Corwin Community Garden and Seward Mini-Park

Primary Source

Corwin Street Community Garden sign.

California buckeyes line the path in the native plant garden.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Buckeye, June 11, 2005.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

How was the Land Saved?

Corwin Street and Seward Street are lined with houses and apartments. What makes this lot any different? The answer is a ten-year struggle by dedicated neighbors, a struggle which changed the course of development in the whole city.

In 1963, this neighborhood was full of young families with children, the "baby boom" in full swing. Housing was rapidly being built to accommodate this growth, and empty lots were quickly being turned into apartment dwellings. Soon, only one space remained connecting Seward Street and Corwin Street. It wouldn't last for long, though: a 105-unit building was planned to stretch all the way from Corwin Street down to a garage entrance on Seward Street (including the sites of both the current garden and mini-park).

Three years of struggle ensued. Fearing loss of crucial open space, residents and Eureka Valley neighbors began a campaign of petitions and letters to city, state and federal officials, followed by years of public hearings, Planning Commission battles, Board of Permit Appeals meetings and audiences with the mayor. Along with dedicated residents too numerous to mention, B. Shamon Schwarzschild, the Seward Street Mini-Park Committee, and the Eureka Valley Promotion Associat5ion were instrumental in this effort.

It all came to a head on January 12, 1966, the last day for the developer to begin work before expiration of the permit. As the bulldozers arrived to begin work, neighbors started a sit-in on this site, forcing developers to abandon their plans.

The outcome of this struggle permanently changed development in the City and led to legislation requiring a minimum amount of neighborhood open space.

Open Space: Now What?

On March 6, 1966, residents gathered to celebrate their victory and begin the next round: an effort to turn the newly-saved open space into an asset for the whole community, this time campaigning for the Department of Recreation and Parks to locate a proposed Eureka Valley mini-park on the site. Again, after years of letter writing and petitioning, and after having garnered the support of Mayor Joe Alioto, the Board of Supervisors, and Senator George Moscone, the Eureka Valley Mini-Park Task Force successfully negotiated the local and federal bureaucracy.

From Vacant Lot to Native Plant Garden

The Seward Street Mini-Park has drawn children (and adults!) to its slide for nearly thirty years. The upper part of the land, though, remained a weed-choked vacant lot until quite recently, when a new generation decided to take matters in hand. In the summer of 1995, area residents held a community meeting and decided that a showcase for California's diverse plant life would be more appropriate on this steep hillside than having individually-gardened plots. That fall, with the help of the San Francisco League of Urban Gardeners (SLUG) and several very dedicated City staff, they began the task of creating the California native plant garden at the upper end of this community treasure. At seven years old, the garden is really coming into its own.

We pay tribute to all those whose efforts saved this hillside, helped build Seward Street Mini-Park, and nurtured the Corwin Street Community Garden. Thank you for proving that individuals working together can make a profound difference.

--from the sign at the top of the Community Garden

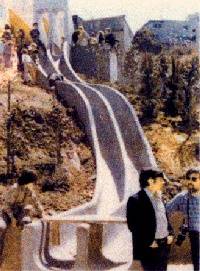

The famous cement slide in Seward Street Mini-Park in the 2000s.

Seward Street Mini-Park on opening day, May 21, 1973.

The slides in the 1990s.

Photo: SearchingSanFrancisco

The concrete slides were designed by a 14-year-old girl named Kim Clark who lived on Seward Street and won a "Design the Park" competition that was put on by artist Ruth Asawa. The slides were said to be inspired by one from Playland at the Beach which closed down in 1972.

Garden shot featuring cactus from wider west, July 2008.

Photos: Chris Carlsson