Chinatown's 19th Century Tourist Terrain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

''Photo: Bancroft Library, BANC-PIC-1985.084-125--ALB'' | ''Photo: Bancroft Library, BANC-PIC-1985.084-125--ALB'' | ||

[[Image:Chinatown hb7x0nb25d-FID4.jpg]] | |||

'''Street scene, 1890s.''' | |||

''Photo: Online Archive of California'' | |||

On May 18, 1886, a teenage girl identified only as E.G.H. arrived in San Francisco, one of many destinations on her trip through the West-perhaps with a Raymond Excursion Party—that had begun in Boston and included stops in Chicago, Kansas City, Santa Fe, Albuquerque, Los Angeles, Yosemite, and Mariposa. That day, from her "wonderful" accommodations at the city's luxurious Palace Hotel, she wrote to her "dear" Jay: "I am looking forward to my visit to Chinatown, where we are hoping to go in a day or two." Over the course of the next two weeks, E.G.H. made at least three trips into Chinatown, telling one recipient of her letters that she had "given as much time as possible to Chinatown" and was "fairly infatuated with the place."(l) | On May 18, 1886, a teenage girl identified only as E.G.H. arrived in San Francisco, one of many destinations on her trip through the West-perhaps with a Raymond Excursion Party—that had begun in Boston and included stops in Chicago, Kansas City, Santa Fe, Albuquerque, Los Angeles, Yosemite, and Mariposa. That day, from her "wonderful" accommodations at the city's luxurious Palace Hotel, she wrote to her "dear" Jay: "I am looking forward to my visit to Chinatown, where we are hoping to go in a day or two." Over the course of the next two weeks, E.G.H. made at least three trips into Chinatown, telling one recipient of her letters that she had "given as much time as possible to Chinatown" and was "fairly infatuated with the place."(l) | ||

| Line 56: | Line 62: | ||

Police guides, moreover, were known for deploying quite brutal, invasive, and generally disrespectful tactics that included kicking doors open, forcing their way into private living quarters, waking people from sleep, and shining bright lights into people's faces. Whether these encounters were staged or not, they made violence an expected part of the tourist experience in Chinatown. Local photographers capitalized on these expectations and sold souvenir photographs that claimed to "show the Chinaman taken by surprise, as the flash light illuminates his den." Photographer Henry R. Knapp packaged his series of such images in a three-inch square booklet, which made them easily portable and well suited for carrying in one's pocket or purse. The scenes he captured and captioned included the expected "Opium Den" and "Filling Opium Pipe," but the inclusion of "Old Blind Chinese Woman, Aged 77" and "Trimming His Corns" disclosed tourists' appetite for being let into private moments, not just vicious ones.(18) | Police guides, moreover, were known for deploying quite brutal, invasive, and generally disrespectful tactics that included kicking doors open, forcing their way into private living quarters, waking people from sleep, and shining bright lights into people's faces. Whether these encounters were staged or not, they made violence an expected part of the tourist experience in Chinatown. Local photographers capitalized on these expectations and sold souvenir photographs that claimed to "show the Chinaman taken by surprise, as the flash light illuminates his den." Photographer Henry R. Knapp packaged his series of such images in a three-inch square booklet, which made them easily portable and well suited for carrying in one's pocket or purse. The scenes he captured and captioned included the expected "Opium Den" and "Filling Opium Pipe," but the inclusion of "Old Blind Chinese Woman, Aged 77" and "Trimming His Corns" disclosed tourists' appetite for being let into private moments, not just vicious ones.(18) | ||

<br> | |||

[[Image:Opium-den-1.gif|300px|left]] [[Image:Filling-opium-pipe-2.gif|300px|right]] | [[Image:Opium-den-1.gif|300px|left]] [[Image:Filling-opium-pipe-2.gif|300px|right]] | ||

<br> | |||

'''These images were packaged with others in a three-inch-square book let designed to be easily portable, well suited for carrying in a pocket or purse. While "Opium Den" (top left) and "Filling Opium Pipe" (top right) presented expected tropes of the tourist terrain, "Old Blind Woman" (bottom left) and "Trimming His Corns" (bottom right) revealed the desire of tourists to view—and the power of the photographer to capture—ostensibly private, domestic scenes as well as vicious ones.''' | |||

''Photos: Henry R. Knapp, 1889. Huntington Library'' | |||

<br> | |||

[[Image:Old-blind-woman-3.gif|300px|left]] [[Image:Trimming-corns-4.gif|300px|right]] | [[Image:Old-blind-woman-3.gif|300px|left]] [[Image:Trimming-corns-4.gif|300px|right]] | ||

<br> | |||

Long-time San Franciscan Charles Warren Stoddard told a story of how when his "‘special,' by the authority vested in him" demanded admittance to a particular closed door, "a group of coolies" who lived in the vicinity and had followed the tourists tried to divert his attention by assuring him that the place was vacant. The officer refused to leave, decided to employ force to open the door, and when he did, succeeded in revealing four sleeping men, "packed" into what Stoddard described as an "air-tight compartment" and "insensible" to the "hearty greeting" the tourists offered. W H. Gleadell related invading the living quarters of an impoverished Chinese couple—upon his police guide's instruction—in order to be able to take in such a scene firsthand. The officer enticed him with the statement, "'Now, if you would really wish to see how some of the lower class of Chinese live, this is not a bad place for the purpose. Go down that stair, push open the door at the foot, and walk right in.'" Armed with his guide's permission and his own sense of entitlement, Gleadell persevered. He came upon a room in which he was "just able to stand upright" and "with the exception of a stove in one corner" and some straw matting that "answered the purpose of a bed" was otherwise "quite destitute of furniture." At "one end crouched a man, while a woman sat in the centre, and a wretched little cur groveled between them." Then, "after a general survey"—complete with commentary on the "loathsome squalor" of Chinatown that was so typical of the tourist literature—Gleadell inquired, "Who lives here?" The man replied simply, "Me, wife, and little dog."(19) | Long-time San Franciscan Charles Warren Stoddard told a story of how when his "‘special,' by the authority vested in him" demanded admittance to a particular closed door, "a group of coolies" who lived in the vicinity and had followed the tourists tried to divert his attention by assuring him that the place was vacant. The officer refused to leave, decided to employ force to open the door, and when he did, succeeded in revealing four sleeping men, "packed" into what Stoddard described as an "air-tight compartment" and "insensible" to the "hearty greeting" the tourists offered. W H. Gleadell related invading the living quarters of an impoverished Chinese couple—upon his police guide's instruction—in order to be able to take in such a scene firsthand. The officer enticed him with the statement, "'Now, if you would really wish to see how some of the lower class of Chinese live, this is not a bad place for the purpose. Go down that stair, push open the door at the foot, and walk right in.'" Armed with his guide's permission and his own sense of entitlement, Gleadell persevered. He came upon a room in which he was "just able to stand upright" and "with the exception of a stove in one corner" and some straw matting that "answered the purpose of a bed" was otherwise "quite destitute of furniture." At "one end crouched a man, while a woman sat in the centre, and a wretched little cur groveled between them." Then, "after a general survey"—complete with commentary on the "loathsome squalor" of Chinatown that was so typical of the tourist literature—Gleadell inquired, "Who lives here?" The man replied simply, "Me, wife, and little dog."(19) | ||

Latest revision as of 15:49, 27 May 2020

Historical Essay

by Barbara Berglund

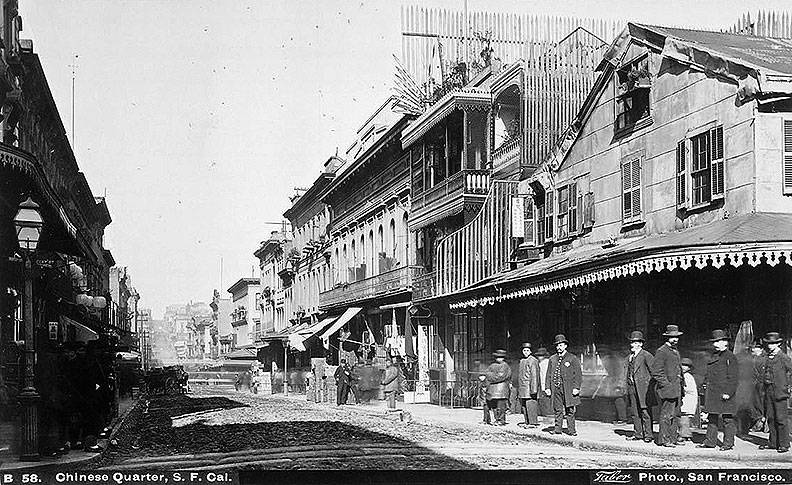

Busy Chinatown street corner, 1890s.

Photo: Bancroft Library, BANC-PIC-1985.084-125--ALB

Street scene, 1890s.

Photo: Online Archive of California

On May 18, 1886, a teenage girl identified only as E.G.H. arrived in San Francisco, one of many destinations on her trip through the West-perhaps with a Raymond Excursion Party—that had begun in Boston and included stops in Chicago, Kansas City, Santa Fe, Albuquerque, Los Angeles, Yosemite, and Mariposa. That day, from her "wonderful" accommodations at the city's luxurious Palace Hotel, she wrote to her "dear" Jay: "I am looking forward to my visit to Chinatown, where we are hoping to go in a day or two." Over the course of the next two weeks, E.G.H. made at least three trips into Chinatown, telling one recipient of her letters that she had "given as much time as possible to Chinatown" and was "fairly infatuated with the place."(l)

E.G.H.'s first foray into the neighborhood took place on her second evening in the city when she joined a "large party… made up to visit Chinatown." Upon reaching a certain corner the group was "suddenly joined by a Chinaman" named Chin Jun who-whether by accident or design-became their guide. Wearing the "costume of his country," including "a long pigtail hanging almost to his heels, with red silk braided in his hair," Chin Jun led this group of middle-class white American tourists "up a dark alley way to a Joss House," to the Chinese theater where they watched part of a play from seats in the gallery, and to a Chinese restaurant where they were "served with tea and sweetmeats, in true Celestial style." Although E.G.H. and her group "especially wanted" to see an opium den, Chin Jun refused, telling the group that it was simply too large. He spoke English "reasonably well," met their many questions with "a lovely smile," shared tea with E.G.H., and wrote his name for her in both English and Chinese as a souvenir. When Chin Jun was not leading white tourists around Chinatown, he worked as a clerk in a shop selling "fancy articles and curios" attractive to tourists. E.G.H. would encounter him again in this context and "make splendid bargains with him." In a letter relating her first Chinatown visit she declared, "I have lost my heart to Chin Jun."(2)

On her second visit, E.G.H was accompanied by Mrs. Law, a resident of the city whom she had been introduced to and who assured her that "she need not be afraid to go through Chinatown with her alone." Mrs. Law both knew the area and frequented it because of her association with friends doing missionary work in the neighborhood. Since E.G.H. was "quite ready to make any number of visits" to what she saw as a "curious and interesting place," she did not hesitate to accept Mrs. Law's offer and the two set off together. On their way they "passed through several dark and dirty alley ways, where men swarmed and stared," and as they traversed Chinatown's streets they "stopped to look at the curious things displayed in the markets." E.G.H. reflected that "as you walk through the streets of Chinatown you hardly realize yourself in America." During their excursion, E.G.H. paid another visit to a joss house where she learned more about Chinese religious practices than she had from Chin Jun, saw a woman with bound feet, heard tales of hidden gambling dens that made police raids so difficult, and went shopping-stopping at Chin Jun's store to purchase two Chinese musical instruments. Although E.G.H. noted that she "enjoyed this visit very much" she also indicated that she would "not be satisfied" until she had been to the opium dens.(3)

A few days later, E.G.H and four others "hired a detective" to take them "through Chinatown, and to the opium dens." Their guide took them "through streets and alley ways" and "down, down, along passageways, two feet wide, down another flight of stairs, along a narrow alley with doors opening into rooms not more than six feet square." In some of the rooms they passed they saw opium smokers reclining, in others they saw "Chinamen… eating their supper with chopsticks." At each encounter, the tourists nodded and said "Hello." At one point, the guide kicked open a door and led the group into a den "decorated with pictures and flowers" and occupied by "a Chinaman, with his pipe in hand." Although "somewhat under the influence of opium already" he greeted the tourists "pleasantly" and, at their request, provided a demonstration of the process of preparing and smoking opium. The group still desired to see "worse dens" so thanked the smoker and continued on, groping their way "through the filth and smell, upstairs, and then down again." It was not long before their guide forced open another door and the group was faced with a malodorous room crowded with people and animals. This sight prompted E.G.H. to reflect, “What is to be done with these Chinese is certainly a serious question. Forty-three thousand souls living in seven blocks!"(4)

E.G.H.'s account of her visits to Chinatown typified the kinds of tourist encounters that resulted from the fact that the most distinctly bounded ethnic enclave in nineteenth-century San Francisco—a product of virulent discrimination against Chinese immigrants—also functioned as a popular tourist destination for the city's visitors and a local place of amusement for its residents not unlike Woodward's Gardens, the Barbary Coast, or the Pacific Museum of Anatomy and Science. For the growing population of largely male laborers who made Chinatown their home, the neighborhood's community offered a relatively safe haven as well as networks of familiar people, institutions, goods, and services. As E.G.H.'s experience reveals, among the non-Chinese, Chinatown's appeal combined a number of overlapping impulses—the desire to see the exotic; the pull of an encounter with a different culture; the draw of slumming; and the attraction of experiencing, from a safe distance or with a police guide, racially charged urban dangers. This collision of the everyday cultures of an immigrant neighborhood and the tourist impulses of non Chinese visitors—scripted through the literature of Chinatown tourism and the practices of Chinatown guides—made Chinatown into a cultural frontier that wielded considerable social power. The particular images of Chinatown that nineteenth-century tourists read about, reported upon, often expected to see, and as a result often saw, reflected and shaped the very idea of what "Chinese" meant in San Francisco. As a cultural frontier on which key components of San Francisco's racial order were articulated and solidified, Chinatown worked in tandem with larger legal and political developments, providing an arena where whites and Chinese encountered one another face-to-face and from which many whites came away with what they believed were social truths about this new immigrant group.(5)

Tourist literature's representations racialized the Chinese in terms of their unassimilability, their proclivity toward vice, the risks they posed to public health, and the threat they presented free white labor. These representations dovetailed with the logic of a developing local racial hierarchy that placed the Chinese on the lowest rung as well as with larger policy debates about Chinese immigration.(6) Across class lines, whites positioned the Chinese below San Francisco's small population of blacks, the group that was typically positioned at the bottom of the racial ladder throughout much of the rest of the nation. As a result, "Chinese" and "white" rather than "black" and "white" emerged as the most potent racial opposites in the city, configuring its most highly charged racial divide. The way this process worked in San Francisco set important precedents for the nation as it was one of the first major American cities to incorporate a large Asian minority population. Moreover, while tourist literature's representations had particular significance within the locality of San Francisco, they also gave images of Chinatown and Chinese immigrants national and international circulation. E.G.H.'s account, for example, was published by a Boston press. Through these images, Chinese immigrants entered the racial imagination even in places where they had not settled and where people may have never actually seen an Asian person. As growing hostility in the West led increasing numbers of Chinese to settle and establish Chinatowns in cities such as New York and Boston, tourist literature generated templates of meaning that framed the way such developments would be received.

E.G.H. captured an incredibly wide range of the experiences available to and sought after by Chinatown tourists. She made sure to visit the four key sites of Chinatown's tourist terrain—restaurants, joss houses, opium dens, and theaters—and also took in some other popular, but nonetheless secondary, sights—women with bound feet, gambling dens, and shops. Like many tourists, her experiences occurred within nineteenth-century America's emergent Orientalism, which promoted a disdain for resident Asians but also a prurient fascination with a limited, largely manufactured, brand of Asian culture. The tension inherent in this kind of thinking about all things Oriental allowed E.G.H. to befriend Chin Jun and delight in Chinese food and wares while maintaining a perspective on Chinatown as utterly alien and believing her sojourn there would not be complete until she saw the Chinese displayed in stereotypically vicious pursuits.(7) Although representations of Chinatown more often than not worked to create a sense of insurmountable distance between Chinese and whites, the very presence of white tourists in Chinatown meant that on this cultural frontier real encounters between the two groups were taking place in ways that sometimes disrupted the dominant story—as the friendship between E.G.H. and Chin Jun attests—and at other times confirmed it. While Chinatown existed as a segregated space set apart from the rest of the city, its visitors and residents constantly negotiated a complicated dance of white social power and Chinese local knowledge that allowed both the tourist enterprise and the transgression of the racial boundaries that Chinatown represented to occur.

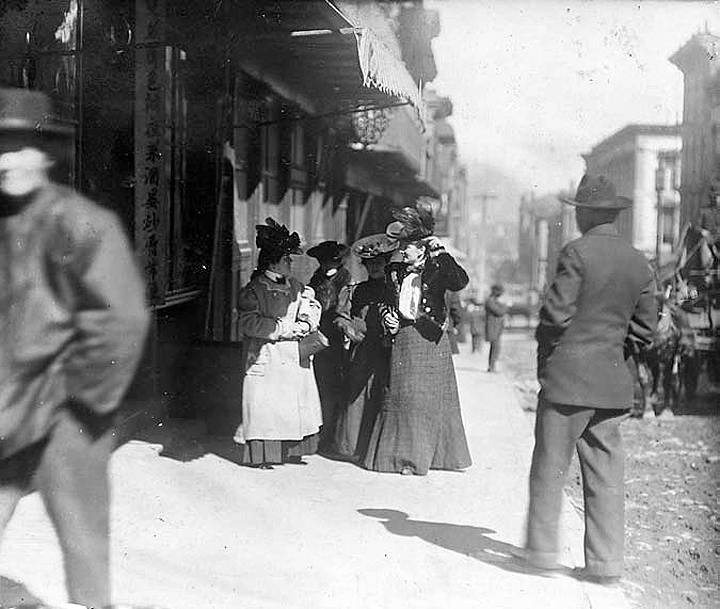

White women walking through Chinatown. Chinatown quickly emerged as a curiosity and an organized site of urban tourism for city visitors as well as non Chinese San Franciscans.

Photo: Chinese in California, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

When E.G.H.'s letters were published in 1887, a year after her trip, they joined a rapidly expanding body of literature genera ted to feed the appetite of a reading public fascinated by San Francisco's Chinese population and eager either to play the armchair tourist or to use writings about Chinatown to make preparations for a visit of their own. Tourism boomed during the second half of the nineteenth century as developments in transportation and communication made travel easier and a middle class emerged flush with the financial resources, leisure time, and inclination to explore America. Organized tours, like the one that steered E.G.H. through the West, responded to this demand and established itineraries of specific sites such as Chinatown, Yosemite, and Santa Fe-through which tourists came to understand the nation as well as their place in it. Whereas natural wonders and places of historical significance allowed tourists to define who they were and what they were a part of, the various peoples that became part of the tourist terrain-Mormons, Native Americans, Mexicans, and Chinese—were generally displayed and consumed in such a way as to reinforce their difference from and inferiority to the white tourists who gazed upon them. Writings about Chinatown emerged from within this larger context. Their depictions of the Chinese and Chinatown were shaped by the perceptions of various urban adventurers—often led by guides well versed in the tropes of the Chinatown experience—during forays into the neighborhood. In a circular relationship, for many readers—some of whom later became visitors—their perceptions and experiences of this cultural frontier were undoubtedly filtered through the tourist literature they consumed prior to their Chinatown excursions.(8)

The literature of Chinatown tourism constituted part of the urban exploration genre that generated popular and often luridly descriptive guides to nineteenth-century cities usually written from the point of view of a white, typically male spectator who traversed the city and recorded his voyeuristic observations with the kind of detached yet possessive authority that also characterized the consuming gaze of the typical tourist. It intersected stylistically with the reports of social reformers and policy makers; the studies of anthropologists and sociologists; as well as emergent forms of expose journalism—none of which were averse to doubling as platforms for voicing opinions on pressing social issues. E.G.H.'s detailed descriptions of vice and crowding in Chinatown followed by a pronouncement about the Chinese question, in this context, were hardly unusual.(9)

Chinatown tourist literature took a wide variety of forms. It could be found in small travel guides devoted exclusively to the Chinatown experience, sections about Chinatown in larger guides of the city or state, articles in magazines published nationally as well as in England, local newspaper stories, books about the Chinese in California that included chapters on Chinatown, and reminiscences that recalled Old Chinatown just after the earthquake and fire of 1906. Both women and men authored these writings and both seemed to have been equally comfortable taking on the voice of the tourist gaze in their narrations of the standard tropes of the Chinatown experience. Writers included San Francisco residents who frequented the neighborhood, journalists and tourists, and religious men whose missionary impulses brought them to Chinatown.

While some writers explored Chinatown on their own, many, like E.G.H, relied on guides to protect them from overly dangerous encounters and to provide the kind of experience necessary for writing a piece that would satisfy both their own and their readers' desires for thoroughness and authenticity. Although Chinatown tourists frequently wanted to view an itinerary of predetermined sites, they did not necessarily seek out prepackaged experiences. Wandering through restaurants and joss houses, for example, they often encountered Chinese going about their everyday activities and many of what seemed like the most staged experiences often involved barging in on people and catching them unprepared for the tourist gaze.(10) Hired guides—whether drawn from the ranks of the city's police force, white men who had gone into business for themselves, or Chinese entrepreneurs—facilitated these experiences. They were not only widely available, but some advertised their services and much of the tourist literature encouraged their use.(11) The demand for Chinatown guides was fueled in part by tourist literature's frequent emphasis, often in quite dramatic language, of the risks involved when a tourist attempted to explore Chinatown alone, especially at night. Whether it was truly dangerous, a ploy designed to drum up business, or a by-product of the salaciousness of the urban exploration genre, the discourse was ubiquitous. W H. Gleadell, in a piece written originally for Gentleman's Magazine and republished in the digest Eclectic Magazine, characteristically intoned, "Many places there are in this miniature China of San Francisco… to which no European has ever been admitted, or, if admitted, he has never survived to return to the world." Gleadell's recent tourist experience did allow him to concede that there were "certain parts" of Chinatown "which, at his own risk, the white man is free to traverse" but insisted that "in no case is it prudent to visit even these without the escort of a properly armed police officer well known on the Chinatown beat." Of salience for women adventurers, tourist literature refrained from casting Chinatown danger in sexualized terms. Characterizations of Chinese men as either objects of white women's desire or as lascivious predators that Chinatown fiction sometimes developed were largely absent from this ostensibly more realistic genre. In general, tourist literature tended to desexualize Chinese men in ways that opened the possibility for white women to hire them as guides and feel safe traversing the neighborhood with them.(12)

While many Chinatown guides were white men—sometimes but not always affiliated with the police—some were local Chinese, like E.G.B.'s guide, Chin Jun. Just as he seemed to have appeared out of nowhere, the product of a chance encounter—unlike white guides, who tended to be arranged by appointment—local writer Will Irwin described being led through Chinatown's legendary labyrinthine passages by a Chinese guide who announced both his presence and his intentions with the statement, "I take you." Another San Francisco resident, guidebook author William Bode, explained this tendency of white tourists to simply stumble upon Chinese guides in a way that suggests that participating in this nascent yet burgeoning tourist economy was a money-making opportunity not lost on local Chinese. He explained that, "Solicitations are made, at every crossing, to guide and conduct you to the various shrines and objects of curiosity, which abound here." Perhaps guiding tourists was lucrative enough to outweigh conforming to the stereotypes of the tourist terrain. Perhaps taking some control of the touring process away from white police allowed Chinese guides to disrupt, rather than reinforce, the racial stereotypes at the heart of tourists' expectations.(13)

For tourists, employing a Chinese guide meant having an experience on Chinatown's cultural frontier that was markedly different from simply wandering through Chinatown and gazing upon its Chinese inhabitants. It required engaging in a relationship with a Chinese person. Such a relationship was financial-the guide was hired to perform a service, it involved communication and conversation, it positioned the guide as the local expert, and it implied a certain amount of trust, given that the guide was leading the tourist into ostensibly dangerous areas. Granted, few tourists developed the kind of fondness for their guide that E.G.H. expressed for Chin Jun, but her experience presented one point on a continuum of possibility. Eleanor B. Caldwell's experience, captured in a piece that circulated in at least two national periodicals in the 1890s, offered another. She related that at the end of a long day touring Chinatown she stood on the balcony of a Chinese restaurant after taking a meal while her guide confided to her party "in a debonair way, and with remarkable English, his views of life and of his own career, the belief that he, 'John Chinaman,' might make a political leader if like Boss Buckley, he but owned a fine trade in the saloon line!" Caldwell scoffed at her guide's ambitions to become a player in local Democratic politics—highlighting in her tone the ridiculousness of such a proposition—and it was possible that her guide was making a joke by claiming for himself a completely absurd goal given the climate created by the Chinese Exclusion Act. Nevertheless, the two engaged in a conversation in which a Chinese man conveyed to a white woman his desire for a civic identity. Not only did this represent a level of discourse considerably beyond that required to explain Chinatown's sites to a party of tourists but it also presented a Chinese man as having aspirations like any other man-even if they were both belittled and denied.(14)

Balcony of the Chinese Restaurant, Dupont Street, San Francisco—perhaps like the one on which Eleanor Caldwell conversed with her guide.

Photo: I. W Taber, photographer. Chinese in California, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

In gathering information for their joint effort of 1898, Ten Drawings in Chinatown, Ernest C. Peixotto and Robert Howe Fletcher also employed a Chinese guide. Apparently, despite the fact that both men were San Francisco residents and Peixotto was a well-known illustrator of Chinatown scenes, the two found themselves "making inappropriate inquiries in all sorts of strange places" during their "search through Chinatown for information and bric-a-brac." "It was in this way," they informed their readers, "while asking for silk in a tea store, that we accidentally made the acquaintance of Wong Sue." Wong Sue, one of a number of men in the shop, eventually came to the aid of Peixotto and Fletcher by acting as a translator for the two, who were struggling to communicate with the Chinese shopkeeper in English. Despite Wong Sue's initial hesitance, Fletcher recorded that, "His aid once having been tendered he proved very obliging and after explaining to us the nature of the shop we were in, volunteered to lead us to another where we could procure what we desired." The two white men, self-described as "Author and Artist," then proceeded to explain their purpose to Wong Sue. "We told him how Chinatown and the Chinese interested us and how odd and amusing many of their customs seemed to us…that we proposed to tell what was bad as well as good." Wong Sue listened silently, and then said: "I think maybe you tell the truth, that will be very good." So, Peixotto and Fletcher "started out to find the artistic truth of Chinatown under the guidance of the wise Wong Sue."(15)

From the start, Wong Sue's very willingness to serve as their guide—however initially reluctant he may have been—flew in the face of Peixotto and Fletcher's notions of the "Chinese character." "As a rule," they informed their readers, "the inhabitants of Chinatown are reserved, secretive, irresponsive and impenetrable in the presence of strangers. Each seems to have erected a little Chinese wall around his personality." But Peixotto and Fletcher did not see this reticence as entirely out of line given "the surveillance under which they live, the constant apprehension that the friendly stranger may at any moment throw open his coat and display a silver star, that dreaded emblem of law totally at variance with all their traditions and whose workings they do not comprehend." While dealing with an often hostile and corrupt police presence was an unfortunate fact of life in Chinatown, the notion that the Chinese in Chinatown were so bound to foreign tradition that they were unable to understand the procedures of American law enforcement was shown to be facetious when Wong Sue revealed a previously hidden facet of his identity. During their travels in Chinatown, Peixotto and Fletcher related to their readers that they "almost invariably enjoyed the distinction of being taken for country detectives." They knew that "every city detective and police officer" was known to the inhabitants of Chinatown but they also noticed that Wong Sue "seemed well known to the police." Images of Chinese criminals began to dance in their heads and they "began to wonder if our amiable guide was a 'high-binder' or professional murderer in disguise." Finally, Peixotto divulged their suspicions, "point blank." "What makes you think so?" asked Wong Sue calmly. Peixotto "explained that he seemed suspiciously well known to the officers of the law." "That," replied Wong Sue, "is because I'm a policeman, myself." And opening his blouse, sure enough, there was the star.(16)

In the tale they wove, Peixotto and Fletcher's encounter with Wong Sue effectively upended a number of their stereotypes about the Chinese. On one level, at least, they stood corrected. On another, however, their story further inscribed racializing stereotypes by making Wong Sue the exception that proved the rule. This double-edged quality, of reveling in some stereotypes about the Chinese even as they overturned others, also ran through Peixotto and Fletcher's clever inversion that gave Wong Sue access to a major source of power in Chinatown—the police-and made him part of the apparatus of surveillance rather than simply one of the regularly surveilled. That revealing himself to be an officer of the law was so surprising only made sense in a context in which that would seem as nearly as out of the ordinary as Eleanor B. Caldwell's guide aspiring to be the machine politician, "Boss Buckley." Yet, while all of these encounters—to varying degrees—revealed prevailing prejudices, nevertheless, at the base of all three was the fact that a middle-class white person and a Chinese person had spent the better part of a day conversing and roaming around together—something that was unlikely to happen outside the bounds of Chinatown's cultural frontier.

While Peixotto and Fletcher's account ultimately left a lot to be desired in terms of their understanding of the "Chinese character," they thoroughly succeeded in capturing the reality of the police presence in Chinatown. White visitors' use of police guides added another level of surveillance to the police presence already in the area. Tourists, after all, often chose police guides not just because of safety concerns but also for the knowledge of and access to Chinatown they could provide—a by-product of their constant presence. When tourist J.W. Ames visited Chinatown one evening in the company of a police guide, he described for readers of the article he wrote for Lippincott's the kind of rapport this Chinese-speaking officer had with the local community as they strolled down Jackson Street, effectively capturing both familiarity and a kind of deference that could just as likely be born of fear as admiration. "The sidewalks are thronged with passers, who all seem to know the officer," he wrote, "for they jump aside and bow with unfeigned respect. The officer now and then hails one, and sometimes pauses to carry on a short conversation." Bancroft's Tourist Guide also hinted at the inequality that permeated the tourist enterprise when it recommended a particular officer as a guide precisely because "his long experience" among the Chinese has "acquainted them with him to such a degree, that they allow him to enter and pass through their houses and rooms whence another might be shut out." That policemen were "allowed" into Chinese living spaces might have been part of a bargain struck between the tour guide and the toured upon in which each took a share of the profits or it might have been, more baldly, a product of police domination of the neighborhood. An account in London's Cornhill Magazine leaned bluntly toward the latter explanation, attributing the possibility of these kinds of intrusions to the fact that the Chinese had been "so thoroughly… cowed by the San Francisco police" that they were unable "to utter the faintest exclamation of annoyance." Even if reality tended toward some combination of Chinese agency and police power, the prevalence of these kinds of intrusions and the use of police guides meant that the power relations that existed between the police and the Chinese community framed this aspect of the tourist experience of Chinatown.(17)

Police guides, moreover, were known for deploying quite brutal, invasive, and generally disrespectful tactics that included kicking doors open, forcing their way into private living quarters, waking people from sleep, and shining bright lights into people's faces. Whether these encounters were staged or not, they made violence an expected part of the tourist experience in Chinatown. Local photographers capitalized on these expectations and sold souvenir photographs that claimed to "show the Chinaman taken by surprise, as the flash light illuminates his den." Photographer Henry R. Knapp packaged his series of such images in a three-inch square booklet, which made them easily portable and well suited for carrying in one's pocket or purse. The scenes he captured and captioned included the expected "Opium Den" and "Filling Opium Pipe," but the inclusion of "Old Blind Chinese Woman, Aged 77" and "Trimming His Corns" disclosed tourists' appetite for being let into private moments, not just vicious ones.(18)

These images were packaged with others in a three-inch-square book let designed to be easily portable, well suited for carrying in a pocket or purse. While "Opium Den" (top left) and "Filling Opium Pipe" (top right) presented expected tropes of the tourist terrain, "Old Blind Woman" (bottom left) and "Trimming His Corns" (bottom right) revealed the desire of tourists to view—and the power of the photographer to capture—ostensibly private, domestic scenes as well as vicious ones.

Photos: Henry R. Knapp, 1889. Huntington Library

Long-time San Franciscan Charles Warren Stoddard told a story of how when his "‘special,' by the authority vested in him" demanded admittance to a particular closed door, "a group of coolies" who lived in the vicinity and had followed the tourists tried to divert his attention by assuring him that the place was vacant. The officer refused to leave, decided to employ force to open the door, and when he did, succeeded in revealing four sleeping men, "packed" into what Stoddard described as an "air-tight compartment" and "insensible" to the "hearty greeting" the tourists offered. W H. Gleadell related invading the living quarters of an impoverished Chinese couple—upon his police guide's instruction—in order to be able to take in such a scene firsthand. The officer enticed him with the statement, "'Now, if you would really wish to see how some of the lower class of Chinese live, this is not a bad place for the purpose. Go down that stair, push open the door at the foot, and walk right in.'" Armed with his guide's permission and his own sense of entitlement, Gleadell persevered. He came upon a room in which he was "just able to stand upright" and "with the exception of a stove in one corner" and some straw matting that "answered the purpose of a bed" was otherwise "quite destitute of furniture." At "one end crouched a man, while a woman sat in the centre, and a wretched little cur groveled between them." Then, "after a general survey"—complete with commentary on the "loathsome squalor" of Chinatown that was so typical of the tourist literature—Gleadell inquired, "Who lives here?" The man replied simply, "Me, wife, and little dog."(19)

These two scenarios captured a series of extraordinarily revealing moments. In the first, Chinatown residents unsuccessfully tried to foil police efforts to gain entry into Chinese living quarters. A police guide used force to open a door and woke several sleeping Chinese men. The tourists he was leading then offered these men a greeting. In the second, a tourist—under the direction of a police guide—barged into the residence of a Chinese couple, made observations, and asked the occupants questions. And it is easy enough to add a third by revisiting E.G.H.'s final Chinatown visit in which her guide kicked open one door to reveal an opium smoker and forced open another to present a view of crowding and squalor—providing her with a very different kind of experience than her day with Chin Jun, who had refused to take her party to the opium dens. Although gazing upon other people and landscapes was part of any tourist experience, not all tourist experiences involved this kind of evaluation of a subordinate group by a dominant group. Even if these scenarios were staged and the local participants received some compensation from the guides for their role in these presentations of Chinatown, this does not diminish the social potency of these kinds of events. The violent invasions of the police guides, the boldness of a tourist like Gleadell, and the ways tourists scrutinized the Chinese and spoke to them could only be considered acceptable in a situation in which tourists viewed the toured upon as their inferiors. Chin Jun's refusal to take E.G.H. to an opium den and the attempt by bystanders to waylay the police from one of their raids also suggest that the degrading effects of these components of Chinatown's cultural frontier were not lost on neighborhood residents.

One chronicler of the Chinatown tourist experience, Reverend Otis Gibson, who had considerable knowledge of local practices from the vantage point of his long career as a missionary in the neighborhood, tried to draw tourists' attention away from the derogatory image of the Chinese being constructed for their consumption to the unfavorable image that such practices actually presented of white Americans and their culture. Gibson related an especially violent story of "one of these night excursions" in which a policeman, acting as a guide to a party of ministers, upon entering the living quarters of some of Chinatown's residents, "pulled away the apology for a curtain from before the miserable hole in which a poor Chinaman was peace fully sleeping." In order to give the ministers a better view, the police guide "then brought the full glare of his lamp upon the face of the sleeper." The man "feeling annoyed naturally growled his dissatisfaction." With that, the "policeman for the delectation of those pious men seized the poor fellow and brutally pounded and punched his head with his …fist." Gibson then concluded, tongue in cheek, "How our civilization must shine in the eyes of those poor underground Chinamen!"(20)

Gibson also explained to readers that there was a real problem with the way the "'special policemen'" were "always ready to take visitors through these dens, to show them 'the Chinese as they are.'" Visitors, as a result, would "go away and write up 'the Chinese in America,' giving as historical facts the impressions received from such a night adventure." Not only did Gibson openly "protest against this method of studying the Chinese Question"—the effects of which were rampant in the tourist literature—but he also played the devil's advocate with his readers. "Suppose the tables turned," he wrote, "and curious Chinamen escorted by some 'kind and intelligent policeman' should make a raid upon American bedrooms, about twelve or one o'clock at night, solely for the delectation of the Chinamen, and so that some Chinese correspondent could write sensational letters to the Pekin Gazette." "How," Gibson asked, "would the shoe fit on that foot? One might as well write up 'The Americans as They Are' from a visit to the Five Points in New York."(21)

Yet even without a police escort, tourists would go to great lengths to see the sights required to fulfill their Chinatown experience and some were not averse to employing boldly invasive and downright rude tactics of their own. "It is about four o'clock in the afternoon; we pass through the dirty alley, lined on each side with a dirtier door in which a window sash forms the upper portion and low windows with panes of glass six by eight in size," reported one of the Chronicle's journalists. "We impudently peep through the first we come to." A story in the Alta related similar tourist behavior on the pan of a young woman during Chinese New Year celebrations. "We followed the example of everyone else, and peered in at all the windows, or stood in the open doors, which was very rude of us, of course, but still we did it, until finally we were snubbed." J. Torrey Connor, a journalist who wrote up his experience for publication in the Chautauquan, related tagging along behind "a party of sightseers, at the heels of a professional guide," following them down a dark passage, and pushing open a door that had "been carelessly left ajar."(22)

In their visits to Chinatown, tourists—as they were led around by police guides and local Chinese and as they traipsed around on their own—participated in a range of activities that put them in different relationships with and proximities to Chinatown and its inhabitants. E.G.H. was not alone in being able to forge the kind of relationship with a Chinese person required to engage a Chinese guide, then to later be led around by a police officer who broke down the doors of local Chinese, and at other times to stroll and explore essentially on her own, perhaps also peering into windows as she went. Each way of taking in Chinatown brought with it varied experiences from which different meanings could be made about the place and its inhabitants. Yet as varied as the activities and ways of seeing were, they were powerfully framed by the literature of Chinatown tourism and the practices of Chinatown guides, which not only identified particular sights for tourists to see, but informed them what they were supposed to mean.

In the tourist literature, Chinese restaurants, for example, were portrayed as violating norms of public health as well as various food taboos; opium dens were used to conjure images of Chinese as particularly prone to vice; joss houses were described in ways that emphasized unassimilability and difference in the form of heathenism; and theaters were employed to illuminate issues about Chinese laborers and the backwardness of Chinese culture. The overall picture fortified the image of Chinese immigrants as utterly alien, insurmountably different, and from a culture that was considerably less evolutionarily elevated than that found in nineteenth-century America. The themes of unassimilability, contamination, labor competition, and vice were nodes around which the nineteenth-century image of "the Oriental" was structured in the dominant culture's imagination. Rather than constructing completely novel images of Chinese immigrants, tourist literature mobilized and elaborated upon themes already in circulation. In the decades prior to the gold rush, the Chinese immigrants who had come to the United States settled mainly on the Eastern seaboard and were generally viewed as exotic curiosities. The unprecedented numbers of Chinese immigrants that arrived in San Francisco prior to the Exclusion Act, however, could not be understood through definitions that linked difference with notions of visitors from a distant, far away land. Instead, they necessitated a more direct subordination through cultural ordering that positioned Chinese immigrants within the nation's operative racial hierarchies and was informed by representation of "the Oriental" as a permanent, threatening, and alien presence.(23)

One of the main ways Chinatown was represented in the tourist literature was as a foreign place. As early as 1859, Reverend J. C. Holbrook observed that there were "parts of two or three streets" in San Francisco where one could "get a very good idea of Canton." On her trip in 1886, E.G.H. had reflected that, "As you walk through the streets of Chinatown, you hardly realize yourself in America." Emphasizing that the Chinese community was in America, but not of America, reinforced notions of the Chinese as an unassimilable and alien people. Many writers, in fact, were so convinced in advance by tourist literature of the foreignness of the overall setting, they had a hard time assimilating the not-so-foreign aspects of Chinatown. As a result, tourist literature often downplayed things that pointed to the interpenetration of Chinese and American cultures—bilingualism and American style dress, for example—that might unsettle tourists' expectations. Yet when representations of Chinatown as a foreign place mobilized images associated with an exotic Orient, they lacked the comfort provided by distance. Whatever similarities authors of travel literature chose to draw, Chinatown was not Peking or Canton—a foreign land filled with foreign people visited briefly by the Euro-American tourist. Rather, Chinatown, as many accounts pointed out, was a segregated space located in the heart of an American city and the Chinese who inhabited it were not colorful foreigners "over there" but men acing aliens "over here."(24)

Layered on top of the representation of Chinatown as a foreign place—and just as prevalent—were unfavorable descriptions of the public health of Chinatown that focused particular attention on its overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and malodorousness as well as its dark alleys and legendary underground passages in which it was imagined that all sorts of dirt and vice were hidden away. G. B. Densmore, author of the anti-immigration tract The Chinese in California, announced, both simply and typically: "The Chinese Quarter is very filthy. They have in the alleys and around their houses… old rags, slop-holes, excrement, and vile refuse animal matter. They are compelled by the police to clean up, or they would be buried in their own filth." That the crowding and lack of public sanitation in Chinatown were in large measure products of the poverty of its residents coupled with the denial of basic municipal services was of little interest. The discussions of the quality of public health in Chinatown found in the tourist literature were not exposes designed to bring middle-class aid to the neighborhood. Instead, the representations of Chinatown as a foreign place that was teeming, filthy, squalid, and smelly worked to racialize Chinese immigrants as literal pollutants-the social and cultural opposites of clean, virtuous, civilized white Americans. For many tourists, being an eyewitness to aspects of life in Chinatown that supported this representation of Chinese immigrants was not an accidental occurrence or something to be endured but actually a sought-after component of the tourist experience. When one journalist for the Chronicle, for example, paid a second visit to "the dens… located in the vicinity of Cooper's alley" in the company of "officer Woodruff," he seemed to revel in revealing that "the place seems even more disgusting than on our first visit; the stench more in tolerable; the rough board flooring more uncertain and dangerous."(25)

Notes

1. E.G.H., Surprise Land: A Girl's Letters from the West (Boston: Cupples, Upham, 1887), 75, 94. San Francisco's Chinatown is the oldest and largest Chinese community in the United States. It has remained a popular tourist attraction for visitors to San Francisco as well as an essential component in the city's tourist industry. See Chalsa M. Loo, Chinatown: Most Time, Hard Time (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1991), 3-21.

2. E.G.H., Surprise Land, 76-80.

3. Ibid., 83.

4. Ibid., 96-99

5. For histories of Chinese American communities and the struggles of Chinese Americans against racism and discrimination, see, for example, Sucheng Chan, ed., Entry Denied: Exclusion and the Chinese Community in America, 1882-1943 (Philadelphia:Temple University Press, 1991); Gary Okihiro, Margins and Mainstreams: Asians in American History and Culture (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994); Ronald Takaki., Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans (New York: Penguin Books, 1989); Sucheng Chan, Asian Americans: An Interpretive History (Boston: Twayne, 1991); Charles J. McClain, In Search of Equality: The Chinese Struggle against Discrimination in Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994); Yang Chen, Chinese San Francisco, 1850-1943: A Trans-Pacific Community (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000); Erika Lee, At America's Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882-1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); Roger Daniels, Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States since 185o (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988); and Judy Yung, Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

6. The workings of the process of racialization are delineated in Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1980s, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1986). See also Tomas Almaguer, Racial Faultlines: The Historical Origins of White Supremacy in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), and Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

7• Several recent works have drawn on Edward Said's scholarship to explore American variants of Orientalism. See Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1979); Robert G. Lee, Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999); John Kuo Wei Tchen, New York before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture, 1776-1882 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999); Anthony Lee, Picturing Chinatown: Art and Orientalism in San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 20m); Malini Johar Schueller, U.S. Orientalisms: Race, Nation, and Gender in Literature, 1790-1890 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998); and David Palumbo-Liu, Asian/American: Historical Crossings of a Racial Frontier (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999).

8. In many respects, Chinatown tourism defined tourists as "American" and "citizens" and the Chinese as squarely outside the bounds of those categories. For a discussion of the way tourism has functioned "as a ritual of citizenship" for white Americans, see Marguerite S. Schaffer, See America First: Tourism and National Identity, 1880-1940 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001), 225. See also David Wrobel and Patrick T. Long, eds., Seeing and Being Seen: Tourism in the American West (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001 ). For discussions of international tourism in postcolonial and colonial contexts, respectively, that have relevance for the tourist-toured upon relationship in the internal colony of Chinatown, see Malcolm Crick, "Representations of International Tourism in the Social Sciences: Sun, Sex, Sights, Savings, and Servility," Annual Review of Anthropology 18 (1989), 307-344, and Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (New York: Routledge, 1992 ).

9. My understanding of the literature of urban exploration is informed by the discussion of urban spectatorship in Judith R. Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late Victorian London (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 15-39• Both guides who led tourists around and the tourist literature that prepared tourists for what to expect to see facilitated the "collection of signs" that made up the detached, differentiating "tourist gaze" that tourists deployed in their consumption of Chinatown. See John Urry, The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies (London: Sage Publications, 1990), 3, and Consuming Places (London and New York: Routledge, 1995). Chinatown tourism was less about pleasure and leisure than many of the sites Urry identifies, but the gaze itself was similarly objectifying. For a compelling discussion of the way a "collection of signs" in the form of objects can manifest more claims on what is real than they actually possess, see Eric Gable, Richard Handler, and Anna Lawson, "On the Uses of Relativism; Fact, Conjecture, and Black and White Histories at Colonial Williamsburg," American Ethnologist 19, no.4 (November 1992): 791-805.

10. For the classic discussion of "staged authenticity," see Dean MacCanell, The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class (New York: Schocken Books, 1976). See also Raymond Rast, "Staging Chinatown: The Place of the Chinese in San Francisco's Tourist Industry" (unpublished paper in author's possession).

11. For works advocating or referring to the use of guides see, for example, Isaiah West Taber, Hints to Strangers (San Francisco: Taber, 188-), 3; Disturnell's Strangers' Guide to San Francisco and Vicinity: A Complete and Reliable Book of Reference for Tourists and Other Strangers Visiting the Metropolis of the Pacific (San Francisco: W. C. Disturnell, 1883), 108-109; "Seeing the Sights," Century Illustrated Magazine 65, no. 6 (April 1903): 101; B. E. Lloyd, Lights and Shades in San Francisco (San Francisco: A L. Bancroft, 1876), 262-263; "San Francisco's Chinatown," in Seen by the Spectator; Being a Selection of Rambling Papers First Published in the Outlook, under the Title The Spectator (New York: Outlook, 1902); D. E. Kessler, "An Evening in Chinatown," Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine 49, no. 5 (May 1907): 445; Eleanor B. Caldwell, "The Picturesque in Chinatown," Arthur's Home Magazine 65, no. 8 (August 1895): 653, and New Petersen Magazine 4, no. 1 July 1894): 595 (subsequent references to this source refer to Arthur's Home Magazine); Charles Warren Stoddard, A Bit of Old China (San Francisco: AM. Robertson, 1912), as excerpted from In the Footprints of the Padres (San Francisco: A.M. Robertson, 1901 ); and Bancroft's Tourist Guide (San Francisco: A. L. Bancroft, 1871). While a number of sources suggest that there was some sort of licensing procedure for guides, the details of that system have not revealed themselves. See, for example, Joseph Carey, D.D., By the Golden Gate or San Francisco, the Queen City of the Pacific Coast: With Scenes and Incidents Characteristic of Its Life (Albany, New York: Albany Diocesan Press, 1902), 138-140; William Bode, Lights and Shadows of Chinatown (San Francisco: H. S. Crocker, 1896); and Helen Throop Purdy, San Francisco as It Was, as It Is, and How to See It (San Francisco: Paul Elder, 1912).

12. W H. Gleadell, "Night Scenes in Chinatown," Eclectic Magazine (September 1895): 378-383, quote from 379• For examples of other cautionary tales about what could happen if one ventured off the beaten path in Chinatown, see Rudyard Kipling, Rudyard Kipling's Letters from San Francisco (San Francisco: Colt Press, 1949), 31-32; Frank Norris, The Third Circle (New York: John Lane, 1909); and Emma Frances Dawson, "The Dramatic in My Destiny," Californian I, no. 1 January 1880): I-II. If estimates were correct—from $1 per person to $2-$3 per hour—guides would have been affordable for the middle classes that made up the bulk of the tourist trade. See Carey, By the Golden Gate, 138-140 and JohnS. Hittell, A Guidebook to San Francisco (San Francisco: Bancroft, 1888), 50. For ways Chinese men were sexualized in relation to white women see Lee, Orientals, 83-105.

13. Will Irwin, ed. Old Chinatown: A Book of Pictures by Arnold Genthe (New York:

Mitchell and Kennerly, 1980), 154-155; Bode, Lights and Shadows, npn. Writers have disagreed about the existence, or at least extent, of Chinatown's underground labyrinths. For example, Louis Stellman contended that "as for the human rabbit warrens supposed to exist under Chinatown, the great fire of 1906 utterly disproved this canard." See Louis J. Stellman, Chinatown: A Pictorial Souvenir and Guide (unpublished manuscript, 1917), 31, as well as Purdy, San Francisco as It Was, 137-138. Will Irwin, however, argued that the board of health had "filled in passage after passage" to prevent epidemics prior to the earthquake and fire. See Irwin, Old Chinatown, 153-155.

•

14. Caldwell, "Picturesque in Chinatown," 662.

15. Ernest C. Peixotto, Ten Drawings in Chinatown with Certain Observations by Robert Howe Fletcher (San Francisco: AM. Robertson, 1898), 1-2.

16. Peixotto, Ten Drawings, 4-5.

17. J. W. Ames, "A Day in Chinatown," Lippincott's Magazine (October 1875): 499; Bancroft's Tourist Guide, 215; "'China Town' in San Francisco, by Day and by Night," Cornhill Magazine, 56.

18. For a brilliant discussion of the way the staged touristic presentations of the physical body construct difference, see Jane C. Desmond, Staging Tourism: Bodies on Display from Waikiki to Sea World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). Quotation and Figures 19-22 are from a booklet of photos tided Chinatown, published by Henry R. Knapp, San Francisco, 1889. These same photos were pasted into A E. Browne's unpublished, handwritten travel journal to illustrate her experiences. A. E. Browne, A Trip to California, Alaska, and the Yellowstone Park, vol. (unpublished travel journal, ca. 1891). Photographs with a similar pedigree also accompanied "The 'Labor Question' on the Pacific Coast," Harper's Weekly (October 13, 1888): n8.

19. Stoddard, Bit of Old China, 7-8; Gleadell, "Night Scenes in Chinatown," 38r. See also Lloyd, Lights and Shades, 262-263.

20. Rev. 0. Gibson, AM., The Chinese in America (Cincinnati: Hitchcock and Walden, 1877), 93-94.

21. Gibson, Chinese in America, 93-94•Gibson had established a Methodist Episcopal mission in Chinatown in 1868. He was involved, among other things, in the creation of a mission school and in activities to provide sanctuary for Chinese prostitutes. See Chen, Chinese San Francisco, 77, 131, 134, 140-141.

22. "Horrors of a Great City: Chinatown by Day and Night," San Francisco Chronicle , December 5, 1869; Walter Turnbull, scrapbook of clippings of San Francisco area affairs: telegrams, drawings, letters to and from Turnbull (1882-1885), Rare Book Department, California Scrapbook, 27, Huntington Library. Contains at least one letter from 1890. Newspaper clippings omit years, but have dates. Sunday, February 22, Alta California Publishing Company/Daily Alta California; J. Torrey Connor, "A Western View of the Chinese in the United States," Chautauquan: A Weekly Newsmagazine 32, no. 4 January 1901): 378.

2 3. This understanding of "the Oriental" is drawn from Lee, Orientals, 8 -9, 27-3 2. Lee identifies four aspects of "the Oriental" in nineteenth-century American culture—the pollutant, the coolie, the deviant, and the yellow peril—which are constructed around issues of unassimilability, public health and sanitation, labor competition, and vice.

24. Rev.]. C. Holbrook, "Chinadom in California," Hutchings' Illustrated California Magazine 4 (1859-1860): 130. For reference to the foreign-ness of Chinatown, see also Carey, By the Golden Gate, 136-137; Bode, Lights and Shadows of Chinatown, npn; Lucien Biart, My Rambles in the New World, trans. Mary de Hauteville (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, 1877), 83-84; G. B. Densmore, The Chinese in California: Description of Chinese Life in San Francisco, Their Habits, Morals, and Manners, illustrated by Voegtlin (San Francisco: Pettit and Russ, 1880), 21; William Doxey, Doxey's Guide to San Francisco and the Pleasure Resorts of California (San Francisco: At the Sign of the Lark, 1897), 116-117; "Chinese Highbinders," Harper's Weekly (February 13, 1890): 103; C. Baldwin, "A Celestial Colony," Lippincott's Magazine (February 1881): 23; "'China Town' in San Francisco," 50; Gleadell, "Night Scenes in Chinatown," 1895, 379; "The Chinese in San Francisco," Harper's Weekly (March 20 , 1880): 182; "Lenz's World Tour," Outing, An Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Recreation 22, no. 5 (August 1893): 363; Connor, "Western View of the Chinese," 374; Kessler, "Evening in Chinatown," 445; Caldwell, "Picturesque in Chinatown," 653; Will Brooks, "Fragment of China," Californian 6, no. 31 July 1882): 2; New California Tourists' Guide to San Francisco and Vicinity (San Francisco: Samuel Carson, 1886), 59; Mabel C. Craft, "Some Days and Nights in Little China," National Magazine (November 1897), 100, 109; Charles Keeler, San Francisco and Thereabout (San Francisco: California Promotion Committee, 1902), 65; George Hamlin Fitch, "The City by the Golden Gate" Chautauquan 23, no. 6 (September 1896): 666; Lloyd, Lights and Shades, 2 36; and AM., "A Glimpse of San Francisco," Lippincott's Magazine June 1870): 645.

25. For an extended analysis of the way public health and race came together in Chinatown, see Nyan Shah, Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco's Chinatown (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001). Densmore, Chinese in California, 1880. Also, Gibson, Chinese in America, 63-64; Willard B. Farwell, The Chinese at Home And Abroad: Together with the Report of the Special Committee of the Board of Supervisors of San Francisco on the Condition of the Chinese Quarter of That City (San Francisco: A. L. Bancroft, 1885), 53-54, 59; and "Horrors of a Great City."

Originally published in chapter 3 “Making Race in the City: Chinatown's Tourist Terrain” in Making San Francisco American: Cultural Frontiers in the Urban West, 1846-1906 by Barbara Berglund (University Press of Kansas: Lawrence KS 2007)