California Fur Rush

Historical Essay

By Sohyun Im, October 2013

Four sea otters cavort in Pacific Ocean kelp forest in Morro Bay, California, 2007. The sea otter was thought to have been hunted to extinction during the early 1800s for nearly a century before a colony was discovered off the coast of Big Sur in the 1940s.

Photo: "Mike" Michael L. Baird, wikimedia commons

The 1849 Gold Rush might have turned California into the land of opportunity. However, a few decades before the California Gold Rush, the much less remembered California Fur Rush began. Before 1825, American, English, Spanish, French and Russian fur hunters were drawn to the northern and central California coast to harvest mammals with valuable furs, including sea otter, fur seal, beaver, river otter, marten, fisher, mink, fox, weasel, and harbor seal. The San Francisco Bay Area, the center of the early fur trade operations, provided many of these species as well as the lesser animal species such as raccoon, badger, and skunk. California’s early fur trade opened up a new era of world trade in the American West, particularly the Bay Area.

The history of the fur trade traces back to Danish captain Vitus Jonassen Bering’s expedition in 1741. Bering and his crew suffered a shipwreck on the Commander Islands in the Russian far east. They discovered the sea otters that they hunted for survival were extremely valuable and took 900 sea otter pelts to Russia. Many of the pelts were sold to the Chinese who used them to make belts, capes, and clothes for the wealthy class of people. (Joy)

In 1778, Captain James Cook and his men obtained otter skins at Nootka Sound on the Northwest Coast of Vancouver Island. Although Cook was killed on the way to China, his men sold the skins to the Chinese with a profit of 1,800%. (Bockstoce 1) After hearing that an enormous fortune could be made selling otter skins to China, New England began sending American ships to hunt sea mammals on the Pacific coast. The California fur trade had begun by 1785, ten years after Juan de Ayala sailed the first ship through the Golden Gate in 1775. (Grinnell)

The first trade began as early as 1784 when a Spanish expedition headed by Señor Vincente Vasadre y Vega traded abalone shells, beads, and various metal articles to the Indians for sea otter pelts. Senor Vega organized and expanded the sea otter trade. The furs obtained were sent to Mexico for tanning and then to China in exchange for quicksilver, which was urgently needed in the Mexican mines. From 1786 to 1790, 9,729 sea otter pelts and an unknown number of seal skins were shipped to Manila.

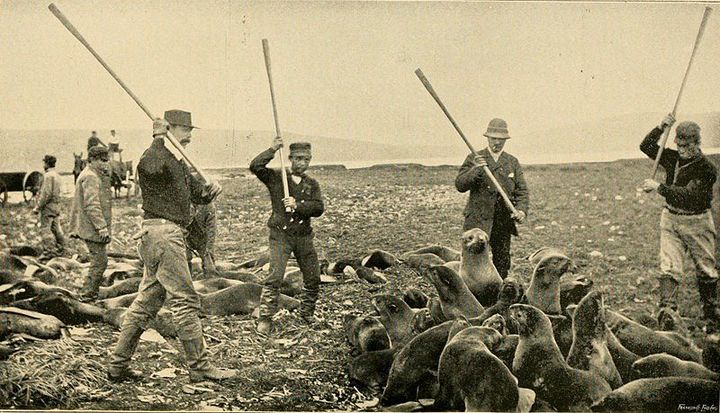

Killing fur seals on St. Paul Island, Alaska, 1890s.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

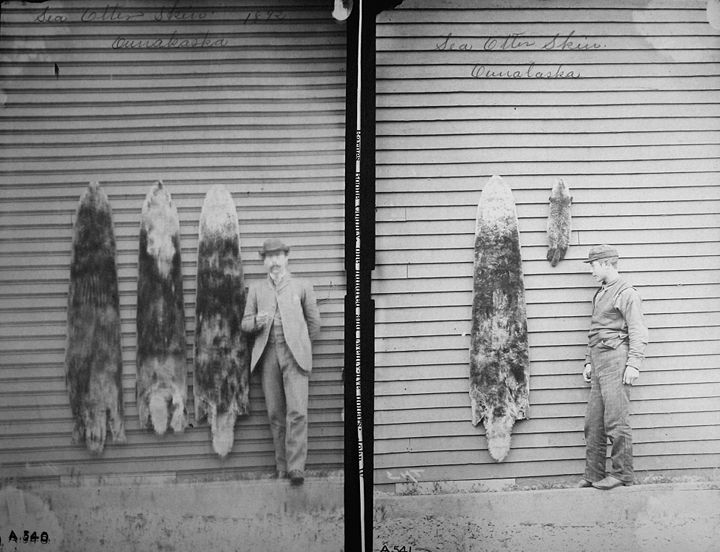

In 1786, France sent Conte de La Perouse to investigate the fur trade possibilities. Between Alaska and California, he obtained about a thousand sea otter pelts, which he sold in China for $10,000. Between 1727 and 1742, single sea otter pelts from the Asiatic Pacific sold for $80 to $100 in China where it was treated as the royal fur. Between 1775 and 1777, England sold 29,932 pelts to Russia for $90 to $100 each. After that the price declined until the middle 19th century when the prices increased due to growing scarcity. (Skinner)

From 1803 to 1805 over 17,000 sea otter pelts were taken in California waters. The Russian-American Fur Company hunted all the way from Trinidad Bay in Humboldt County to Baja California. During 35 years, the company took over 100,000 pelts in California. (Joy) Bostonian ships dominated the fur trade between California and China through the 1820s, when the California sea otter almost entirely disappeared due to overhunting and lack of concern for the future of the sea mammals. (Caughey 195)

The companies and ships expanded their business by hunting fur seals. Hunters were drawn to the Farallon Islands for sealing. From 1812 to 1840, the Russians had a sealing station in the islands, hunting approximately 1,500 fur seals annually. (Thompson) In 1810, American ships hunted together with the Russians, taking 30,000 seal skins. (Bancroft) By 1822, the Russians discontinued sealing for two years and only 1,200 fur seals were taken annually in the Farallon Islands. (Khlebnikov) Eventually, within the next few years, the seal disappeared from the islands. In 1841, the Russians left their base, Fort Ross. (White)

The decline of the oceanic fur industry in the Far West resulted in the growth of an inland fur industry. In 1840, explorer Captain Thomas Farnham discovered that beavers were very abundant near the mouths of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers. (Farnham) The Hudson’s Bay Company, a British-owned commercial corporation specialized in trading fur, took 4,000 beaver skins on the shores of San Francisco Bay and sold them for 4 dollars each. Numerous beavers were continuously found in Alameda Creek in the East Bay, Coyote Creek in Santa Clara County, Sonoma Creek, Russian River and the Napa River. (Skinner) During the 1830s to 1840s, the Americans extirpated almost the entire population of beaver very rapidly in the coastal areas north of San Francisco, just like it happened to sea otters and fur seals. The brief heyday of the western fur trade drew to a close.

From the 1790s to the War of 1812, there were no powerful monopolies in the American fur trading industry. The trade was handled by a number of small merchants who were not involved in the actual hunting. Competition was fairly open. Annual exports were over $800,000 during 1804 to 1807, the peak years. However, the exports fell when large and powerful corporations took over the fur industry during the 1820s to 1830s. Large companies and monopolistic practices tended to retard rather than expand production. (Clayton, 218) Monopolistic companies accelerated extirpation of fur animals and finally their reckless hunting led them to close their businesses.

From the beginning to the end of the California Fur Rush, the San Francisco Bay Area was the center of the fur trade industry in the Far West. The main reason was that the Bay Area provided perfect places for harvesting many valuable animals, and the bay’s geographic location enabled the fur traders to ship the products easily to the countries of destination. Most of the fur products were taken to China, Russia, and other Pacific coastal regions where the climate created high demand.

The geographical range and scale of the fur trade was very large, as described so far. The Fur Rush in the San Francisco Bay Area stimulated the economy of California before the Bay Area became internationally and nationally recognized as an important region. As the Bay was the center of the fur trade, many businessmen and private companies on the East Coast invested in the California fur business by sending people to the Far West in order to make a fortune. Not only Americans and Canadians were interested in the fur business. The Europeans played important roles also.

Sea otter skins, 1892.

Image: Wikimedia commons

It was the Russians who had the best hunting skills to catch sea otters and introduced the hunting techniques to the Americans. Many Russians who worked in the fur industry settled on San Francisco and the naming of San Francisco’s Russian Hill neighborhood is attributed to the remains of Russian fur traders and sailors buried there. The British companies entered and took large portion of the industry. Of course, it may be fairly said that there would not have been the “Fur Rush” if the Chinese did not buy the fur from the Westerners, as the Chinese had a very high demand all the time. Some scholars claim that the fur trade can be tied to an imperial struggle for power; the fur trade served both as an incentive for expanding and as a method for maintaining dominance. This suggestion might be the reason why so many people from various lands were avid to join and expand the fur business.

In 1911, the United States, Great Britain, and Russia signed the Northern Fur Seal Treaty that ended the reckless hunting of marine mammals, especially sea otters and fur seals. The protection applied to California in 1913. (Joy) In 1972, President Richard Nixon signed the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) into law. MMPA prohibits the taking of marine mammals, import, export, and sale of any marine mammal or its product within the United States. Hunting, killing, capturing, or harassing any marine mammal became illegal. The number of animals overhunted in the past is increasing slowly, although oil spills and infectious diseases continue to threaten marine mammals in Coastal California.

As the fur supply ran out and the law prohibited hunting marine mammals for protection, the fur industry in California declined. Today, 80 percent of the fur clothing industry’s pelts come from animals raised on farms and the rest is from animals caught in the wild. There are some fur breeders and fur farms in the Bay Area raising minks, chinchillas, foxes, and rabbits. Fur sources have been changed as the early California fur industry produced most of the fur products from sea otters, fur seals, and beavers. Compared to the early period, the present fur business in the Bay Area is much smaller. Although the Fur Rush came to an end, the California Gold Rush followed in 1848. The early fur business established the foundation of the Bay Area’s trade system for the future economy. It was the fur that woke up the San Francisco Bay Area, which had been asleep for a long time.

Alaska Commercial Corporation and its industrialized slaughter of seals in the last half of the 19th century.

Works Cited

Bancroft, Hubert H. Albatross, Log-book of a Voyage to the Northwest Coast in the Years 1809-1812, Kept by Wm. Gale, MS in History of California: 1801-1824. San Francisco: A.L. Bancroft & Company. 1886. Print.

Bockstoce, John R. The Opening of the maritime fur trade at Bering Strait: Americans and Russians meet the Kanhigmiut in Kotzebue Sound. Volume 95, Part 1. Philadelphia: American Philosphical Society. 2005. Print.

Caughey, John W. History of the Pacific Coast. Los Angeles. Privately published by the author. 1933. Print.

Clayton, James L. The Growth and Economic Significance of the American Fur Trade, 1790-1890. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society. 1967. Print.

Farnham, Thomas J. Life, adventures, and travels in California. New York: Sheldon, Blakeman & Co. 1857. Print.

Grinnell, Joseph, et al. Fur-bearing mammals of California; their natural history, systematic status, and relations to man. Berkeley: University of Berkeley, California. 1937. Print.

Khlebnikov, Kiril T. The Khlebnikov Archive Unpublished Journal (1800-1837) and Travel Notes (1820, 1822 and 1824). University of Alaska Press. 1990. Print.

Skinner, John E. A Historical Review of the Fish and Wildlife Resources of the San Francisco Bay Area. (The Mammalian Resources) Sacramento: California Department of Fish and Game. 1962. Print.

Thompson, R. A. The Russian Settlement in California Known as Fort Ross, Founded 1812…Abandoned 1841: Why They Came and Why They Left. Santa Rosa: Sonoma Democrat Publishing Company. 1896. Print.

White, Peter. The Farallon Island: Sentinels of the Golden Gate. San Francisco: Scottwall Associates. 1995. Print.