BLACKS AND LABOR: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(PC) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = arial light> <font color = maroon> <font size = 3>Unfinished History</font></font> </font>''' | |||

[[Image:Aframer1%24palace-staff-circa-1878.jpg]] | [[Image:Aframer1%24palace-staff-circa-1878.jpg]] | ||

Revision as of 23:38, 28 December 2008

Unfinished History

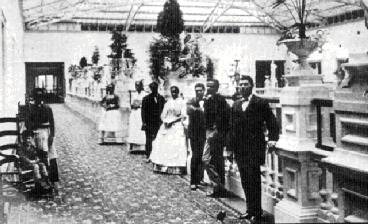

Black workers at the Palace Hotel, c. 1878. All blacks were fired in 1888 due to racist pressure on the Hotel.

Photo: Bancroft Library, Berkeley, CA

African-Americans began arriving in San Francisco with the first waves of prospectors heading to the gold fields. California became a no-slave territory by 1856, but blacks rarely achieved anything approaching social or political equality. The primary limitation to black achievement in San Francisco was the narrow range of jobs available, a reality which grew worse as white workers got organized in their own defense by the 1870s. A high percentage of Afro-San Franciscans were employed in the service economy as waiters, draymen, porters, maids, ship cooks, stewards, etc. (60% of the working males and 97% of the females). A number of early black settlers did quite well in easy money, boom-and-bust, open gambling and real estate markets of the city. In 1862, while the Civil War raged back east, blacks in San Francisco owned $300,000 in assets, much of it in real estate. Mammy Pleasant owned $30,000 in real estate in 1870, while a partner, Richard Barber reported $70,000 in holdings.

A success story was that of George Washington Dennis. Since he arrived in San Francisco before 1856, he was the property of his owner, who also happened to be his father. He made a deal: when he had earned $1,000 as a porter at the El Dorado (owned by his father) he could purchase his freedom. Within three months he had done so, and though as a black he couldn't testify in court or vote, he spoon purchased his mother's freedom as well. He unsuccessfully speculated in mining stocks, but he managed to open the Custom House Livery Stable at Sansome and Washington, and by 1867 he started the Cosmopolitan Coal and Wood Yard at 340 Broadway. By 1889 he had a fortune of $50,000.

The number of blacks in San Francisco never surpassed about 1,500 until after World War I (it was only about 4,000 by the onset of World War II at the end of 1941). Douglas Henry Daniels argues in his important work Pioneer Urbanites that there were such strong racial exclusions by the white unions and the practice of white businessmen, that there simply were few reliable jobs available to blacks, and virtually none outside of the preponderance of domestic help. The black newspaper The Elevator (1865-1898) railed vituperatively against the competition, Chinese and European immigrants, in 1865:

“We have enough, and more, of them here now, eating our substance, polluting the atmosphere with their filth, and the mind with their licentiousness.” The Elevator also advised avoiding the mistakes of the eastern states which erred by inviting “the discontented and vicious of all Europe to their shores.”

But The Elevator itself was forced to rely on white printers because the powerful Typographical Union forbade hiring experienced negroes or training colored apprentices. At least half a dozen colored printers were forced to work in other trades because of racist exclusion by the union. By 1913, W.E.B. Du Bois' NAACP publication, Crisis, reported that “white trade unions have held the negro down and out in San Francisco.”

The long and sordid history of white working-class racism helps contextualize the frequent use of blacks as strikebreakers in San Francisco. For example, in the hot summer of 1916, restaurant and kitchen workers were locked out by employers as part of the general campaign to break union power being pushed by the Chamber of Commerce (see Law & Order Committee). Restaurant and cafe managers declared an open shop policy and began hiring scabs, many black. In mid-July two black scab longshoremen were killed along the strike-bound waterfront. By the winter, most of the strikes had ended in victory for the unions, and black workers were again pounding the pavement in search of work.

When the Chamber of Commerce finally broke the longshoremen's strike in 1919, a more (racially) fluid waterfront labor market led to an influx of black workers, although they were required to work in segregated work gangs and weren't allowed to join the union. By the 1930s it was apparent that a rejuvenated workers movement depended on an alliance across the boundaries of decades-long racial enmity. The ILWU from its inception pursued a color-blind policy, although racial discrimination continued in other west coast ports long after the official integration of the ILWU. (The ILWU itself was rocked by charges of racism following the termination of 80-odd black “B-list” workers in 1963.)

--Chris Carlsson, 1994

This "Honey Bee" worked at the Hunter's Point Naval Shipyard in 1944.

Photo: African American Historical and Cultural Society, San Francisco, CA

Pioneer Urbanites book cover