The Birth of Carnaval on the Streets of San Francisco

"I was there..."

by Willy Lizárraga

Sir Lawrence, Adela Chu, and others at the first Carnaval in Precita Park, 1979.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

The Origin of the Origin

On February 25th, 1979, a windy, cold and rainy Sunday in San Francisco, about three hundred drummers and dancers, dressed in multifarious colors and shapes, paraded around Precita Park in the Mission District. Perhaps for the uninformed passerby, it all seemed like a crazy, “hippie,” let’s-dance-half-naked-in-the-park event. For the revelers, however, it was the culmination of many months of planning and rehearsing carnival in a city that until then didn’t have one—and now can boast of hosting, if not the biggest, certainly the most diverse carnival parade in the entire country, if not the world.

How did it all come about? Who made it happen? Why did it take place in the Mission District to begin with? One question leads to another and all of them point to Adela Chu, who can easily trace her carnival dream to her childhood in the city of Colón, Panama.

“I was three,” recalls Adela, “it was carnaval time, and my mom was sewing costumes, like every year. She was sewing these cute pink tutus with a big red valentine over the bodice, and I wanted to wear one sooooo badly. But I was told I was too young to be in carnaval. I think at that moment my carnaval dream began. And I took that dream with me wherever I went. That’s why, many years later, when I lived in San Francisco, any chance I had to do carnaval, I’d go for it. People just loved it too, which was probably the reason why I thought San Francisco would be the perfect place to start a carnaval tradition. The spirit was there, the drummers, the dancers. And I knew lots of them because I was a samba instructor. I guess you can say that teaching samba was my way of keeping my carnaval dream alive.”

Adela Chu in her silver headdress, 1979.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

Listen to Willy Lizárraga tell the story in a 2010 interview:

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/HistoryOfTheMissionsCarnaval" width="500" height="40" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Keeping her dream alive, or at least trying to do so, Adela staged her first carnaval in San Francisco at the Masonic Temple, in 1976. The same year, with Ana Halprin’s Dance Company, she organized a carnaval performance at the 24th Street BART Station. And the following year, with Chalo Eduardo’s help, she took carnaval to Ocean Beach where it all became a kind of Burning Man event.

Then, in 1978, Adela went to Brazil. When she came back, “It was like I had no choice. A city like San Francisco without a carnaval didn’t make any sense to me.”

For all practical purposes, then, let’s say the story of carnaval in San Francisco began when Cristina de Oliveira, a very dear friend and ex-samba student of Adela, invited her to spend carnaval in Rio. In fact, we might as well say that the history of the San Francisco Carnaval springs from Cristina’s invitation letter, which Adela, after all these years, still knows by heart, grammatical mistakes included. And every time she says it out loud, it always feels like the beginning of the most fantastic fairy tale.

“Dear Adela, carnaval going to happen in the end of the month. So you can came any time. Because me, my friends, the Sun and Yemanja are here waiting for you. P.S. Came quickly, everybody waiting.”

From Dream to Reality and Vice-versa

“I first thought Adela was crazy, man. I mean there are hundred, thousands of years of dancing tradition in Brazil, Panama, Trinidad and all those carnaval countries, you know what I mean. You can’t just create carnaval from one day to the next. Besides, one thing is to dance in a class setting, but it’s something else to take to the streets and make it real. And I don’t mean to put anybody down. I mean I was Adela’s drummer in all her samba classes, so I knew she had the best intentions in the world, and her students had the biggest hearts, but they really couldn’t samba. And they had no idea what carnaval is all about. Maybe that’s why what Adela did is so amazing, man. Carnaval in San Francisco? In February? Give me a break, man!”

Orlando Hernández was, indeed, Adela Chu’s most faithful drummer and probably not the only one who thought she was a bit unrealistic in her carnival expectations. As a drummer, however, he had to be aware, although he didn’t mention it, that the drumming circles in the different parks in the San Francisco Bay Area was the best training ground for anyone wanting to throw a carnival parade on the streets. In the same vein, carnival had been steadily cooking in the different dance studios in the late seventies and was ready to come out of the closet.

So as rehearsals began under Adela’s supervision, she wasn’t creating or importing an event as much as simply giving San Francisco’s drummers and dancers a chance to come together in a slightly more focused and organized fashion. That was and is her gift to San Francisco. The rest resembles a tapestry of the most diverse carnival dreams and traditions that, along with Adela’s, had begun to feel quite at home in the Bay Area.

If one could say, then, that with Adela came the African-flavored carnaval from Colón, Panama, as well as the all-encompassing Brazilian inspiration, in a similar fashion, with Marcus Gordon, Adela’s main collaborator and, afterwards, San Francisco’s carnaval artistic director for fifteen years, came the West Indies Carnival from Harlem. To which one must add the names of Jose Lorenzo, Marlene Rosa Lima, Bira Almeida, Chalo Eduardo, Claudio Araujo and so many other ebullient and dedicated dancers and musicians without whom carnival might have happened but would have never established such deep roots.

Marcus Gordon, who brought the drummers to the first Carnaval and played a major role in organizing it in the following years.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

In this light, when we say that on the last Sunday of February of 1979 Adela Chu gave birth to the San Francisco Carnaval in Precita Park, perhaps all we say is that she provided a face, a location and a pathos to an array of historical agents, all of them coinciding in a city that by then was, to use Frida Kahlo’s favorite way of describing San Francisco, “the city of the world.” And one must include even the weather among all those ingredients contributing to the birth of carnival. For that day, typical of winter (and often summer) in this city, it looked inhospitably overcast. The sun came out, however, as the drummers and dancers were about to go around the park. And when they finished, the rain came down with a vengeance as if to remind them that, despite the fact that they had successfully staged the first carnival in the Mission, it was still a long way from finding a home in the form of a more suitable location in time and space.

El Barrio & The Unexpected Road Ahead

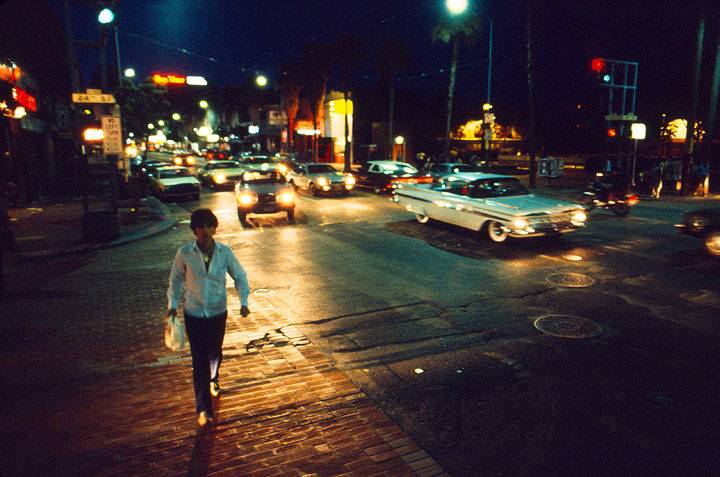

Speaking of time and space, in the late seventies, the Mission was a funky, predominantly Latino neighborhood, experiencing a gradual transformation into an alternative bohemian hangout. A few cafes had just opened. There were no fancy restaurants. Rainbow’s organic produce store had opened next to the Roxie Cinema, which, by the way, was visibly struggling to establish itself as an art-film house and forget its porno movie house past. The most incontestable signs of change, however, came from the defiantly loud and tough presence of dykes on bikes along Valencia Street and from the punks, lying on the sidewalks around 16th Street like post-modern iguanas with their red, purple and green hair, terrible skin and ominous breath.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

In the opposite corner of this social and economic struggle, representing the past, were the low riders (pit bulls included, of course), a vanishing barrio aristocracy living their last days as kings of the Mission, and who on Sundays with the help of fellow low riders from all over the Bay Area would cruise Mission Street and, literally, transform it into a bumper-to-bumper car and fashion parade: the rucas in full make-up and tight, skimpy dresses, the vatos showing off the creases on their pressed zoot suits, and their cars, yes, above all their cars turned into rolling baroque art installations.

The cops, needless to say, did not view these pachuco parades with kind eyes. In fact, they figured it was either them or us.

Mission and 24th during the Low Rider era, c. 1980.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

Meanwhile the Filipinos, the other ethnic group with extensive roots in the barrio, were beginning to move out to exotic locations like Serramonte and Daly City. And, yes, they also drove big, imposing, spiffed up cars, preferably Camaros and Trans Ams with tons of chrome and roaring engines, only they drove high, not low. They liked their cars to look as if they were on stilts. They also liked to sport formidable mullets, often called “Manila Falls.”

Music wise, disco was big, so was rock, funk and punk. Salsa was reaching its most inspired moment. The Vietnam War was beginning to fade from memory and Nicaragua’s Sandinistas were the revolutionaries of the day. And all of these changes were beginning to be reflected and portrayed on murals and placas while Adela Chu, Pam Minor and Elaine Cohen planned Carnaval inside Café Babar on Guerrero Street.

“Yes, yes,” Adela laughs and talks at the same time, “Café Babar was probably the closest thing to our headquarters. It’s so funny, so amazing, really, how we put the whole thing together in that cafe. I don’t think we ever had one single official meeting, you know. Well, we talked on the phone a lot too. If I’d had to endure, though, endless meetings and coordinate committees and that kind of stuff, I swear I would’ve never done it.”

Nowadays Adela Chu lives in Oahu, Hawaii. Her African-Chinese ethnic background has acquired a majestic Polynesian flair. The thin, wiry, long-legged and flat-chested twenty-something dancer has grown into a bodacious, round and solid, Hawaiian beauty. Perhaps a healthy tinge of nostalgia for her California days infuses her memories. Aside from that, there’s no affectation when she talks about her time in San Francisco, or about being the creator of one of San Francisco’s most colorful and representative events on par with the Chinese New Year’s Parade and the Gay Pride Parade.

Yes, San Francisco in the late seventies: writers wrote texts, performance art was hot, life was a succession of happenings, fusion was the key word when musicians jammed together, and “minorities,” including those fighting for ethnic, gender or sexual orientation equality were beginning to taste the fruits of their long and often cruel struggle, a struggle that precisely three months before Carnaval suffered one of its most tragic blows with the assassination of Mayor Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk. And is if to make things even more unfathomably morbid, the Jonestown massacre in Guyana, where hundreds of Bay Area residents would die, would take place during the same week of November 1978.

The show had to go on, though. Adela Chu continued rehearsals and kept recruiting all the help she could get. And the closer it got to Carnaval day, the more she realized she needed someone with real expertise in the tumultuous art of dancing and partying on the streets, which took her to Jose Lorenzo, at the time the most visible and talented Brazilian musician, dancer and carnival entrepreneur in the Bay Area.

“Then, a few weeks before carnaval, Jose Lorenzo backed out, can you believe it? He told me he’d found another gig, a paid gig, and off he went. He even took with him my best drummers and dancers.”

At which point, the fortuitous appearance of Marcus Gordon turned a dire impasse into a winning carnaval equation, all thanks to Beatriz Ross who gave Adela Chu his telephone number.

“What can I tell you? I was desperate and Marcus really came through. I mean he literally bailed me out.”

The Tall Black Man in White

Marcus Gordon not only came through with impeccable timing, but also had the perfect credentials to turn Adela’s carnaval dream into a crisp and palpable reality. He was a real conguero de fundamento in the Yoruba tradition with an easy going personality, a sharp sense of humor and well groomed organizational skills polished throughout many years of teaching percussion. More importantly, he brought along with him the best drummers in the Bay Area.

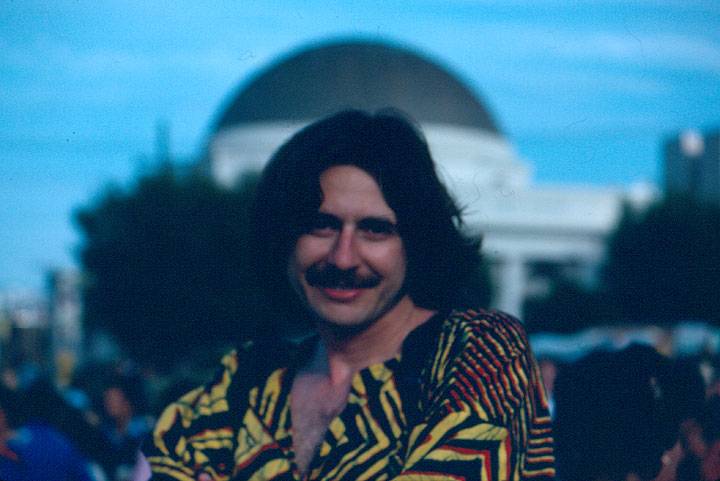

Marcus Gordon, 1979.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

“Well, at the time, all the conga players, we all knew each other,” Marcus Gordon recalls. “I knew John Santos, José Flores, Yele and Teddy Strong from Dolores Park. Aquatic Park was also popular but that was more tree-shade playing. The good players gathered in Sproul Plaza in Berkeley, which is where I met incredible people like Babatunde Lea, Tobajee, Malonga, Bill Summers and so many others. There was a huge drumming culture in the Bay Area. It had no reason to envy any other city in the country, including New York, which is where I came from in ‘69. If you were a drummer in the seventies, the San Francisco Bay Area was the place to be.

“And I think I was teaching drumming at Berkeley High and Laney College when Adela Chu invited me to join her. With Boby Céspedes and other musicians, we had a group called Coco Santo. It was essentially an Afro-Cuban Santeria ensemble, but we could also play guaguancó and comparsa. We could play anything, really. With this group, my drumming students, fellow drummers, John Santos’ and José Flores’ drumming students, Chalo’s and Adela’s dancers, that’s how we put together carnaval in Precita Park.”

Ironically, because Marcus was a Yoruba priest novice, he couldn’t wear a costume. Or maybe it is more appropriate to say he could only wear one very special costume. That is the reason why in all the pictures from the first and second Carnaval, Marcus is all in white, running around like a field general, ubiquitous and imposing, wearing attire that probably suited his Carnaval savior role better than any other costume he could have chosen.

Bring Back The Sun Or Warming Up For Carnaval

Music and dance are key ingredients in carnival, but without costumes, carnival is not carnival. And for costumes, in the late seventies, you went to the Costume Bank in the Western Addition or to Pam Minor, who later became director of the Costume Bank because of Carnaval.

Pam Minor preparing for the first Carnaval.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

“I remember we got five dollars from all the participants,” Pam Minor remembers, “and with that money we went to the Costume Bank to make our own costumes, all at the last minute. When else? Oh, yeah, we had a few late nights in the Bank, but we sewed it all ourselves, including the drummers, who at first were kind of ‘me, sewing?’ But then they all got into it thanks to Conga Phil who set the example. Anyway, for the first carnaval, I was in charge of costumes, public relations (it sounds so glamorous, ah) and getting the city permit. And all because of a winter solstice happening I organized a couple months earlier. I called it The Bring Back The Sun Parade.”

Pam Minor remembers calling up Adela Chu on the phone the morning of the winter solstice parade, “and actually waking her up because the drums were already going and I needed all the friends and dancers I could get a hold of. So I made sure Adela heard the drums on the phone. ’Cause I knew that would get her out of bed immediately. Don’t ask me though how we ended up with a bunch of drummers,” Pam Minor becomes silent as if trying to trick her memory into remembering. “That’s a big hole in my story. But we had them and we went around the block twice, I think.

“This may sound weird but anyway, that year we had a very cold and dark winter. So one morning, I had the realization that it was up to my friends and I to bring back the sun. Just like it sounds. Crazy, ah? Sometimes you just gotta do what you gotta do. So I told my friends, hey, listen, if we don’t do it… Well, the morning of the winter solstice I had an itinerary for the parade and a police permit. Which is why Adela trusted me with the city permit business for carnaval, since I had all this experience, right?”

Carnaval, Carnaval

Pam Minor did obtain the police permit for carnaval, but only for parading on the sidewalks, which might explain why the parade took place mainly inside the park, on the grass. And as befitted a carnaval birth, the excitement as well as a sense of not knowing what to expect united drummers and dancers as they gathered in the park.

Crowd at west end of Precita Park, Marcus Gordon in white in middle.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

There were no high expectations, for sure. There were no floats either. Instead, there were these gigantic masks made of papier-mâché, provided by the Mission Cultural Center, which added the only larger-than-life touch to the event, aside from the participant’s irrepressible enthusiasm growing exponentially as the group got larger and larger. So, by the time Jose Flores’ group Los Dandies, wearing these clownish pachuco outfits with bowler hats, came drumming down the hill to join Marcus Gordon’s drummers in red and white, the multicolored Rainbow Comparsa, the green and outlandish Money Comparsa led by Margaret de Jesus, the Tribu dos Carajas in red, the Susubaes wearing bird masks and the Yemanja Comparsa in classic white, blue and silver, and Sir Lawrence Washington, wearing a grand marshal outfit of sorts, began to lead the parade, you could say that at that moment there was no turning back. Carnaval had been born in the Mission District.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

Sir Lawrence leading the way.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

Recalling this and many other carnaval parades in which he played the grand marshal role, Sir Lawrence Washington explains:

“I used to take Adela’s samba classes in the Mission. I was a dancer and a performer myself, which is probably why Adela asked me to lead the parade. Well, also because I am very tall and easy to spot. In any case, I was used to doing crazy things on the streets of San Francisco. My wife Genevieve and I had group called ART, the America Revolving Theater. And we would call all our friends and dancers and stage these massive happenings all over the city. Well, no wonder I was chosen to lead the carnaval. And I knew we couldn’t compete with Brazil or any of the big carnival countries, you know, but at the same time, we had an honest desire to have our own carnival. So, I just tried to embody the local carnival spirit. That was my job. And one of my biggest thrills was to overhear all these kids screaming at me as I marched along: Wow, man, I want to be like you. What do you have to do to be in front of the parade?”

If one could say that Sir Lawrence’s royal presence was the closest thing to a carnival king presiding over the celebration, no one but Adela could play the queen. Fittingly, she and Pam Minor had worked out a Queen of Outer Space costume, all shiny with silver reflections and a bird-inspired headdress and a glittery silver cape, which Adela wore on top of a golden leotard. She knew this was her moment to shine and guide and make everybody at home celebrating life in all its ephemeral tragic and comic beauty because that’s what carnaval is all about.

From Dream to Reality & From Reality to More Reality

“One thing people forget when talking about an event, especially a historical event, is the context. And the San Francisco Carnaval didn’t come out of the blue. I mean, sure it was possible because of Adela Chu’s and Marcus Gordon’s effort, but the huge number of people that volunteered and participated, the ones who really made carnaval possible were here all along and they were greatly helped by almost a decade of subsidy for the arts.”

Carol Deutch in the middle.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

This is Carole Deutch, who back in 1979 was director of the Precita Park Community Center.

“At the federal level you had CETA. Then, at the state level, you had the California Arts Council, which thanks to artists and activists like Peter Coyote, Francis Coppola and Luis Valdez, to name a few, funded all kinds of art projects and individual artists. At the local level, you had the San Francisco Hotel Fund. And then, you had people like us, at the time working in the Precita Valley Community Center where we had art classes, mural classes, dance classes, drumming classes. That’s why when Adela and Marcus came to me to ask permission to use the gym for rehearsals, we not only welcomed them with open arms we joined in and gave it all to make it happen. Maybe all I’m trying to say is that carnaval couldn’t have chosen a better time or a better place to be born.”

Carole Deutch was, in effect, a privileged witness and helper in Carnaval’s birth. She was also so impressed and excited by what she saw that she essentially took charge of the newly formed carnaval committee to prepare for next year’s parade. The original committee also included, by the way, Adela Chu, Marcus Gordon, Pam Minor, Sir Lawrence Washington, Lou De Matteis and John Santos, who at the time taught percussion in the Precita Cultural Center. And taking into consideration the first carnaval’s resounding success amidst the most inhospitable weather conditions, the committee wisely decided to move carnaval to April 13th. As for the parade route, they arrived to the conclusion that it was time to take over Mission Street.

Mission and 19th from rooftop, 1980.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

For the second Carnaval, then, the different comparsas, musicians and floats would gather around Capp Street and 26th Street. From there, they were supposes to make their way through Mission Street, turned on 19th Street and finish at Dolores Park, where they had prepared a stage for an afternoon concert. The permit the committee had obtained, however, allowed them the use of only half of Mission Street. The other half was to remain free for normal traffic. As the parade marched along Mission Street, however, and people spontaneously joined in, it grew to such an extent that traffic came to a halt and there was nothing the police or the dancers could do.

“I guess word had spread around,” says Rachel Ross, who played the MC at the carnaval stage in Dolores Park. “Friends had brought friends and these friends had brought more friends and it was just a lot of people. I don’t think any of us expected such a turnout.”

At one point then, the low-riders, accustomed to cruising and ruling Mission Street, took charge and led the parade safely to Dolores Park.

Lou Dematteis, official carnaval photographer, has something crucial to say about this moment in San Francisco’s history:

“Well, the whole thing was just unreal, from the start. At ten o’clock in the morning, for example, when we told people to gather, there was hardly anybody there. By eleven, we were no more than the same people who did the first carnaval in Precita Park. So, I thought, well, it’s gonna be a small one but at least there’s gonna be one. At noon, though, when the parade was scheduled to start, all these people showed up I don’t from where. And as we paraded along Mission Street, more and more people would join in. What can I tell you? It was just one of those moments when I felt so lucky to be part of a thing like that. I mean, to witness 19th Street and Dolores Park covered with people, all of them singing and dancing. To experience such a spontaneous explosion of true carnaval spirit in a city that until then had never had one. That was the moment, I’d say, if there was ever a doubt that carnaval would take root in San Francisco, that was it. Carnaval was here to stay because the people of San Francisco had massively decided that this was the case.”

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

Dolores Park from 19th Street, 1980.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

Lou DeMatteis, 1980, Dolores Park.

The Artist and the Committee

Once again, though, victim of its own success, Carnaval had to look for a more suitable location. The Dolores Park neighbors had been overwhelmed by the amount of people and they were not going to allow carnaval to take place in their vicinity again. Faced with that challenge, the committee fractured into two apparently irreconcilable camps: the ones who wanted to take carnaval to the Civic Center and the ones who believed that it belonged in the Mission and shouldn’t be taken away.

Those who favored the Civic Center acknowledged that the proposed location lacked the cozy, barrio flavor so much a part of Carnaval’s identity. Space-wise, however, they claimed the Civic Center was a practical and intelligent solution. Also, it was a move that could help Carnaval become a truly city affair, a celebration that belonged to San Francisco as a whole and not only to a neighborhood. Despite its cold, grandiose and impersonal architecture, despite the long way for the parade to go, they believed the Civic Center provided a reasonable house for Carnaval. And they won.

Grove and McAllister, 1981.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

For the fourth year, the committee also decided that Carnaval would go back to the Civic Center. Heartbroken, Adela quit the Carnaval Committee. This time, she did not want to dance or parade with any group. For her, taking Carnaval away from the Mission was a betrayal of her dream. Carnaval had been her gift to the Mission and she wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I went into mourning, inconsolably,” Adela recalls. “I did participate, though, but in a very private, clandestine way. I mean, I didn’t tell anybody. I dressed as a blue mermaid with a big, fat blue tear dropping from my right eye, and went marching along the parade all by myself. I didn’t make it to the Civic Center. Then, a few months later, I took off to Amsterdam to play with a salsa band, and life just took me away from the Bay Area.”

Adela Chu, still laughing in 1981.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

As for the rest of the committee members, with the sole exception of Marcus Gordon, they all quit after the fourth carnaval, overwhelmed by the demands of time and dedication and lack of monetary incentive. Little did they know that carnaval would become a full-fledged corporate sponsored event and that the heart-wrenching struggle between the Mission and the Civic Center would remain a constant up until 2002 when the Mission would finally win.

Epilogue

Interestingly enough, Adela Chu and Marcus Gordon were not the first ones to stage a carnival parade in San Francisco. Two years before, Connie Williams, native of Trinidad and long-time San Francisco resident, had staged a Caribbean inspired carnival parade in the Western Addition. The fact that it didn’t take root, however, doesn’t mean that she shouldn’t be honored and remembered as a carnaval pioneer in San Francisco.

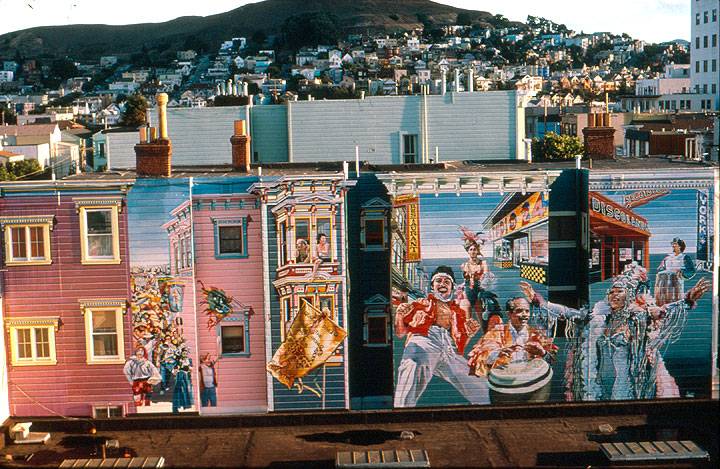

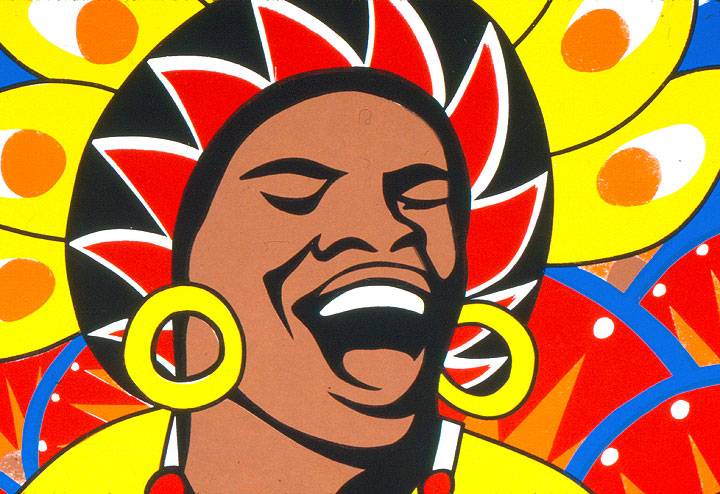

Michael Rios' mural, Los Congueros Cubanos.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

In the same vein, we should also remember Michael Rios’ mural Los Congueros Cubanos, the first mural in the city about the Mission carnaval. And although it doesn’t exist any more and very few people even remember it, it began an illustrious tradition that now includes iconic murals like Daniel Galvez’ “Carnaval” on the corner of 24th and South Van Ness (whose images are based, by the way, on photographs taken by Lou Dematteis), and the “Carnaval” mural on Harrison and 19th Street, designed and painted by Emmanuel Montoya, Josh Sarantitis and Carlos Loarca.

Daniel Galvez's mural "Carnaval" at 24th and South Van Ness.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

After repainting in 2014.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

There were also posters that came with carnaval, posters designed and printed by Nancy Hom, local artist and founding member of the Kearney Street Workshop in Chinatown.

Carnaval poster by Nancy Hom.

Photo © Lou DeMatteis

And, finally, going back one more time to the first carnaval in the Mission, going back, in fact, to Fat Tuesday, February 27, 1979, on that day, Adela led a small parade of dancers and drummer for a few blocks along the San Francisco waterfront to throw a dead sardine into the bay because, as she says:

“Everything comes from the ocean and must go back to it. And in Panama, where I come from, on Fat Tuesday es el entierro de la sardina. And if you don’t return the sardine to the sea, carnaval doesn’t come back. And I wasn’t going to take any chances. So, with all the dancers and drummers I could gather, we paraded along the bay on a cold and miserably rainy day. And everybody was freezing and tired and wet and mad at me and thought I was insane to do all this for a stupid, dead sardine.”