Turning Sand Into Golden Gate Park: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(added photo) |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2014'' | ''Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2014'' | ||

[[Image:Astroturf-soccer-field 20161229 181221.jpg]] | |||

'''The new recycled tire athletic fields, now brightly lit at night in ways that also disturb local bird life.''' | |||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2016'' | |||

Fortunately, San Francisco ignored the conventional wisdom and set about the task of creating America's finest urban park. The two chief requirements were fertilizer and water; the latter was piped in and distributed with the help of the [[Windmill|Dutch Windmill]] that still stands by the ocean near where John F. Kennedy Drive hits the Great Highway, while the former was provided in the form of the copious droppings generously bestowed upon the City's streets by the drays who were, until the 1920's, the mainstay of the local transportation system. Though no reliable estimate of the amount of horse-excrement collected for park fertilizer exists, the total undoubtedly ran into tens, even hundreds of thousands of tons. | Fortunately, San Francisco ignored the conventional wisdom and set about the task of creating America's finest urban park. The two chief requirements were fertilizer and water; the latter was piped in and distributed with the help of the [[Windmill|Dutch Windmill]] that still stands by the ocean near where John F. Kennedy Drive hits the Great Highway, while the former was provided in the form of the copious droppings generously bestowed upon the City's streets by the drays who were, until the 1920's, the mainstay of the local transportation system. Though no reliable estimate of the amount of horse-excrement collected for park fertilizer exists, the total undoubtedly ran into tens, even hundreds of thousands of tons. | ||

Revision as of 14:09, 12 May 2020

Unfinished History

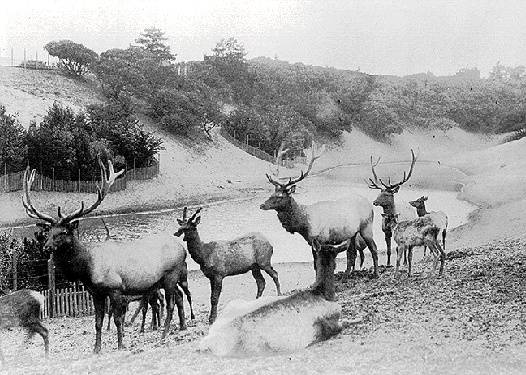

1899: deer meander through what is today the AIDS memorial grove between Middle Drive and Bowling Green Drive.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

When the idea of Golden Gate Park was first hatched, in the mid-1860's, the whole world scoffed: Everyone knew that the western half of San Francisco was an arid wasteland of barren sand dunes, upon which nothing could be made to grow. The Santa Rosa Press-Democrat, in 1873, wrote: "Of all the white elephants the city of San Francisco ever owned, they now own the largest in Golden Gate Park, a dreary waste of shifting sand hills where a blade of grass cannot be raised without four posts to keep it from blowing away..."

These soccer fields at the far western edge of Golden Gate Park were difficult to maintain as flat athletic fields covered in grass, due to problems with irrigation and soil drainage. So the Parks Department sponsored a ballot proposition that passed in 2013 that will convert these fields--not back to sand as one might assume would be appropriate, but to a type of artificial turf made from recycled tires!

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2014

The new recycled tire athletic fields, now brightly lit at night in ways that also disturb local bird life.

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2016

Fortunately, San Francisco ignored the conventional wisdom and set about the task of creating America's finest urban park. The two chief requirements were fertilizer and water; the latter was piped in and distributed with the help of the Dutch Windmill that still stands by the ocean near where John F. Kennedy Drive hits the Great Highway, while the former was provided in the form of the copious droppings generously bestowed upon the City's streets by the drays who were, until the 1920's, the mainstay of the local transportation system. Though no reliable estimate of the amount of horse-excrement collected for park fertilizer exists, the total undoubtedly ran into tens, even hundreds of thousands of tons.

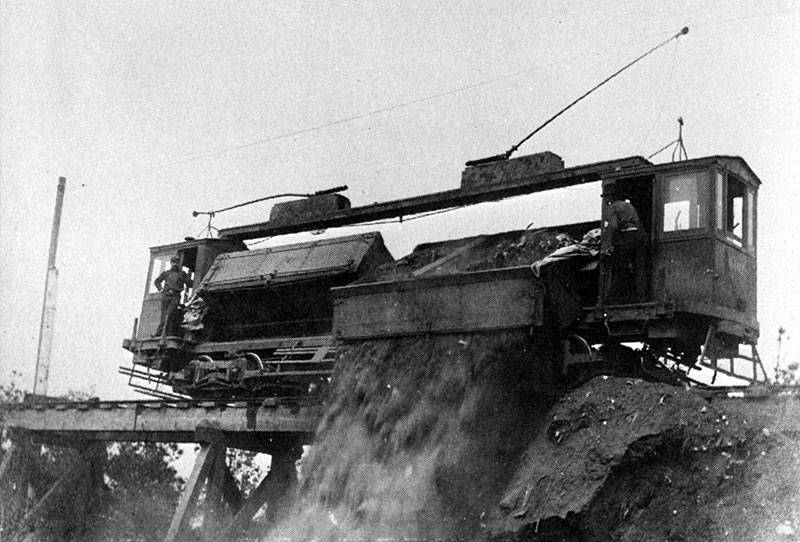

1905, dumping "street sweepings" (mostly horse manure) into a gully in Golden Gate Park.

Photo: United Railroads, via Charles Smallwood

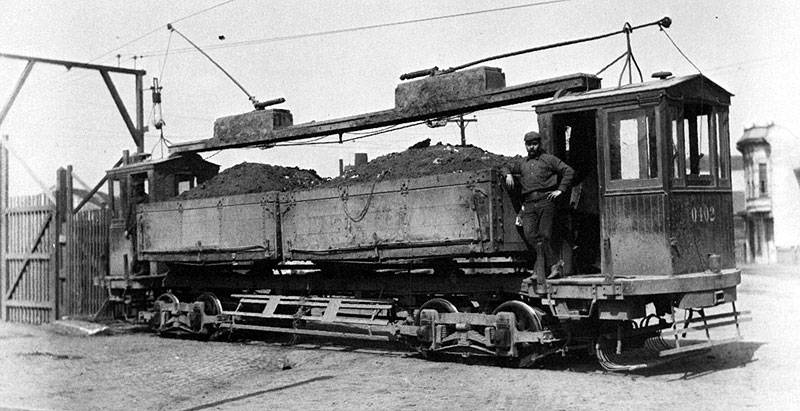

Street sweeping streetcar leaves the City Cleaning Department yard on Brannan between 7th and 8th Streets for Golden Gate Park with its "aromatic load."

Photo: United Railroads, via Charles Smallwood

In 1873 the Park Commission passed an ordinance prohibiting heavy wagons on park roads unless they had tires at least five inches wide. Street Department wagons were then turned away at the gates. In retaliation, the Street Department refused to let the park commissioners have any of the street sweepings, including horse manure, to fertilize the park. Not until the mid-1890s was this high-level dispute settled; after that, street railways were used to haul horse droppings and other sweepings to the park. Before that, the sweepings had been dumped into the Bay rather than used to improve the city park. (p. 17, Clary, Part 1 The Making of Golden Gate Park)

Despite its "natural" look, Golden Gate Park is a purely artificial paradise. One park gardener, asked to estimate how long the trees and plants would last if the irrigation were cut off, said "it'd be dunes again in ten or fifteen years ... though a few eucalyptus trees might survive." (And speaking of artificial paradises, Golden Gate Park has probably hosted more drug-induced mind-alterations per acre than any other patch of ground in the world.)

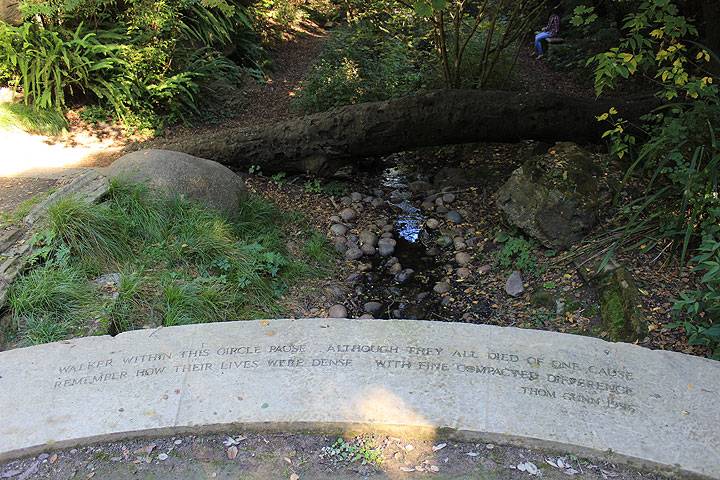

Entry to AIDS Memorial Grove in 2014, between Middle Drive and Bowling Green Drive.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Path through the AIDS Memorial Grove, 2014, where once sand dunes and fresh water ponds filled the landscape.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Mourners visit AIDS Memorial Grove, 1999

Photo: Rick Gerharter