THE EARLY BIRD GETS THE OILY BIRD

"I was there..."

by Raymond C. Balter, reprinted from November 1994 issue of Terrain, magazine of the Berkeley Ecology Center

Volunteers working to sop up the oil in the San Francisco Bay in 1971.

Photo: Jonathan S. Blair

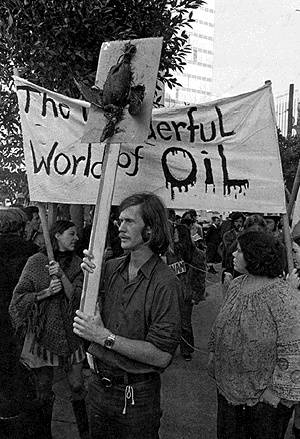

1971 demonstration against an oil spill.

Photo: Howard Harrison

A FIRST-HAND ACCOUNT OF THE VOLUNTEER BIRD CLEANING EFFORTS AFTER THE 1971 STANDARD OIL SPILL IN SAN FRANCISCO BAY

In the aftermath of the collision of the Oregon Standard and the Arizona Standard under the Golden Gate Bridge in January 1971, a newly-aware public responded to the disaster by volunteering in record numbers to assist with cleanup. Dozens of these volunteers worked at the Richmond Bird Care Center, cleaning sludge off injured seabirds. Despite active hostility from the Standard Oil corporation, volunteers were instrumental in mitigating the immense damage to the environment of the Bay, the Gulf of the Farallones, and the animals that lived there. Following is an excerpt of Raymond R. Balter's written testimony to the Congressional committee investigating the spill.

Richmond Bird Care Center was opened just after 8 am January 19, 1971. It was opened originally as an Emergency Cleaning Center, along with at least thirty similar operations during the night of the 18th and subsequently as the oil moved along the beaches and coastline.

It is not clear who had the idea of risking University of California property for this purpose, nor who selected the site for the treatment and care of oil-soaked birds. Like so many other responses in the early moments of a crisis, the facility almost seemed to "just happen." Several people placed calls to UC personnel during the evening of January 18, several originating from Berkeley Ecology Action and from the Ecology Center. Larry Schmelzer of UC apparently told Marc Monahan of the Ecology Center that the premises of the old Ford Motor Company facility in Richmond would be available for use. Greg Voelm of Ecology Action, who was working at the Center then, immediately began to plan and organize people and materials for the next day and arrived with Dr. Bruce Feldman, a veterinarian, and a crew of five or six at just after 9 the next morning. After some hassle with the guard at the gate, which was solved by the arrival of Schmelzer and Jack Godwin from UC Berkeley, this small force of people began to move pallets of paper and other supplies to create room for the unknown numbers of birds about to be delivered to their door.

The media had been alerted to the availability of this facility and they responded through the night and during the early morning hours, particularly KSAN radio in San Francisco. Supplies and people began to arrive almost as soon as the building was opened and very shortly people had to be assigned to the gate and parking area to keep order. Others were instructed to contact volunteers and still others to communicate with the information centers such as Ecology Center and Ecology Action in Berkeley, and the San Francisco Switchboard and KSAN Radio in San Francisco. Hundreds of spotters were dispatched during the day to slicked beaches or to coastal areas not yet examined for oil.

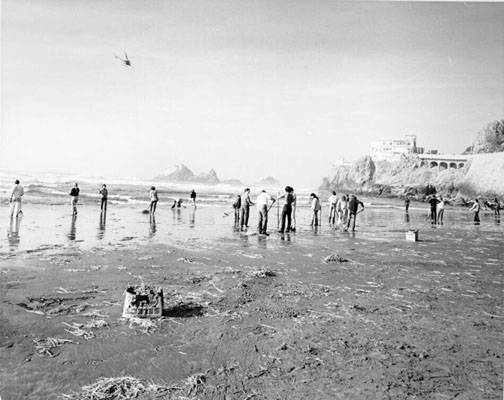

Ocean Beach oil spill cleanup, 1971.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Somewhere between 150 and 250 people performed various functions during the first day--before the birds arrived--without training in either warehouse management or bird care; somehow they moved things and organized equipment for efficient use in the hours and days that followed. There was, in the words of an early coordinator, "an incredible amount of activity and cooperative effort" during this time of waiting.

One area, perhaps 200 feet long and twelve or fifteen feet wide, was cleared of stored materials and the floor covered with sand. Thirty to forty long tables were borrowed from UC and installed in this long narrow space that was to become first the cleaning area and then the Intensive Care Unit. Later, part of this area was to become several small swimming pools for partially recovered birds.

Other crews rearranged pallets of paper to enclose an office and a kitchen area. Later that night still other areas were designated as sleeping quarters.

At this point, Greg Voelm, the only individual with any bird cleaning experience (one duck) had already ordered plastic tubs and other materials (underwritten by Standard Oil) and was working to organize the materials that were arriving. Rags were torn into usable size and paper was balled up to use as bedding. Boxes for holding the birds were being collected and organized at the far end of the long narrow area for holding the birds after they were cleaned. In the afternoon Greg visited Dr. Navieu in Pleasant Hill to find out more about cleaning and holding the types of birds most likely to arrive. On his return, he held a class for at least 150 people late in the afternoon. Around 4 pm the crisis actually became real for the volunteers.

And the birds came in a rush! They came all through the first night! They came in boxes and bags, and often cradled in peoples' arms. Some had been partially cleaned. In all, about 250 to 300 live birds arrived between 5 PM and midnight. Another 50 to 75 came during the night with at least 300 more reaching the Richmond facility during the 8 AM to 4 PM shift the next day. More than 40% of all the birds treated at Richmond arrived before Wednesday midnight.

It is difficult to convey the scene at Richmond during these thirty-six hours to any one who has not witnessed a volunteer cleaning a crude oil soaked bird with mineral oil, cornmeal, or flour and rags. In the words of one worker, "It was like the pictures of a Crimean War field hospital," or "a first aid station in the jungles of the South Pacific during World War II." Along tables with small tubs every two or three feet, each bird was attended by two or three people working from both sides of the table. When they ran out of table space people would cradle a tub in their lap while working with the bird from one side as someone else knelt and worked at the other.

The volunteers worked slowly and painstakingly, completely focused on the bird in front of them—there was very little chatter to break the concentration. They worked for hours knowing that as many as a hundred more birds were huddled in boxes waiting their turn. Men and women wept as they slowly and gently poured clean mineral oil over each feather, guiding it where possible to be most effective in sloughing off the dark, dirty crude oil, over and over and over again.

Few people were so affected emotionally by the oil spill as those who cleaned the birds. They had what seemed "endless time to think about the circumstances that had brought this horror about," in the words of one volunteer.

"There were moments when I couldn't face myself as a human being," said another, "that, I had contributed to this mess before me." Yet another said "Who could sleep tonight knowing that in each his own way we are just as guilty as Standard Oil?"

And undoubtedly no other group of people has responded for so long after this oil spill as the volunteers at Richmond. And today, March 2, 1971, exactly six weeks after the Richmond Center was opened, and six weeks and one day after the spill itself, these people are still responding on a volunteer basis many continuing to put in ten, twelve and fifteen hours days; still sleeping near the birds!

It is incredible that this has had to continue as a volunteer effort! Regardless of the personalities involved, regardless of any hip versus straight feelings, regardless of payment for services, it is the welfare of the birds that is now at stake!

These volunteers have established an unprecedented record in bird survival after an oil spill. Of the approximately 1,400 birds received alive more than 375 survived the first six weeks. Several have even been released on the judgment of the veterinary doctors who felt that they were in fit condition to survive in their natural habitat. Many of the others died within two or three hours of cleaning. The survival rate of the Richmond birds, and the smaller numbers similarly treated by Dr. Navieux, approaches 30% while the survival rates in other recent spills has only been around 3%. The latter figure compares favorably with the survival rate at the San Francisco Zoo, the other major bird holding center during the January 18 crude oil spill.

Why have the birds survived this long? Obviously a great deal of credit must go to Dr. Navieux's initial formula for treatment in cleaning. Some credit must go to the veterinarians and other medical/scientific specialists who, like Dr. Navieux, volunteered their knowledge, experience and efforts. The professionals from Standard Oil and various government agencies tended to lose the birds quickly, while the volunteer operations (Poor Richard's, Presidio, Richmond) tended to maintain life for much greater periods of time. And if the present trends hold, the volunteer operations will return perhaps the highest percentage of birds ever after a spill of this nature.

Of possible reasons for the survival two must stand out at this early writing. The first of these is humility, and the other is plain old tender loving care. Not knowing much of anything in the beginning, realizing it, the volunteers at Richmond learned a great deal more through observation than their more learned colleagues elsewhere. They were open to solutions, where a more orthodox mind couldn't observe the "pattern" before the life was gone from the bulk of the subjects. Many things have been learned that could have lowered the fatality rate even further. The grebes, for example, seem unable to live in pens of the size used at Richmond in quantities of more than five. The population of each pen has died down to four or five, and stabilized at that figure! The same thing seems to apply to the ducks, although in this case the pens seem able to contain nine or ten. Above those numbers, additional stresses increase mortality. Observers have also noted a definite pattern in the times of day when a bird is most likely to die.

In the matter of tender love care, some matters are obvious even to the most hard-nosed among us while others are much less so. It is easy to compare the cleaning of the birds at Richmond to a mother bathing her newborn child. This may be contrasted to the treatment observed at least one center in which birds were dunked head first into a degreasing solution, only the feet held out of the water. One attendant stated, It is certainly less stress to get it over with in a couple of minutes than to take the hours required when using mineral oil. Perhaps we should inform our hospital of the health benefit from dunking patients head first into barrels every time they need a bath. Or perhaps mothers should adopt this method in cleaning their children.

But that is only part of the story. People baby sat the birds during the early hours and for some days in most cases. In the Intensive Care Unit each person observed and treated only two or three birds in most instances during the early hours and even weeks later. The pens were constantly attended for weeks. And while there is some dispute as to the taming effect of this close human/bird relationship, there is also the fact that the birds are surviving at considerably higher rates than ever before. At question, of course, is whether this new relationship will interfere with a bird's return to the wild. Also, the care they have received in feeding may result in a later difficulty in foraging for themselves. These factors must be examined at some length. It is easy for a technician who has lost all his birds to grumble that the Richmond people are killing their birds with kindness. Perhaps so, but this has not yet been demonstrated. At the same time the birds are now eating live food, swimming and even starting to fly. As mentioned, some have been released, though survival is not guaranteed.

The radio and television stations are continuing to cover the story. Several national magazines have given extensive coverage, and many more such as National Geographic will be carrying articles in upcoming months. These birds will be in the news, one way or another, for a long time.

Ocean Beach oil spill cleanup, 1971.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

But undoubtedly the most important thing for these 400 birds is that the process will take them home, back to their place in nature. If the Richmond birds have done nothing else, they have demonstrated the cost of keeping such birds in captivity. We need to know much more about how to speed up the rehabilitation process and how to get the birds back to nature in the earliest possible time. As several people have said, in a slightly different place or at a slightly different time, we could have had 100,000 birds instead of the 5000 to 7000 that were recovered dead or alive.

What we have had here could well be a dress rehearsal for things to come.