Pre-Incarceration Japanese Experience: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' ''by Rafael Esteves, 2019'' {| style="color: black; background-color:...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

“NJAHS Statement on Incarceration ‘Precedent’ - National Japanese American Historical Society.” NJAHS, 21 Dec. 2016, www.njahs.org/njahs-statement-incarceration-precedent/. | “NJAHS Statement on Incarceration ‘Precedent’ - National Japanese American Historical Society.” NJAHS, 21 Dec. 2016, www.njahs.org/njahs-statement-incarceration-precedent/. | ||

[[category:Japanese]] [[category:Racism]] [[category:WWII]] [[category:Military]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:Western Addition]] [[category:East Bay]] | |||

Revision as of 14:08, 18 July 2019

Historical Essay

by Rafael Esteves, 2019

| Why did the United States decided to place the Japanese and Japanese Americans in concentration camps? The public perception of Japanese people worsened in the months after the United States entering World War II, spread by members of the media and government. Eventually, anti-Japanese sentiment became so prominent that the army incarcerated the Japanese and Japanese Americans living on the west coast. |

A group of public elementary school students say the pledge of allegiance. The Japanese Americans among them were sent to concentration camps with their families.

Photo: Dorothea Lange

It is often assumed that the attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent beginning of World War II lead to the immediate incarceration of the Japanese Americans on the west coast. However, the four-month interval between Pearl Harbor and the placement of Japanese Americans in concentration camps highlights the reality of the Japanese American experience post WWII. A paper published by Tamotsu Shibutani, a Japanese American studying at the University of California, Berkeley in 1942, details a first-hand account of how the Japanese were treated leading up to their incarceration.

Two days following Pearl Harbor, United States Attorney General Francis Biddle explained that, “There are in the United States many persons of Japanese extraction whose loyalty to this country, even in the present emergency, is unquestioned. It would therefore be a serious mistake to take any action against these people” (Shibutani 59). The sentiment expressed by Biddle was also reflected in the government’s treatment of Japanese immigrants. Surprisingly, in the immediate weeks following December 7th there were far fewer discriminatory actions taken by the government, when compared to the months following the incident. Immediately following the Pearl Harbor attacks, an estimated 11,000 immigrants from the Axis countries, of which 8,000 were Japanese, were put on trial for being suspected as national security threats. Immigrants suspected of aiding their home countries were given individual trials but many were found innocent and released (Shibutani 58, Daniels 300). Outside of these arrests, the government took few actions against any immigrants for the first few weeks after it entered the war.

On December 27th the federal government issued the first order that affected Japanese immigrants; all immigrants from Axis countries, to be referred as “enemy aliens,” were required to turn in their radios, cameras, and firearms for the duration of the war (Shibutani 60). In late December, Attorney General Biddle authorized the warrantless search of any home where an enemy alien resided (Daniels 304). Soon after, on January 1st, a travel ban was put in place for all enemy aliens which prevented them from leaving the neighborhood in which they resided, except for work (Shibutani 60). Despite these regulations, public opinion favored treating the Japanese fairly until mid-January (Shibutani 64).

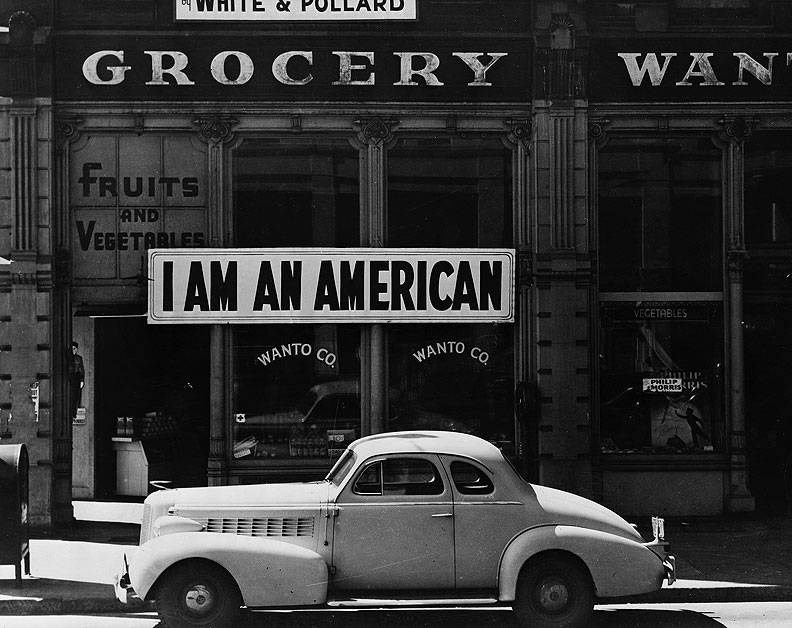

Japanese American store owner in Oakland displays his loyalty to the United States.

Photo: Dorothea Lange

However, by the end of January, people’s attitudes towards the Japanese began to change as local government officials and newspapers, fueled by US losses in the war abroad, began to spread fear (Daniels 302, Shibutani 65). As the government continued its arrests that it had been conducting since Pearl Harbor, the media began increasing its coverage of these raids and blowing them out of proportion. The media published articles titled “FBI Seizes 21 Axis Aliens in Vallejo Spy Ring Hunt,” “All-Out Alien Roundup On,” and “Mass Raids Trap Scores In Coast’s Greatest Spy Hunt.” (Shibutani 68) An example of such media outrage can be found in their reaction to arrests made in Sacramento. The media explained that Japanese men were arrested for possessing a directory of all Japanese in the United States, Japanese army uniforms, and serial bomb casings. However, the media failed to explain that such a directory was published in Japanese newspapers, Japan’s mandatory military service meant that all Japanese men would own a uniform, and that the bomb casings were used for theatrical purposes (Shibutani 68).

One of the first instances of discrimination towards American citizens of Japanese descent occurred on January 16th when a proposal to prevent Japanese-American individuals from working in the state government reached the California State Senate. On January 28th, the Los Angeles County Supervisors requested that the federal government forcibly remove Japanese immigrants from the coast; two days later, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors made the same request (Shibutani 67). Another example of local governments spreading anti-Japanese sentiment can be seen from the January 27th decision of the California State Personnel Board to not hire any more Japanese Americans and allow supervisors to investigate their Japanese American employees. (Shibutani 76)

The dramatic change in the treatment of Japanese immigrants through these months can be seen through the differences between the November and January editions of a Japanese newspaper, Current Life. In the November edition, most of the articles indicated that life for the Japanese was normal. Although one article entitled “How Loyal Are Our Japanese American Citizens” discussed the fear that some Americans had that Japanese and Japanese Americans were loyal to Japan, no other article in the November publication mentioned discrimination against the Japanese. The January edition is remarkably different, a selection of articles included “A Racial War?,” “Are the Nisei Being Discriminated Against in the Red Cross Volunteer Service?,” and “A Plea for Tolerance.”

Surprisingly, many Japanese and Japanese Americans continued to have faith in the American government throughout this process. One article in the December 1941 publication of Current Life titled “God Bless America” described how one Japanese American woman felt about the United States. This woman was forced to move to Japan because of a pre-arranged marriage but when she broke off the engagement she was eager to return to her home of Hawaii:

“When I stepped on American soil in Hawaii, there were tears in my eyes. I wanted to stoop down and kiss the ground on which I walked. The sound of the English language, the smiling happy faces on the street, the noise and bustling confusion of the Honolulu business district, all went to my head like rare wine.”

Another article in the January edition of Current Life discussed the first time Japanese incarceration was proposed, “One of the most ludicrous schemes aimed to alleviate the potential fifth column menace on the Pacific Coast has been proposed. Patriotic native-born Japanese residents of the United States should submit themselves to confinement in concentration camps.” In fact, Current Life editors believed incarceration was such a ridiculous idea that this was the shortest article of the newspaper, consisting of only three sentences. Even more remarkably, the Japanese American Citizens League encouraged the Japanese to comply with the government’s forced removal and opposed the Japanese who did fight against the racism they were experiencing. The support for the government was not only present in the Japanese leadership, most Japanese complied with the government as they still had faith they would be treated fairly (Daniels 303). Neither the public nor the government compelled by the Japanese Americans’ loyalty.

Eventually anti-Japanese beliefs became so prominent that the federal government felt compelled to take action. On February 20th, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which allowed the military to ban anyone deemed a danger from a broad swath of the western United States. As late as February 25th, the government continued assuring the public that there would not be a mass incarceration of the Japanese. Despite these assurances, on March 1st the Army announced the west coast as a military zone. Throughout the month, the army forcibly removed Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans from certain areas; however, those forcibly removed during this stage were not incarcerated. This culminated on March 22nd when the U.S. Army began to incarcerate the Japanese and their families.

The first group of Japanese and Japanese Americans leave for concentration camps.

Photo: Dorothea Lange

It remains incredibly important for the United States to acknowledge and learn from its previous mistakes in history in order to avoid making them again. This particular tragedy is of vital importance given the anti-immigrant sentiment that has been growing in the United States. As President Donald Trump ran his campaign in 2016, Carl Higbie, a spokesman for a pro-Trump super PAC, claimed that the Japanese incarceration during World War II could serve as precedent for President Trump’s plan to create a Muslim registry. As Shibutani compares the way the Germans were treated during World War I to how the Japanese were treated during World War II, he notes that “Perhaps history does not repeat itself, yet we are forced at times to stare at glaring parallels” (56).

Sources

Current Life: The Magazine for the American Born Japanese. San Francisco, 1940-1942. Print.

Loberg, Erica. “Japanese Internment in San Francisco.” FoundSF, www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Japanese_Internment_in_San_Francisco

Shibutani, Tamotsu. The Initial Impact of the War on the Japanese Communities in the San Francisco Bay Region: A Preliminary Report. Berkeley, Calif: University of California, 1942. Print.

“It's Time to Retire WWII-Era Euphemisms for Japanese American Incarceration - Densho: Japanese American Incarceration and Japanese Internment.” Densho, 26 Apr. 2019, https://densho.org/time-to-retire-euphemisms-for-japanese-american-incarceration/

“Japanese Internment.” FoundSF, Northern California Coalition on Immigrant Rights, www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Japanese_Internment

“NJAHS Statement on Incarceration ‘Precedent’ - National Japanese American Historical Society.” NJAHS, 21 Dec. 2016, www.njahs.org/njahs-statement-incarceration-precedent/.