Vesuvio Café: Difference between revisions

added Chuck Gould photo, fixed links |

added photo |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

'''Vesuvio's on Columbus Avenue''' | '''Vesuvio's on Columbus Avenue''' | ||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | |||

[[Image:Vesuvios 20190308 141735.jpg]] | |||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | ''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | ||

Latest revision as of 22:13, 23 April 2020

Historical Essay

By Robert Celli

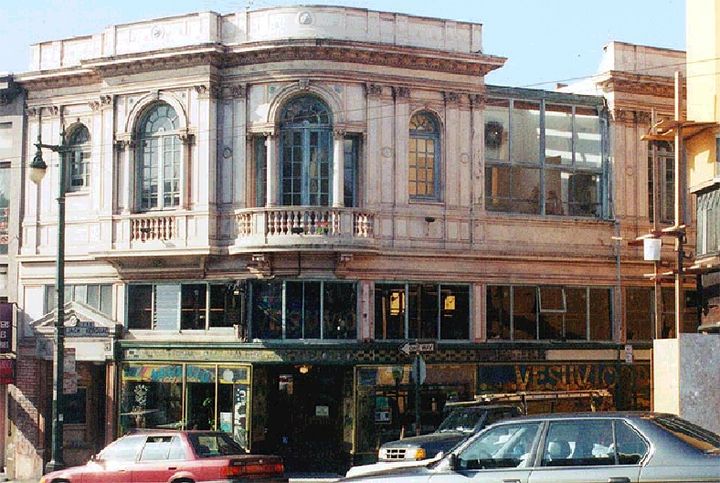

Vesuvio's on Columbus Avenue

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Photo: Chris Carlsson

At the peak of the Beat craze Henry Lenoir, proprietor of Vesuvio's and other North Beach drinking establishments placed a sign up in the window of his bar that said: 'Dont envy beatniks ... Be one!' For the benefit of the tourists and the wanna-be's, Lenoir sold a Beatnik Kit that included black-rimmed eyeglasses, a beret, a pair of sandals, a turtle-neck sweater (black), and a slip-on beard.

LIVING HISTORY, ONE DRINK AT A TIME OR 60 YEARS AND NO END IN SIGHT

Leo Riegler, part owner and “padrone” of Vesuvio Café on Columbus Avenue, once remarked, “You can’t be all things to all people.” While this is sage advice for most business owners, the truth is Vesuvio has been pretty much all things to the thousands that have called it home over the years.

“It’s the little boat that keeps cutting through the water.” That’s how managing partner and co-owner Janet Clyde describes the 60 year Vesuvio sojourn. The establishment continues to thrive when other neighborhood saloons have long since been wrecked, left to rot in the foggy ruins of San Francisco’s Barbary Coast,

Vesuvio has never been just a bar. It’s true that booze sales pay the bills but the place is also an art gallery, a museum, a living room for those of us in cramped apartments, a community meeting place, a support group headquarters, a literary Mecca, a mandatory stop on a tourist’s agenda, and a place to try and get laid. Upon pushing past the heavy wood door, beneath the faux stained glass bearing the saloon’s name, you enter a world of whimsy and time travel. I realize this might sound like romantic drivel, but I need to be excused. Vesuvio was my first San Francisco bar. And in this I’m not alone, “Vesuvio is everyone’s first bar in San Francisco,” says Clyde.

Perhaps the most sited reason for Vesuvio’s success was captured by Danny Brannigan, former bartender and longtime inhabitor, “Location, location, location.” As bar manager Mike Manson notes, pointing out the window toward the entrance of City Lights Bookstore, “These two places have a symbiotic relationship for people searching for that ‘Kerouac thing’. It’s one stop shopping.”

Lawrence Ferlinghetti opened his now venerable independent bookstore in 1954 and the two businesses have fed off each other ever since. At one point in the eighties, so the legend is told, Vesuvio was almost sold to a group that wanted to rename the bar Kerouac’s. Thankfully, this never came to pass. But as Manson points out, “Kerouac is the key; he helped to romanticize drinking and writing like Faulkner or Hemingway did a generation before him.”

The building that houses Vesuvio Cafe, 255 Columbus, is known as the Cavalli Building, former site of A. Cavalli & Co. bookstore. The structure dates back to 1913, with the second story added in 1918. Architect Italo Zanolini designed the structure in the Italian Renaissance Revival style. While not much is known about Zanolini, he was responsible for two of North Beach’s other architectural crown jewels, the Casa Fugazi (better known as Club Fugazi on Green near the corner of Powell) and the Venetian Gothic Bank at Columbus and Broadway, now home to the restaurant E Tutto Qua. The facade of the building is adorned with murals, created with loving care and considerable toil by resident house artist, the late Shawn O’Shaughnessy, who died in 1998. Stained glass pieces adorn the bow of the bar. On the rim of the entrance to the Café, just above the window looking out on Columbus Avenue, a scrawl reads, “We are itching to get away from Portland Oregon”.

Club Fugazi on Green Street, today the home of the long-running tourist favorite "Beach Blanket Babylon".

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The phrase originated from one of original owner Henri Lenoir’s antique postcards, which can still be seen on the screen directly above the bar-when the vintage turn of the century projector is turned on. It referenced a flea infestation that befell the city of Portland sometime at the end of the 19th century. The words captured Lenoir’s sense of whimsy and later seemed to embody the surreal use of language popularized by the Beats.

Lenoir opened Vesuvio in 1948. His vision was to create “a bohemian meeting place for artists to come to life.” A devout art lover, he filled the interior with his friend’s artwork. This is a tradition kept alive today by resident artist and curator Conrado Henriquez. Henriquez, who has been at Vesuvio since 1974, views his role as continuing the legacy of Lenoir and later O’Shaughnessy. Local artists still regularly show at Vesuvio.

The one most responsible for the look of Vesuvio is the aforementioned artist, Shawn O’Shaughnessy. Originally from Los Angeles and a veteran of the Korean War, he attended San Francisco’s Art Institute. Among his Vesuvio creations are the tabletops. These canvases, on which drinks are placed, often reveal the artist’s work under the magnification rendered by an empty glass.

O’Shaugnessy was also responsible for the tile effect that covers the interior walls and the bathrooms. This look was the result of a painstaking process O’Shaughnessy developed by lacquering and dyeing notebook paper used by the bartenders and cocktail waitresses. According to Clyde who witnessed O’Shaughnessy in action, it was not uncommon to go downstairs to use the bathroom and find the artist engaged in this tedious practice in the stall right next to you. This beautiful effect was also used to create the murals scattered about the bar. Long time morning bartender Josie Ramos has been dedicated to the restoration and preservation of O’Shaughnessy’s work.

The bar has only had a handful of owners over the last 60 years. Lenoir, a Swiss immigrant, remained at the helm until the late 80’s when the bar was sold to the Fein family who, along with partners Leo Riegler and Clyde—herself a thirty-year veteran of the café. There has been a conscious effort to stay true to the initial vision, providing a kind of balance that comes when the unemployed rub shoulders with downtown lawyers and bankers. Each bartender is allowed the freedom to exhibit his or her unique and considerable personality. It makes each visit special and different depending on who is walking the deck at that given time.

Vesuvio has a tidal quality that ebbs and flows throughout the course of the day. The day begins for Ramos when most are still sleeping, opening up the bar at 6am. Josie has been the morning bartender since 1989. “I guess I’ve always been drawn to the mornings,” she reflected, “I love to watch the sun come up.” She described the sensation of coming to set up the bar in the morning, “It’s as if the ghosts of the night before are still here.” The morning light filters through the stained glass and Tiffany lamps, hanging above the bar giving the place a peaceful serenity. The morning regulars assume their familiar spots at tables and stools, heads bowed over morning papers and chessboards.

What those not intimately connected with the bar may not know is how special the connection is between the bar and its regulars. Josie cooks food every Christmas, Easter, and Thanksgiving for those with nowhere to go. For many, Vesuvio is their family home. Clyde commissioned Ramos to construct “Day of the Dead” shadow boxes to honor those regulars that have passed. The boxes contain pictures, fruit, coins, cigarettes, and little bottles of booze that will hopefully help fortify the deceased in the afterlife.

A large cement slab fastened to the wall at the entrance end of the bar serves as another kind of memorial. This piece of concrete headstone memorializes those whose drinking careers at Vesuvio have been given a cease and desist order, an “86”.The slab is the handiwork of Leo Riegler who, one day in 1981, fervently carved into the wet cement in front of the establishment the names of the disinvited. The list contained the names of some celebrated writers like Gregory Corso and Bob Kaufman, a convicted murderess Janice Blue, and other North Beach denizens, no longer welcome inside.

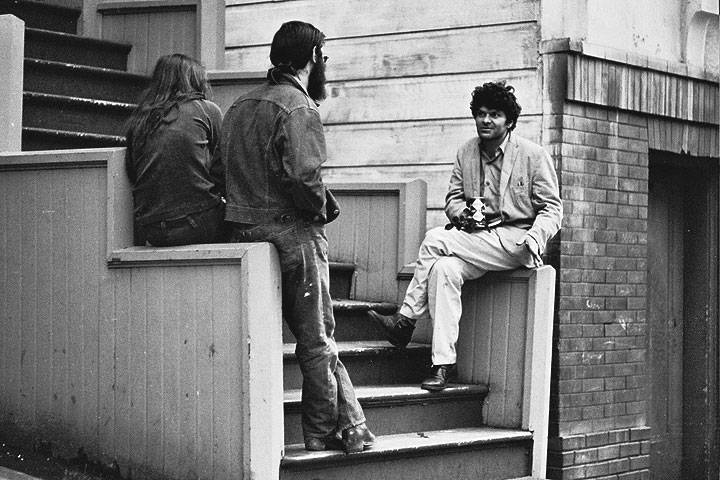

Gregory Corso, one of those expelled from Vesuvio's, hanging out with friends in the Haight-Ashbury, c. 1966.

Photo: © Chuck Gould, all rights reserved.

When the renovation of Jack Kerouac Alley was begun and the street was being dug up, Clyde rescued the etched 86 list. As recently as six months ago, Manson referenced the list, when a banished regular returned under the impression the statute of limitations had run out. In walked Dennis Crisp, after a twenty-year absence. He began again behaving in the fashion that had placed him on Riegler’s famed list. It took Manson a while to place the face, but when he realized who it was annoying everyone at the bar, he took Crisp’s drink from him.

“What are you doing?” Crisp asked

Manson responded ““You’re Dennis Crisp?”

“Yes”.

“You’re 86’d.”

Crisp was indignant, “That was twenty years ago!”

“Yes, but your name, it’s written in stone.” Manson said.

Vesuvio is part of a special triumvirate of bars that includes two watering holes on other side of Columbus: Spec's — (that Lenoir managed in the 1940s) and Tosca Café. The three form a Bermuda triangle of sorts, where those that navigate between them, often find their memory of the night before has disappeared without a trace. The regulars call these excursions “North Beach roulette.” One jaywalking voyager flatly states “You will get hit by a car at some point, some people more often than others.”

It’s these stories that make Vesuvio the treasure that it has been for the past 60 years. The connection to the Beat era, the movie stars, writers, and other notables that have walked through its door, while exciting, isn’t going to sustain a bar. Rather it’s the “history of stories,” the devotion of the regulars, and the respect and care the staff take to preserve the integrity of Henri Lenoir’s initial vision. He wanted to create a “gathering place for the people of North Beach”. In the process it became a gathering place for people from all over the world.

The tourists will continue to make Vesuvio a thriving draw. It routinely ranks as one of America’s top bars. Young men and women, fortified with the poetry of the Beats will walk the well worn path beneath the scrawl reading, “Itching to get away from Portland Oregon.” After all, we all have a bit of “Portland” we are trying to get away from, and as long as that is true, folks of every stripe will find a safe harbor at the Vesuvio Café.

Originally published in The Semaphore, issue 186, Winter 2009, a publication of the Telegraph Hill Dwellers Association.