California's Not So Radical New Deal Murals: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

upgraded photo |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | |||

''' | ''by Steven M. Gelber'' | ||

[[Image:Maxine-Albro Coit-Tower 9980.jpg]] | |||

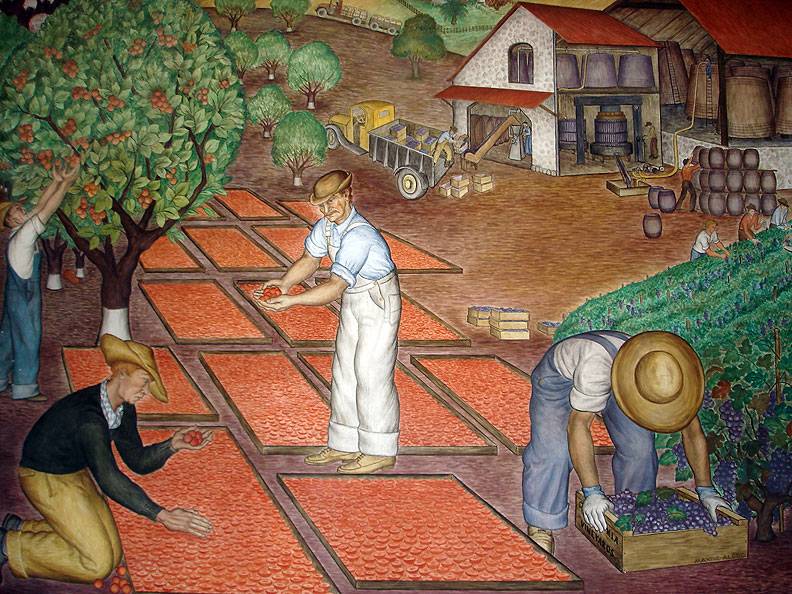

'''Apricot harvesters in Maxine Albro's Coit Tower mural show the pro-work theme that underlay most New Deal murals''' | |||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | ''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | ||

[[Image: | [[Image:Waterfront 3667.jpg]] | ||

'''Panel from the New Deal [[Beach Chalet |Beach Chalet]] murals, suggesting, in typical WPA fashion, that work was the key to economic prosperity.''' | '''Panel from the New Deal [[Beach Chalet |Beach Chalet]] murals, suggesting, in typical WPA fashion, that work was the key to economic prosperity.''' | ||

Latest revision as of 15:20, 7 September 2018

Historical Essay

by Steven M. Gelber

Apricot harvesters in Maxine Albro's Coit Tower mural show the pro-work theme that underlay most New Deal murals

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Panel from the New Deal Beach Chalet murals, suggesting, in typical WPA fashion, that work was the key to economic prosperity.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Announcing in 1933 that artists needed "to eat just like other people," New Deal relief administrator Harry L. Hopkins gave his support to a groundbreaking plan to commission artists to produce public works of art.1 Hopkins argued that "work relief," as it was termed, was necessary because it not only provided otherwise jobless people with money to buy food, but also preserved their skills and restored their self-confidence.2 In addition, work relief brought the government something in return for its money--unlike the more traditional "dole" or cash handout.

In the midst of the greatest depression in American history, then, the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt committed itself to the idea that artists, no less than other Americans, deserved the opportunity to use their particular abilities in government employment until the private sector could once more provide them with a living.

California artists responded to the federally supported art projects by covering the state---from Eureka in the north to Calexico in the south---with murals that celebrated the same values the New Dealers were seeking to preserve. Libraries, court houses, post offices and schools came alive with the color and images of the American people. These New Deal artists, like the president and his administration, carried deep faith in the traditional American values of democracy and private enterprise.

Despite the criticisms in the press to the contrary, the vast majority of the artists rejected Marxist revolutionary solutions to the nation's problems, and their images accordingly emphasized that work rather than political action would bring a return to prosperity. This is not to say that all California artists were politically conservative. As supporters of New Deal programs, most were strong liberals who applauded efforts by the federal government to alleviate the gross suffering caused by the country's economic collapse. Theirs was a commitment to change, it was revealed, but to change that would restore healthy social and economic conditions in America, not revolutionary change that would create a radically new society. . .

. . . The history which appears in the murals by California artists does not reflect a full spectrum of historical events, but rather those aspects which served the artists' didactic purposes. The "search for a usable American past" was a widespread cultural phenomenon in the 1930s, and intellectuals of every discipline looked backward to find solutions to contemporary problems.62 Since work and struggle against adversity were values held in high esteem, artists used history to illustrate how goals could be reached through sacrifice and hard work.

Commenting on Victor Arnautoff's George Washington High School murals, San Francisco Chronicle critic Alfred Frankenstein praised the artist for not painting a "prissy, Parson Weemsish" Washington, but the "granite, laconic, human being, who fought a nation into existence on the edge of a wilderness against the odds of nature and of man."63

Reflecting the artists' search for special values, pre-Columbian Indian societies received short shrift in most New Deal murals. Native American culture, if shown at all, only prefaced the arrival of European civilization. California history seemingly began with the arrival of the Franciscan missionaries who were repeatedly shown instructing obedient Indians in spiritual and material affairs.

Willingly receiving the benefits of the superior European culture, the Indians helped mural viewers feel secure in their values, despite hard economic times, and proud of their treatment of Native Americans.64 Indians who refused to accept the white man's civilization accordingly were rendered as obstacles to be overcome: William Atkinson's Indians in Santa Barbara interfered with the US mail service, Anton Refregier's Indians in San Francisco's Rincon Annex Post Office attacked California-bound settlers, and the flying arrow of Primo Caredio's Indian in San Francisco's Beach Chalet curiously pointed the way to the men's room and menaced its vulnerable occupants.65 . . .

. . . More than 200 artists painted government-sponsored murals in California during the New Deal years. Most of them were young, and many entered the government projects directly from art schools where they had been influenced by a wide variety of historical styles. Although both the individual styles of the mature painters and the historical influences on the younger ones are readily recognized in the murals, it is the uniformity of both form and content that most impress the contemporary viewer. With extraordinarily rare exceptions, the artists painted the same kinds of people doing the same kinds of things, and personal variations in style rarely carried their murals beyond a middle ground between academic traditionalism and modernism. While artists had to please local patrons, and common sense demanded some relation between a mural's subject matter and the place where it appeared, local differences proved less important than the similarities. No matter which federal agency sponsored it, no matter where it was painted, no matter whether it was a mural, easel painting, or print, California's New Deal art reflected the shared values of the artists and the New Deal administration.

Because of their belief in the underlying strength of American institutions, California's New Deal artists readily adapted their art to the requirements of the government's various art projects. Both the federal art bureaucrats and the artists started from the same set of assumptions and proceeded toward the same artistic goals. Both sought American subjects rendered in an American style for the American people. Conflicts among the government, the local audience, and the artists rarely occurred because all three groups knew what they liked. They liked the "American Scene."

The art movement known as the "American Scene" dominated the depression decade that was inevitably linked with the New Deal art projects. Surveying federally sponsored art in early 1938, California art critic Alfred Neumeyer concluded that "an overwhelming majority of the artists naively accept that most obvious and perhaps the most natural of all possible subject matter--the daily life of America." Displeased by the fact that in every city you can now see how cows are milked," he asked, "What terrible spiritual poverty must we confess to our successors, if we believe that American life means nothing but canned food production or the banking business."3 But Neumeyer missed the entire point of New Deal art. The prosaic subjects did not reflect spiritual poverty. Quite the contrary, they were to represent the spiritual strength of the nation--its people and their work. Accordingly, people and work constituted the iconographic essence of the American Scene art movement.

The experimental modernism of cubism, futurism, and the like had been on the decline in America for more than a decade by the time of the great stock market crash of late 1929.4 Even before Roosevelt took office, art critics had begun hailing the emergence of the new American Scene school of art.5 American Scene artists shunned the artistic "Isms" of Paris and sought to paint American subjects in a representational style. Edward Bruce, head of the first government art program, recognized that the popular American Scene movement was totally compatible with his own belief in the value of bringing art out of museums to people, and in 1934 he officially designated "the American Scene" as the appropriate subject matter for all Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) art.6 Thus, the federal government did not originate and impose the American Scene on its artists, but rather commissioned the style and subject from a pre-existing trend. As PWAP, the first government art agency, observed in 1934, "The American artist had just gone through a period of eclecticism, but, a few years before the beginning of the project he turned his mind away from theorizing for its own sake toward the life and people of his own country."7

Within the American Scene, art historians identify two sub-groups of artists, Regionalists and Social Realists. Largely an iconographic distinction, Regionalists painted rural America, and Social Realists painted urban America. Both groups shunned the more abstract elements of European modernism, but the Regionalists went much further than the Social Realists in purging from their work any hint of non-objective styles. They painted little else but their native Midwest, making Regionalism "an art of rural and country views, apolitical in content, often nostalgic in spirit and usually unmindful of the effects of the Depression."8

Social Realists on the other hand were explicit critics of "the system," or at least of the effects of the economic system on people. They saw the depression as an inescapable reality, and they neither retreated to the corn-fed myths of the bucolic Midwest nor glorified workers in the tradition of Socialist Realism. "Despite ample [radical] rhetoric," notes art historian Matthew Baigell, Social Realists "portrayed their subjects as sad, drab, and spiritually depressed individuals rather than as heroic workers bursting with the kind of vitality capable of building a new society."9

Most Social Realists painted in New York, which was the only state that had more extensive art projects than California. There they joined Regionalists to present a full spectrum of contrasting views of America in the thirties.10 In California, however, the Regionalists' outlook totally eclipsed that of the Social Realists. Social Realism was an expression of disenchantment with the economic system that California artists did not share. Men and women who had found a place on the government payroll and who were far removed from both the cultural and political ferment of New York had little reason to upset the status quo. "On the whole the western projects were more naive," observed Federal Art project (FAP) administrator Joseph Danysh in a recent interview. "You could feel the cultural greenhorn quality. On the whole you found them trying harder, and on the whole you found much less of a politically social consciousness." Danysh attributed the difference to the fact that New York "had a very, very strong Communist element" that was missing in the Far West.11

In California, New Deal artists accepted Regionalism, urbanized it where necessary, and applied its uniquely American perspective to the people, places, and history of their state. Theirs was an art of affirmative nationalism that found value in even the most everyday situations and things. The ability of California artists to find beauty in common objects drew notice from as far away as Boston, where in 1934 the Christian Science Monitor praised the artists who wove "such prosaic things as post office boxes, crates of vegetables, a ticker tape apparatus, factory buildings, and even an ash can into a poetic, if slightly grim, whole."12 Both artists and critics gloried in the fact that native artists were painting native subjects. Writing in I937 about the work of San Diego sculptor Donal Hord, Stanton Macdonald-Wright boasted that Hord "has never been abroad, nor has he studied under the influence of foreign masters; his work represents in a marvelous way what the American artist is capable of doing-uninfluenced and untaught by over-seas dictates."13

The return to figurative art was particularly welcomed by the culturally isolated California artists, few of whom had ever accepted modern art and were pleased to find the pendulum of national taste swinging back in their direction. According to surrealist artist Reuben Kadish, who was also an administrator for the Federal Art project (FAP) in San Francisco, California art was generally "mediocre and insipid." The entire state, argued Kadish, was "saturated with provincialism." The galleries would not show, the museums and patrons would not buy, and the critics would not praise anything that was not representational.14 Fortunately for California artists, the American Scene made provincialism a virtue.15

In the 1930s most segments of American society seemed able to agree that American Scene art was appropriate for the era. The public liked it because they could easily understand it. California artists liked it because it was not oriented toward Europe. Government administrators liked it because it supported rather than challenged New Deal values. Thus, while painting for the government imposed certain limits on what was acceptable art, most California artists had already imposed the same restrictions on themselves.

--excerpted from "Working to Prosperity: California's New Deal Murals" by Steven M. Gelber in California History magazine, Summer 1979, Vol. LVIII, No. 2

article excerpted with permission of California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA