles is great: [[Shotwell Architectural Tour|characteristic flat-roofed Victorian, stick-style houses, and ornately gabled Queen Annes]]—sometimes speculatively built in cookie-cutter rows. Italianate or Mission Revival mixed-use (commercial-residential) apartment buildings. Stripped-down functional or deco-detailed industrial warehouses. Grander residential dwellings along Dolores Street and [[More Mission Architecture|Fair Oaks]]. And the faded grandeur of Folsom, with its graceful fringe of Chinese Elms. | ||

[[Image:Folsom-street-trees 9141.jpg]] | [[Image:Folsom-street-trees 9141.jpg]] | ||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

Cultural diversity, over time, generates a particular kind of visual dynamism, which, in turn, attracts diverse residents and visitors, drawn subliminally and consciously. Plane trees recall sycamores that grew in "the Old Country." Iron-fenced front rose gardens replay English and Irish ones. Atop a narrow street, a transept window's Star of David echoes an older Jewish community. The angle of a church spire resonates in memory. | Cultural diversity, over time, generates a particular kind of visual dynamism, which, in turn, attracts diverse residents and visitors, drawn subliminally and consciously. Plane trees recall sycamores that grew in "the Old Country." Iron-fenced front rose gardens replay English and Irish ones. Atop a narrow street, a transept window's Star of David echoes an older Jewish community. The angle of a church spire resonates in memory. | ||

To be sure, low rents are a least common denominator. Above Valencia Street's punk and grunge-chic, second-hand clothing, furniture and book stores, cheap railroad flats house minority families and collectives of young people and punk musicians. | To be sure, low rents are a least common denominator. Above [[Valencia Street, circa 1981, Bohemian Roots of Gentrification|Valencia Street's punk and grunge-chic, second-hand clothing, furniture and book stores]], cheap railroad flats house minority families and collectives of young people and punk musicians. | ||

Incremental development, over nearly 210 years, has produced a long period of significant building, too, in many architectural styles, says Andreini. The Mission District is not one but a half-dozen walking tours. There's the wonderful tour run by Precita Eyes Mural Center, that starts at Precita Park, runs down Harrison, jogs left to [[Balmy Alley: a Modernist Approach|Balmy Alley]] (a mural-lover's paradise), right along 24th Street, and ends at the children's pocket park near York Street. En route, 3-D buildings are backdrops—their personalities subsumed as 2-D canvases out of which original vistas unfold. | Incremental development, over nearly 210 years, has produced a long period of significant building, too, in many architectural styles, says Andreini. The Mission District is not one but a half-dozen walking tours. There's the wonderful tour run by Precita Eyes Mural Center, that starts at Precita Park, runs down Harrison, jogs left to [[Balmy Alley: a Modernist Approach|Balmy Alley]] (a mural-lover's paradise), right along 24th Street, and ends at the children's pocket park near York Street. En route, 3-D buildings are backdrops—their personalities subsumed as 2-D canvases out of which original vistas unfold. | ||

Latest revision as of 13:20, 14 June 2020

Historical Essay

by Diana Scott

The visual richness of the Mission District among San Francisco neighborhoods is the result of a long gestation period—over two centuries of building, rebuilding and recycling.

The house at 822 S. Van Ness Ave. In 1883 it was a wedding present from Claus Mangels to his daughter. The Sisters of the Holy Cross bought it in 1913 as a residence for teaching nuns and added a third story in 1921. They sold it sometime after 1959 and at one point it served as a residence for Native American boys.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The Mission has a foundation and overlay of Hispanic culture clearly visible in the original Mission Dolores from which it takes its name, in Mission Revival style buildings, in ubiquitous taquerias and panaderias, and in its vibrant mural tradition, more evident here than perhaps in any city in North America. Yet many other cultures are layered in its physical history. Italian, Irish, German, Jewish, Scandinavian and Asian, as well as Ohlone and Yankee, all have left their imprints.

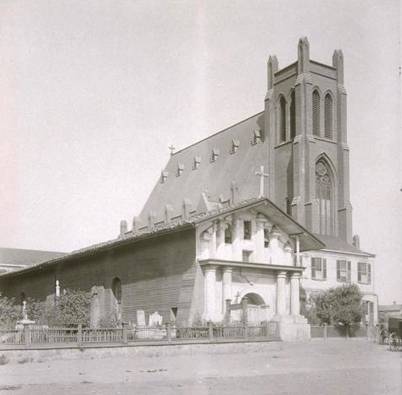

Mission Dolores, c. 1898

Photo: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley

The original Mission chapel of sun-dried adobe brick and whitewashed stucco at Dolores Street near 16th Street, survivor of several earthquakes, was the kernel; a path was beaten from the harbor to its door that later set the angle of Market Street.

Its establishment among the first permanent structures on a relatively sheltered plain, next to a meandering creek, was an act of faith and planning. It did not abut Dolores Park, which would await well over a century to be created.

Still, more than 5,000 Native Americans, who are to be commemorated by name and with a monument, were buried near the Mission, members of a Costanoan tribe that predated the Spanish.

And in the sunlit courtyard cemetery behind Mission Dolores, amid rose bushes and stone saints, names on tombstones from the 1850s surprisingly match birthplaces like Limerick County, Ireland.

Great diversity of styles

The diversity of Mission District building types and styles is great: characteristic flat-roofed Victorian, stick-style houses, and ornately gabled Queen Annes—sometimes speculatively built in cookie-cutter rows. Italianate or Mission Revival mixed-use (commercial-residential) apartment buildings. Stripped-down functional or deco-detailed industrial warehouses. Grander residential dwellings along Dolores Street and Fair Oaks. And the faded grandeur of Folsom, with its graceful fringe of Chinese Elms.

Chinese Elms along Folsom between 24th and 25th Streets, 2009.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

"(The district's) visual richness is quite remarkable," says Don Andreini, editor of the newsletter of the preservationist group Foundation for San Francisco's Architectural Heritage.

Changing commercial uses have kept many buildings alive. On the long commercial spine of Valencia, a Mission Revival-style auto shop, transformed from a stable, evolves into a Spanish church. Some industrial lofts and warehouses that grew up near the Bay and highways, east of Mission and north of Cesar Chavez, where the 1906 fire once raged, have become live-work studios for artists and writers, as industry moved elsewhere; others still house light industry.

Part of the Golden Gate Woolen Manufacturing Co., at 20th and York streets, built in the 1880's; it later was used to manufacture furniture, and today is mostly offices.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Color—and transparency—augment structural details. At Mission and 15th Street, a four-story stucco building that would be at home in Miami is awash with pale coral, overlaid with a large lattice of light turquoise trim. On Valencia Street near 17th, at the Community Thrift Store, recycled goods beckon behind rainbow-browed doors from what may have been another stable-cum-auto repair shop.

Nearby, on 18th Street, a former German gymnasium, now the Women's Building, is decked to its gables with a resplendent second skin—a supersized mural celebrating women's achievements. Further south, a trade school that became the Mission campus of City College sports glass-block silo stairwells, in the streamlined moderne style that prefigured architectural modernism.

Says Andreini of a day he spent recently taking photographs in the Mission, "It was one of the most exciting days I've spent visually, in terms of looking."

Mission borders

The Mission is roughly bounded by Dolores Street on the west, Potrero on the east, Cesar Chavez on the south and 14th on the north. Its commercial boulevards—Mission and Valencia streets, 24th and 16th streets—alternate with major traffic corridors—Guerrero, South Van Ness, Bryant, Chavez—and residential blocks.

Broad, tree- and residence-lined avenues like Dolores and Folsom streets speak softly of an earlier use of “boulevard," a place to see and be seen. Blessed both by walker-friendly flatness and fog-blocking peaks that let sun shine longer here, the district is fertile ground for a variety of trees.

Cultural diversity, over time, generates a particular kind of visual dynamism, which, in turn, attracts diverse residents and visitors, drawn subliminally and consciously. Plane trees recall sycamores that grew in "the Old Country." Iron-fenced front rose gardens replay English and Irish ones. Atop a narrow street, a transept window's Star of David echoes an older Jewish community. The angle of a church spire resonates in memory.

To be sure, low rents are a least common denominator. Above Valencia Street's punk and grunge-chic, second-hand clothing, furniture and book stores, cheap railroad flats house minority families and collectives of young people and punk musicians.

Incremental development, over nearly 210 years, has produced a long period of significant building, too, in many architectural styles, says Andreini. The Mission District is not one but a half-dozen walking tours. There's the wonderful tour run by Precita Eyes Mural Center, that starts at Precita Park, runs down Harrison, jogs left to Balmy Alley (a mural-lover's paradise), right along 24th Street, and ends at the children's pocket park near York Street. En route, 3-D buildings are backdrops—their personalities subsumed as 2-D canvases out of which original vistas unfold.

Mission Branch Library, corner of Bartlett and 24th Streets, 2009.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The landmark Mission Public Library on 24th Street, housed in a proud Beaux Arts building donated to the city by Andrew Carnegie, has a brochure of several, more traditional, Victorian walking tours.

Each with a story

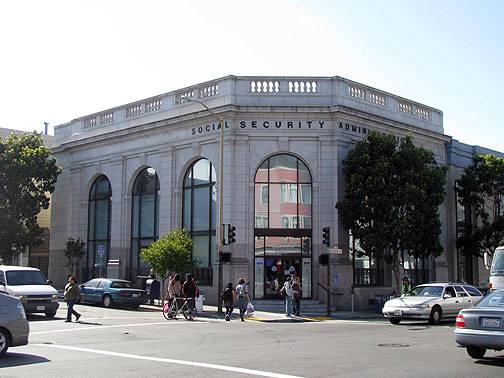

Former Hibernia Bank at 22nd and Valencia, now housing a Social Security Administration office, 2009.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

But each building also has its own story to tell, if you look closely: from the elegant gray stone eminence of the former Hibernia Bank at Valencia and 22rd streets, whose arching, plywood-lidded windows await a new tenant to open them; to the rounded brick-and-shingle turrets of Mission Presbyterian Church at Capp and 23rd streets; to the small, flat, mandala-punched facade of Pacto Evangelico up the street.

Mission Presbyterian Church, 23rd and Capp Streets, 2009.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Some buildings house original tenants; many have been "nipped and tucked" repeatedly to match needs of subsequent ones. Here and there, an ornamental bracket peaks out from behind a massive "modern" facelift of the '50s and '60s, or lovely lines assert themselves beneath asbestos brick.

Documenting the Mission's diverse structures is a goal of the Foundation for San Francisco's Architectural Heritage. "Splendid Survivors" resulted from its first survey, of downtown. Amassing information on individual buildings and architects will ensure, in part, that this heritage is accessible, not only to city residents but also to planners and prospective developers, who, in focusing on the bottom line, too often look no further than the lot line.

A Mission survey will likely result in another photo-illustrated volume of salient stylistic and historical examples—rare or excellent; culturally, contextually, and historically significant; generally beloved. In the past, while targeting certain portions of a district, professional staff have welcomed input from lay people, to supplement the architectural record.

Have you kissed a Mission building lately? Kodaked it, perchance? Or kicked a bulldozer?

Originally published in the San Francisco Examiner, Wednesday, September 13, 1995.