Rising Tensions Engulf 1916 San Francisco: Class War Precedes World War I

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

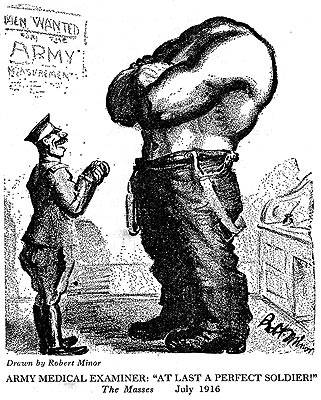

Cartoon by Robert Minor in The Masses 1916, a publication that would be shut down as a subversive organ during the early days of WWI the following year.

Image: author collection

San Francisco in 1916 was a long way from the mass slaughter and grinding trench warfare that held Europe in its grip. But that far-off conflict created enormous demand for California agricultural and manufactured products. In San Francisco prices were rising and business was booming. A severe recession in 1913-1914, which took place in a City still hurrying to rebuild and re-establish its prominence after 1906, had been ameliorated in part by the push to build a World’s Fairgrounds at Harbor View (today’s Marina District). San Francisco threw itself a huge party in 1915 as it opened itself to the world through the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE). The PPIE ran for most of 1915 during which a carefully negotiated labor peace also prevailed. But the corporatist deal between San Francisco businesses and its restive working class only held for the duration of the Fair itself (and even during the Fair there were some disputes, including a brief restaurant strike).

From the McNamara Brothers dynamiting of the Los Angeles Times in 1910 to bitter strikes that erupted in the industrialized fields of California agriculture, and other disputes that rocked PG&E, the Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Company, and other emerging corporations, the early 1910s had been a period of sharp class conflict. The PPIE truce of 1915 in San Francisco bottled up some of the tensions, while conflicts between the Building Trades Council, the Labor Council, and the remnants of the Union Labor Party (that had held the mayor’s office and most of the Board of Supervisors from 1901-1907, and then again briefly in 1911-1912) meant that workers were not a unified force by mid-decade. The end of the PPIE in November 1915 also brought to a close the agreement between local unions and business leaders regarding wages, working hours, strikes and production norms.

It wasn’t long into the new year of 1916 before workers began once again to flex their muscles. By the time 1916 was over, both California and the United States as a whole would see a doubling of strikes compared to the previous year.(1) As Spring began, workers aboard ships plying the Pacific Coast trade—sailors, marine firemen, and marine cooks and stewards—together demanded a $5 per month wage increase, and shipowners, enjoying booming business due to WWI, immediately granted the demand.(2)

But things were just getting started. The Laborers’ Union demanded a $3 daily minimum wage for workers who worked at all sorts of factories and construction sites around the City. In Bay Area shipyards, the rapidly expanding Boilermakers’ Union got higher pay for many journeymen and helpers. In May about 200 low-paid, unskilled, nonunion workers spontaneously walked out on strike at Bethlehem Steel’s Union Iron Works, and the Boilermakers stepped in to negotiate a wage increase for the wildcat strikers.

Bethlehem Star cover, c WW1.

Image: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco, CA

The half-century fight for an eight-hour day in San Francisco re-emerged as predictably as the fight for higher pay. In April, 1916, the Structural Iron Workers’ Union gave 90-days’ notice to Bay Area iron and steel shops that it would soon only work eight hours per day. Spring temperatures rose a bit higher on May 1 when the Miscellaneous Culinary Employees’ Union reduced the workday from 12 to 10 hours for its large membership of dishwashers and kitchen helpers. Later in the month the dishwashers and kitchen helpers joined cooks and waiters to demand immediate establishment of the eight-hour day for all culinary workers.

Meanwhile, the new automobile industry was partially paralyzed when auto mechanics struck against six of the largest auto companies in the City for $4.50 per day wages. Facing recalcitrant auto dealers, workers instituted a boycott, which became important in the months that followed because one of the union’s secret agents on the job was Warren Billings. Billings, a 22-year-old anarchist militant, had gotten out of jail a year earlier after serving 14 months for transporting dynamite from San Francisco to Sacramento during a PG&E strike. From inside the workplace he fed information to the Machinists’ Union leaders but also engaged in sabotage against cars still under maintenance guarantees that he found around Union Square.

Rolling into San Francisco’s typically foggy summer, 4,000 longshoremen struck Bay Area docks on June 1 for higher wages as part of the first-ever coast-wide strike to hit all major Pacific coast ports at the same time (ten thousand were on strike altogether). River and bay steamboatmen struck on the crucial transit link between Sacramento and the Bay Area, paralyzing riverboat traffic in pursuit of both a wage increase and a reduction in their long hours. Under the pressure of these cascading labor actions, and the free importation of strikebreakers pursued by shipowners, a brief truce was established on June 9 only to collapse by June 22 after several shootings and two longshoremen killed.

Fallen power towers for the Sierra and San Francisco power company, supplier to United Railroads, blown up during the night of June 10-11, 1916.

Photo: SFMTA Photo U05361

On June 10, Tom Mooney and his wife Rena held a meeting at the Woodmans’ Hall for United Railroads (URR) streetcar workers, a.k.a. carmen, to reorganize their once powerful union (it had been broken during a bitter and violent strike in 1907). At about 10 p.m. that night Mooney called for a break in the meeting and several undercover cops in the crowd ran out and drove away, thinking that Mooney had ended the meeting. Instead he resumed it a few minutes later and stayed for another hour, deciding late to suspend plans for a wildcat strike the next day due to insufficient support.(3) Late that night three small bombs exploded on San Bruno Mountain south of San Francisco, destroying a power tower bringing power in to the United Railroads System (conveniently the power had been diverted around the downed towers before their destruction). Witnesses who claimed they saw someone who looked like Tom Mooney at the scene were never called to testify (though their affidavits were given to investigators after the July 22 Preparedness Bombing) since there was not a strike on the streetcars the next day as the owners had expected, and the plan to use the explosions to discredit the strike was unnecessary.

In this tense midsummer climate the newly expanded San Francisco Chamber of Commerce publicly proclaimed their support for the open shop (though the Waterfront Employers Union formally disavowed any intention of pursuing an open-shop campaign against the longshoremen with whom they were locked in dispute). Feeling an opportunity to consolidate and expand their new organizational strength, Chamber president Frederick Koster convened a meeting on July 10 of hundreds of businessmen, including leaders of Bank of California, Southern Pacific Railroad, Capt. Robert Dollar, the largest canning company, and others to found the “Law and Order Committee,” which within a week had a half million dollars pledged from various San Francisco businesses. Two of its five members were known for the unyielding resistance to unionization: George M. Rolph of the C&H Sugar Company and C.R. Johnson of the Union Lumber Company.

Union leaders faced the prospect of a well-financed, well-organized consortium of local and transnational businesses headquartered in San Francisco leading an effort to break the reputation of the City as a union town. Longshore leaders, already in a difficult fight on the waterfront without much popular support, saw their membership vote to end the strike on July 17. When they abandoned their striking brothers in San Pedro in the South and the Pacific Northwest, whose strikes eventually failed, the Bay Area union ultimately seceded, dividing the briefly enjoyed coast-wide unity.

The push by culinary unions for the 8-hour day was met with a lockout by organized restaurateurs with full support of Chamber of Commerce and Law and Order Committee. Ironically this might have lost the 1916 Presidential election for the Republican candidate Charles Hughes. During the campaign Hughes arrived in San Francisco in the midst of the restaurant lockout. Some say he lost the November election to Woodrow Wilson when he dined at the open-shop Commercial Club because he went on to lose union-friendly San Francisco by 15,000 votes, and California by a narrow 4,000 votes… which gave the presidency to Woodrow Wilson a second time. For local restaurateurs the lockout was a success. On December 15, 1916 the Labor Council called off the restaurant strike admitting defeat. Cooks and waiters membership fell from 3000 to 1200.

But the most dramatic event of the hot summer of 1916 was definitely the Preparedness Day bombing. Preparedness Day was a big demonstration called by the Chamber of Commerce and its business allies to drum up support for entering WWI on the side of the Allies (British, French, and Russians) and against the Germans. At 2:04 pm during the march, at the corner of Spear and Market (where the Federal Reserve stands today, and where the Occupy San Francisco movement began in 2011), a terrorist bomb detonated, killing ten and injuring more than 40. Within an hour of the bombing the police had destroyed the scene of the crime and evidence had disappeared as people freely took souvenirs from the area. District Attorney Charles Fickert, who had made his name after his original election in 1909 by dropping the remaining graft charges against San Francisco’s leading industrialists, appointed a special investigator for the bombing: Martin Swanson, head of the private detective agency called the Public Utilities Protective Bureau (chief clients, PG&E and URR). Swanson, who had been tailing Mooney and his associates all spring to help thwart their efforts to organize URR carmen, organized the raids and arrests of local radicals associated with Tom Mooney, including Warren Billings, Rena Mooney, Ed Nolan, and Irving Weinberg. The ultimate story is far too complicated to relate here, but Billings was convicted first and sentenced to life in prison, then Mooney who got a death sentence, but by the time they got around to the trials for the remaining defendants, the fake evidence and witnesses had fallen apart.

Years later the Wickersham Commission described the witnesses as “a weird procession consisting of a prostitute, two syphilitics, a psychopathic liar, and a woman suffering from a spiritualistic-hallucination.”(4) Crucial evidence exonerating the defendants was suppressed for more than a decade, and though Mooney’s sentence was commuted to life in prison after worldwide pressure induced President Wilson to intercede with the California governor, Mooney wasn’t pardoned until 1939 and Billings not until 1943! The actual bombers were never discovered. Theories include German saboteurs angry about the support for their enemies, Mexican revolutionaries angry that the U.S. army was about to enter Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa, or even other anarchists who were anti-WWI (Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman were living on Dolores Park during this period and publishing their journal called The Blast!).

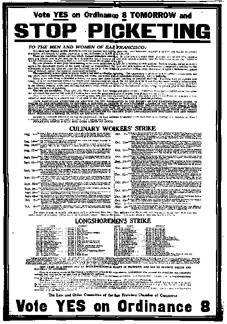

Citywide hysteria and anti-radical sentiment inflamed by the lurid coverage of the capture and prosecution of the alleged attackers bolstered the Chamber of Commerce’s anti-labor campaign. A well-financed effort in the fall election led to the passage of a blanket anti-picketing ordinance 74,000 to 69,000. Lumber workers fought a 3-month strike from August to November and lost to the owners who insisted on an open shop.

The Chamber of Commerce successfully sponsored a municipal ordinance in 1916 banning picketing.

On the other hand, the 8-hour day campaign of the Structural Iron Workers fractured the iron foundries and by early 1917, the iron workers had prevailed and the Law and Order Committee and the open shop agitation had failed. The iron workers were helped by Mayor Sunny Jim Rolph’s denunciation of the Law and Order Committee for dissembling an intention to destroyed organized labor, and his firing of one of the main strike-breaking firms then employed in construction at General Hospital.

The United States formally entered WWI in April 1917. Radical newspapers were censored, the Industrial Workers of the World were suppressed, and the surging radicalism of the early 20th century was halted. The Russian Revolution and working class uprisings in Germany helped bring an end to the war by November 1918, and soon after the war west coast strikes were met with violence and by 1919-1920 over 10,000 radicals were rounded up and deported by A. Mitchell Palmer, attorney general of the United States (with help from his assistant, J.Edgar Hoover, later to head the FBI for almost six decades). San Francisco entered the 1920s apparently enthused about the “American Plan” which promised prosperity through open shops, stock market profits, consumerism, automobiles, and radio…

Notes

1. Industrial Relations in the San Francisco Bay Area 1900-1918, by Robert E.L. Knight, 1960: UC Press, p. 299

2. Ibid, p 301

3. Frame-up: The Incredible Case of Tom Mooney and Warren Billings by Curt Gentry, W.W. Norton & Co. (New York: 1967), p, 69

4. Ibid. p. 99

__________________________________________________________________

Fallen power towers for the Sierra and San Francisco power company, supplier to United Railroads, blown up during the night of June 10-11, 1916.

Photo: SFMTA Photo U05359

On the morning of June 10, 1916 these notices were posted inside United Railroad carbarns in San Francisco:

June 10th, 1916— NOTICE TO EMPLOYEES

This is to inform you that one Thomas J. Mooney, a moulder by trade, but at present unemployed, who was arrested and confined in jail as a dynamiter for his activities during the Pacific Gas and Electric Company's strike in 1913, is at present endeavoring to enroll some of our employees in the Carmen's Union. It is needless to advise you that the company is thoroughly familiar with his every move and takes this occasion to notify you that any man found to be affiliated with Mooney or any union, will be promptly discharged.

—United Railroads of San Francisco

That night, June 10th, Tom Mooney rode to a union meeting at Woodman's Hall on 17th Street. In spite of more than 30 armed men surrounding the entrance, Mooney and a couple of hundred men came in to the meeting (the number of actual carmen may have been small, as there were many spies present as well). Although a wildcat strike was discussed at length, Mooney was so discouraged by the poor turnout that he didn't even bring a strike to a vote. At about 10 p.m., Mooney called a brief recess and went to a small nearby room. One of the URR spies, thinking Mooney had left the building, was observed going to tell some of the railroad's goons that Mooney was gone. The meeting resumed shortly and didn't finish until about 1 a.m.

It was fairly obvious to Mooney and his friends that an attempt was being made to kill the strike before it started by railroading its organizer on a phony dynamiting charge... If it was a frame-up (only a supposition), two errors were probably responsible for it going awry. One was that Martin Swanson [chief of security for PG&E, employed by URR, PacTel, and others to counter organized labor] who was at the scene minutes after the explosion, where he found a suitcase of unexploded dynamite and a clock-timing device - thought Mooney had left the meeting shortly after ten. Several witnesses saw a man dressed like Mooney carrying two suitcases near the towers about 11 p.m. (Swanson had their affidavits, which he would turn over to Fickert after the Preparedness Day bombing). At 11, however, Mooney was presiding over the organizational meeting, as some 200 men could verify, having been out of the room only a few minutes, far less time than would have been required for him to go to San Bruno, much less there and back.

--excerpted from Curt Gentry, Frame-Up (New York: W.W. Norton 1967)