Sculptor Douglas Tilden Was California’s Finest: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' ''by Ken Stein'' ''The following article first appeared in the ''Ber...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

[[category:Public Art]] [[category:Famous characters]] [[category:East Bay]] [[category:1890s]] [[category:Golden Gate Park]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1900s]] [[category:1910s]] [[category:Monuments]] | [[category:Public Art]] [[category:Famous characters]] [[category:East Bay]] [[category:1890s]] [[category:Golden Gate Park]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1900s]] [[category:1910s]] [[category:Monuments]] [[category:sports]] | ||

Revision as of 15:45, 28 January 2019

Historical Essay

by Ken Stein

The following article first appeared in the Berkeley Gazette, 2/10/80, later reprinted in "Exactly Opposite the Golden Gate," Berkeley Historical Society, 1983 & 1986.

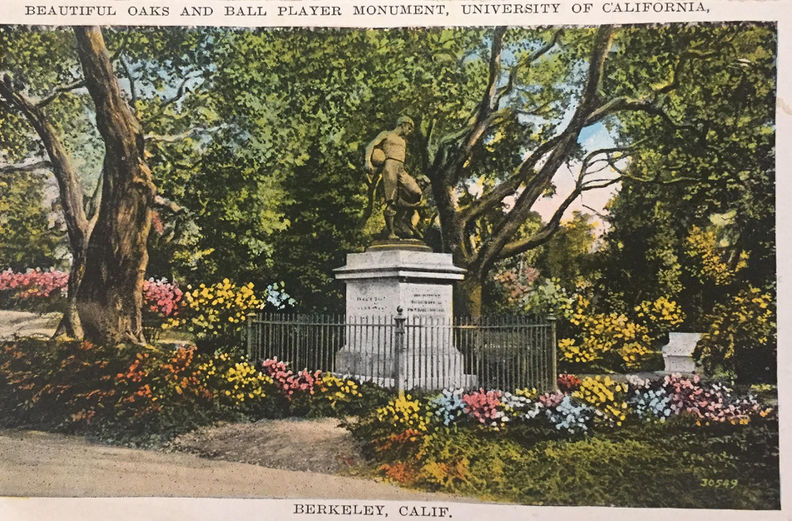

The Football Players, sculpture by Douglas Tilden, on UC Berkeley campus.

Postcard: courtesy Ken Stein

Douglas Tilden's statue of "The Football Players" was dedicated on the UC-Berkeley campus at 11:45 A.M. on Class Day, May 10, 1900. The statue was in fact a prize, presented to the university by San Francisco Mayor James Phelan (later Senator Phelan) for having won a contest which Phelan himself had devised.

Whichever football team won the Big Game two years in a row would win the statue. And UC won, handily defeating Stanford, first in 1898 (22-0) and again in 1899 (30-0). Since the start of the Big Game tradition in 1891, although Cal had tied three games, it had never beaten its rival prior to the Phelan contest. The two victories were attributed in large measure to the efforts of Cal's new coach, Gary Cochran, "a young man of marvelous skill in football and a great leader among students."

In Brick Morse's chronicle of the 1899 Big Game we learn that, "With Pringle and Whipple tearing holes ahead of them, the California backs went through for gain after gain until 24 points had been rolled up in the first half. Chet Murphy, one of the two Stanford veterans, tried to stop the whole California team, single-handed, but was finally forced out of the game with a couple of broken ribs. It was the finish of a great and worthy opponent, and the California rooters stood up and cheered him as he limped from the field. That meant something in those days of intense rivalry. Neither California nor Stanford ever gave meaningless cheers for a fallen enemy."

And so Cal won itself a statue. It is a statue of heroic strength and dignity, and of an equally heroic compassion and tenderness—attributes of the period, and perhaps even more, of the sculptor himself.

Tilden's family was prominent in California's early history. His grandfather Adna Hecox and Hecox's young daughter Catherine (later to be Tilden's mother), crossed the plains with the ill-fated Donner Party in 1846, "but separated from them before the catastrophe in the mountains." Hecox was the last alcalde (Spanish mayor) of Santa Cruz under the Mexican Government, and Tilden's father, Dr. W. F. Tilden, was twice a member of the state Legislature.

Unquestionably one of California's finest sculptors, Douglas Tilden was born in Chico in 1860. (He is no relation to Charles Lee Tilden, after whom Tilden Park was named). As a young child, Tilden lost his hearing due to scarlet fever, and he entered the California School for the Deaf and Blind in Berkeley in 1866.

Coincidently, Tilden's birth date (May 1, 1860) was also the day that the California Schools for the Deaf and Blind (at that time called the Deaf and Dumb and Blind Asylum) first opened its doors in San Francisco. A legislative act of March 31, 1866, provided for a commission to select a new site. The School for the Deaf and Blind, Berkeley's first state institution, laid the foundation for its new building in Berkeley in 1867 six years before the coming of the University of California.

In light of the 20th century controversy [read UC Berkeley land-grab] surrounding the relocation of the schools to Fremont in 1980, it is worth nothing that the 1866 commission took great pains to ensure that the location should not be "in the heart of a big city, nor in the remote country, but rather in a suburban locality within reach of the social and economic advantages of a well-established community." As pointed out by Berkeley historian William Ferrier, "Their judgment was that the site to be chosen should be, if possible, in the vicinity of other educational institutions and where there was a population likely to cherish such an institution."

The California Schools for the Deaf and Blind were cherished in Berkeley until 1980, when they were forced to move to Fremont by the University and State of California, which had had their eyes on the site since at least the 1940s. The University renamed the site the Dwight-Derby Clark Kerr Campus and converted it to student housing.

Tilden graduated from the school in 1879, and had intended to enter the University of California to prepare for a literary career. However, he ended up, instead, accepting a position teaching at the Deaf School, where he remained for 8 years. During this time, he contributed numerous articles to California magazines on the subject of deafness.

Tilden discovered sculpture when he was 23. Prior to that time, wrote Tilden, "I knew nothing about sculpture." After that, he continued to teach at the school for four years, studying sculpture in his spare time. The trustees of the school were so impressed by his self-taught early work that they provided him with a scholarship to further his studies in New York and Paris. In Paris, he studied for a year under the great sculptor Paul Chopin, who was also deaf.

The Bear Hunt, in its current location at the California School for the Deaf in Fremont.

Photo: courtesy Ken Stein

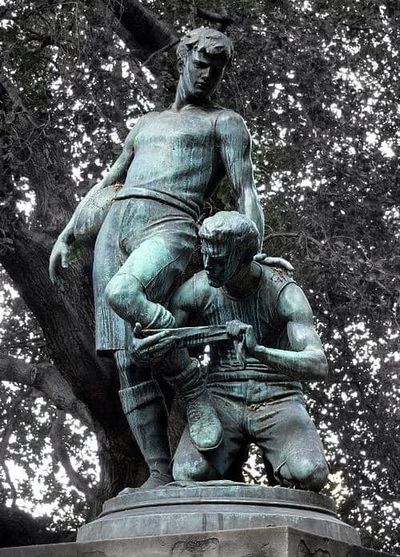

Tilden's first work in Paris, the "Ball Player," won immediate acceptance at the famed Salon. The work is now in Golden Gate Park, as are his statues of "Father Junipero Serra" and "California Volunteers." Tilden's "The Football Players" was completed in Paris in 1893, where it won a medal at the Paris Exposition.

In 1894 Tilden returned to San Francisco, where he taught sculpture at UC's Mark Hopkins Institute of Art. Communication with his students was accomplished "with a pad, paper, and pencil, that he always carried with him."

Tilden's work for and with the deaf was a lifelong and vital concern. While in Paris, he inaugurated the first International Congress of the Deaf, of which he became vice-president, and he was a member of the program committee of the second International Congress held under the auspices of the World's Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1893, where he also served on the "jury" judging sculpture at the exposition itself.

In 1896, Tilden married Elizabeth Delano Cole, "a ravishing beauty," and moved his studio to Oakland, where for many years he continued to create a number of outstanding public statues and monuments. His most well-known works include the "Mechanics Statue" and the "Native Sons" fountains on Market Street in S.F., "The Bear Hunt," on the grounds of his Alma Mater now in Fremont, and "U.S. Senator Stephen M. White," in Los Angeles. It was Tilden who first suggested that sculptural art be used to beautify Golden Gate Park.

During Tilden's days of affluence and renown, his greatest patron had been Sen. James Phelan. According to a biography of Tilden included in a 1960 history of the California School for the Deaf, Tilden, "genius that he was, regarded competition beneath him and would not submit entries in competition with others. This resulted in a breach between Tilden and Phelan which gradually widened and proved to be catastrophic for Tilden. His commissions dwindled."

Around 1915, (when he was 55) Tilden suffered from what he termed "a spell of inertia." He laid aside his chisel and mallet and lost all interest in his art. He worked for a manufacturing concern in the East Bay until 1925, when he began work on "The Bridge," which has been called " a poem in bronze." It is considered by some to be the artist's best work. (A small model is in the collection at the Oakland Museum).

In 1926, he was divorced by his wife and thereafter "lived the life of a recluse, being rather embittered against the whole world."

As a companion to "The Bridge," Tilden had planned a frieze for the 1939 San Francisco Exposition, and although "he strove night and day to finish what he regarded as his masterpiece," it was a work he would not live to complete.

The California School for the Deaf biography concludes by saying that "his last days were not happy ones," and goes on to cite the following from a Digest of the Deaf article that appeared in 1940: "Estranged from his wife, patrons, and friends, embittered by the failure of his dreams for an artistic and educational Utopia on the West Coast, and in straightened circumstances, the unhappy, proud, and lonely old man was found dead in his studio from heart failure on Aug. 6, 1935."

At the time, Tilden's home and studio were at 834 Channing Way in Berkeley, where he had moved in the late 1920s. The day after Tilden's death, the Berkeley Gazette reported of neighbors telling how "at one time he came to borrow water and it was discovered that his water and lights had been shut off because he had no money to pay for them. For several nights he had been using candles and cooking on a small oil stove. Friends secured for him a state old age pension of $35 a month. He seemed indignant and hastily wrote on a piece of paper, I'm no pauper.' Later it was learned that he had not eaten for several days."

In the end then, there were no California rooters to stand up and cheer for Douglas Tilden "as he limped from the field." He was buried in Mountain View Cemetery, and his funeral services were conducted in sign language.

Douglas Tilden has always been one of my life heroes. I wrote this article 40 years ago. What I found out years later is that part of the reason that Tilden was destitute in his later years was that the California School for the Deaf (CSD) in Berkeley (where he had gone to school and originally taught art) refused to re-hire him. They and other Deaf Schools around the country refused to hire any Deaf teachers subsequent to the big International Conference Of Deaf Educators in Milan in the1890s, where it was decided that not only would sign language be banned, but that Deaf people would not be allowed to teach in Deaf Schools; and that that oralism would be the way things would be thenceforth. No deaf people were allowed participation in that conference). Those policies stayed in place until the 1960s.

Joanne Jauragui, who I worked with at Berkeley’s Center For Independent Living in the mid-1970a once told me about how when she was a little girl at a Deaf School in New York, her hands would be slapped whenever she was caught using sign language; and how frustrating it was for her, that when all of her hearing peers in the public schools were spending all of their time on academics, that she would have to spend hours every day practicing vocalizing. . . ah . . . oh . . . ooh . . . eeeee.

– Ken Stein, Berkeley, February 2019