Ferries on the Bay: Difference between revisions

(added image) |

(fixed broken video link code) |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

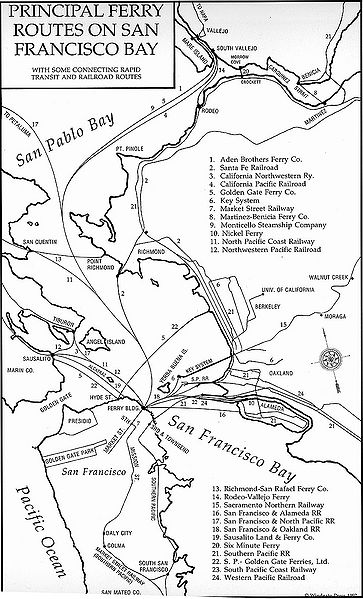

[[Image:Principal-ferry-routes-on-SF-Bay.jpg|363px|thumb|left]] Ferries crisscrossed the Bay by the dozens every day. Over the last century and a half, over two dozen major cross-bay ferry lines existed, serving 29 destinations. The Golden Era of ferry transit stretched from the 1870s to its peak in the 1930s. Ten million passengers went through the Ferry Building in the first decade of the 20th century and just thirty years later there were 60 million annual bay crossings, along with 6 million autos. 250,000 daily commuters travelled through the Ferry Building to work or other destinations. Ferries made approximately 170 landings a day at this time, and the Ferry Building was served by trolley lines which left every 20 seconds for city destinations. The ferry was as deeply rooted in the daily lives of San Franciscans as cars and planes are now. When [[TOM MOONEY|Tom Mooney]] was finally pardoned from jail in 1939 (where he served 22 ½ years for the bombing of the July 22, 1916 Prepardeness Day March—a crime he demonstrably did not commit) he left San Quentin Prison by ferry and went to Sacramento to receive his pardon from Governor Culbert Olson. After the pardon and press conference he returned to San Francisco by ferry where he was greeted by 10,000 well-wishers as he emerged from the Ferry Building into Market Street. | [[Image:Principal-ferry-routes-on-SF-Bay.jpg|363px|thumb|left]] Ferries crisscrossed the Bay by the dozens every day. Over the last century and a half, over two dozen major cross-bay ferry lines existed, serving 29 destinations. The Golden Era of ferry transit stretched from the 1870s to its peak in the 1930s. Ten million passengers went through the Ferry Building in the first decade of the 20th century and just thirty years later there were 60 million annual bay crossings, along with 6 million autos. 250,000 daily commuters travelled through the Ferry Building to work or other destinations. Ferries made approximately 170 landings a day at this time, and the Ferry Building was served by trolley lines which left every 20 seconds for city destinations. The ferry was as deeply rooted in the daily lives of San Franciscans as cars and planes are now. When [[TOM MOONEY|Tom Mooney]] was finally pardoned from jail in 1939 (where he served 22 ½ years for the bombing of the July 22, 1916 Prepardeness Day March—a crime he demonstrably did not commit) he left San Quentin Prison by ferry and went to Sacramento to receive his pardon from Governor Culbert Olson. After the pardon and press conference he returned to San Francisco by ferry where he was greeted by 10,000 well-wishers as he emerged from the Ferry Building into Market Street. | ||

< | <iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/FerriesPlyTheBay" width="640" height="506" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe> | ||

''Video: Silent footage from the [http://www.archive.org/details/prelinger Prelinger Archive], probably from the 1920s.'' | ''Video: Silent footage from the [http://www.archive.org/details/prelinger Prelinger Archive], probably from the 1920s.'' | ||

Revision as of 00:55, 28 August 2016

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

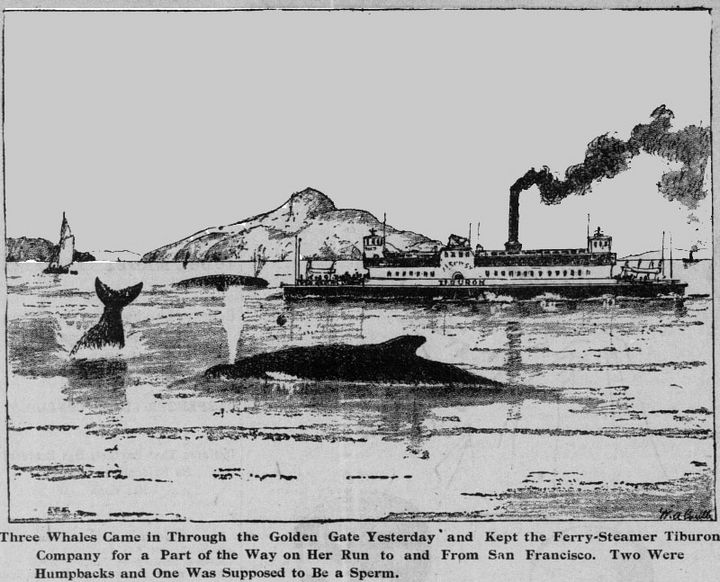

William Coulter was a maritime artist who also drew for the local press. This 1896 image depicts three whales inside the bay near a Sausalito-bound ferry.

Image: San Francisco Call, 1896, from The Cable Car Guy]

There are thousands of people using ferries on the San Francisco Bay these days, so it’s hard to remember that ferry service died out for several decades after the construction of the Bay Bridge and Golden Gate Bridge. Of course the long history of Bay Area mobility is a story of water travel. Whether moving hay into the City to feed the thousands of horses pulling wagons and omnibuses, or bringing the lumber in to build the wooden City, or taking big loads of grain or (by the early 20th century) canned fruit and vegetables to far-flung ports, everything came and went by ship for a long time. But it was also true that most people wanting to go from one part of the Bay Area to another would find ferry travel the most convenient and appropriate means to make their trip.

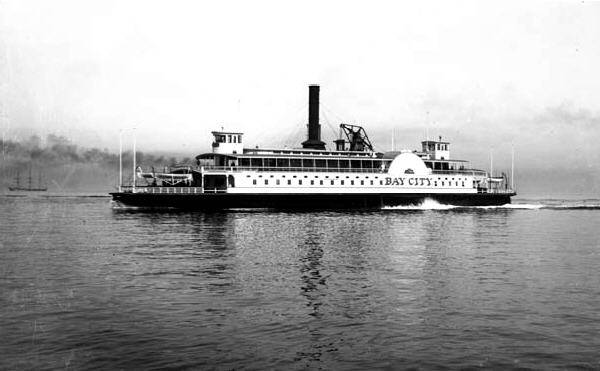

The Southern Pacific Company's Bay City ferry plies the waters of San Francisco Bay sometime between 1870 and 1900.

Photo: California Historical Society, J1211

In 1850, just a year since the beginning of urbanization, the first ferry service was established between San Francisco and Oakland, running across sand bars to San Antonio Creek, better known now as the Oakland Estuary. Ferries were the main transportation choice for travelers between San Francisco and Sacramento, and points in between, and continued to be well into the 20th century. Back in 1862 the San Francisco and Oakland Railroad Company built a ¾ mile pier from West Oakland into the Bay. Thus begins a decades-long concentration of cross-bay ferry traffic between West Oakland and San Francisco’s Ferry Building. After the Civil War in 1868 real estate promoters laid out streets and docks in Sausalito and begin providing North Bay ferry service. When the first transcontinental railroads spanned the country, the original terminal was in Sacramento where passengers transferred to fast ferries to finish their trip to San Francisco and the coast. Before long the new railroad barons had acquired the local ferry services and by 1881 they extended the wharves well into the Bay on what became known as the Oakland Mole, where trains and ferries met in the Bay all the way to 1957.

The Oakland Mole ferry slip in the early 1900s.

Photo: Bancroft Library, 1905.17146-17161

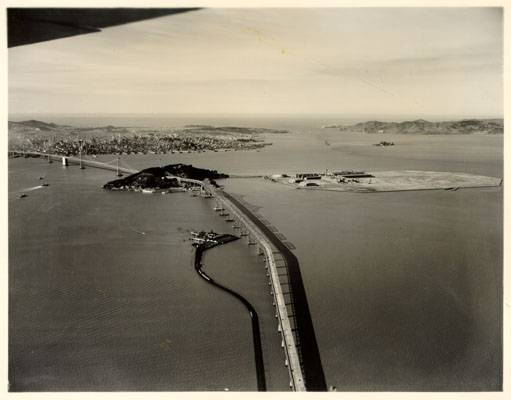

The Oakland Mole snakes out next to the new Bay Bridge in this 1938 photo, with Treasure Island just being constructed in background.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

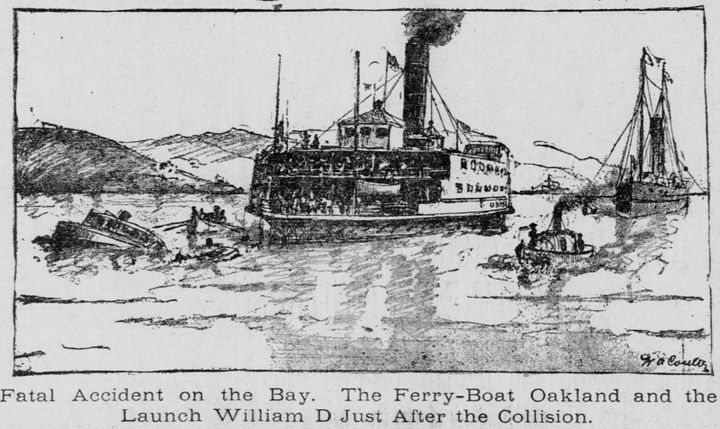

Another Coulter image, this one of the Ferry Oakland that had just collided with a small skiff near Goat Island (now Yerba Buena Island).

Image: San Francisco Call, 1896, from The Cable Car Guy]

John Leale was a San Francisco ferryboat captain for four decades spanning the last quarter of the 19th century until just before WWI. He lived long enough to see the opening of the Bay Bridge that would nearly destroy ferry service in the Bay Area. His memoir, “Recollections of a Tule Sailor,” captures a San Francisco and water-borne life that is long-forgotten now. ("Tule sailor" is a disparaging epithet once applied to inland boatmen by blue water sailors. The bulrush or tule, with its long hollow reed-like spikes, filled thousands of acres of delta lands in the lower reaches of the Sacramento River.)

On his arrival in San Francisco in 1864 he docked at the Folsom Street Wharf and from there took a horse-drawn omnibus to the Third Street Wharf, then jutting into Mission Bay:

“A whitehall boatman rowed us over to the Potrero to the home of a relative, at a point which later became the Union Iron Works [Today’s 3rd Street and 20th Street]. Third Street at that time ended at about Townsend Street or Steamboat Point. Between there and the Potrero was a large bay at the head of which was San Francisco’s first Butchertown [close to Costco at 10th and Bryant]. I later learned that it was a long way by land from the Potrero to Third Street with its mud and unpaved road… The morning after my arrival, I meandered to the top of a nearby hill, and after surveying the beautiful bay and mountains before me and I realized that I was indeed in California.”

"My first job in California was cook of the Schooner "Emma Adelia" of which Captain Andrew Nelson was captain and owner. My work was not cooking alone but also tending the jib sheet and working cargo. During the summer we ran in the fruit trade [up and down the Sacramento River]. The passengers who got on board well up river had a whole day’s entertainment plus looking for a cool spot, for a summer day on the Sacramento is "heap hot." Rio Vista was usually the last landing and the boys would turn in for about five hours, to be called when Angel Island was reached, for we must have coffee before beginning to discharge. This would be perhaps three or four o’clock in the morning, and if it happened to be low water with the corresponding steep gangway plank, it was a tough job. At about 11:30 AM we would leave the city again for the next trip. So it will be seen that the life of a deckhand on the river in those days was a bit strenuous."

Ferries crisscrossed the Bay by the dozens every day. Over the last century and a half, over two dozen major cross-bay ferry lines existed, serving 29 destinations. The Golden Era of ferry transit stretched from the 1870s to its peak in the 1930s. Ten million passengers went through the Ferry Building in the first decade of the 20th century and just thirty years later there were 60 million annual bay crossings, along with 6 million autos. 250,000 daily commuters travelled through the Ferry Building to work or other destinations. Ferries made approximately 170 landings a day at this time, and the Ferry Building was served by trolley lines which left every 20 seconds for city destinations. The ferry was as deeply rooted in the daily lives of San Franciscans as cars and planes are now. When Tom Mooney was finally pardoned from jail in 1939 (where he served 22 ½ years for the bombing of the July 22, 1916 Prepardeness Day March—a crime he demonstrably did not commit) he left San Quentin Prison by ferry and went to Sacramento to receive his pardon from Governor Culbert Olson. After the pardon and press conference he returned to San Francisco by ferry where he was greeted by 10,000 well-wishers as he emerged from the Ferry Building into Market Street.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/FerriesPlyTheBay" width="640" height="506" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Video: Silent footage from the Prelinger Archive, probably from the 1920s.

By the end of the 1930s the two great bridges were complete and the patterns of urban life and cross-bay travel were altered forever. The great urban theorist Lewis Mumford had no trouble in 1963 describing what the Bay Bridge had done to Ferry travel:

"The Bay Bridge, between San Francisco and Oakland, brought far greater damage than benefits to both cities: it pumped up a once unnecessary volume of private traffic between them, at a great expense in expressway building and at a great waste in time and tension, spent crawling through rush-hour congestion. This traffic eventually wiped out, by impoverishment, the excellent rapid transit that had been installed on the Bay Bridge (the [[Key System and March of Progress|Key System]) a form of transportation that the citizens of San Francisco have now repentantly voted to restore [the BART system], at an expense far greater than the cost of the original system. The ferry ride across the bay from Oakland was one of the region’s greatest recreational resources — an incomparable experience, so exhilarating, at almost any time of the day, that one often sought an excuse for making the journey. It was not a long ride — not more than twenty-five minutes or so, and certainly not longer than the present depressing rush-hour crawl over the bridge."

A similar story follows the ever-popular Golden Gate Bridge, which opened in May 1937. Flourishing ferry service between Sausalito and San Francisco rapidly declined after the Bridge opened, stopping entirely by 1941. For the next 29 years the only way to get from San Francisco to Marin County and points north was by driving across the Golden Gate Bridge. During those same three decades motor traffic on the Golden Gate Bridge went from 3.3 million trips at the beginning to 28.3 million by the late 1960s. Local traffic planners and highway engineers had proposed new bridges to cross the Bay from Telegraph Hill to Angel Island and Tiburon, but they had not gotten off the drawing boards.

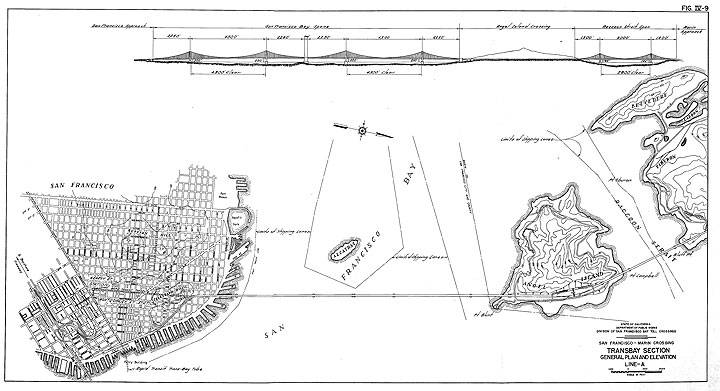

A rendering of a planned bridge from San Francisco north across Angel Island and through Tiburon.

Thanks to Eric Fischer for making this image, and many more, all in high resolution, available at his flickr account.

Instead, the indomitable ferry came back into the picture. In August 1970 a newly minted Golden Gate Ferry service began from Sausalito to San Francisco. By the end of December 1976 the Larkspur Ferry began its service. It was another year and a half before the familiar Golden Gate Ferry terminal behind the Ferry Building was dedicated in summer 1978. Golden Gate Transit provides a decent history of itself, as well as this overview of its current service:

GGF operates two commute passenger ferry routes across the San Francisco Bay that connect Marin County and the City and County of San Francisco: (1) Larkspur/San Francisco: 11.25 nautical miles/13.01 statute miles, and (2) Sausalito/San Francisco: 5.5 nautical miles/6.33 statute miles. Today, GGF operates 41 weekday crossings and 9 weekend/holiday crossings on the Larkspur-San Francisco route; 18 weekday crossings and 13 weekends/holiday crossings on the Sausalito/San Francisco. Since March 31, 2000, dedicated San Francisco Giants Baseball Ferry Service has been provided between Larkspur and the newly opened waterfront ball park located in downtown San Francisco. This special service has become a favorite mode of transportation from the North Bay to the ballpark due to its convenience.

Ferries offloading passengers for a Giants game in 2010.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

One of the untold stories of the current Golden Gate Ferry service is that at least two of the daily runs between Sausalito and San Francisco are able to keep running thanks to the revenue provided by bicycle-renting tourists who ride across the Golden Gate Bridge and return by Ferry!

The Vallejo Ferry Service only recommenced in 1986, initially as a commercial operation of the Red & White Fleet in San Francisco to shuttle midday visitors north to the newly opened Marine World in Vallejo, and commuters back and forth in morning and evening runs. The commuter runs proved unprofitable and within a few years the city of Vallejo had to take over the service under strong pressure from its ferry riding citizens.

The Bay Ferry operations all got a big boost when the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake knocked out the Bay Bridge for several months. State transportation money was made available to excursion and tour boats while also bolstering existing public ferry services. The network of ferries established under pressure from clogged freeways and a basically dysfunctional automobile-based transit system seemed to finally solidify with a new public awareness of their indispensability. After a week-long BART strike in 1997, ferry passengers surged again, and as of a few years ago, the Vallejo Baylink service was running three daily ferries back and forth.

The ferry’s future is bright. Water-borne transportation is likely to enjoy a considerable expansion whether due to high oil prices, impassable traffic jams, or just an embrace of a more civilized way to move across our beautiful Bay.