San Francisco Tape Music Center: Difference between revisions

m (Protected "San Francisco Tape Center": finished essay [edit=sysop:move=sysop]) |

(added audio) |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

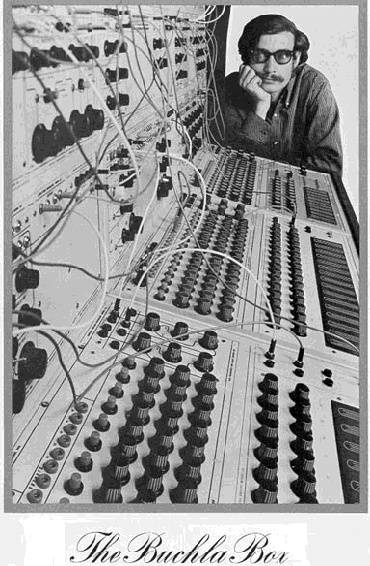

'''Ken Kesey's Buchla synthesizer''' | '''Ken Kesey's Buchla synthesizer''' | ||

<div> | |||

<flashmp3>http://www.archive.org/download/BuchlaSound/buchla.mp3</flashmp3> | |||

</div> | |||

''Buchla sound'' | |||

[[Image:music1$buchla-box.jpg]] | [[Image:music1$buchla-box.jpg]] | ||

Revision as of 21:19, 1 June 2009

Historical Essay

by R. Wiley

Ken Kesey's Buchla synthesizer

<flashmp3>http://www.archive.org/download/BuchlaSound/buchla.mp3</flashmp3>

Buchla sound

Buchla Box

The man's voice you are hearing is Daniel Hamm, describing the beating he took in the Harlem 28th precinct. The police were about to take the boys out to be "cleaned up" and were only taking those who were visibly bleeding. He proceeded to squeeze open the bruise on his leg so that we would be taken to the hospital. He is the subject of Steve Reich's first "phazing" piece which was produced at the San Francisco Tape Center. It is also very significant because it uses a new technology to form a new kind of music, and to some extent, changed the definition of music. Reich was one of many artists (mostly composers) that were just beginning to work with new technologies, such as tape recorders, analog synthesizers and multi-colored light projection.

Pauline Oliveros, Ramon Sender and Morton Subotnick conceived the Tape Center in 1960. It was a place where experimental artists could work together and as individuals, pooling resources and knowledge in an unstructured space. It was a place that met the needs of a small group of artists who needed access to equipment and a venue to present concerts of experimental music.

The Tape Music Center quickly developed a unique philosophy and aesthetic mission. It was a place where artists could do things that they couldn't do in a normal venue or in an academic setting. The concerts were not really legal and sometimes they were picketed because of some part of the performance was unacceptable to the general public. For example, Robert Davis had a piece that consisted of four naked people on toilet seats--in 1961 that was considered totally outrageous.

In 1961 they had been given a mansion somewhere on Jones Street. It was going to be demolished in a year so they used it as a concert hall. There were about nine concerts the first year, mostly consisting of about a half hour of electronic music followed by works from other composers. Although composers such as Sender, Subotnick, Pauline Oliveros, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and light artist Anthony Martin were very prolific, there was a considerable amount of time experimenting with other modern composers' works that were not being recognized by academia or regular concert goers. Recent works that were being written by composers like Cage and Berio, were not only being rehearsed and performed, but were augmented by some movement, or an experimental light show.

The Tape Center sparked my interest because it was an open environment to experiment with new technologies, which in turn, spawned the creation and development of the buchla synthesizer. When The Tape Center was on Divisadero it shared the space and collaborated with The San Francisco Mime Troupe, KUSF and local pop artists. The Tape Center also thrived on this collaboration and combination of the different art forms and disciplines. It was open to all artists in the community. Consequently, it helped establish San Francisco as the birthplace of "Multi-Media" and the exploration of new technologies in the arts.

"It was about the freedom to experiment and about reaching an audience interested in what we were doing," said Morton Subotnick. Interest in the Tape Center ranged from the forefront of avant garde classical music to the pop groups of the sixties. The breaking of these boundaries had a profound effect on both genres.

Pauline Oliveros said, "The rock music scene was revving up then. I remember Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin visiting the Tape Center. Different musicians came through to check out the technology especially after Don Buchla introduced his Buchla Box (Synthesizer). Anthony Martin, who did our light shows, begin to work with the rock bands at the Fillmore Auditorium. The Trips Festival took the Tape Center works out into the music industry.

The Pirex Plate light shows of the '60s were created by Lee Remour but then shortly picked up by Tony Martin. The Pirex Plate Lights Shows are the classic multi-colored trippy-dippy light show. Tony Martin then did the light shows for the Mothers of Invention.

"Psychedelia opened up a lot. Boundaries became very fuzzy for awhile as the scene exploded and thousands of people began to inhabit the Haight-Ashbury district where the Tape Center was located. Mostly people were getting out of their heads with LSD etc.," Oliveros told me.

Artists at the Tape Center broke down disciplinary boundaries and normal administrative functionality. This produced a cross-pollinating ferment between audio and visual media. Ramon Sender's Desert Ambulance--for accordion, tape, slides, and film--and Morton Subotnick's Mandolin--for viola, tape, slides, and view-graph projection--are examples of this pioneering work in "mixed media." Or, what is later know as multimedia. Painters like Robert Laveen were doing real-time painting, which was later labeled "performance art." Ronnie Davis started the San Francisco Mime Troupe. Even when the music was somewhat traditional there was political and theatrical experimentation laid over the top.

San Francisco's diverse audience made it very easy to experiment both aurally and artistically, although there were a few minor protests about some of the content. Pauline Oliveros describes the audience as a collection of friends and acquaintances, but it also included many soon to be prominent members of the rock scene of the '60s. There was a close relationship between "hi art" and "low art"; or rather there were no boundaries between artistic disciplines.

Charles Boone wrote, "the Tape Music Center was proof that music here could be created completely outside academic and commercial circles. It demonstrated, too, that ambitious concepts and projects could be realized on a shoestring; that innovative music depended more on the vitality of the ideas than on big budgets and fancy tools."

Sources: Thirty Years of Non-Stop Flight: A Brief History of the Center for Contemporary Music David W. Bernstein

emails with Pauline Oliveros; phone conversations with Morton Subotnick