Destruction of the Fair: Difference between revisions

m (changed photo caption to indicate it was an Italian Tower coming down, not the Tower of Jewels per R. Christian Anderson) |

(added link to GGIE) |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

'''TREASURE ISLAND ''' | '''TREASURE ISLAND ''' | ||

The Panama Pacific International Exposition, although it had little immediate effect on the architecture of the Bay Area, was reincarnated twenty-four years later in the form of "Treasure Island," the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939-40. The design team of that fair was headed by Arthur Brown, Jr., designer of the San Francisco City Hall and the Horticulture Palace at the Panama Pacific International Exposition and, by 1939, the dean of reactionary classicism in American architecture. Working closely with Brown were a number of architects who had designed buildings or courts at the earlier world's fair, or who vividly remembered it. So potent was the memory of the Panama Pacific International Exposition that the architects simply built a stripped, Moderne version of the earlier fair in the middle of the Bay. High walls designed to block the wind sheltered enclosed thematic courts with cosmic names, Jessie Stanton played the role of Jules Guerin as master colorist, and colored, indirect lighting was used once again. Eastern exoticism again prevailed with the use of Cambodian, Malaysian and even Aztec and Incan motifs combined with modernized classicism. Aged wall surfaces were attempted with stucco mixed with vermiculite, and even the Tower of Jewels was reborn as Brown's Tower of the Sun. | The Panama Pacific International Exposition, although it had little immediate effect on the architecture of the Bay Area, was reincarnated twenty-four years later in the form of [[Treasure Island Fair: Golden Gate International Exposition|"Treasure Island," the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939-40]]. The design team of that fair was headed by Arthur Brown, Jr., designer of the San Francisco City Hall and the Horticulture Palace at the Panama Pacific International Exposition and, by 1939, the dean of reactionary classicism in American architecture. Working closely with Brown were a number of architects who had designed buildings or courts at the earlier world's fair, or who vividly remembered it. So potent was the memory of the Panama Pacific International Exposition that the architects simply built a stripped, Moderne version of the earlier fair in the middle of the Bay. High walls designed to block the wind sheltered enclosed thematic courts with cosmic names, Jessie Stanton played the role of Jules Guerin as master colorist, and colored, indirect lighting was used once again. Eastern exoticism again prevailed with the use of Cambodian, Malaysian and even Aztec and Incan motifs combined with modernized classicism. Aged wall surfaces were attempted with stucco mixed with vermiculite, and even the Tower of Jewels was reborn as Brown's Tower of the Sun. | ||

Treasure Island, even more than the Panama Pacific International Exposition, was an exposition out of its time. The Chicago Century of Progress in 1933 had pointed the way toward modernistic architecture and the disintegration of beaux-arts ensemble planning that had been such a marked feature of earlier fairs since the 1893 exposition. The fair at Flushing in 1939 also looked to the future, while the fair in San Francisco was a nostalgic nod to the past. Treasure Island was a poor compromise, for the Panama Pacific International Exposition was in all respects the greater exposition; even the vermiculite plaster, it was noted, looked tawdry when compared with the earlier travertine. Built around its courts, pervaded with art and fountains, oriented to the pedestrian, Treasure Island was anything but a vision of the urban American future, for already, in architectural magazines, visionary sketches of modernist slabs in freeway-encircled plazas hailed the advent of corporate modernism. The future lay not in arcaded dream cities, in artifices of eternity, but in urban redevelopment. | Treasure Island, even more than the Panama Pacific International Exposition, was an exposition out of its time. The Chicago Century of Progress in 1933 had pointed the way toward modernistic architecture and the disintegration of beaux-arts ensemble planning that had been such a marked feature of earlier fairs since the 1893 exposition. The fair at Flushing in 1939 also looked to the future, while the fair in San Francisco was a nostalgic nod to the past. Treasure Island was a poor compromise, for the Panama Pacific International Exposition was in all respects the greater exposition; even the vermiculite plaster, it was noted, looked tawdry when compared with the earlier travertine. Built around its courts, pervaded with art and fountains, oriented to the pedestrian, Treasure Island was anything but a vision of the urban American future, for already, in architectural magazines, visionary sketches of modernist slabs in freeway-encircled plazas hailed the advent of corporate modernism. The future lay not in arcaded dream cities, in artifices of eternity, but in urban redevelopment. | ||

Revision as of 00:03, 4 February 2016

Historical Essay

by Gray Brechin

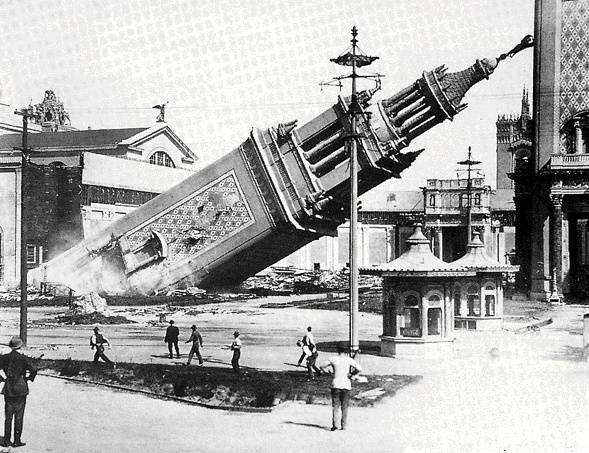

One of four Italian Towers comes crashing down at the end of the Panama-Pacific Exposition, 1916.

| Gray Brechin discusses the legacies of the Panama Pacific International Exposition (1915-1916) at the time of its destruction. From dreams of preserving the fair’s structures as an architectural unit, to the belief that the Fair would forever change the mechanisms of city planning, he examines the reasons for its popularity and its symbolism as the last of the great Beaux-Arts Fairs, and discusses the work of the few architects and projects that were deeply affected by its legacy. |

The Panama Pacific International Exposition proved so popular (and profitable) that long before its closing proposals were being made to save all or part of it. Architect Willis Polk, in particular, lobbied heavily for the preservation of the Palace of Fine Arts, Palace of Horticulture, South and North Gardens, and the Avenue of Palms. Louis Christian Mullgardt told the Commonwealth Club that "when the Exposition buildings are torn down, then we will have destroyed one of the greatest architectural units which has ever been created in the history of the world."32 The influential club, like many others, passed a resolution pleading for the preservation of as much of the fair as possible.

Speculative forces proved far stronger than the dream, however, and the arches and towers were brought down in clouds of colored plaster, revealing in their fall the underlying lath framework. The South Gardens were scraped clean of plantings, fountains, and sculpture, and small buildings were moved to the waterfront and barged throughout the Bay Area. The North Gardens (Marina Green) and Yacht Harbor remained, a gift of the Exposition, along with the Column of Progress with its "Adventurous Bowman" at the end of Scott Street until, in the 1920s, it succumbed to automobile collisions and was pulled down. The immense California Building, just north of the Palace of Fine Arts, was seriously proposed for a State Normal School, and Maybeck prepared plans for converting the rotunda of his Palace into an adjacent auditorium while remodeling the entire Palace in a sympathetic Mission style. As plans fell through, the California Building was razed as well, leaving only the Palace of Fine Arts, fortunately unremodeled, to decay by its lagoon. The nearby French Pavilion was reerected in permanent materials in Lincoln Park as the Palace of the Legion of Honor, a copy of a copy of the original Legion of Honor in Paris.

It was altogether appropriate that the Panama Pacific International Exposition fell when it did, for it had opened beyond its rightful era, the last of the great beaux-arts fairs. The guns of August in Europe proclaimed a new age and throughout the summer and fall of 1915 news arrived of unprecedented carnage and destruction. Frank Morton Todd lamented:

The general feeling of helplessness and of endless tragedy was aggravated by the fact that every great teacher that had declared war among civilized nations to be no longer possible was proved to be wrong, and no prophet that promised security to life and prosperity and family and love and culture and other things of peace that make life worth while, was any more to be believed.33

While only a Henry Adams might then have perceived the emblems of aggression and oppression that permeated the fair, the war assured that it would never again be possible to so uncritically celebrate the steady ascension of Progress, Technology and Civilization.

LEGACY

Many predictions were made that the Panama Pacific International Exposition would mark a new era in town planning and a revolution in Western architecture. However, it was the simultaneous San Diego exposition of 1915-1916 that had the far greater influence through its popularization of the elaborate Churrigueresque style which remained in vogue through the 1920s. Certainly, the San Francisco fair gave impetus to city planning throughout California, but its unique features-the court scheme, the vibrant color, the wholesale use of indirect lighting and the simulation of age-appear to have been possible only at the moment the fair was created, with the possibilities for cooperation and coordination that it presented. It did, however, affect individual architects to a greater or lesser degree.

George Kelham, Chief Architect of the fair and designer of the Courts of Palms and Flowers, became one of the city's leading commercial architects in the 1920s and used Paul Denivelle's artificial travertine extensively for interior finish, most notably in the San Francisco Public Library Of 1917. Essentially conservative, Kelham clad the exteriors of his major buildings with gray granite or terra cotta, while the interiors remain a pale memory of the fair.

The phenomenal success of his Court of the Ages marked an epoch in the career of Louis Christian Mullgardt, who had heretofore largely designed superbly site-sensitive bungalows in the East Bay hills inspired, to some extent, by Tibetan lamasaries. The Panama Pacific International Exposition allowed Mullgardt to design on a monumental scale and to use his extraordinary talent for ornament. Thereafter, Mullgardt received larger commissions. M. H. de Young commissioned Mullgardt to invert the Court of the Ages for a new de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park, incorporating one of W. B. Faville's portals for the front door. (This exotic fantasy was eventually stripped to its present austerity when finials began toppling from the building.) In his 19 14 juvenile Court on Otis Street in San Francisco, Mullgardt created an early slab skyscraper using a buff stucco facing combed to resemble the travertine of the Panama Pacific International Exposition. His 1917 Davies Building for Honolulu featured a block-square building around a courtyard with a fountain, heavily decorated with terra cotta the color of a "ripening mango." His last building, the 1928 Infant Shelter Building at 1201 Ortega Street in the Sunset District, shows his highly idiosyncratic use of ornament and eclecticism, while the color, again, is a legacy of the Panama Pacific International Exposition.34

No one, however, was as influenced by the fair as was Bernard Maybeck. Like Mullgardt, Maybeck had been largely restricted to the residential designs for which he has become so famous. He was fifty when chosen to design the Palace of Fine Arts, and the international attention that building received marked the beginning of a second career. His smaller buildings at the fair, the whimsical House of Hoo-Hoo and the Livestock Building, were much admired, but received nothing like the acclaim given to the grandiloquent Palace.

Maybeck thereafter preferred to work in pastel stucco and often developed his designs in pastel chalks on enormous sheets of brown craft paper. Throughout the 1920s and I 1930s, he gratuitously worked on an ideal scheme for the rebuilding of San Francisco, a memorial plan for the World War I dead, which proposed parks, boulevards and palatial emporia "so that when a stranger visits the Bay Cities he will have the sense of being in a perpetual world's fair of form, color, and lights."35

Maybeck's plans for a wartime workers' town at Clyde near the Carquinez Straits became known as "the Rainbow City" for the lavish use of color on which Maybeck insisted. Houses, he noted, were to look like California wildflowers against the golden hillside.

In a protracted correspondence between Maybeck and leaders of the Australian government and Canberra architect Walter Burley Griffin, Maybeck suggested that as much of the new Australian capital as possible should be built of lath and stucco, like the Panama Pacific International Exposition, to engender public enthusiasm for the plan so that it would see completion in permanent materials. (Griffin, at one point, frostily informed Maybeck that "plaster or stucco are hardly considered as temporary expedients [in Australia] for they are largely employed for buildings both commercial and governmental, already deemed to be permanent.")36

Maybeck best showed the lasting legacy of the Panama Pacific International Exposition on his own late career in the San Francisco and Oakland Packard showrooms for Earle C. Anthony. Both were visible reminders of the fair and were seen by Maybeck as regional responses to the romance of the landscape and the cosmopolitanism of the Bay Area. Of the richly polychromed San Francisco showroom, the San Francisco Examiner reported that Maybeck had "blended the finest features of Spanish, Roman, Gothic, Corinthian, and Byzantine architecture."37 (Its strident color scheme has since been painted a tasteful beige, the Byzantine chandeliers replaced with crystal, and the indirect lights which took it through the phases of the day from dawn to moonlight at twenty-minute intervals have been removed by the present owners)

But it was in the Oakland Packard showroom that Maybeck used his scenographic skills to their utmost. With Lake Merritt as a foreground reflecting lagoon, he concocted a fantasy inspired, he said, by a palace at Isfahan. Its stucco walls with their deeply recessed arches were spatter-painted to suggest that they had been weathered and sun-beaten for centuries, while colored, indirect lights suffused the structure at night. Architect Irving Morrow astutely noted, at the building's completion, that

[in 1915], it was fondly predicted that the Exposition would mark the beginning of a new era in the architecture of San Francisco. For the failure of this hope I can attempt no explanation here. Suffice it to say that Mr. Maybeck seems to be one of the few living persons to recall the lessons of that far-off event.38

(Indeed, when chosen as Consulting Architect for the Golden Gate Bridge, Morrow partly 'Justified his choice of the controversial "international orange" paint by citing the precedent of the fair; the local landscape, he noted, "would imply a free use of color in general in San Francisco architecture; but except for the Panama Pacific International Exposition of almost a quarter of a century ago, architects have continually evaded this obligation."39

Finally, throughout the 1920S,Maybeck worked with Julia Morgan on plans for a Phoebe Apperson Hearst Memorial on the Berkeley campus that would have been a small-scale re-creation, in permanent materials, of the Panama Pacific International Exposition, with polychrome classical buildings and detached architectural groupings resembling ruins enclosing a series of sheltered courts. While only the Hearst Gymnasium was built, and never colored as Maybeck intended, its elegiacal planters almost exactly copy those at the Palace of Fine Arts and its miniature court scheme is reminiscent of the fair's walled city.

TREASURE ISLAND

The Panama Pacific International Exposition, although it had little immediate effect on the architecture of the Bay Area, was reincarnated twenty-four years later in the form of "Treasure Island," the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939-40. The design team of that fair was headed by Arthur Brown, Jr., designer of the San Francisco City Hall and the Horticulture Palace at the Panama Pacific International Exposition and, by 1939, the dean of reactionary classicism in American architecture. Working closely with Brown were a number of architects who had designed buildings or courts at the earlier world's fair, or who vividly remembered it. So potent was the memory of the Panama Pacific International Exposition that the architects simply built a stripped, Moderne version of the earlier fair in the middle of the Bay. High walls designed to block the wind sheltered enclosed thematic courts with cosmic names, Jessie Stanton played the role of Jules Guerin as master colorist, and colored, indirect lighting was used once again. Eastern exoticism again prevailed with the use of Cambodian, Malaysian and even Aztec and Incan motifs combined with modernized classicism. Aged wall surfaces were attempted with stucco mixed with vermiculite, and even the Tower of Jewels was reborn as Brown's Tower of the Sun.

Treasure Island, even more than the Panama Pacific International Exposition, was an exposition out of its time. The Chicago Century of Progress in 1933 had pointed the way toward modernistic architecture and the disintegration of beaux-arts ensemble planning that had been such a marked feature of earlier fairs since the 1893 exposition. The fair at Flushing in 1939 also looked to the future, while the fair in San Francisco was a nostalgic nod to the past. Treasure Island was a poor compromise, for the Panama Pacific International Exposition was in all respects the greater exposition; even the vermiculite plaster, it was noted, looked tawdry when compared with the earlier travertine. Built around its courts, pervaded with art and fountains, oriented to the pedestrian, Treasure Island was anything but a vision of the urban American future, for already, in architectural magazines, visionary sketches of modernist slabs in freeway-encircled plazas hailed the advent of corporate modernism. The future lay not in arcaded dream cities, in artifices of eternity, but in urban redevelopment.

NOTES

1. Edmund Wilson (to Stanley Dell), August 29, 1915, in Letters on Literature and Politics, 1912-1972- (New York, 1977), P. 22.

2. A. C. David, The New San Francisco," The Architectural Record 31, no. 1 (January 1912): 6.

3. 3. Ibid., p. 9.

4. Ernest Coxhead, "A Waterfront Exposition Would Mean Permanent Architecture," Architect and Engineer 33, no. 2, pp. 50-57.

5. Anonymous, "We Don't Want Mission Architecture for the Fair," Architect and Engineer 25, no. 1 (August 1911):102-103.

6. Frank Morton Todd, The Story of the Exposition (New York, London: Putnum's Sons, 1921), 2:283. For an occult exposition on the Exposition, see Cora Lenore Williams, The Fourth -Dimensional Reaches of the Exposition (San Francisco: Paul Elder and Company, 1915)

7. Bernard Maybeck, Palace of Fine Arts and Lagoon (San Francisco: Paul Elder and Company, 1915), P. 2.

8. Todd, The Story of the Exposition, 2:345.

9. Undated promotional brochure in private collection.

10. Mary Austin, "Art Influence in the West," The Century Magazine, April 1915, p. 829.

11. Ibid, p. 830.

12. Ibid.

13. Quoted in Elmer Grey, "The P.P.I.E. Of 1915," Scribners Magazine 54 0915):48.

14. William Woolett, "Color in Architecture at the Panama Pacific Exposition"' Architect and Engineer 42, no. I (July 1915):67.

15. Todd, The Story of the Exposition.

16. Wilson, Letters on Literature and Politics.

17. Anon., "The Exposition Color Scheme," Architect and Engineer 39, no. 2 (December 1914):112.

18. L. C. Mullgardt, The Architecture and Landscape Gardening of the Exposition (San Francisco: Paul Elder & Co., 1915), p. 88.

19. Ben Macomber, The jewel City (San Francisco and Tacoma: John H. Williams, 19 15), P. 27.

20. Ibid., P. 21.

21. Ibid., p. 83.

22. Clinton Scollard , 'At the Golden Horn and the Golden Gate , Over land Monthly, December 1888 and November 1907

23. Quoted in Kevin Starr, Americans and the California Dream (New York, 1973), p. 138.

24. Gelett Burgess, "The Topography of San Francisco," The American Architect and Building News 89 (March 17, 1 906):152.

25. William D'Arcy Ryan, "New Light on an Exposition," Sunset Magazine, March 19 13, p. 293

26. Woolett, Color in Architecture, p. 65.

27. Todd, The Story of the Exposition, 2:3 15-17

28. The best discussion of the Palace of Fine Arts is found in William Jordy, American Buildings and Their Architects (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1972),3:275-300

29. Quoted by Todd, The Story of the Exposition, 2:315.

30. Hamilton M. Wright, "The Miracle Workers of the Exposition," California's Magazine 1, no- 4.

31. Ruth Waldo Newhall, San Francisco's Enchanted Palace (Berkeley, 1967), P- 75.

32. L. C. Mullgardt, Common wealth Transactions, August 19 15, P- 360.

33. Todd, The Story of the Exposition, 2:133.

34. Foremost Mullgardt authority is Professor Robert Judson Clark. See Robert Judson Clark, Louis Christian Mullgardt, 1866-1942 (exhibition catalogue) (Santa Barbara, 1966).

35. Bernard R. Maybeck MSS., "Memorial Plan," Documents Collection, College of Environmental Design, University of California, Berkeley.

36. Walter Burley Griffin, in Maybeck MSS., "Canberra," Documents Collection, College of Environmental Design, University of California, Berkeley.

37. Undated newspaper clipping in Documents Collection, College of Environmental Design, University of California, Berkeley.

38. Irving Morrow, "The Packard Building at Oakland," California Arts and Architecture 35, no. 2 (February 1929):56.

39, Irving Morrow, "Beauty Marks Golden Gate Bridge Design," The Architect and Engineer 128, no- 3 (March 1937): 24.

--by Gray Brechin, (from "Sailing to Byzantium: The Architecture of the Fair" in The Anthroplogy of World's Fairs, edited by Burton Benedict)