Nob Hill and Pacific Heights at Turn of 20th Century

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

Looking up Nob Hill on Powell Street from Sutter at the bottom in 1895.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

1978 view looking up Nob Hill on Powell Street; Sutter at the bottom.

Photo: David Green

As one travels north on Fillmore Street through the Western Addition, the terrain begins to rise at about California Street. The higher one goes physically, the higher the income levels. Pacific Heights, an upper-class residential district, was technically a part of the Western Addition, but it differed significantly from most of the area. Stretching westward between California and Union, from Van Ness to Presidio, Pacific Heights continued the patterns established atop Nob Hill in the 1870s, and Nob Hill—Pacific Heights may be considered as one major division of the city, an elite district perched on high ground, there to see and to be seen.

The heights to the north and west of the central business district had long attracted the city’s commercial and financial elite. South Park, the elite neighborhood of the 1850s, in the heart of South of Market, soon was overwhelmed by the surrounding industrial area, especially after a massive effort reduced a high hill barring Second Street from continuing to Townsend. Thereupon, the city’s elite migrated to the lower slopes of what was then called the California Street Hill, soon to become Nob Hill. With the development of the cable car, construction on Nob Hill was no longer limited to the lower slopes.(28)

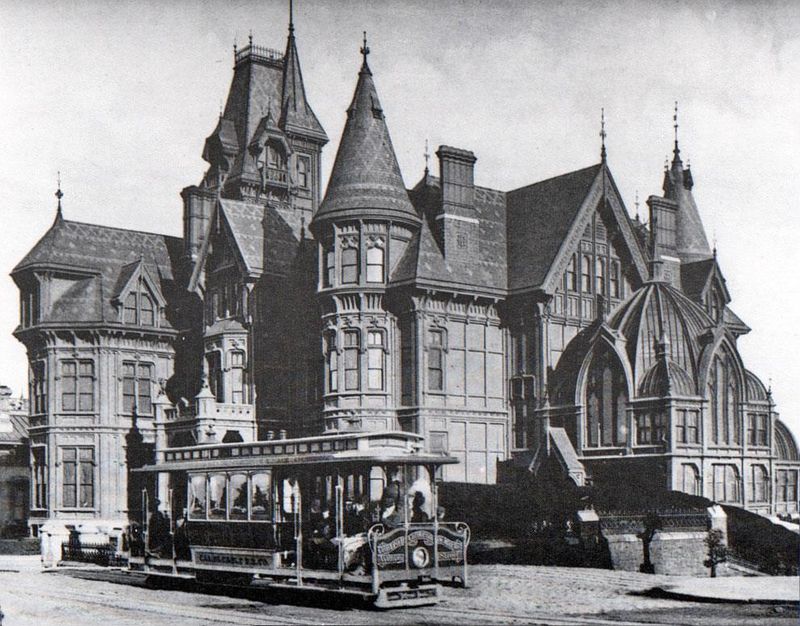

The original Mark Hopkins mansion, seen here in 1895, that the Hotel was built over after its destruction in the 1906 earthquake and fire.

Photo: courtesy Roger Rubin via Facebook

In the 1870s, the top of the hill saw the construction of elaborate—some would say bizarre—mansions by some of the wealthiest and most powerful families in the West. Charles Crocker, one of the Big Four of the Southern Pacific Railroad, built his home where Grace Cathedral now stands. Ambrose Bierce, a journalist, said of this house: “There are uglier buildings in America than the Crocker home on Nob Hill, but they were built with public money for a public purpose; among the architectural triumphs of private fortune and personal taste it is peerless.” Next to Crocker’s house, across Taylor Street to the east, was the more modest (and some would say more tasteful) home of David Colton, chief counsel for the Southern Pacific; Colton’s home was later purchased, but seldom used, by Collis Huntington, another of the Big Four. Next, across Yerba Buena Street to the east, was the town house of James Flood, one of the Silver Kings, masters of the Comstock Lode. Diagonally across the street on the corner of Mason and California was the home of another of the Big Four, Mark Hopkins, a house that Gertrude Atherton once said “looked as if several architects had been employed, and they had fought one another to a finish.” Next to the Hopkins house was the home of Leland Stanford, the final member of the Big Four, president of the Southern Pacific until 1890.(29)

On the corner of Taylor and Sacramento streets, a block north of the Crocker house, was the residence of George Hearst, mining millionaire. Directly across the street from the Crockers were the Tobins, of the Hibernia Bank. A block south and west was Theresa Fair, divorced wife of James Fair, another of the Silver Kings. Others on the hill included William Coleman of Vigilance Committee fame; James Haggin, a partner of Hearst; and Haggin’s brother-in-law and partner Lloyd Tevis. Crocker’s house may well have been the most exuberant in its architectural pretentiousness, but the Flood mansion was the most ostentatious, constructed at a cost of $1.5 million, built of brownstone brought from Connecticut, surrounded by a $30,000 bronze fence requiring the full-time attention of one servant just to keep it polished. As the San Francisco Junior League put it in their survey of the city’s architecture published in 1968: “The Nob Hill householders of the 1880s and 1890s were not the sole proprietors of the State of California—but they may well have represented the majority interest.”(30)

2550 Webster Street in Pacific Heights, the William Bourn mansion, built in 1896, San Francisco Landmark #38.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Houses in the Pacific Heights area west of Nob Hill could not be seen so readily from afar, but their residents included millionaire merchants and manufacturers, mining and shipping magnates, and others of great wealth and power. There lived Michael H. de Young of the San Francisco Chronicle; William Bourn of the Spring Valley Water Company; William Whittier, partner in the largest paint company on the West Coast; and various descendants of Charles Crocker, James Flood, and Claus Spreckels. Well over a third of the families listed in Our Society Blue Book, a listing of “people of social standing and the highest respectability," were on or near Pacific Heights in 1902. After 1906, fewer new mansions were built in the city by the most wealthy, who typically maintained country homes down the peninsula in Belmont or Burlingame, or north in Marin County, or across the bay. Some of the Pacific Heights homes, in fact, served as town houses for families who lived outside the city, just as Flood built his Nob Hill mansion as a townhouse, complementing his Menlo Park country home. Scattered through Pacific Heights were entire blocks of more modest homes, similar to those of the Western Addition, built and occupied by upper-middle-class merchants like those of the Western Addition. The Pacific Heights area in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had abundant civic amenities, boasting more parks than in all of the Mission District. Streetcar lines ran on nearly all the major east-west thoroughfares of the area, providing easy movement from home to the central business district.(31)

Notes

28. Shumate, A Visit to Rincon Hill: Averbach, “South of Market,” pp. 199–200.

29. Delehanty, Walks and Tours, pp. 176-178; Olmsted and Watkins, Here Today, pp. 66–69; Lewis, Silver Kings, pp. 232–233; Ambrose Bierce, The Ambrose Bierce Satanic Reader, quoted in John Van der Zee and Boyd Jacobson, The Imagined City: San Francisco in the Minds of Its Writers (San Francisco, 1980), p. 23 ; Altrocchi, Spectacular San Franciscans, pp. 173–176, 180; Gertrude Atherton, My San Francisco: A Wayward Biography (Indianapolis, 1946), pp. 32–37, esp. pp. 32–33.

30. Altrocchi, Spectacular San Franciscans, pp. 170–171; Atherton, My San Francisco, pp. 31–32, 37—39; Olmsted and Watkins, Here Today, p. 66. Flood’s mansion was the only one to survive the fire in 1906; it now houses the city’s most prestigious club, the Pacific Union.

31. Delehanty, Walks and Tours, pp. 132–148; Olmsted and Watkins, Here Today, pp. 14-39; Narell, Our City, p. 167; Hoag, ed., Our Society Blue Book: 1902, pp. 149–196. Just under a third of the Blue Book families were in the Western Addition, about 10 percent were in the Nob Hill area, nearly 10 percent were elsewhere in Downtown, just under 10 percent were in the Mission District, and about 1 percent each were South of Market or in North Beach.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 3 “Life and Work”