India Basin and the Southeast Bayshore

Historical Essay

by Pete Holloran

India Basin during World War II. August 23, 1943 view southeast from top of power plant.

Photo: OpenSFhistory wnp14.13007

India Basin Nov 7, 1944.

Photo: OpenSFhistory wnp14.12665

During the spring of 1998 I wandered through the derelict lands of Pier 98, a twenty-five acre peninsula that juts out into the bay under the imposing shadow of the massive PG&E Hunters Point Power Plant at the end of Evans Avenue. Among the acres of pampas grass and yellow star-thistle I found a small patch of native wildflowers that are otherwise rare in San Francisco. In the middle of what most would perceive as an industrial wasteland, how did these ever survive?

The call of a Killdeer interrupted such thoughts, reminding me that birds have a more discerning eye. They recognize the resilience of nature, the persistence of natural processes. Storm waves erode the edges of the bay fill and plant fragments and seeds float in with the tides to convert abandoned landfill back to bay lands. Tidal marshes formed in this way are a shadow of their former selves, but they provide habitat just the same to hungry shorebirds or mating Killdeer. In the waters and upland edges of India Basin at least 118 bird species have been seen; 21 species, including American Avocet and Killdeer, are confirmed nesters (Hopkins 1996).

View from top of Albion Castle northward across India Basin as rainbow appears on a rainy day in 2010.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Back to the ecological mystery: how did the rare wildflowers blossom forth from a weedy landfill? It is likely that they came in with the fill itself, in this case serpentine rock and soil brought in from nearby Hunters Point or Potrero Hill. The native goldfields, lupine, and clovers had persisted here ever since the fill was first placed in the mid-1970s. As weeds and motor bikes invaded the site they may have steadily lost habitat, finding refuge only in the harshest serpentine soils that kept most weeds from invading. During the El Niño winter of 1998 they burst forth. Only the bees, searching for pollen, knew that their siblings were miles away in the serpentine slopes of Hunters Point and Potrero Hill.

When the Port of San Francisco first proposed a 48-acre bay fill project in the late 1960s, it planned to place clean sand and dredged bay mud on the site instead of serpentine rock and wood debris. They received a permit in 1970 from the Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) to begin filling the subtidal bay lands by pointing to the economic benefits. The project, known as Pier 98, was meant to serve container ships and anchor the western end of a proposed Southern Bay Bridge. By 1977, when the Port aborted the project and halted construction of the pier, container ships had mostly deserted San Francisco for Oakland and the Southern Crossing was dead.

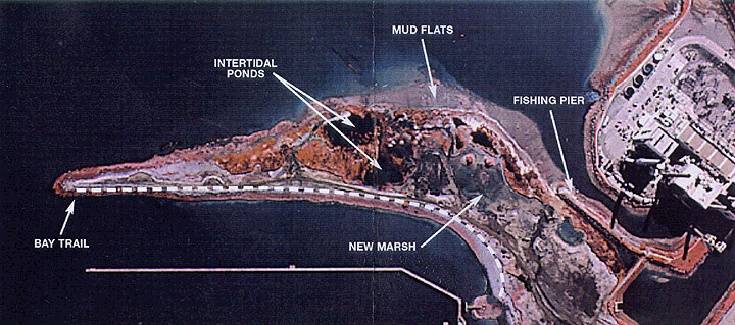

In the fifteen years it took for the BCDC and the Port to resolve their differences about the legality of the bay fill, Pier 98 became a valuable recreational resource for the citizens of Hunters Point and the Bayview district. It also became habitat as storm waves and tidal action eroded the fill along the southern edge. A complex of tidal wetlands and intertidal ponds developed; after decades of absence, marsh plants could once again be found in San Francisco.

The new Heron's Head Park at Pier 98 in San Francisco.

Heron's Head Park (strip in bay) and India Basin Park (green area in foreground), December 2012.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Aerial of Heron's Head Park in 1999 before it was formally parkland. PG&E power plant just to the lower right of Heron's Head in this photo.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

In its agreement with BCDC, the Port agreed to expand the tidal marsh, cap sections of the site that had received illegal fill (wood material, construction debris, etc.), and provide more amenities for recreational users. In 1999 the wetlands were expanded to 9 acres in a partnership between the Port, City College, local schools, and the San Francisco League of Urban Gardeners. It was christened Heron's Head by someone who noticed its resemblance in aerial photos to the Great Blue Heron that are commonly seen in the area.

Sitting at end of Heron's Head Park facing Hunter's Point, 2007

Photo: Francesca Manning

Tidal inundation and erosion have created other tidal marshes in fill along the edge of derelict industrial lands at Pier 94, Yosemite Channel, and elsewhere along the shoreline of Hunters Point. In the future the city may provide additional recreational opportunities and expand tidal marshes along the southeast bayshore.

Wetland restoration in Yosemite Slough, December 2012, looking southeast from north shore.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

References:

Levine-Fricke-Recon. 1997. Alternatives analysis report, Pier 98, Wetlands and Open Space Project. Prepared for the Port of San Francisco.

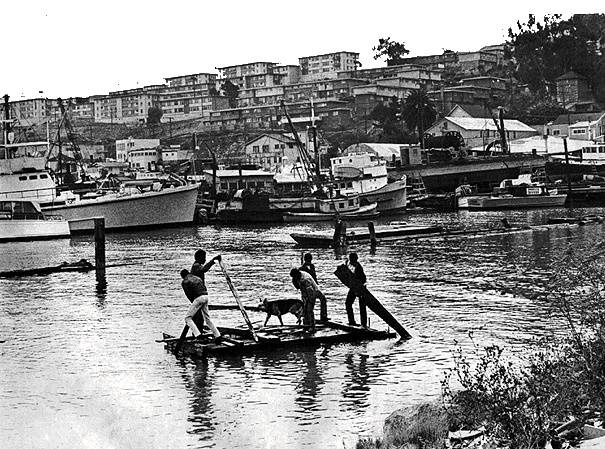

India Basin c. 1969.