Oakland Rising: The Industrialization of Alameda County

Historical Essay

by Richard Walker, 2005

Originally written for The Manufactured Metropolis, edited by Robert Lewis, Temple University Press. This is part two focused on Oakland and the East Bay. Part one on San Francisco is here.

Figure 4: Aerial map of Bay Area, c. 1936

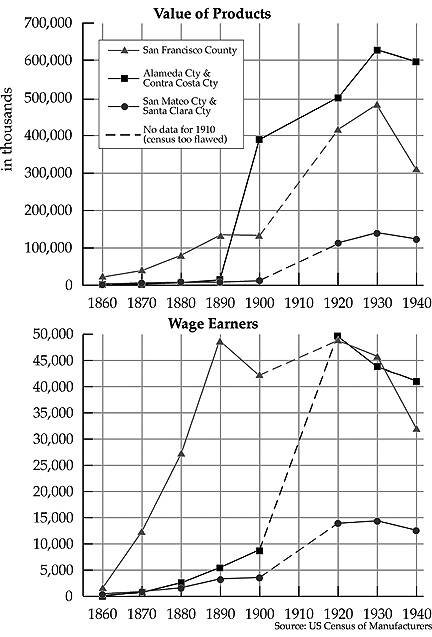

The foreward wave of regional growth had shifted by 1900 to Oakland and the greater East Bay. Alameda and Contra Costa counties together surpassed San Francisco and the West Bay (including San Mateo county) in manufacturing employees and value of output by 1910. The rapid acceleration of East Bay urbanization that went along with this industrial surge would create the greater Bay Area metropolis of the 20th century (Figures 1 and 4).

Figure 1: Manufacturing employment and output by county groups, 1860-1940

Oakland began as one of several small towns around the Bay, with the usual smattering of resource industries. By 1869, it could count sixteen factories, including sawmills, tanneries, slaughterhouses, dairies, a jute mill, flour mill, drydocks and a brewery (the only thing out of the ordinary was a boot and shoe maker). The big turning point was the arrival of the Central Pacific in 1869, after which population climbed from 10,500 to 35,000 in a decade — making Oakland the second city in the western United States for a generation. Although the rail terminus was officially San Francisco (trains were ferried across the bay from the 7th Street mole), the railyards were a major employer in West Oakland and an attraction for manufacturers seeking access to California markets. Oakland industrialized rapidly through the rest of the century. Factories became abundant in the 1870s and the 1880s saw another thirty establishments spring up. By 1890 California Cotton was the largest cloth mill in the West, Josiah Lusk the biggest cannery, Pacific Coast Borax the largest producer of cleanser, and Lowell Manufacturing the biggest carriage works. But the best was yet to come, and Oakland still looked more like a satellite of San Franisco's diversified manufacturing complex than a realm of its own.(34)

The principal axes of Oakland's industrial belt ran along the waterfront and were reinforced by the rail line coming from the east along the estuary all the way to Oakland Point (1869), where it met a second line arriving from the north (1873). The principal manufacturing node lay within the original Oakland city grid, which ran from the waterfront to 12th Street with Broadway as the central thoroughfare. Machining and woodworking were a fixture of the central district. A second cluster appeared a mile and half west, in an area platted and annexed in the 1860s. The defining activity of West Oakland was the railyards, but beyond them at Oakland Point (long gone due to surrounding fill) lay such space-extensive functions as lumber yards, shipyards, stockyards, tanneries, and slaughterhouses. A third cluster could be found two to three miles east across Lake Merritt in the Brooklyn and Fruit Vale districts (settled in the 1850s and annexed in 1872), which featured the Cal Cotton mill, the boot and shoe factory, saw and planing mills, early canneries, a flour mill, a pottery factory, and tanneries. A fourth formed in the 1880s and 90s two and half miles north of downtown along Temescal Creek, beyond the city limits, in what would later become Emeryville (incorporated 1899) and North Oakland (annexed 1897). Some of the largest factories in town such as Judson Steel and Lowell Manufacturing moved to the Emery district, while up the creek the principle site was the J. Lusk cannery with 400 acres of fruit and vegetable gardens in the Temescal district. (Pacific Coast Borax and N. Clark & Sons Brick Works were across the estuary in Alameda Point and there was another small industrial settlement at Oceanview, now West Berkeley, to the far north).

The initial locus of housing was the 1850 city grid, with small settlements around workplaces in Brooklyn (Clinton and San Antonio districts) and Fruit Vale to the east. A few wealthy burghers like James DeFremery and George Pardee moved into the wide open spaces to the west, but after 1869 that area blossomed as a working class district and the rich were displaced to the northeast around and across Lake Merritt. West Oakland filled in rapidly all the way up to 50th Street (roughly Temescal Creek) which gave the city a lopsided appearance for decades. Workers commuted by foot from the flatlands east of the industrial belt or rode the streetcars fanning out from downtown and West Oakland in a manner still clearly visible in the diagonals overlaying the regular street grids. The little industrial communities of Brooklyn — which grew less rapidly — retained their distinct identities long after incorporation, each with its own street grid, retail commerce and ethnic flavor. For example, Jingletown, where Jack London grew up, still looks like any eastern mill village with an ethnic, Catholic working class, though it has gone from Irish to Portuguese to Mexican and was bisected by a freeway in the 1940s.

Portuguese workers at California Cotton Mill in Oakland, 1895.

Photo: Peralta House

The Jingletown Cotton Mill abuts the Nimitz Freeway (I-880) and has been converted to "artists lofts," 2015.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The bay made Oakland a twin city rather than a suburb, but it was not a strong antipode to San Francisco in the 19th century. While many manufacturing companies were locally owned, giving the city a potentially independent economic base, the town’s leading burghers, Horace Carpentier and Samuel Merritt, were master land speculators rather than industrialists. The local bourgeoisie gave away the waterfront not once but twice to private owners (themselves!), who turned it over to the Central Pacific based in San Francisco (indeed, Carpentier, Oakland's first mayor, worked as a lawyer for the railroad before he took the money and ran to New York). It took the city fifty years to regain control of its harbor (1911). Stirrings of boosterism could be found, such as the bold proposal for a cross-bay bridge as early as 1863, but San Francisco capitalists felt little threat and were happy to join in Oakland’s growth by investing in such things as a cable car system, paint factory, and real estate promotions.(35)

The sea-change came after the depression of 1893-95. Oakland and the East Bay began a meteoric ascent, becoming an early metropolitan ‘edge city’. Oakland was one of three fastest growing cities in the US from 1900 to 1930, jumping from 67,000 to 284,000, and development spilled over into neighboring towns of San Leandro (1872), Berkeley (1878), Alameda (1884) and Emeryville (1899). The earthquake of 1906 doubled Alameda county’s population and industry overnight, and there was another a trebling of employment during the boom of the First World War. Output continued to rise in the 1920s, although employment slipped. (Figure 1) Oakland was no longer an outlier of the metropolitan core, but a distinctive industrial arena in full bloom (Figure 5). Breakthroughs in transportation were important, of course: repossession of the waterfront from the Southern Pacific allowed the city to develop its own port facilities and the arrival of the Santa Fe (circa 1900) and Western Pacific (circa 1910) lowered freight rates. The East Bay grew on water and rails, not trucks, well into the 20th century. But the port and rail system grew to serve industry, as much as, if not more than, the other way around.(36)

Figure 5: Map of East Bay industrial belt, 1926

Fundamental to the industrialization of the East Bay were the emergence of new leading sectors and major reorientations in older ones. First among Alameda county’s peacetime industries after 1900 was food processing, chiefly canning. The East Bay became the principal node in the Bay Area's largest industry, which led the nation in canning output from 1890 to 1940. California packers and canners introduced the first name-brands in food, standardization of produce, and mass advertising in foodstuffs (Del Monte brand was dreamed up at the Lusk company). They later set up the world’s most advanced marketing and contracting system, tied to the new supermarket chains (such as Oakland’s Safeway). And they innovated new methods and products, such as the canned olive (invented in Oakland). A major organizational restructuring of canning took place as well, as the industry underwent a marked concentration. In 1899 a dozen companies merged into the California Fruit Canners Association, headquartered in Oakland; in 1917 this group expanded into the giant CalPak (Del Monte) corporation, the leading agribusiness firm for much of the 20th century (though its headquarters moved to San Francisco). A host of suppliers provided cans, jars, crates and cartons to store and ship produce, as well as a stream of innovative machinery, such as pitters, peelers, and steamers. Many other food products were manufactured in the East Bay, including cereal, meat, and bread. Closely related were a dozen soap and cosmetics manufacturers. These factories were distributed along the length of the East Bay industrial belt and well into the outlying farming areas of southern Alameda county.(37)

Oakland’s second leading sector was metal working and machinery, which continued a long tradition in the Bay Area — but in a new era of steel alloys and high-speed cutting. Machine shops and foundries proliferated, clustering around downtown and along the estuary-rail corridor. Oakland companies such as Union Machine Works, Bay City iron and Vulcan Foundry made machines for packaging, road grading, clothes washing, canning, and chemicals, as well as boilers, engines, turbines and cast parts, some of which were unprecedented products. Upstream from metalworking was steel production, which finally developed as a significant industry in California in the 20th century. The East Bay steel district, focused on Emeryville, was one of three that grew up around the Bay Area at the same time (the others were South San Francisco and Pittsburg, in Contra Costa county).(38)

The metal trades extended in several new directions. For a brief time, the Oakland estuary developed into an exceptional shipbuilding district. This was based on companies transferring operations from San Francisco and on wartime orders. Wooden shipbuilding migrated first to the estuary in the 1890s, later joined by Moore and Scott (later Moore Drydock) and Bethlehem (moving most of Union Iron Works’ former operations). During the peak years of the World War there were a dozen shipbuilders employing 40,000 men, putting out 18% of US production. Several companies supplied marine engines. The shift from San Francisco to Oakland appears to be tied to technical and product changes, such as steel construction, the Dreadnaught class of battleships, and oil tankers.(39)

No sector better exemplified the new age than automobiles and Fordist mass production, which swept into Oakland from Detroit in the ‘teens. The city became host to over fifty assembly and component plants in the interwar period. Chevrolet was first, in 1916 , followed by Durant, Star and Willys-Overland. Another pioneer was Coast Tire and Rubber in 1919, which was rapidly joined by a variety of tire and parts makers. Many of these were local companies, as were specialty assemblers like Fageol (buses) and Benjamin Holt (tractors). Holt's caterpillar tractors, invented in Stockton for the Sacramento Delta, would revolutionize farming, warfare and earth-moving around the world within a generation. The auto age filled in the vast expanse of East Oakland, after Chevy jumped 7.5 miles out to empty fields at Foothill and 70th Avenue (Figure 6).(40)

Figure 6: Aerial photo of Eastmont Chevy plant, c. 1918

The brand-new electrical machinery industry entered Oakland and the East Bay in the 1910s with an influx of branch plants from General Electric, Westinghouse, Western Electric, and Victor, as well as local operations such as Marchand and Magnavox. These factories manufactured lamps, motors, calculators, phonographs, and loudspeakers (invented in Napa). Aircraft were a promising East Bay industry in the biplane era; some thirty-five East Bay factories supplied airplane parts in World War I, including a United Airlines plant and Standard Gas Engine in Oakland and Jacuzzi and Hall-Scott Motors in Berkeley. For a time the new Oakland airport, completed in 1926 at the eastern edge of the city, was the premier airfield on the Pacific Coast.

The new wave of industrialization stretched the metropolitan area of Alameda county dramatically north and east. Hand in hand with industry growth came extensive residential development and land speculation. As westside industry built up, the flatlands of the north county up through Berkeley and Albany (1908) filled in, creating a sea of small homes of the working class. During its period of rapid growth from 1900 to 1930, the East Bay developed one of the most extensive streetcar systems in the country, led by the Key System. Trolleys and good wages allowed for considerable lateral mobility; so workers moved eastward all the way to the edge of the upper class redoubts in the foothills. East Oakland beyond Fruitvale — largely vacant until the First World War despite annexation in 1908 — filled in rapidly during the 1920s. Subsequently, tracts such as Melrose Highlands, built by the Realty Syndicate, and Havenscourt, built by Wickham Havens, were developed expressly for workers at the new auto factories.(41)

Key System map, early 20th century

Key train passing in front of the Grand Lake theater, 1930s.

Photo: Oakland History, Facebook

The East Bay has its own striking examples of local political initiatives to steer development. One was the creation of Emeryville. At a stroke, an emerging satellite of Oakland became an independent city devoted wholly to industry — one of the first such entities in the United States, twelve years before the incorporation of South San Francisco. By 1935 little Emeryville (only 1.2 square miles) was home to over one hundred manufacturing plants. The town excluded all but a few hundred working class residents and operated as a tax haven and friendly government to industry. The manager of Judson steel, Walter Christie, served as Mayor for the first forty years of the town’s existence, and was succeded by Al LaCoste, a packinghouse boss, who ruled for the next three decades. But even reputable Berkeley put in a sophisticated zoning ordinance c 1910 to protect factory owners from complaints by residential neighbors.(42)

By the turn of the century, Oakland was generating powerful capitalists of its own willing to do battle with San Francisco over water supplies, port expansion, and industrial growth. A Greater Oakland movement got underway in 1896 to push for civic improvements and the Chamber of Commerce campaigned tirelessly to attract investors. Francis Marion Smith was Oakland’s first great booster capitalist, who put together the Key System of trolleys and built his Realty Syndicate into one of the biggest residential developers in the country (13,000 acres in 1900, almost 100 tracts complete by 1911). George Pardee, Mayor 1893-1895, went on to be Governor of California, while Joseph Knowland became a powerful voice for local interests while serving six terms in Congress. The iconic figure of the New Oakland was non-partisan Mayor Mott (1905-1915), who brought several civic improvement plans to fruition. One was a skyscraper City Hall that turned its backside to San Francisco. Another was the liberation of the port from Southern Pacific. Mott aggressively annexed all of East Oakland while it was still open land, and tried to forcibly add Berkeley. Labor repression was something Oakland’s burghers distinguished themselves by, as when Mayor Pardee and Councilman Mott handed out pickhandles to vigilantes confronting Coxie’s Army of the poor in 1893.

By the 1920s Oakland was a major player in California politics. Joseph Knowland, who bought the city’s main newspaper The Tribune, became Oakland’s chief power-broker and the leading force in the state Republican party for thirty years. He promoted Earl Warren to District Attorney and then Governor of California 1940-1954, and his son, William to US Senator and Senate Minority Leader in the 1940s and 1950s. Henry Kaiser and Walter Bechtel built their construction empires out of Oakland in the 1920s and 30s, partly on the strength of local projects such as the Alameda Tube, the Bay Bridge and the Caldecott Tunnel. Kaiser led the Six Companies in building Boulder Dam, then became a figure of national importance in the Democratic Party by allying with Franklin Roosevelt (during World War II he would be one of the world's largest employers, with roughly 250,000 workers in his shipyards, building sites and factories).(43)

San Francisco’s business leaders were alert to the challenge presented by Oakland to their hegemony over a burgeoning metropolis. Hoping to follow the lead of New York’s metropolitan consolidation and LA’s aggressive annexations, James Phelan and his Progressive allies put together a Greater San Francisco Association to try for political unification of the region. This plan went down to defeat in a statewide vote in 1912, against opposition led by Joe Knowland and Oakland's business community. Attempts to formalize a cooperative relation under a Regional Plan Association started by Phelan in the 1920s also came to naught. Oakland's own attempts to annex Berkeley in 1908 or to merge city and county in the late 1920s failed just as miserably. Of course, the regional business class on both sides of the bay was acutely aware of the challenge presented by Los Angeles to the economic supremacy of the north, so some cooperation was possible. In the 1910s Oakland’s leaders supported the Hetch Hetchy water plan, the Panama-Pacific Exhibition, and regional unification by bridge, interurban rail and state highways. And during the Depression era regional leaders were able to pull together on such infrastructural projects as the trans-bay bridges.(44)

All the same, San Francisco capitalists, undaunted by shifting industrial geography or political opposition, kept investing in an expansive metropolitan fringe around the Bay Area. In Oakland, they were backers or owners of such firms as Parr Terminal, Moore-Scott ships, and Hunt Brothers canners. They invested in the East Bay’s streetcar, rail, gas and electric infrastructure. Industrial rivalries made little difference to financiers and realtors, who could play both sides of the table and hedge their bets. Oakland Bank of Savings merged with San Francisco's Mercantile Trust to form American Bank and Trust Company, the region's second largest bank, in 1921. Bank of Italy opened branches there, and Coldwell, Cornwall and Banker joined the rush in the 1920s. Several leading San Francisco businessmen, such as Wallace Alexander and Isaias Hellman, made their homes in Oakland’s posh hills by the 1910s.

The Contra Costa Shore

The northern tier of the new East Bay industrial belt appeared from the 1870s to the 1920s in Contra Costa county along the banks of the Sacramento River. Contra Costa specialized in giant resource-intensive plants, processing explosives, chemicals, oil, sugar, cement, lumber, silver, lead and steel. It leapt into the picture quite suddenly in the 1890s, and by 1900 the country's industrial output exceeded that of Alameda county (Figure 1). By 1906 some forty factories had opened along the river’s south shore, including more than a half-dozen of the largest factories of their kind in the country in the early 20th century, such as C&H sugar, Standard Oil of California, Union Oil, Redwood Manufacturers and Hercules powder. By 1920 its various docks carried over half the tonnage on the Bay, principally in petroleum. Edged out by Alameda county in the 1920s in value of output, Contra Costa did much better than its Bay Area rivals in the Depression and was by 1940 the second county in the state in value of industrial output.(45)

Contra Costa developed a peculiar urban-industrial landscape owing to the nature of its industries: a series of worker villages and company towns (Figure 7). While some factories employed hundreds of workers, almost all were capital intensive, high throughput operations that generated less total employment than the myriad workshops of Oakland and San Francisco (Figure 1). The most extreme form of this occurred at the several powder works, which favored Chinese men living in bunkhouses because of frequent explosions. Such places as Hercules, Rodeo, and Cowell were little more than company towns. Crockett, the third largest settlement in the county, was settled mostly by sugar workers. Pittsburgh, the second largest, was mostly a steel town. Only Richmond, at the western end of the industrial belt and the terminus of the Santa Fe Railroad (1899), became a small city, counting 80 factories and 23,000 people by 1940. Contra Costa county’s population came to only 32,000 in 1910 and a rather modest 99,000 by 1940 — in sharp contrast to the rampant urbanization in Alameda county.(46)

Figure 7: Map of Contra Costa industrial belt, 1915

The first manufactures to come to Contra Costa county were powder and dynamite works serving the mining industry. Atlas Powder and California Power Works moved out from San Francisco circa 1880, and were joined by a half dozen others thereafter. These were leftovers from the mining era, who were fleeing from nuisances complaints in the city. But a new industrial age was dawning, and it soon made its mark in Contra Costa. Chemical plants entered the picture at the turn of the century, as demand for sulphuric acid, chlorine and ammonia fertilizers increased with advances in chemistry and industrial agriculture. Peyton Chemical was first, in 1898, followed by Stauffer Chemical in Stege (Richmond), Great Western Electro-Chemical, and others. Then came the oil refineries, another index of the new industrial era. A band of oil refineries along the river would make the Bay Area one of the chief refining centers in the United States. The first big refinery was Union Oil in 1896; Standard Oil followed at Richmond in 1901, and four others came in soon thereafter. Oil came by pipeline, ship and tank-car from the San Joaquin and Ventura fields.(47)

Another major industry was foodstuffs. In the 19th century, the wheat boom had given birth to Port Costa, a rump town fronted by miles of docks for transhipment from rail to ship; the biggest warehouses went up circa 1880. But Port Costa and wheat went into sharp decline in the 1890s, when Contra Costa county was just catching fire. The fish packing industry started early, too, but had more staying power. The great California fish packing industry (famous from Monterey’s Cannery Row) began along the Sacramento river: the first cannery to open was FE Booth in 1875, three more plants were there by the early 1880s, and 17 still survived in 1940. A whaling station and rendering plant operated for many years at Point San Pablo (Richmond). California & Hawaiian (C&H) built an immense sugar mill at Carquinez Straits at the turn of the century, while the crenellated fortress of Winehaven, built by the California Wine Association at Point Molate (Richmond), was the biggest winery in the world before Prohibition closed it down.(48)

Primary metals were another mainstay of Contra Costa industry. Selby’s lead smelter and shot works (later ASARCO) moved from San Francisco to the Carquinez Straits in 1884, adding gold and silver smelting and a cartridge factory later. Copper smelting was first tried in 1864, but the most impressive operation came in the twentieth century with Mountain Copper (Mococo) at Bulls Head Point (Martinez). Steel came to the county in 1908 when Columbia Steel (later US Steel) chose a site upriver at Pittsburg. Also significant in the Contra Costa industrial complex were wood, paper and building materials. Building materials went through a major restructuring around the turn of the century, with the introduction of portland cement, better quality sawmills in the forests, and large-scale use of asbestos, and these technological changes featured in the shift of industry to Contra Costa: the Redwood Manufacturing Company’s lumber mill, Cowell’s cement plant, Johns Manville’s asbestos works, and California paper and cardboard mill.

San Francisco capitalists dominated the development of Contra Costa county, which was more an industrial colony than Oakland. Almost all the county’s major factories were dreamed up and financed from the city, including Selby, Great Western Electro-Chemical, and Redwood Manufacturing Company. San Francisco financiers orchestrated the rail, water, oil and electricity networks that fed the new industrial district, including the crucial link to the Santa Fe that broke the Southern Pacific’s rail monopoly into the Bay Area. The county’s largest city, Richmond, was almost entirely a creature of San Francisco designs: Standard Oil of California was city based, plant manager William Rheem organized the local trolley line to tie Richmond to the rest of the East Bay, HC Cutting put together the company that developed the inner harbor, and Fred Parr came in to build the outer harbor terminals and to negotiate Ford’s move from San Francisco to Richmond. Other Richmond enterprises, such as Stauffer, Winehaven and Atlas, were funded by San Francisco investors. Oakland capital was represented by John Nicholl, who owned most of Point Richmond where the Santa Fe terminus and railyards were located.

Several upriver towns were also founded by city capitalists: Port Costa was the brainchild of merchant Isaac Friedlander, Pittsburg was engineered by Columbia Steel, and Crockett grew up under the aegis of C&H Sugar. Pullman's Richmond sleeping car works was one of the few outside corporations to come into the area. San Francisco's business leaders had a clear regional perspective and strategy for industrial decentralization. And they dominated the scene, given the paucity of local capital, unions or working class voters. There was little fractiousness from Contra Costa — unlike Oakland or even little Vallejo, just across the river in Solano county, which helped sink San Francisco's bid to be the home port for the Navy’s Pacific Fleet. Contra Costa county was a South City or Emeryville writ large — a clean slate on which big capital could write its industrial narrative unimpeded.(49)

Return to Part One on San Francisco

Notes

34. The chief source on industrial Oakland, including locations, is E. Hinkel and W. McCann (eds), Oakland, 1852-1938 (Oakland 1939) chapter 12. Also, The Illustrated Directory Company, The Illustrated Directory Of Oakland, California (Oakland 1896); Anonymous, Greater Oakland, 1911 (Oakland 1911); Oakland Central National Bank, Oakland, California: The City Of Diversified Industry (Oakland 1920); Oakland Tribune Year Book (Oakland 1926, 1927); R. Cleland and O. Hardy, March of Industry (Los Angeles 1929); Oakland Chamber of Commerce, Industrial Facts about Oakland and Alameda County, California (Oakland 1931); Emeryville Industries Association, Emeryville, California: Facts and Factories (Emeryville 1935), Emeryville Industries Association, A Roster of Emeryville Industries (Emeryville, c1936) .

35. Carpentier owned the waterfront from 1852 to 1868, then ceded it to the Oakland Waterfront Company, held by himself, his brother and Samuel Merritt, as well as Leland Stanford and other San Francisco barons. J. Dykstra, A History Of The Physical Development Of The City Of Oakland: The Formative Years, 1850-1930 (Unpubl. M.A. thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 1967); B. Bagwell, Oakland: Story Of A City (Novato 1982) .

36. Calkins & Hoadley op.cit. 217, 156 & 212. Hinkel and McCann op.cit. call Oakland “the Glasgow of the US, the Marseilles of the Pacific and the Detroit of the West”, boosterist terms promoted by local business leaders in the preceding years. Published figures can be misleading because much of East Bay industry was in unincorporated areas or because of exaggeration by Chamber of Commerce type sources.

37. US Bureau of Census, Census of Manufactures, 1914, I, 179. There were seventeen CalPak canneries in the south county alone. Oakland Chamber of Commerce, op.cit. 22. On Bay Area canning see J. Cardellino, "Industrial location: a case study of the California fruit and vegetable canning industry, 1860 to 1984" (Unpubl. M.A. thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 1984); W. Braznell, California’s Finest: The History Of Del Monte Corporation And The Del Monte Brand (San Francisco 1982); Hackett op.cit.; Hinkel & McCann op.cit.; Calkins & Hoadley op.cit.

38. Hinkel & McCann op.cit.; Emeryville Industries Association op.cit.. Overall, California’s steel and machinery industries made spectacular advances in the 1910s, due in part to low-cost energy and Federal wartime spending. Gordon op.cit. 56.

39. Hinkel & McCann op.cit. J. Moore, The Story of Moore Dry Dock Company: A Picture History (Sausalito, 1994) .

40. Hinkel & McCann op.cit.; Oakland Tribune Year Book 1926 53, 181; H. Christman, "Development of the pacific coast automotive industry" Western Machinery World January (1929) 13-19.

41. On the residential expansion of Oakland, see Dykstra op.cit. and Bagwell op.cit. On local real estate cycles, see L. Maverick, Cycles in real estate activity Journal of Land and Public Utility Economics 8 (1932) 191-99. The Realty Syndicate was responsible for about half of modern Oakland, especially along the foothills, where middle class riders used the trolleys to commute from homes in the elite districts such as Claremont, Elmwood, Piedmont and Trestle Glen. See also Walker, "Landscape and city life".

42. Emeryville Industries Association op.cit.. Emeryville’s political history has not been adequately told. Emeryville preceded the first industrial suburb of Los Angeles, Vernon, by eight years. On Berkeley zoning, see M. Weiss, Urban land developers and the origins of zoning laws: the case of Berkeley Berkeley Planning Journal. 3 (1986) 7-25.

43. Vance op.cit. emphasizes Oakland’s independence. On the port, see Bagwell, op.cit.; Dykstra, op.cit. On labor and Oakland politics, see C. Rhomberg, Social Movements In A Fragmented Society: Ethnic, Class And Racial Mobilization In Oakland, California, 1920-1970, Unpubl. PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley 1997. Oakland’s Chamber of Commerce could brag in 1931 that the city was 90% Open Shop. Oakland Chamber of Commerce Industrial Bureau op.cit., 11. On Knowland, see G. Montgomery and J. Johnson, One Step From the White House: The Rise and Fall of Senator William F. Knowland (Berkeley 1998); E. Cray, Chief Justice: A Biography of Earl Warren (New York 1997). On Kaiser, see M. Foster, Henry J. Kaiser: Builder in the Modern American West (Austin 1989). On the Greater Oakland movement, see R. Self, Shifting Ground In Metropolitan America: Class, Race, And Power In Oakland And The East Bay, 1945-1977 (unpubl PhD diss, Stanford, 1998) .

44. On metropolitan consolidation, see M. Scott op.cit, 134 and Anonymous, The Bay Basin and Greater San Francisco, Merchants’ Association Review, December 1907, Anonymous, Greater San Francisco Edition, San Francisco Chronicle, December 22, 1907. Scott emphasizes the failure to unify the region and its costs; for a contending view, see R. Lotchin, "The Darwinian city: the politics of urbanization in San Francisco between the world wars" Pacific Historical Review 48 (1979) 357-81.

45. For a comprehensive history of local industry, see M. Purcell, History of Contra Costa County (Berkeley 1940) chapters 24 and 25; also J. Whitnah, The Story of Contra Costa County, California (Martinez? 1936); G. Emanuels California’s Contra Costa County (Fresno 1986); and promotional pamphlets from 1887, 1903, 1909 and 1915 held in the Bancroft Library, e.g. Board of Supervisors, Contra Costa County: Leading County Of The West In Manufacturing (Martinez c 1915). Figures on output from Census of Manfacturers, various years. Shipping figures, Calkins & Hoadley op.cit. 158.

46. Figures from Purcell op.cit.; Emanuels, op.cit. Company towns were segregated by race and ethnicity, as at Tormey/Selby, Valona/Crockett, or Hercules. On Richmond, see J. Whitnah, A History of Richmond, California (Richmond 1944); E. Davis, Commercial Encyclopedia Of The Pacific Southwest (Berkeley 1910-15).

47. Oil and electricity fueled Contra Costa’s industrialization. The first oil pipeline, from Bakersfield, arrived in 1903. Meanwhile, thanks to the water resources of the Sierra, use of electricity in California manufacturing outran the rest of US by six times in 1904, triple in 1909 and double in 1919. Gordon, op.cit. 99. On electrification, see J. Williams, Electricity And The Making Of Modern California (Akron 1997).

48. On fish canning, see A. McEvoy, The Fisherman's Problem: Ecology And Law In The California Fisheries, 1850-1980 (New York 1986); K. Davis, Sardine Oil on Troubled Waters (Unpublished PhD thesis, Berkeley, 2002) .

49. Investors from Issel & Cherny op.cit. Chapter 2. There were few upstart capitalists in Contra Costa’s history. On Vallejo versus San Francisco, see R. Lotchin, Fortress California, 1910-1961: From Warfare To Welfare (New York 1992) .