WILLIAM RICHARDSON AND YERBA BUENA ORIGINS

Historical Essay

by K. Maldetto

William Richardson became the earliest Anglo inhabitant of Yerba Buena (early San Francisco's name) in 1822 when he jumped ship, beginning a long tradition of crews leaving for the city.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library, San Francisco, CA

From its very beginnings, San Francisco was unlike any other American city: the absence of established social conventions, the mad quest for gold, and a heterogeneous population coming from all parts of the globe, all contributed to a varied and lively urban scene unencumbered by social restraint. Starting in 1849, Mexicans, Chileans, French, Anglos, Germans, Chinese, Indians and countless others converged on the Peninsula in search of instant wealth. During the Spring and Summer they rushed to the Sierras, put their heads down and dug hard for gold; in the Fall and Winter they came back to the city to wait out the bad weather and make up for lost time (and homesickness) in the numerous restaurants, gamehouses, bars and brothels. These were seedy times and in the words of one observer named Hinton Helper San Francisco had the hands down monopoly on the best bad things:

I may not be a competent judge, but this much I will say, that I have never seen purer liquors, better cigars, finer tobacco, truer guns and pistols, larger dirks and bowie knives, and prettier courtesans, here in San Francisco, than in any other place I have ever visited; and it is my unbiased opinion that California can and does furnish the best bad things that are obtainable in America.

Appropriately enough, the future founder of the city, William A. Richardson, ended up living on the San Francisco peninsula because he had ... partied all night long at a fiesta being held at the Presidio ...

Captain William A. Richardson, founder of Yerba Buena, site of the future San Francisco, was born in London on August 27, 1795. At the age of 12, he began a career in the British Merchant Marine. He started as a cabin boy on ships making trips to the North Sea and South America and rapidly rose the ranks. By 1820, he was the first officer of the British ship Orion. After two years of sailing, mostly in the North Pacific, the Orion entered San Francisco Bay on August 2, 1822, in view of obtaining fresh meat and water for the long trip back home via Cape Horn.

Since Richardson spoke some Spanish, the Captain of the Orion, Mr. Barney, sent him ashore to explain the purpose of their visit to the Spanish authorities. Upon reaching the eastern shore of the peninsula, Richardson was accompanied by a squad of soldiers to the San Francisco Presidio. After promising Richardson the needed supplies, Ignacio Martinez, Commander of the Presidio, invited him to a fiesta that he was holding that very evening at the presidio. After introducing Richardson to his family and guests, mostly fellow officers and their families, Commander Martinez called for the fiesta to begin. Brandy and music poured into the room and the people performed the contradanza, jota, jarabe and other Spanish dances. In the course of the dances, the Englishman seemed to take a liking to one of his partners, Señorita Mara Antonia Martínez, eldest daughter of the Comandante. The feast was so much fun that Richardson did not head back to the Orion until dawn ...

Captain Barney not at all pleased with his first mates tardy return, and probably jealous he had not been invited to the fiesta, severely reprimanded Richardson. Then it is unknown whether Richardson was dismissed and sent ashore or whether he jumped ship. In any event, the Englishman arrived back at the presidio the same day and explained his situation to Comandante Martinez. The Comandante, probably more in tune with the potential vagaries of fiesta-making than stiff-lipped Captain Barney, proved understanding and allowed Richardson to stay with his family until another ship arrived or until he received permission to stay in California.

Smitten with the charms of Señorita Mara Antonia Martínez, Richardson quickly decided he wanted to stay in the area. Following the Comandante's advice, the Englishman headed for Monterey and on October 7 presented a petition to Governor Pablo Vicente de Sol asking for permission to settle in California. Governor Sol granted Richardson the privilege of becoming a resident on condition that he teach navigation and carpentry skills to the local youth. After receiving religious instruction, Richardson became a Roman Catholic in 1823, a necessary step in order to become a naturalized Mexican citizen, marry Mara Antonia Martínez and obtain a land grant. In 1825, after obtaining permission from Governor Arguello, Richardson and Maria Antonia married.

Richardson's arrival coincided with a time of great commercial and political change in California. In March of 1822, news arrived in Monterey that after ten years of struggle, the former colony of New Spain had finally emancipated itself and would now be known as Mexico. After 1822, Mexico implemented an important change in commercial policy by abrogating the Spanish law of forbidding trade with foreign vessels. Henceforth, foreign merchant vessels were allowed to anchor and trade at ports throughout California, provided captains first stopped at Monterey and paid anchorage fees and custom duties. This new commercial policy heralded the era of the "hide and tallow trade" lasting essentially the period of Mexican control over California (1822-1846).

The hide and tallow trade was based on the exchange of goods between the large ranches of California and merchant ships from Great Britain and New England. The British and North American ships anchored off the coast of California, from San Diego to San Francisco, and traded finished goods such as shoes, clothing and furniture for cowhides, tallow (beef or mutton fat), furs and food supplies. The tallow was sold in South America and New England for the manufacturing of candles and soap. The majority of the hides were taken to Boston and served as the raw supplies for the leather industry that flourished there. The ships would first anchor at Monterey to pay anchorage fees and custom duties—although smuggling was very common—and then proceed to towns up and down the coast. Once a ship reached a port, the ranchers and locals would come on board and pick out items they liked in exchange (1) for specified amounts of hide and tallow. There were no wharves for the ships to dock at any of the California ports, so all goods that were exchanged had to be transported by light boats.

The opening of San Francisco Bay for trade with foreign vessels proved beneficial to Richardson given his naval and language skills. Indeed, when the merchant ships entered San Francisco Bay, Richardson would often pilot them through the waters, oversee the transferring of goods and serve as translator. From 1822 to 1829, Richardson facilitated the hide and tallow trade in this manner. Through other seafaring activities, such as sounding the waters of the bay for depths, islands and shoals, the Englishman came to be known "Captain Richardson." Equipped with a rowboat and whaleboat, Captain Richardson also took charge of the transportation of goods and food supplies throughout the Bay Area which until then had been carried laboriously by oxcart.

In 1829, Richardson and his family moved to Mission San Gabriel (near present-day Los Angeles) where they remained for the next 6 years. This move proved beneficial to the Englishman in many ways, chief among which was his fortuitous encounter with the Governor of California, Jose Figueroa, who was at San Gabriel on an inspection trip in May of 1835. The Governor and Captain Richardson sympathized and during their talks they discussed several matters related to the distribution of land to settlers, the promotion of trade and more generally the colonization of Alta California. The Englishman had a strong interest in these issues since he had long wanted to obtain a tract of land immediately north of the entrance to San Francisco Bay, extending from Sausalito to the Bolinas Lagoon. In fact, three months prior to meeting the Governor he had submitted a petition to obtain the aforementioned tract of land. In addition, the Englishman asked for a small residential lot at Yerba Buena Cove on San Francisco Bay.

William Richardson's Petition:

W. A. Richardson, a native of Great Britain and a resident of this province, hereby respectfully represents that he arrived at this port of San Francisco on the second day of August last, as a mate of a British whaleship, and it being my intention to remain permanently and become domiciled in this Province at some place with suitable climate, I most humbly pray your Honor to grant me this privilege and favor.

While talking with Governor Figueroa, Richardson mentioned his application for a lot at Yerba Buena as well as his recommendation that the Government of Mexico establish a customhouse and a commercial town at Yerba Buena both of which were turned down. Governor Figueroa, however, seemed very interested in Richardson's plans for Yerba Buena and asked him to make a sketch of the proposed pueblo. According to later testimony by Richardson the Governor "requested me to come to Yerba Buena to establish me as Captain of the Port of San Francisco, as he had seen a communication, written by me in 1828, respecting the anchorage at Yerba Buena, and he wished to lay off a small settlement for the convenience of Public offices at the anchorage ... He gave me verbal orders to come to Yerba Buena and await his orders." Once appointed Captain of the port of San Francisco, Richardson headed up to Yerba Buena Cove with his family. On June 25, 1835, he chose a site on a rise above the beach and set up a temporary dwelling made from a ships sail and four redwood posts. This was the first residence at Yerba Buena Cove, site of the future city of San Francisco. Mariana Richardson, daughter of the Captain, was nine years old when they arrived at Yerba Buena Cove and later recalled:

"Father, immediately upon arriving at Yerba Buena, pitched his tent and made us as comfortable as possible. Yerba Buena at that time was nothing but sand dunes, covered with shrubbery and trees. Most of the trees were what we call the Christmas berry. Wild animals were very numerous, such as bears, wolves, coyotes. I remember before my father constructed his adobe house, while we were still occupying the tent, one night a bear put his paw under the tent and carried off a screeching rooster."

Official confirmation of the establishment of the pueblo of Yerba Buena and of Richardson's land title came in October 1835. During a testimony in court about the assignment of land grants, Richardson described (2) Yerba Buena and how it came to be established. With confirmation of his land title, Richardson quickly resumed his former trading and seafaring activities. He reactivated two waterlogged ships, the San Francisco and the Guadalupe, and once again began transporting goods and people around the Bay. In 1836, a second settler, an American named Jacob Leese, established himself at Yerba Buena. From 1836 to 1838, date at which Leese left, the two were in partnership and cooperated in providing foreign ships with produce. During those years, more than 20 ships a year anchored at the Bay and brought in finished goods in exchange for hide, tallow and fresh produce. As Captain of the Port, it was also Richardson's duty to board all the ships that entered the Bay, check their papers and record the amount of goods they brought back with them. Richardson's maritime report of 1837 provides a detailed account of the countries San Francisco Bay traded with and of the type of goods that were being bartered.

Port of San Francisco, Maritime Report for 1837:

25 ships entered the port: 10 from the United States, 5 from Mexico, 5 from the United Kingdom, 2 from Russia, 2 from Ecuador and 1 from Hawaii.

California products exported: 15,928 hides; 12,494 cow horns; 302,654 pounds of suet (interior beef tallow); 13,038 pounds of lard; 70,714 pounds of dried meat; 21,714 pounds of potatoes; 14,510 pounds of flour; 11,364 pounds of wool; 2,579 pounds of otter pelts; 270 deerskins; 400 calabashes; 54 live cattle; 100 sheep; wheat valued at $4,792; seeds worth $348; maize worth $198; oats worth $35 and $11 worth of beans.

Total declared value of goods exported from San Francisco Bay in 1837: $75,711

From: William A. Richardson, Salidas de buques del puerto de San Francisco, 1837-38.)

Richardson remained at Yerba Buena until June of 1841 date at which he moved to his ranch in Sausalito across the entrance to the Bay. He found that he could perform his duties as captain of the port just as easily from Sausalito as from Yerba Buena while having much more space and resources for his family. He sold his adobe house and two lots at Yerba Buena for $5,000, the first in a long series of bad business decisions which would eventually culminate in financial ruin. Henceforth, the Captain had only very limited influence on developments at Yerba Buena, or San Francisco as it was named after January 1847. His son Stephen explained his decision to move to Sausalito thus:

"Having laid the foundation stones of a city and watched its progress long enough to know with certainty that it would grow, my father turned his back on it. Had he waited a few years longer till the great gold rush began, with a probable acquisition of land and water rights, his wealth would doubtless have been enormous--large enough to withstand the mishaps that wrecked his fortune in his old age ... Indeed, my father believed that two cities would spring up on each side of the Golden Gate, and he preferred to cast his lot where owned everything."

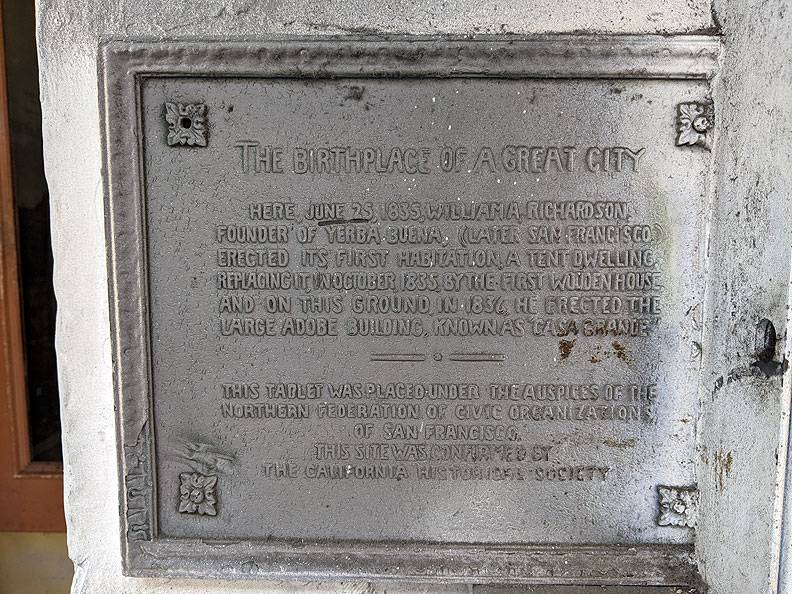

A few bad investments, punishment from Lady Fortuna who sank Richardson's three ocean-going ships in the space of six months in 1853, the mortgaging of his huge Sausalito ranch and sound financial advice from a money-hungry real-estate agent took care of everything and in 1856, spiritually and materially broken down, William A. Richardson died leaving San Francisco Bay just as he had come to it: landless. Aside from Richardson Bay and Richardson Avenue in Sausalito, the sole memorial to Richardson's influence on the history of the region is a modest bronze plaque at 823 Grant Avenue in today's Chinatown which reads:

"The birthplace of a great city. Here, June 25, 1835, William A. Richardson, founder of Yerba Buena, (later San Francisco,) erected its first habitation, a tent dwelling, replacing it in October, 1835, by the first wooden house, and on this ground, in 1836, he erected the large adobe building, known as 'Casa Grande.' "

Early plaque commemorating the location on Grant near Clay (today) where Richardson built his "Casa Grande," the first house on the slopes above Yerba Buena Cove.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The location, 823 Grant Street in Chinatown, where the plaque is located. Not easy to find!

Photo: Chris Carlsson

1. There was very little use of currency and most trading was in the form of barter. Apparently, the missionaries fear of being taxed from the government, if they accumulated wealth, also contributed to the lack of currency circulation in California. Whenever they could, the missionaries chose merchandise over coin. As a result, hides became the most common form of currency. They were know as "leather dollars" or "California bank notes" and were generally valued from $1 to $2 each. Tallow could also be used as currency and was typically valued at 6 to 8 cents per pound.

2. When I came to reside at Yerba Buena there were no inhabitants there; there had been no lands or lots granted to any individuals at that time, to my knowledge. In the early part of October 1835, I received a one hundred vara [275 feet] lot in Yerba Buena, situated in what is now Dupont Street [Grant Avenue], on the south-west side of that street ... In 1835, in the month of October, the Alcalde of the Mission of San Francisco de Asis, Don Francisco de Haro, received orders from the Political Government to lay off a small town at the Yerba Buena [Cove] for the convenience of locating public offices at the Port of San Francisco, for the convenience of shipping, as the place called Yerba Buena was the general anchorage for shipping at that time. The same orders directed me to assist de Haro in doing it, and the orders also directed de Haro to give me a one vara lot, and to reserve two hundred varas [550 feet] all along the beach for government buildings, and to make a plan of the place selected and measure off for the town.

Further Reading:

Barker, Malcolm; San Francisco Memoirs, 1835-1851, Eyewitness Accounts of the Birth of a City; Londonborn Publications, 1994.

Bean, Walton and Rawls, James; California: An Interpretive History; 5th ed., McGraw-Hill, 1988.

Lewis, Oscar, San Francisco; Mission to Metropolis; Howell-North Books, Berkeley, 1966.

Miller, Robert Ryal; Captain Richardson, Mariner, Ranchero, and Founder of San Francisco; La Loma Press, 1995.

Wollenberg, Charles; Perspectives in Bay Area History; UC Berkeley Press, 1984.