Livermore Women's Peace Camp: Difference between revisions

(added to anti-nuke tour) |

(added abstract) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

''by Barbara Haber, originally published in "It's About Times," the Abalone Alliance newspaper, February-March 1984'' | ''by Barbara Haber, originally published in "It's About Times," the Abalone Alliance newspaper, February-March 1984'' | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" |'''Livermore Peace Lab was a nonviolent anti-nuclear protest which took place at Lawrence Livermore Labs during the 1980s. In this first-hand account, Barbara Haber describes her experience as media spokesperson, the reaction by the local media, and places the project in the context of a broader global endeavor. In doing so, she shares both her doubts and her hopes regarding the project’s potential for success.''' | |||

|} | |||

Forgive the romantic beginning. It is Saturday, the first day of construction at the new peace camp in Livermore, nearly sunset. I am walking across the big field on which the encampment is set, alone, performing some small but necessary errand. The dwindling light makes the surrounding hills look flat and velvety, bringing out the sensuality of their contours. The cars hum by on the freeway, headlights sparkling. The air smells good and I suddenly notice I am happy. I trudge along, trying to avoid the holes arid the cow shit, toward the sound of hammering and laughter. A small group of people is putting in the last supports behind the big sign facing the freeway. "Livermore Peace Lab," it says. | Forgive the romantic beginning. It is Saturday, the first day of construction at the new peace camp in Livermore, nearly sunset. I am walking across the big field on which the encampment is set, alone, performing some small but necessary errand. The dwindling light makes the surrounding hills look flat and velvety, bringing out the sensuality of their contours. The cars hum by on the freeway, headlights sparkling. The air smells good and I suddenly notice I am happy. I trudge along, trying to avoid the holes arid the cow shit, toward the sound of hammering and laughter. A small group of people is putting in the last supports behind the big sign facing the freeway. "Livermore Peace Lab," it says. | ||

Revision as of 14:30, 15 May 2019

"I was there..."

by Barbara Haber, originally published in "It's About Times," the Abalone Alliance newspaper, February-March 1984

| Livermore Peace Lab was a nonviolent anti-nuclear protest which took place at Lawrence Livermore Labs during the 1980s. In this first-hand account, Barbara Haber describes her experience as media spokesperson, the reaction by the local media, and places the project in the context of a broader global endeavor. In doing so, she shares both her doubts and her hopes regarding the project’s potential for success. |

Forgive the romantic beginning. It is Saturday, the first day of construction at the new peace camp in Livermore, nearly sunset. I am walking across the big field on which the encampment is set, alone, performing some small but necessary errand. The dwindling light makes the surrounding hills look flat and velvety, bringing out the sensuality of their contours. The cars hum by on the freeway, headlights sparkling. The air smells good and I suddenly notice I am happy. I trudge along, trying to avoid the holes arid the cow shit, toward the sound of hammering and laughter. A small group of people is putting in the last supports behind the big sign facing the freeway. "Livermore Peace Lab," it says.

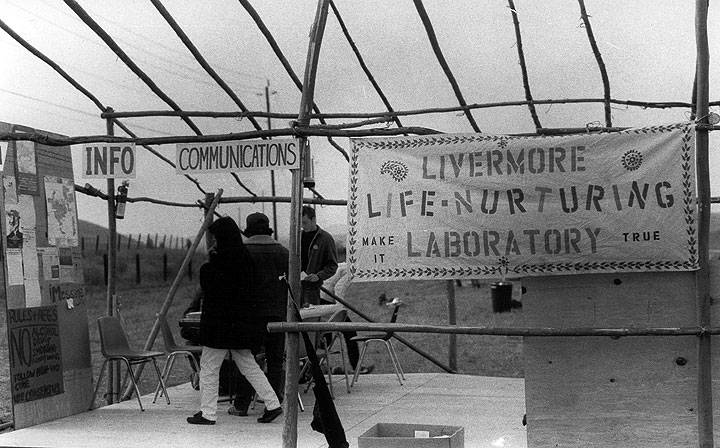

Life Nurturing Laboratory at protest camp in front of Lawrence Livermore Labs, 1984.

Photo: It's About Times newspaper

The sign is flanked by ropes hung with red and white and green banners that wave buoyantly in the wind. The sign is the latest artistic creation of Mark, who has also given us the Grim Reaper, that now familiar giant that stalks most peace movement actions. Osha, Sharon, Tad, Fern and Patrick are helping Mark secure it, worrying that the strong winds will blow it over in the night.

The material for, the banners was bought in town this morning by Michael, a bargain at 79 cents a yard. He and others .have cut the material and sewn it to the ropes, sitting in the sunlight here at the camp. Then the holes have been dug, the ropes attached to the stakes, the stakes driven into the holes. It is an afternoon's work for several people.

Some of these people are my friends. Others not. I have known most of them a year and a half, as long as I've been in LAG. I've had good fights with most of them, and some sweet moments too, when what we share has broken through the squabbles of political work. The word "comrade" flits into my mind as I walk toward the group by the sign. The sound of it sends a ripple of warmth through my body.

Having done my errand l am soon heading back across the field to the center of the encampment. The smells of supper and the clang of dishes pour out of the corrugated metal cooking shack. The phones at the information center ring. Voices answer. Off to the left people are digging a long trench to carry kitchen waste water. To the right a dozen or so multi-colored tents are huddled together. In the twilight the campers move about doing their work, talking and laughing with each other.

None of this was here this morning. People made it with their hands, therefore it exists. A definitely funky, makeshift, low- budget operation.

I have my doubts about this peace camp: will people show up, will-they do anything worth doing, will they have any effect? But as I sit quietly waiting for my ride back to the city, I am not thinking about that. I am, for a moment, transported out of the present, into a future I will probably never live out. I am feeling what it might be like to live in a human-scale cooperative community, geared toward production rather than consumption, peace rather than war. I smile to myself, embarrassed at the romanticism of my thoughts. But at the same time I know that I am getting the point, at least one point, of this peculiar creation. The camp is a kind of living theater in which even an old, jaded political activist like me can suspend, briefly, my disbelief in the possible. As I sit I am remembering the vision that binds our frenetic political activity together. I can feel the relief and joyfulness of shared purpose and shared labor.

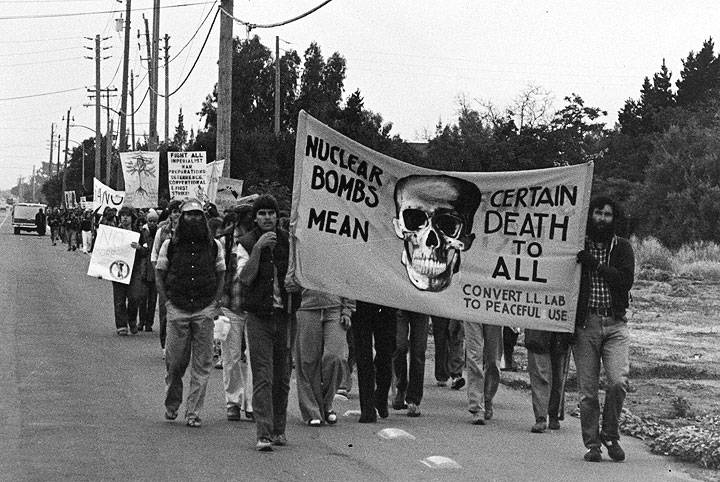

Lawrence Livermore Labs anti-nuclear protest on perimeter.

Photo: It's About Times newspaper

If the Livermore Peace Laboratory is a flight into a visionary future, it is also part of a grand old tradition, one that goes back at least two whole years. That was when the first peace camp, the all-women encampment at Greenham Common in England, was begun. The women are still there, squatting on the tail of the Air Force base where the newly imported cruise missiles are stored. They are embarrassing the hell out of the British government, harassing the US military with theatre, leafletting and civil disobedience, making it impossible to transport the damned missiles on trucks to scattered locations in the countryside from which they would be launched. The women at Greenham have virtually imprisoned the missiles. And by their ornery perseverance they have made themselves the moral center of the British peace movement.

Once upon a time there was no such thing as a peace camp. Someone thought the idea up, and then people who liked the idea made it happen, and It became a real thing in the world, a part of movement history and legend and inspiration. It is clearly a beautiful idea, rich in possibility for innovation, connection among people, and a bother to the powers-that-be.

And other people, hearing about Greenham Common, have made other peace camps in other places: five more in England, three in Scotland, eleven in Germany, two at Comiso, one in Australia, one in Canada, and in this country at Seneca Falls, Tucson, Puget Sound, Silicon Valley and now Livermore. First there was none, then one, then many. When we act something is born. Our acts move others. Sometimes, not always. When we begin we do not know the destiny of our creations. So it is with all works of art and love.

Sunday. Official opening day. Two hundred people stand in a circle. A ceremony blessing the land is led by several native American activists. At the end people' move around the circle shaking hands and making eye contact with each person in the circle. Later there is music and poetry and food. The donor of the property, Harold Meford, is there. He is a lawyer, in his late sixties, dressed in a suit, shaking lots of hands, beaming with pleasure.

The media arrive with hard questions. What will, the camp accomplish? How will it affect what. goes on at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory? How many will participate? Do we really expect people from the town and the Lab to show up? Will' we just be talking to ourselves?

I feel uncomfortable in my role as media spoke. How do I know the answers? I have had nothing to do with organizing this camp. But even those who have don't seem to know what will happen. The critic in me says that's what's wrong with the whole idea: you plop yourselves down in the middle of the field; you call the media and demand attention; and you really don't have the slightest idea who's committed, who will show up, what they will do. Not only that, it's January and sooner or later it's bound to rain and chase people away. And here I am, trying to make the camp sound more together than it really is, stating my hopes as though they were our collective, well worked out plans.

I say that we plan to go to the Lab and to the town to talk with people, to invite them to the camp. I say that our presence calls attention to the Lab's war work. I tell my favorite story, about the ex-Lab employee who sent a message to LAG saying, “Keep it up, you really do disturb the minds of the workers."

The reporters want to know if we plan civil disobedience. I tell them no, that this is meant to be a non-confrontational experiment in communication. In my heart I wonder if the camp can muster any energy without the fuel of confrontation. The more I talk, the more my doubts come to the surface. By the end of the afternoon I notice I am feeling slightly depressed, and maybe a little sleazy too.

It is Monday, the day after the camp opening. I have returned to my desk, to my role as journalist. I call the, camp to get the facts, ma'am. Like all the other journalists I want to know what kind of organizing IS really going on, what kind of impact it's having. I feel it's only fair to point out the camp's weaknesses in my article so we can learn from them.

The answers surprise me. In two and a half days of the camp's existence at least six Lab employees have visited. One, a scientist at the Lab for 29 years, has sat by the campfire for three hours, sharing his concerns for the future. A younger scientist has come on his lunch hour with suggestions about how to pressure the Lab.

Non-employees from the town have come too, over a dozen of them. Several have asked for tasks; one has invited the campers to his church next Sunday. The next night he is back, inviting them to his house to catch themselves on Channels 2, 5, and 40. A young couple from the horse ranch up the road have come to talk about their fears. They are 19 or 20 years old, about to be married, worried about the possibility of war in the future, poison in the present. Meanwhile the campers have leafleted at the Lab cafeteria, and are planning to leaflet in Livermore.

The media have kept coming too. Everyone is surprised at the amount of coverage: all the Bay Area newspapers, the Valley papers, the San Jose Mercury News. KRON announces its intention to spend 24 hours at the camp. Izvestia features it. A reporter from the Tribune calls one of the organizers, annoyed that he was not specially informed about this story.

The woman who is telling me all this, Alexandra, my media co-worker of yesterday, is excited as she talks. "It's happening," she says. "It’s really happening." But then Tom, one of the main organizers, comes on the phone, tired and worried. “We need more people,” he tells me, “to leaflet, to answer the phones, to talk to media and townspeople when they visit. And we could use an electrician and a couple of carpenters too." Tom has to leave the camp for a few days to return to his job. He is pleading for help in keeping alive this experiment he has worked so hard to create.

I hang up, my skepticism banished by excitement. I'm feeling a personal stake in the whole business, really for the first time. Until now it's been other people who were making it happen, whose efforts would fail or succeed. I might offer a bit of help here or there, but basically I have been the outsider, the witness, the critic, the appreciator.

Now lam feeling as though that piece of land is mine, too. I decide to postpone being a journalist until evening. First I must call people, everyone I know who's part of an affinity group, or organization that might spend a day or a few hours at the camp. Then I must figure out how to juggle my own schedule.

I want to be part of this creation, and suddenly that future I said I would never live out feels as though it is here, now, for the taking. I am grateful to those comrades, less doubting than I, who had the vision to risk it.