HOMEY Mural 24th and Capp: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(added photo) |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

''Photos: Chris Carlsson'' | ''Photos: Chris Carlsson'' | ||

[[Image:House-of-Brakes-repainted 20141205 155358.jpg]] | |||

'''After repainting in 2014.''' | |||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | |||

[[Balmy Alley: a Modernist Approach|Prev. Document]] [[Joel Bergner|Next Document]] | [[Balmy Alley: a Modernist Approach|Prev. Document]] [[Joel Bergner|Next Document]] | ||

[[category:Public Art]] [[category:Mission]] [[category:2000s]] [[category:Latino]] [[category:murals]] [[category:Jewish]] | [[category:Public Art]] [[category:Mission]] [[category:2000s]] [[category:Latino]] [[category:murals]] [[category:Jewish]] [[category:2010s]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:05, 12 September 2018

Historical Essay

by Amanda Maria Morrison

This is excerpted from an article that originally appeared in the San Francisco Bay Guardian, Nov. 28-Dec. 4 2007 issue

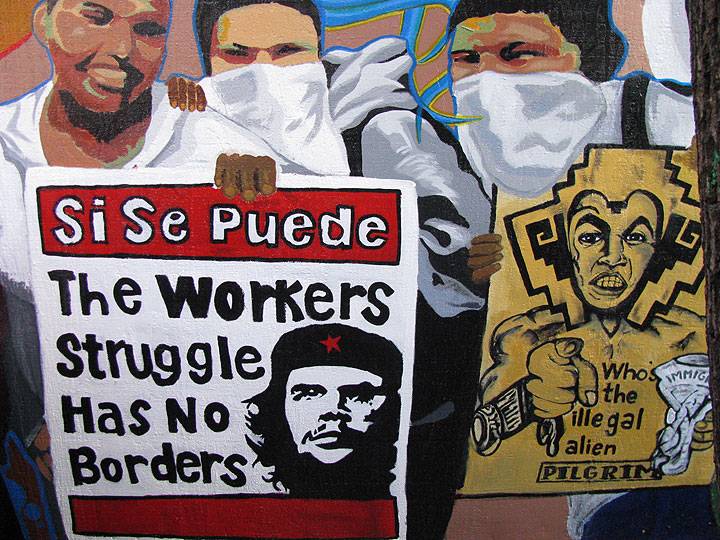

Craftily melding urban motifs, the mural celebrates [Latino youth]’s bicultural realities: lowriders cruise alongside hyphy “scrapers,” pachucos and Mac Dre mingle, and graffiti lettering makes the same statement as silk-screened Brown Pride posters of the 1970s.

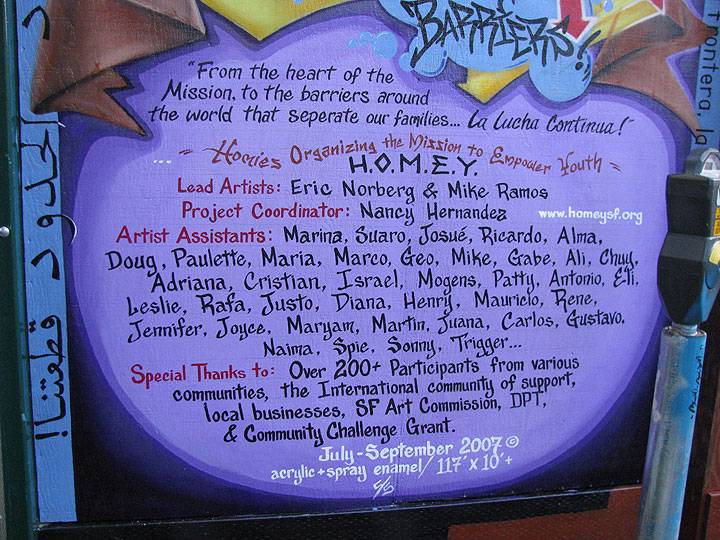

The work was created from July to September, 2007 by members of Organizing the Mission to Empower Youth, a neighborhood-based youth leadership nonprofit serving at-risk Latino teens and young adults. The primary goal of HOMEY is violence prevention. Through art, education, and skill-building activities, the organization offers alternatives to young people growing up in a rough environment where gangbanging, drug dealing, gun violence, and incarceration are the norm. . .

Although a core group of teen and adult artists executed the initial planning and design for the mural, in the end more than 200 community members contributed to the painting.

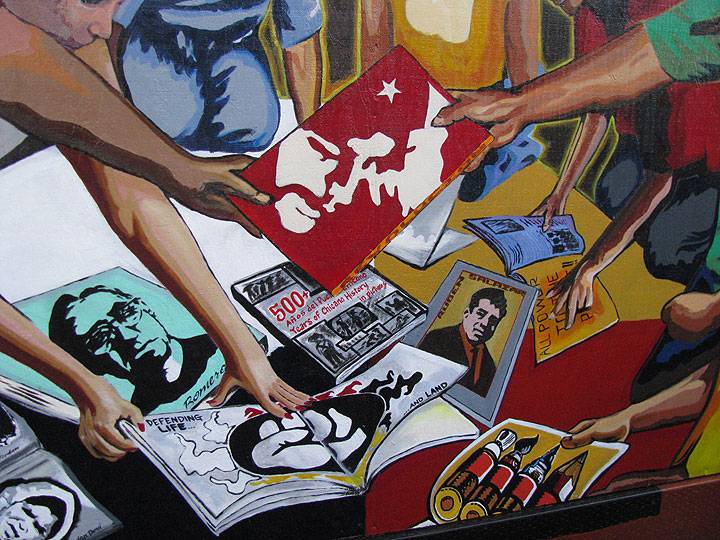

The title of the piece is Solidarity: Breaking Down Barriers. Taking unity as a starting point, the artists began by brainstorming about the influences that divide people, communities, and cultures: everything from national boundaries to gang-affiliated colors. No national flags appear in the 100-foot-long painting. The United States-Mexico border wall figures prominently, snaking through the background of the mural’s central panels, but it’s juxtaposed with portrayals of intra-and inter-ethnic alliance in the foreground. Mexican Revolucionarios, members of the United Farm Workers, and Brown Berets, all painted in sepia tones, float beneficently behind modern-day Raza activists wearing white tees and white bandanas—a purposefully neutral color warn nationwide by Latino youths during the immigrant rights rallies of May 1, 2006. In the Bay Area, many of those activists were HOMEY members.

The cover of the original Los Siete organizing newspaper is prominently featured next to a wall, alluding to the Israeli wall around Palestinian territories, but also to the wall being built between the U.S. and Mexico...

As celebratory as the painting is, one controversial panel on its far right-hand side threatened to overshadow the entire project. It’s a portrayal of the Palestinians garbed in traditional Arab kaffiyeh head scarves breaking through a concrete wall—ostensibly the Israeli West Bank security barrier. the image fits into a third-world rights vignette expressing solidarity with indigenous groups and colonized peoples.

Some members of the San Francisco’s Jewish community took issue with the image, which originally included a hole in the wall in the shape of the state of Israel. two Jewish advocacy groups, the Jewish Community Relations Council and the Anti-Defamation League, brought these concerns to the San Francisco Arts Commission, the board charged with approving all public art. “We thought this one panel was disjointed from the rest of the mural,” JCRC associated director Abby Michelson Porth recalls telling HOMEY and the Arts Commission at a public forum in August 2007. “It didn’t demonstrate peaceful coexistence, which is, frankly, contrary to the theme of the work.”

Rather than battle it out and fling loaded accusations of censorship and anti-Zionism at each other—which would indeed completely contradict the intent of the community-building project—the two factions engaged in a civil dialogue that turned out to be a learning experience for all. HOMEY agreed to make some changes to the imagery: the kaffiyeh shrouding one figure’s face, which the JCRC and the ADL claimed connoted terrorism, is now pulled back and worn as a simple Muslim head scarf; the wall opening now breaks into an expansive blue sky; and the branches of an olive tree now weave around the wall—a symbol of peace and a near-literal olive branch. Still, according to Porth, “It’s not the imagery we would choose, but we recognize the muralists made significant changes and that they came far from the original design.”

Hernandez is quick to point out that many Jewish San Franciscans supported the original design and that several of the artists are in fact Jewish. But she acknowledges that “when we’re painting somebody else’s culture, we have to be humble. We have to say, ‘You know what? We don’t know everything about everybody, but we do know about ourselves, and we’re trying to draw parallels between ourselves and other peoples’.”

To many, it may come as a surprise that the mural’s Palestinian imagery was so controversial. After all, claiming solidarity the Palestine is a common stance among San Francisco’s radical left. Nonetheless, by giving their input, the mural’s detractors wound up being collaborators on a project authored by, as it turned out, truly disparate voices in the community.

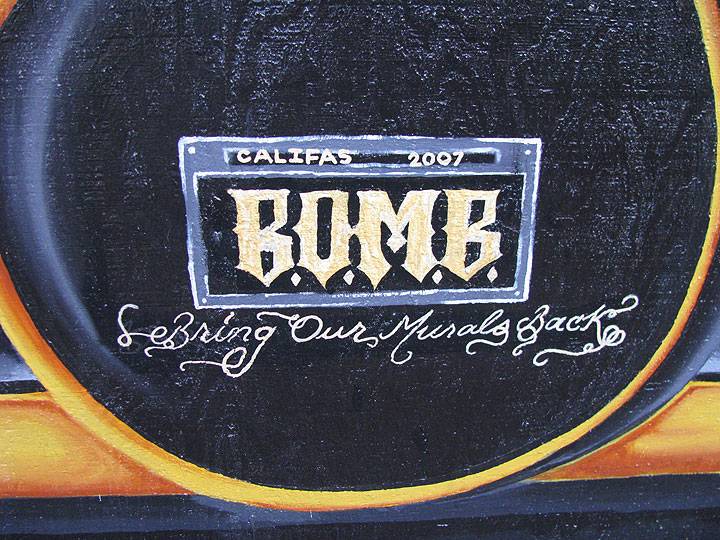

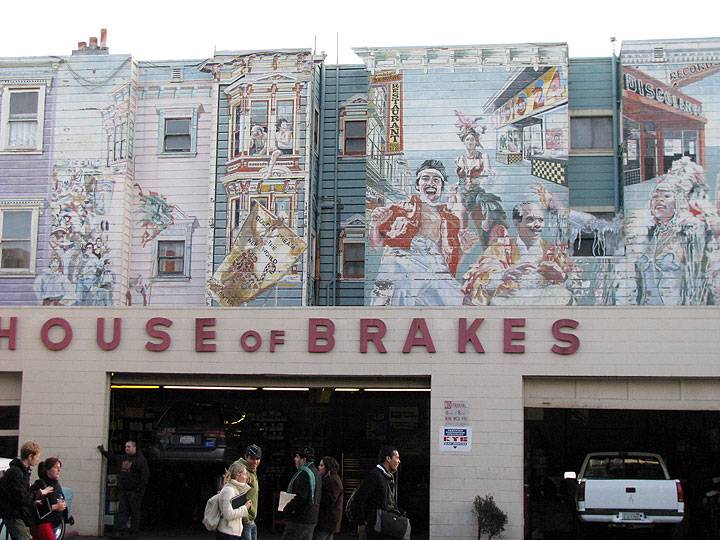

Given its central location to so many other historic murals in the Mission, this detail, on the license plate near the Zoot-suited character and Frieda Kahlo, has special resonance. A block away, above the House of Brakes, this classic Mission mural is slowly fading away, underscoring the poignant plea in the new H.O.M.E.Y. mural...

24th and South Van Ness

Photos: Chris Carlsson

After repainting in 2014.

Photo: Chris Carlsson