People's Food System

Historical Essay

by Jesse Drew

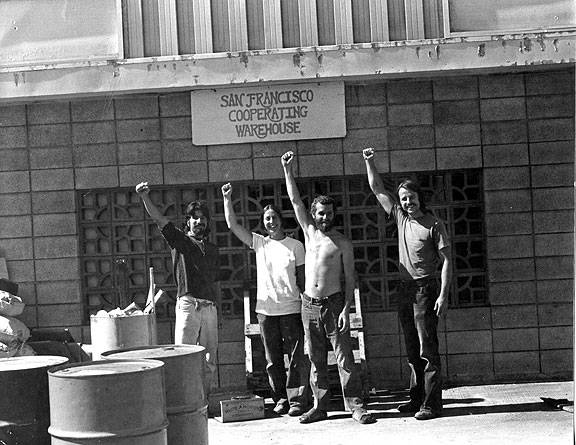

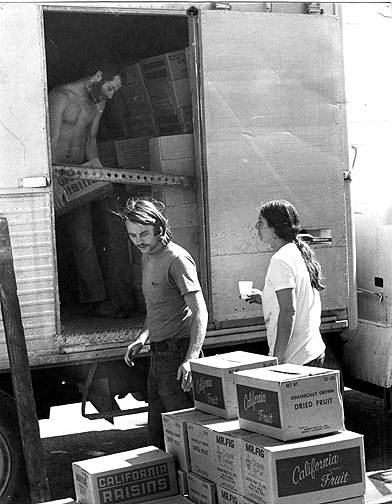

Workers at the Cooperating Warehouse loading dock, c. 1976.

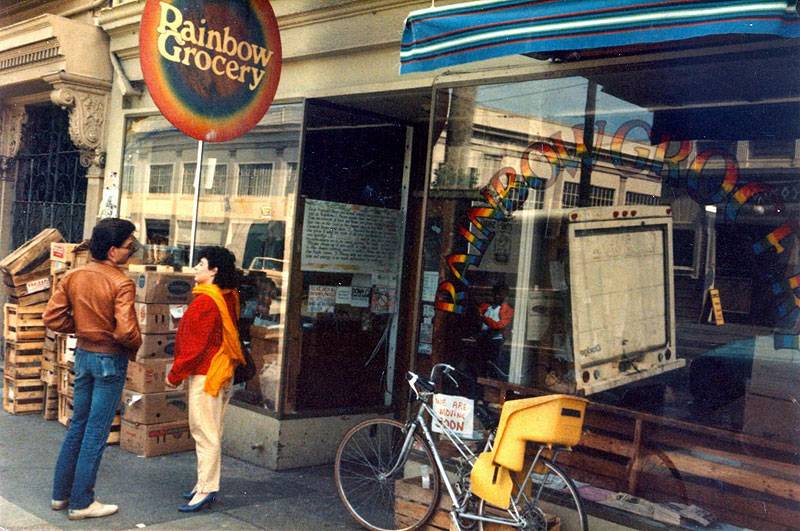

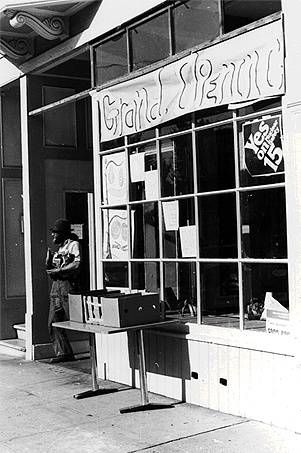

Rainbow Grocery on 16th Street in the 1970s.

Photo: courtesy Judy Davis

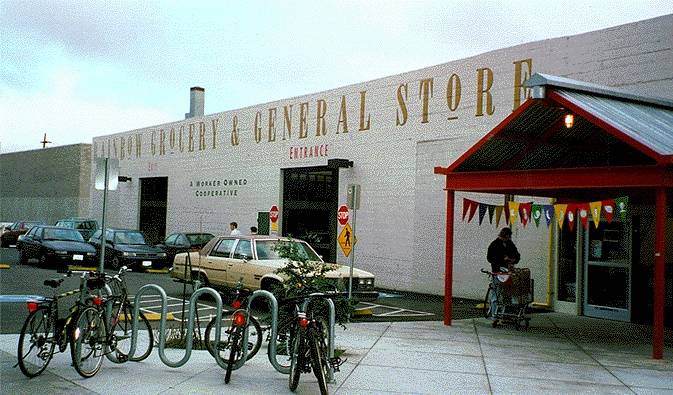

The old Rainbow Grocery at 15th and Mission in 1995.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The new Rainbow Grocery on Division Street, 1997

Photo: Chris Carlsson

After twenty years, Rainbow's store on Division is more lived in...

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2021

| In the 1970s, collaborative “food conspiracies” began to recede and food activists founded a network of worker-owned cooperative stores and businesses that became known as the People’s Food System. Offering employment to recently paroled prisoners and refugees from Central America, the system put its values into practice internally and externally. Campaigns to improve nutrition and to understand better the politics of international food industries, as well as the politics of various food choices, helped seed consumer demand for healthier and more organic alternatives, later widely adopted by mainstream grocery stores and restaurants. |

Many of the core members of the local food-buying clubs began to discuss the feasibility of abandoning the food conspiracy model, and opening up storefronts instead. These co-op stores first appeared in the mid 1970s, and soon sprouted all over town. These included Seeds of Life (Semillas de Vida) on 24th Street in the Mission, Rainbow Grocery on 16th Street in the Mission, the Haight store in the Haight-Ashbury, and Good Life Grocery on Potrero Hill. By and large, the stores were run by worker-owned collectives, with workers who rotated jobs within the stores and used some form of profit-sharing for payment. The stores featured boxes of organic vegetables, wooden bins of bulk beans, grains and dry goods, large plastic buckets of honeys, oils, and nut butters, and perhaps a section for whole wheat breads and other baked goods.

The stores provided visibility for the political and social concerns of the collective members and allowed them to earn a living from productive, non-exploitative work. Jobs were offered to people in dire need of employment, such as recently paroled prisoners and refugees from Central America. Although some people were critical of the abandonment of the food conspiracy principle that all must perform work to reap the benefits of cooperative buying, the food stores were successful in spreading the benefits of cheap and healthy eating to poor and working people, who were formerly excluded from such counter-cultural experiences.

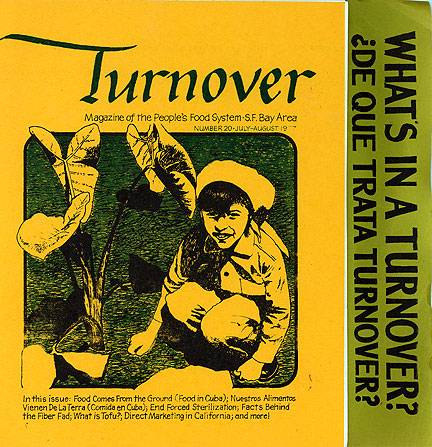

The bulk of these food stores came together to form the People's Food System. A formal network of stores provided economic and logistical advantages as well as greater political influence for activists trying to make the link between radical social change and what people eat. Turnover, the magazine of the People's Food System, illustrated the symbiosis of politics and food in its numerous issues. Issue 20, for example, had articles on food production in Cuba (in English and Spanish), facts "behind the fiber fad," information on the Nestles boycott, and an article entitled "What is tofu?"

Turnover Issue 20, July-Aug. 1977

With a network of stores, other peripheral collectives came into being as well, to support the growing distribution system. People's Bakery and Uprisings Bakery baked the bread, Merry Milk and Red Star Cheese provided the dairy, Veritable Vegetable provided the vegetables, and People's Warehouse handled the central warehousing aspects. The People's Food System, by the late 1970s, was employing hundreds of people, and feeding thousands cheap, nutritious food, while promoting the benefits of collective work, not-for-profit economics, and radical social change.

Instead of $70.00 worth of top quality food, the people have gotten $8.00 worth of mediocre food. Instead of fresh meat, half the people received one chicken. Many stood in long, cold lines for only a bag full of cabbages, while others stood in line and got nothing at all.

- —The Symbionese Liberation Army criticizing the Hearst's half-hearted efforts to comply with the SLA demand to distribute a million dollars worth of food, in exchange for their kidnapped daughter, Patty Hearst.

It sounds like most of the food is of low quality. No one received any beef or lamb, and it certainly didn't sound like the kind of food our family is used to eating.

- —Patty Hearst agreeing with her SLA captors complaints

It's just too bad we can't have an epidemic of botulism. . . There is a characteristic on the part of the people that they want something for nothing.

- —Ronald Reagan, commenting on the 30,000 people who showed up to collect free food from the SLA ransom demands.

Thanks to several, sometimes horrible ironies, the politics of food remained a central focus for the Bay Area during the mid-seventies. The Symbionese Liberation Army kidnapped Hearst heiress Patty Hearst and demanded that the Hearst's deliver $1 million of food to poor people, including San Francisco's Fillmore district. Another underground guerrilla group, the New World Liberation Front, began a campaign of bombings against Safeway supermarkets, demanding better food at cheaper cost. Doggie Diner, the once ubiquitous hot dog stand (with the large sculpture of a dachshund that appears to be choking to death) was bombed at least once. McDonald's, when it first attempted to raise their golden arches on Haight Street, was picketed for many months, before being firebombed. In the jungles of Guyana, Jim Jones of People's Temple, murdered hundreds of his followers with a deadly batch of Kool-Aid. And in the murder trial of Dan White, the assassin of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk, the jury agreed that Dan had eaten too many Twinkies and drunk too much Coke, and was therefore not entirely responsible for his murderous actions. The largest riot in San Francisco history followed his slap-on-the-wrist.

Shoot Out at the People's Warehouse

The People's Food System was not just a network of food stores. Its members saw it as an organization dedicated to radical social change, mostly agreeing on the importance of democratic procedure in running a collective organization. The People's Food System also attracted people who were interested in using the System for their own ends. One such group was Tribal Thumb, a small collective of people who were connected to an eatery called Wellsprings Reunion, located in the South of Market area. The leader of the group, Earl Satcher, was a saxophone-playing ex-convict whom many people saw as the "cult" leader of the Wellsprings group. Tribal Thumb and a few allies in Veritable Vegetables were accused of intimidating members and trying to take over the People's Food System. The dispute escalated into threats of violence and led to several secretly held meetings of the People's Food System to discuss what actions should be taken. An emergency meeting was held on April 26, 1977 at the People's Warehouse space. Called to discuss the expulsion of members deemed disruptive to the organization, the meeting degenerated into a hostile confrontation between opposing sides. Tribal Thumb members and their allies (including two Dobermans), were in the parking lot, reportedly intimidating and threatening Food System representatives against voting for the expulsion of disruptive members. During the break, gunfire broke out in the parking lot, leaving ex-San Quentin 6 member Willie Tate critically wounded. Tribal Thumb leader Earl Satcher was shot dead. Although the shock of the gunfight soon wore off, the Food System began to succumb to larger changes.

Into the Mainstream

By the end of the 1970s, a distinct change could be discerned in the supermarkets and groceries of the Bay Area. Items formerly found only in co-ops or health food stores were appearing on the shelves. Large numbers of people sought out healthy alternatives to the "plastic" American food fare, as whole foods entered the mainstream. Cheez Whiz and Tang made way for rennet-less, low-fat cheddar and organic apple cider. Reaganism and a resurgent right-wing prompted many of the workers in the Food System to put their political energies elsewhere, such as in the growing anti-nuclear movement or in Central America solidarity work. Long hours for low pay also began to take its toll on Food System members. Most stores quietly disappeared, although a few hung on for quite a while. Today, the glowing exception to the demise of the People's Food System is the newly expanded Rainbow Grocery on Folsom Street.

—Jesse Drew, excerpted from "Call Any Vegetable: The Politics of Food in the San Francisco Bay Area" in Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics and Culture (San Francisco: City Lights Books 1998)

Inner Sunset Community Foodstore opens in 1975 on 9th Avenue.

Photo: Teitelbaum

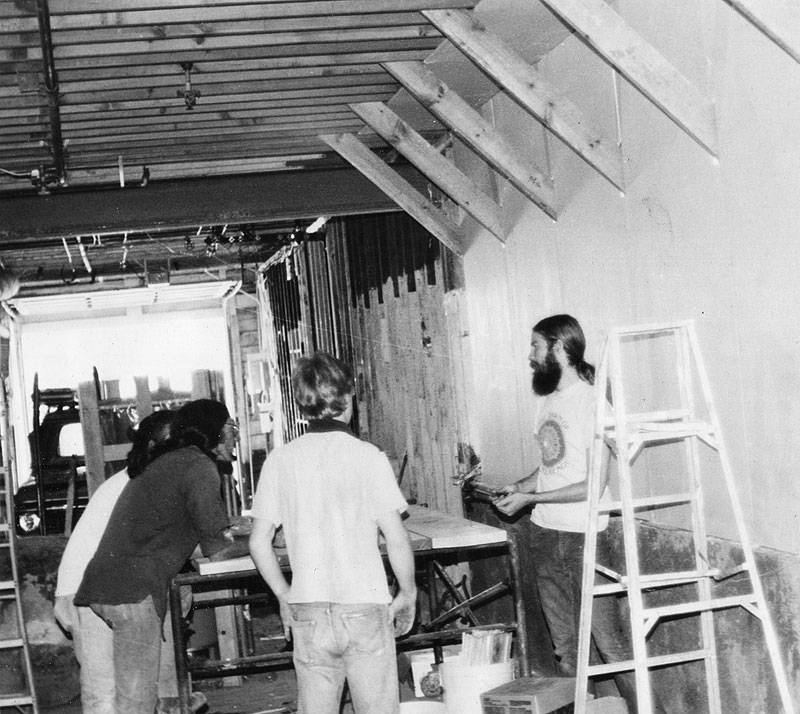

The collective at the Inner Sunset Community Food Store working on their new store over on Irving Street after they were forced to move back in 1982.

Photo and caption: Roger Herriod

That's an interesting story where the greedy property owner thought they could duplicate what the collective was doing and put up a mirror version of what we did after they forced us out. It of course failed as our customers all moved to the new place a couple blocks away. I was opposed to the plan to move to Irving and wanted to move into the Haight but Phil Bewely and the other guy who both eventually moved over to Rainbow grocery were dead set on a conservative agenda along the lines of packaging which got me booted out of the collective for my bulk agenda. This image is of me with Charlie Englestein (3rd from right with the glasses) who is bending over talking about the next steps in converting the former plumbing shop... Charlie was of course the main guy coordinating the project. I was the sheet rock guy as I was also doing produce shifts at the store... I'm the tall skinny guy on the right with the beard and long hair.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/judydavisfinal" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Long-time Rainbow worker Judy Davis recounts her history as a member of the workers' cooperative since it was on 16th Street.

Video: Shaping San Francisco